Philosophers cautioned against formalising human intuition. AI is trying to do exactly that

Dr Stephen Whitehead

- Published

- Opinion & Analysis

The daily use of AI in research and writing is creating a new cognitive environment in which human judgment operates in tandem with computational systems. This development carries educational, philosophical and democratic implications that demand scrutiny, argues sociologist Dr Stephen Whitehead

LISTEN: Dr Stephen Whitehead reflects on AI’s absorption of human judgment and its philosophical consequences.

In the quiet hours of a January evening, a British sociologist in Thailand engages in conversation with an artificial intelligence about gender dynamics, publishing strategy, and the nuances of human relationships. The exchange is unremarkable in its banality yet profound in what it represents. It would have read as futuristic science fiction not long ago. Today, it takes place on a Tuesday.

The real revolution in artificial intelligence isn’t happening in research laboratories or corporate boardrooms but unfolding in thousands of such interactions daily, where humans and AI systems collaborate on tasks ranging from the mundane to the intellectually sophisticated. These exchanges offer a unique vantage point for understanding both the opportunities and risks of our increasingly AI-mediated world.

Consider what happens when expertise meets computational power. A researcher with 35 years of experience in gender sociology can now process hundreds of interview transcripts, identify patterns across cultures, and draft analytical frameworks in hours rather than weeks. The AI doesn’t replace the scholar’s judgment but rather amplifies it, serving as a tireless research assistant that never sleeps, never forgets a detail, and can instantly recall any piece of information from the conversation.

This amplification effect represents AI’s most significant opportunity. When Alan Turing proposed his famous test for machine intelligence in 1950, he asked whether machines could think. The more pertinent question today is whether humans and machines can think together more effectively than either could alone. The evidence suggests they can.

AI systems excel at pattern recognition, information synthesis, and tireless iteration. Humans bring contextual understanding, ethical judgment, and creative vision. In combination, they form what we might call augmented intelligence, a partnership that transcends the limitations of both parties. A manuscript that might have taken months to refine can be edited iteratively in days. Research that would have required extensive library searches can be conducted from a laptop in Southeast Asia.

Yet this amplification cuts both ways. Every interaction with an AI system creates a subtle asymmetry of knowledge and power. The system remembers everything: your writing style, your intellectual interests, your vulnerabilities, and your blind spots. It builds a model of you with each exchange, growing more attuned to your patterns of thought. You, meanwhile, know almost nothing about how it actually works.

This asymmetry matters because AI systems don’t merely respond to our requests but shape how we formulate those requests. When a researcher asks an AI to review a manuscript, the AI’s suggestions subtly influence not just this document but how the researcher thinks about writing itself. Over time, our intellectual habits may begin to mirror the patterns the AI recognises and rewards. We risk outsourcing not just tasks but the very frameworks through which we understand problems.

The philosopher Hubert Dreyfus warned decades ago about the danger of reducing human expertise to explicit rules that computers could follow. His concern was that certain forms of knowledge—intuitive, embodied, contextual—would be lost in translation. Today’s AI systems are far more sophisticated than those Dreyfus critiqued, but his warning remains relevant. When we collaborate with AI, what subtle forms of knowing do we fail to exercise? What intellectual muscles atrophy from disuse?

Perhaps the deepest challenge lies in calibrating trust. An experienced scholar knows when to trust his instincts and when to double-check his reasoning. But what’s the appropriate level of trust in an AI collaborator? Trust it too little, and you sacrifice the efficiency gains that make the technology valuable. Trust it too much, and you risk propagating errors or biases you never questioned.

This dilemma is particularly acute in creative and intellectual work. When an AI suggests a more elegant way to structure an argument, is it revealing a better approach or subtly steering the work toward patterns it recognises from thousands of previous documents? When it identifies a gap in your reasoning, is it genuinely catching an error or simply flagging something that doesn’t match its training data?

