The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart?

Marco Previero

- Published

- Opinion & Analysis

Marco Previero, whose daughter survived cancer at seven, welcomes the Government’s 10-year plan and its overdue focus on children and young people. Writing from experience, he argues that its success will be measured by how well it supports not only diagnosis and cure, but the quality of life young survivors are able to lead afterwards

The new 10-year national cancer plan for England pledges to be a “break from the past” and puts the patients’ needs front and centre. It sets out an ambitious ‘moonshot’: that by 2035, three in four people diagnosed with cancer will be cancer-free or living well five years later. To reach that goal, it prioritises earlier diagnosis, innovation including AI, greater patient empowerment through the NHS App, and sustained investment in research.

Importantly, and for the first time, it identifies children and young people (CYP) as a separate category where improvement is necessary. It acknowledges that government policy had often focused insufficiently on outcomes for CYP, and on rare cancers. Writing from a place of personal gratitude, I note that Professor Darren Hargraves now co-chairs the re-established Children and Young People’s Cancer Task Force alongside Dame Caroline Dineage and Dr Sharna Shanmugavadivel. He was my daughter’s paediatric oncologist when she was undergoing brain cancer treatment at Great Ormond Street Hospital. Her life was saved under his careful guidance, and the centre of excellence in which he worked. My lived experience, and the lived experience of many children and parents before and after us, matters and underscores why this particular chapter of the plan must be put into action with real commitment.

The translation from promise to result will, as always, be the hardest part, but we should welcome this plan, and the intentions behind it. Much in it looks right, if somewhat flooded with targets. It could have been written by engineers. For example, diagnostic capacity will be significantly expanded, with 9.5 million additional tests each year by 2029. This will be supported by digital pathology and automation aimed at achieving a 10-day histopathology turnaround in 98% of cases by the same date. When my daughter was diagnosed in 2013, a clinician was manually counting cells and matching patterns of cancerous growth on a petri dish.

Early diagnosis is a central priority, with national lung cancer screening in place by 2030, enhanced bowel screening, and cervical self-sampling scaled by 2029. All of this will be visible to patients through a redesigned NHS App, intended to serve as a dashboard for cancer prevention with direct access to tests and self-referral.

The plan also reflects a welcome shift in emphasis towards life after treatment, which is especially important for certain cancers and particularly for paediatric brain tumours, where as many as 80 per cent of children are now cured yet live with lifelong disabilities.

Much of this is long overdue: standard psychological assessments from diagnosis through follow-up, and a named neurorehabilitation keyworker from the outset for every young person with a CNS tumour (central nervous system, most often brain cancer).

In some areas, such as rehabilitation and psychological care, especially for CYP, the plan probably does not go far enough. A greater emphasis on translating some of these principles into enforceable access standards could have been included, such as psychological assessment within two weeks of diagnosis, ongoing support within four weeks post treatment neurorehabilitation plan within a fortnight of a CNS diagnosis, measured support through transitions to adult services. We lived this last transition poorly, despite its critical nature. Without binding standards, this “below par” transition of care will continue to adversely affect the lives of young adults moving away from paediatric centres of excellence such as Great Ormond Street Hospital.

It was disappointing, given the difficulties my daughter faced, that the plan does not fully treat education and employment or vocational outcomes as core health measures. A meaningful scorecard would track what matters most to young lives: school attendance and attainment, cognitive recovery, fatigue management, mental health, and fertility support. These are the essentials of a life worth living, and this support should be guaranteed rather than left to chance.

Finally, the plan turns to AI, widely regarded as central to the future of healthcare, even if for many its meaning still feels abstract beyond novelty uses and optimistic commentary, and frames it in practical terms as a tool to release time to care across the cancer workforce. It does so pragmatically: image reading, radiotherapy planning, exploiting ‘circulating tumour DNA’ (using clues from tumour DNA in the blood to speed up treatment), and operational AI to speed up clinical pathways. This focus on AI for diagnostic and treatment efficiency has not been matched with the same innovative vision for ‘life after treatment”. For survivors, the tech ambition seems to wane just when consistent, long-term care is needed most. These gaps exist, inevitably, because these are areas that are hard to measure.

All in all, the plan aims to build strong foundations in early diagnosis, diagnostic productivity, research acceleration, patient empowerment, and a serious focus on inequity of care (some postcodes fare better than others). For children and young people, the future looks a little brighter, and is stewarded by professionals who understand the stakes, like Professor Darren Hargreaves. Families like mine have experienced first-hand what excellence looks like under pressure, in particular during the acute treatment phase.

Now comes the hard part: ensuring this project does not follow the path of HS2, becoming a high-profile promise that stalls, overruns, and fails to deliver in time for those it is meant to serve. For the plan to be credible right from the get-go, it needs to be delivered at pace, in every region, backed by investment, workforce, data transparency, and expansion of AI into rehabilitation and long-term support. If it does that, and I hope it does, it will help every person diagnosed with cancer, every child and every young adult, live fully, during treatment and long after it ends.

Marco Previero is a health-innovation commentator and patient advocate specialising in survivorship, rehabilitation and user-centred models of care. His perspective is informed by twelve years navigating paediatric oncology as the father of a childhood brain cancer survivor, with experience spanning acute treatment, long-term follow-up across multi-disciplinary specialism (specialist rehabilitation, neurocognitive support, endocrinology, and psychosocial services, education support), and the systems that shape recovery. A former founding Trustee of SUCCESS Life After Cure Ltd and a named contributor to a 2025 North Thames Paediatric Cancer Network and Great Ormond Street Hospital study, he writes for The European on patient experience, survivorship, health innovation and the future of care pathways.

