The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage

Harry Margulies

- Published

- Opinion & Analysis

Tax planning provokes moral outrage far beyond its legal meaning. Harry Margulies examines how everyday, lawful decisions are recast as suspect behaviour, why legality remains the only workable standard in a free society, and how differing tax regimes create incentives that individuals and businesses are rational to follow

The fact that people plan their taxes is as natural as planning any other expenses. Yet tax planning, in particular, has become emotionally charged, and those who do plan are often shamed as “tax avoiders”, particularly by people who are not in a position to plan at all. Legal language is increasingly replaced by moral outrage, with virtue-signalling politicians eagerly hopping on the bandwagon. In the process, what is legal is blurred with what some consider immoral—even though those same politicians are the authors of the rules themselves.

An inconvenient truth is that where tax rules apply equally to everyone, if your income barely covers basic necessities, you cannot afford to plan your taxes. That is not a failure of the tax system but a consequence of inequality.

Without incomes or gains, there would be no taxes paid at all. The state takes a portion of your income, and while how it does so (and how you comply) certainly deserves scrutiny, the starting point must be legality. The fundamental question is simple: is your tax planning legal?

Before going through a few examples, we need to establish two basic definitions.

Tax evasion is the concealment of income, the falsification of records, or the failure to declare income that should be declared.

Tax avoidance is the lawful use of the rules, exemptions, timing, or legal structure of the tax system to one’s advantage.

The intent to avoid tax does not, in itself, turn legal behaviour into illegal behaviour. Intent alone is not a crime.

This is where the burden of proof matters.

In criminal law, where liberty is at stake, the burden of proof is extraordinarily high. Guilt must be established beyond a reasonable doubt, often requiring unanimous juries.

In contract law, on the other hand, any ambiguity is interpreted against the drafter of the contract.

But tax law is different. The state writes the law, enforces the law, and collects the money. Intuitively, this places tax law closer to criminal law than to contract law in terms of coercive power: you are compelled to surrender part of your income.

Yet in many jurisdictions, including the UK, the state has introduced General Anti‑Avoidance Rules (GAAR), designed to capture the “spirit” of the law rather than its text. This creates an inherent tension. The state writes the rules, enforces the rules, and benefits financially from the outcome, yet asks courts to reinterpret those same rules in its favour.

This asymmetry works only in one direction. The taxpayer never gets to revisit past decisions and reframe their tax planning if it later becomes clear that a different, fully legal option would have produced a lower tax burden.

Consider a simple example. Suppose that for every pound earned above £150,000 per year, the marginal tax rate is 90 per cent. One entirely rational response would be to stop producing additional income. This reduction in taxable activity is not evasion. The outcome of withheld production benefits no one.

Don’t laugh at the example. The famous Swedish children’s book author, Astrid Lindgren, once complained that she paid over 100 per cent tax on her royalties. The highest marginal tax rate in U.S. history was 94 per cent, and it applied during World War II, specifically from 1944 to 1945.

In 1974–1975, under the Labour government, the top marginal income tax rate in the UKreached 83 per cent. If you add the 15 per cent investment income surcharge, the marginal tax rate could reach 98 per cent.

Is choosing leisure over additional, highly taxed income a form of tax avoidance? For some taxpayers, the breaking point is not 90 per cent but 50 per cent. If they do not get to keep even half of what they earn, they lose interest in producing more.

Now consider someone who is exceptionally handy and takes time off work to improve their primary residence in a jurisdiction with a tax-free capital gains regime. Economic value is still being created, but income has effectively been converted into a tax-free gain. Is this “gaming the system,” or is it simply responding to the incentives the system deliberately provides?

Tax incentives and business behaviour

Tax authorities cannot tell you how to run your business. Their role is to tax the results of your business activities, not to speculate about what you should have done differently.

In some jurisdictions, privately held corporations may distribute lower-taxed dividends to owners based on payroll size. The more a business expands its operations and hires employees, the larger the pool of lower-tax dividends available to the owners. These incentives are explicitly designed to encourage employment. They work as intended but they also create a tax advantage for owners.

There is even a credible argument that corporations should not pay tax at all, but instead be treated like pension plans, with income taxed only in the hands of owners when it is distributed.

Imagine you have realised substantial capital gains during the year. In December, you discover that you also hold shares with unrealised losses. Is it unreasonable to realise those losses while they are available to offset the gains? Or would you consider that inappropriate planning?

Let’s take some examples across various jurisdictions, in which each country writes its own tax laws and sets its own rules. That fact matters.