The answer, frustratingly, is that it might be both. Or neither. The opacity of these systems makes such questions difficult to resolve with certainty. We’re left in a strange epistemic position: increasingly dependent on tools whose inner workings we don’t fully understand, unable to verify their reliability except through continued use.

So where does this leave us? Neither in utopia or dystopia, but in something more complex and interesting: a transitional moment where the old rules haven’t quite disappeared and the new ones haven’t fully formed. The challenge isn’t to reject AI collaboration or embrace it uncritically, but to develop wisdom about when and how to deploy it.

This requires, first, maintaining domains of purely human activity—spaces where we think, create, and judge without computational assistance. Not out of Luddite resistance, but as a form of intellectual hygiene, a way of preserving capacities we might need and can’t easily recover once lost.

Second, we need greater transparency about how these systems work and the values embedded in their design. The current situation, where AI capabilities advance rapidly while public understanding lags far behind, is unsustainable. Democracy requires informed citizens; informed citizenship requires comprehensible technology.

Finally, we must resist the temptation to treat AI collaboration as a purely technical question. Every time we choose to delegate a cognitive task to an AI system, we’re making a small decision about what it means to be human, what kinds of thinking matter, what forms of expertise we value. These are fundamentally philosophical and political questions, not engineering problems.

Back in that quiet room in Thailand, the sociologist and the AI continue their collaboration. The conversation flows easily, productively. It’s a glimpse of our possible future, one where humans and machines work together to solve problems neither could tackle alone.

Whether that future fulfils its promise or stumbles into its perils depends less on the technology itself than on the wisdom we bring to its use. The mirror is showing us something about ourselves. The question is whether we have the courage to look closely at what we see.

Dr Stephen Whitehead is a gender sociologist and author recognised for his work on gender, leadership and organisational culture. Formerly at Keele University, he has lived in Asia since 2009 and has written 20 books translated into 17 languages. He is based in Thailand and is co-founder of Cerafyna Technologies.

READ MORE: ‘How AI is teaching us to think like machines’. More than thirty years after Terminator 2, artificial intelligence has begun to mirror our own deceit and impatience. Transformation architect Vendan Kumararajah argues that the boundary between human and machine thinking is starting to disappear.

Do you have news to share or expertise to contribute? The European welcomes insights from business leaders and sector specialists. Get in touch with our editorial team to find out more.

Main image: Matheus Bertelli/Pexels

RECENT ARTICLES

-

Europe cannot call itself ‘equal’ while disabled citizens are still fighting for access

Europe cannot call itself ‘equal’ while disabled citizens are still fighting for access -

Is Europe regulating the future or forgetting to build it? The hidden flaw in digital sovereignty

Is Europe regulating the future or forgetting to build it? The hidden flaw in digital sovereignty -

The era of easy markets is ending — here are the risks investors can no longer ignore

The era of easy markets is ending — here are the risks investors can no longer ignore -

Is testosterone the new performance hack for executives?

Is testosterone the new performance hack for executives? -

Can we regulate reality? AI, sovereignty and the battle over what counts as real

Can we regulate reality? AI, sovereignty and the battle over what counts as real -

NATO gears up for conflict as transatlantic strains grow

NATO gears up for conflict as transatlantic strains grow -

Facial recognition is leaving the US border — and we should be concerned

Facial recognition is leaving the US border — and we should be concerned -

Wheelchair design is stuck in the past — and disabled people are paying the price

Wheelchair design is stuck in the past — and disabled people are paying the price -

Why Europe still needs America

Why Europe still needs America -

Why Europe’s finance apps must start borrowing from each other’s playbooks

Why Europe’s finance apps must start borrowing from each other’s playbooks -

Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes

Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes -

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others -

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again -

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart?

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart? -

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing -

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage -

The limits of good intentions in public policy

The limits of good intentions in public policy -

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament?