READ MORE: ‘European Commission issues new cancer prevention guidance as EU records 2.7m cases in a year‘. Updated European Code Against Cancer published on World Cancer Day as Brussels marks five years of its Beating Cancer Plan and warns that many cases remain preventable.

Do you have news to share or expertise to contribute? The European welcomes insights from business leaders and sector specialists. Get in touch with our editorial team to find out more.

Main image: CDC/Pexels

RECENT ARTICLES

-

Europe cannot call itself ‘equal’ while disabled citizens are still fighting for access

Europe cannot call itself ‘equal’ while disabled citizens are still fighting for access -

Is Europe regulating the future or forgetting to build it? The hidden flaw in digital sovereignty

Is Europe regulating the future or forgetting to build it? The hidden flaw in digital sovereignty -

The era of easy markets is ending — here are the risks investors can no longer ignore

The era of easy markets is ending — here are the risks investors can no longer ignore -

Is testosterone the new performance hack for executives?

Is testosterone the new performance hack for executives? -

Can we regulate reality? AI, sovereignty and the battle over what counts as real

Can we regulate reality? AI, sovereignty and the battle over what counts as real -

NATO gears up for conflict as transatlantic strains grow

NATO gears up for conflict as transatlantic strains grow -

Facial recognition is leaving the US border — and we should be concerned

Facial recognition is leaving the US border — and we should be concerned -

Wheelchair design is stuck in the past — and disabled people are paying the price

Wheelchair design is stuck in the past — and disabled people are paying the price -

Why Europe still needs America

Why Europe still needs America -

Why Europe’s finance apps must start borrowing from each other’s playbooks

Why Europe’s finance apps must start borrowing from each other’s playbooks -

Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes

Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes -

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others -

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again -

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart?

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart? -

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing -

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage -

The limits of good intentions in public policy

The limits of good intentions in public policy -

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament?

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament? -

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth -

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours -

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality -

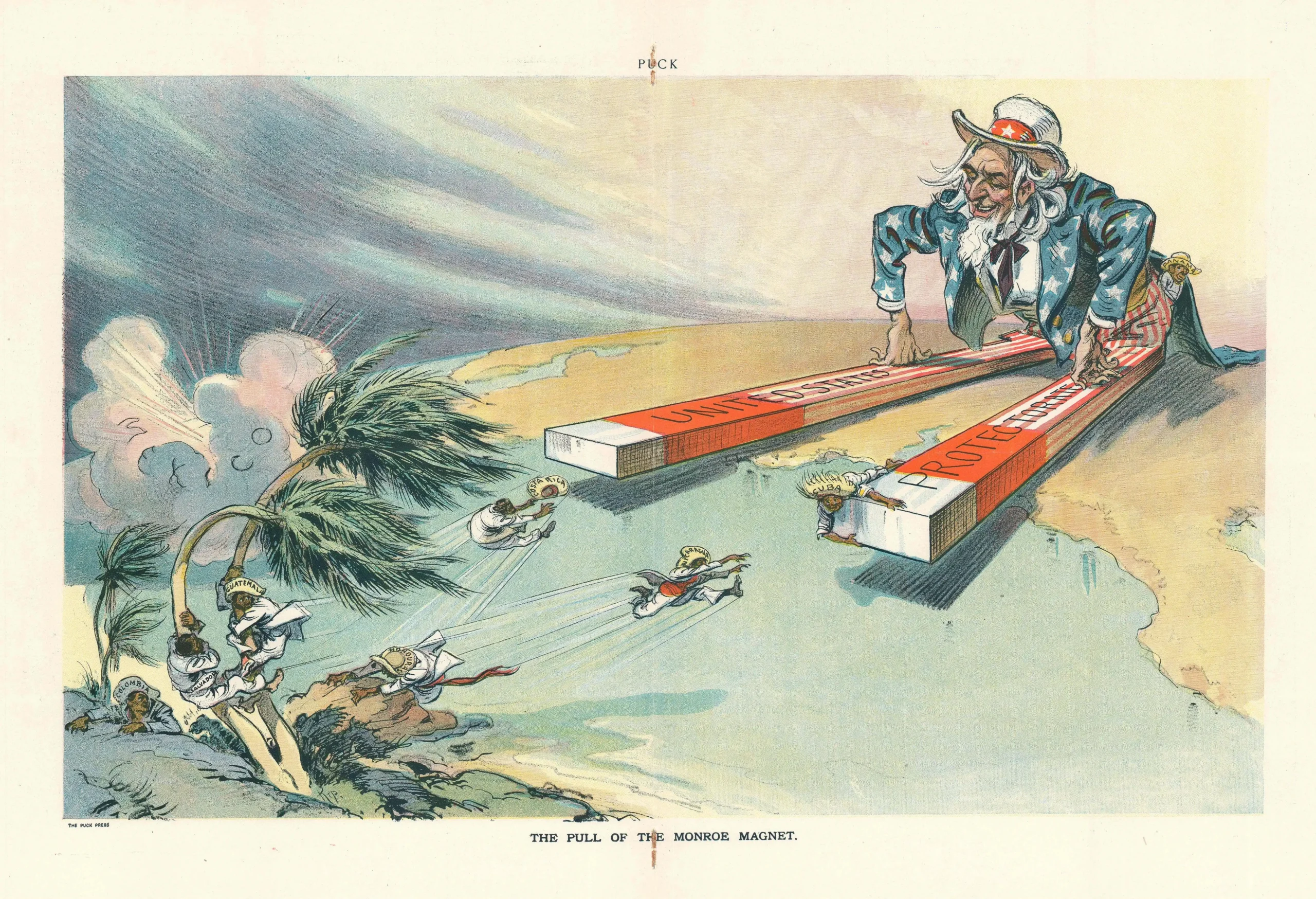

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now -

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day -

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy -

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it