For the first example, let’s consider a father living in the UK who started a company many years ago for £1. Today, it has a fair market value of £100 million. He learns that he has no more than six months to live. He has a daughter who lives in Sweden and will inherit the company. Under UK law, the father’s estate would be subject to UK inheritance tax on the £100 million value. Under Swedish law, the daughter would inherit the company along with her father’s original acquisition cost of £1. If she later sold the company for £100 million, she would owe Swedish capital gains tax on the full gain. Would it be inappropriate for the daughter to sever her tax ties with Sweden and move to the UK in order to avoid double taxation? In the UK, she would inherit the company at fair market value, and no further tax would be due upon sale.

For example two, let’s start with the fact that, in the UK, a primary residence can be sold without capital gains tax. Suppose, therefore, that you live in the UK and plan to move to Sweden. If you were to sell your residence before moving, the sale is tax-free, and you arrive in Sweden with cash that has already been taxed at zero rate. If, instead, you move to Sweden first and sell your former UK residence after becoming a Swedish tax resident, Sweden will tax the gain based on the difference between your original acquisition cost and the sale price. Would selling the residence before moving be inappropriate tax planning?

And for our final example, imagine you live in Sweden and have just come up with something so groundbreaking that your income for the next four years will be £20 million per year. More than half of this will disappear in taxes if you remain in Sweden. However, if you sever your ties with Sweden and move to the UK, you will be completely tax-free for the first four years of your residence there, as long as your income is generated outside the UK and even if you bring the income into your new home country for consumption and investment. Isn’t it, at the very least, a powerful incentive?

A steelman of the opposing view

Critics of expansive tax planning would argue that strict legality is not a sufficient standard for a fair tax system. They would contend that highly technical compliance can undermine the purpose of tax laws, erode public trust, and shift the burden onto those least able to bear it. From this perspective, GAAR provisions are not an arbitrary power grab but a necessary response to sophisticated planning that lawmakers cannot fully anticipate in advance. Without some ability to look beyond form to substance, the argument goes, the tax base becomes fragile, voluntary compliance weakens, and democratic consent to taxation is threatened, especially when the most resourceful taxpayers consistently achieve outcomes unavailable to ordinary earners.

Taken together, these examples show how ordinary, lawful decisions are routinely recast as suspect once tax enters the conversation. Many of the choices described here will feel familiar, because they arise from incentives deliberately written into the rules. The tension begins when legal certainty is displaced by moral judgement, and when behaviour that follows the law is treated as though it were a breach of it.

A tax system depends on clarity, predictability and equal application. Public debate may judge outcomes uneven, yet legislation remains the only instrument capable of defining what is permitted and what is not.

Harry Margulies is a journalist, author, commentator, and public intellectual whose work interrogates religion, politics, and morality with sharp wit and fearless clarity. A second-generation Holocaust survivor, he was born in Austria and spent time in an Austrian refugee camp before moving to Sweden. Educated by Orthodox rabbis throughout his childhood, he ultimately abandoned faith in his teens—a journey that has shaped his lifelong commitment to secularism, critical thinking, and freedom of expression. His latest book, Is God Real? Hell Knows, has been described by ABBA’s Björn Ulvaeus as “funny, sharp, and unafraid.”

READ MORE: ‘The limits of good intentions in public policy‘. Although public systems are often created with the best of intentions and rooted in compassion, they begin to struggle when those who design them fail to consider how real people respond to incentives, boundaries and opportunity. Drawing on examples from tax law, welfare, asylum policy and international governance, Harry Margulies argues that reluctance to confront predictable misuse early on leads to public distrust, political backlash and reforms far harsher than steady enforcement would ever have required.

Do you have news to share or expertise to contribute? The European welcomes insights from business leaders and sector specialists. Get in touch with our editorial team to find out more.

Main image: The Riksdag in Stockholm. Tax outcomes often depend less on morality than on the rules written by national legislatures (Pixabay)

RECENT ARTICLES

-

The era of easy markets is ending — here are the risks investors can no longer ignore

The era of easy markets is ending — here are the risks investors can no longer ignore -

Is testosterone the new performance hack for executives?

Is testosterone the new performance hack for executives? -

Can we regulate reality? AI, sovereignty and the battle over what counts as real

Can we regulate reality? AI, sovereignty and the battle over what counts as real -

NATO gears up for conflict as transatlantic strains grow

NATO gears up for conflict as transatlantic strains grow -

Facial recognition is leaving the US border — and we should be concerned

Facial recognition is leaving the US border — and we should be concerned -

Wheelchair design is stuck in the past — and disabled people are paying the price

Wheelchair design is stuck in the past — and disabled people are paying the price -

Why Europe still needs America

Why Europe still needs America -

Why Europe’s finance apps must start borrowing from each other’s playbooks

Why Europe’s finance apps must start borrowing from each other’s playbooks -

Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes

Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes -

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others -

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again -

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart?