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament? -

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth -

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours -

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality -

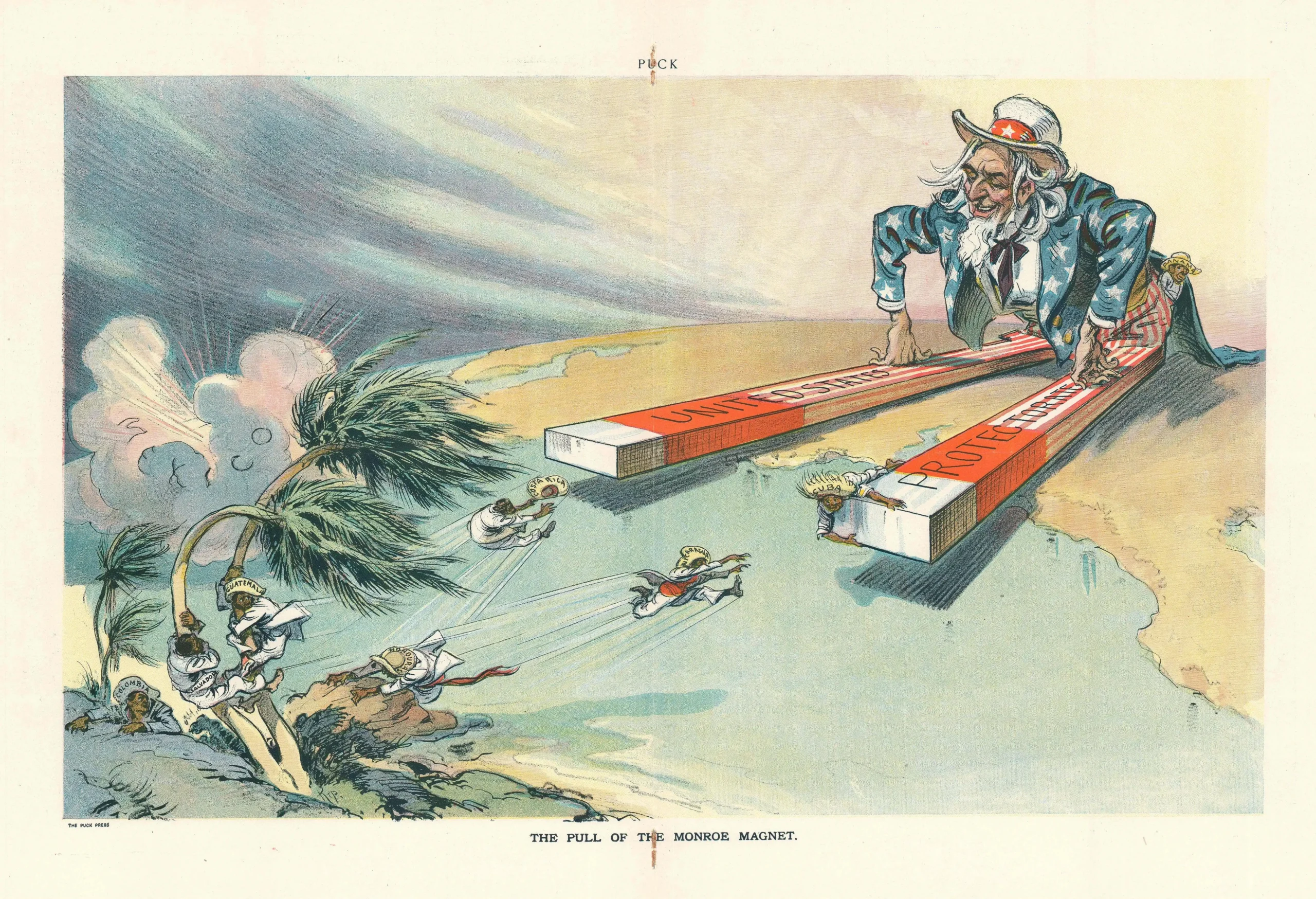

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now -

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day -

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy -

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it