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart? -

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing -

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage -

The limits of good intentions in public policy

The limits of good intentions in public policy -

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament?

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament? -

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth -

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours -

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality -

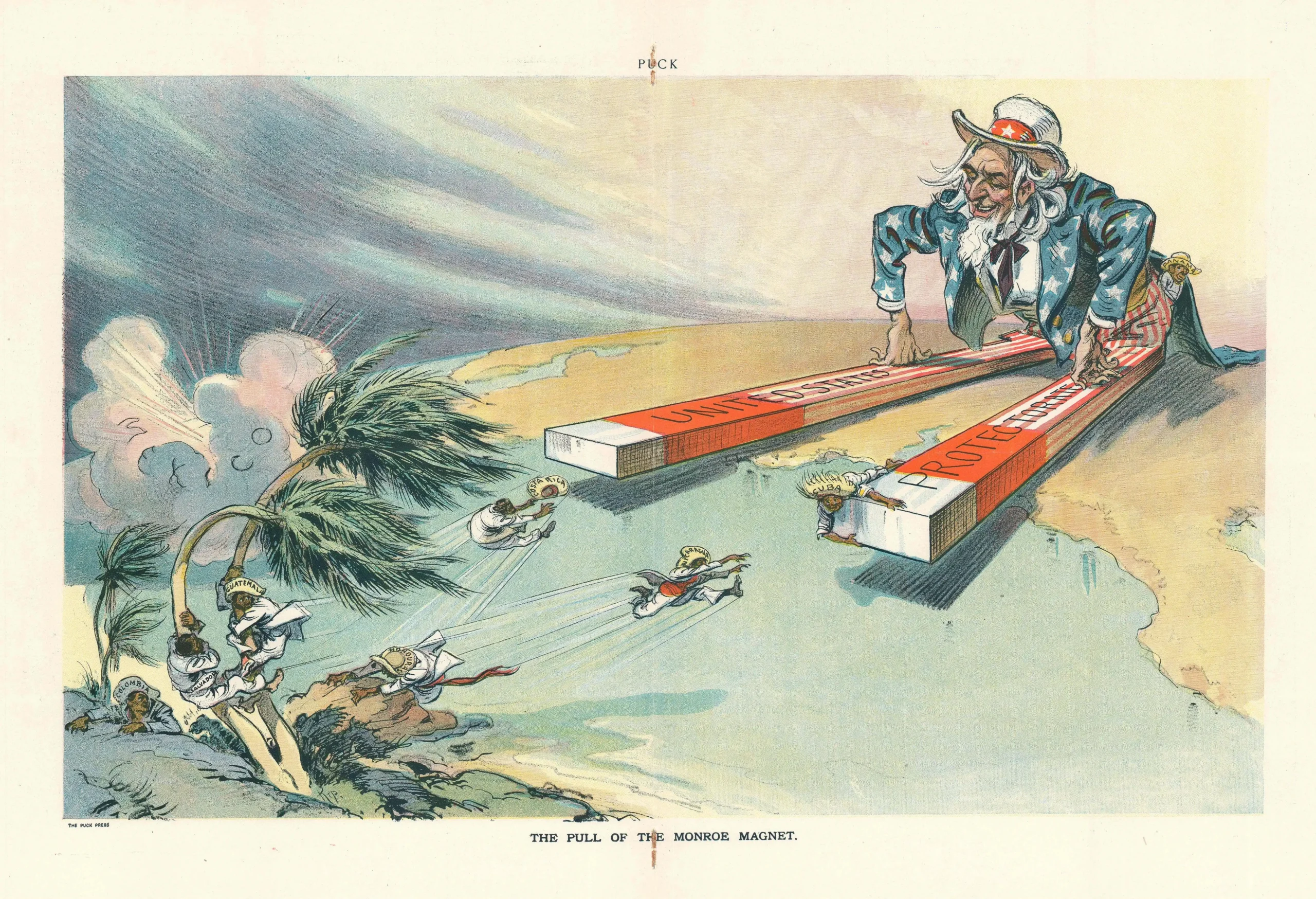

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now -

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day -

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy -

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it -

What if he falls?

What if he falls? -

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world