Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours

Marco Previero

- Published

- Opinion & Analysis

While medical advances now allow most children with brain tumours to live for decades after diagnosis, the system still fails to measure, model, and properly fund the long-term rehabilitation that determines how well they live those years. Marco Previero, our Health Innovation Correspondent, draws on his daughter’s recovery to show why rehabilitation deserves the same rigour, funding, and policy attention as treatment

Twelve years after my daughter’s brain tumour was declared ‘cured’, we still organise our daily lives around its consequences.

Fatigue from synthetic hormones shapes her days, speech and language difficulties affect how she communicates, and learning and behavioural challenges followed her into school, friendships, and independence. These are described in clinical notes as “side-effects”. I prefer to call them what they are: hidden disabilities that arrived with the treatment that saved her life.

My daughter is one of a generation of children who now survive brain cancer in numbers that would have been unimaginable a few decades ago, with around eighty per cent of children diagnosed today expected to live for an average of sixty-eight years after diagnosis. Survival has improved dramatically.

What happens after survival, however, has never been approached with the same commitment.

An estimated 12,700 people will be diagnosed with a brain tumour this year, and The Brain Tumour Charity calculates that those cases alone carry a lifetime economic impact of £18.7 billion across the UK, a figure that equates to the annual salaries of roughly 350,000 nurses, around 1.9 million child-years of comprehensive neurorehabilitation, or close to a month of NHS England’s total running costs.

Those numbers matter because they are large. They also matter because they reveal where the system attributes value to the analysis, and where it places its bets.

The report’s modelling and recommendations lean toward faster diagnosis and cure, while children’s rehabilitation – the support that determines who returns, and how quickly, to learning, friendships, communication, and independence – remains vague and poorly measured. We need a shift in the way we think about innovation in this area, from cure alone to better quality of survival, with rehabilitation given the same rigour, funding, resourcing, and accountability as treatment research.

While the report’s findings are valuable, they highlight a systematic and persistent imbalance in modern brain cancer research. The framing, methodology, and scenarios presented, focus predominantly on an ability to diagnose and understand the biological pathways of the disease in order to cure it, an approach that is understandable yet often comes at the expense of a more holistic view, particularly when it comes to recovery and rehabilitation.

Brain cancer is a special kind of cancer because of where it grows: the brain, which holds within its folds our childhoods, the memory of our first heartbreak, how we love, who we love, what makes us happy, what makes us sad, what type of latte we like, our habits, our grief, and where we last saw our car keys. Any cure needs to strike a delicate balance between eradicating the disease and preserving as much of that “us” as possible. This is not true of any other cancer.

Around two-thirds of childhood brain cancer survivors experience more than one significant, long-term, sensory, neurological, and life-threatening disability, with many living with five or six.

Support and access to essential rehabilitative services across those decades remains uneven. When services arrive early and consistently, or when parents have independent means to support them, children move forward. When they do not, children stall and fall behind.

The Brain Tumour Charity report captures the economics of that reality. The recommendations for policy response still lean toward cure and detection rather than long-term, sustained rehabilitation. Rehabilitation is mentioned as one of six recommendations in the conclusion, and it does not go far enough.

Part of the challenge is that we have more data about diagnosis and cure than we have about longer-term measures of quality of life, and what gets counted drives decisions.

The York Health Economics Consortium model commissioned by the charity focuses on survival and macro-productivity. Rehabilitation sits inside a small “care” category valued at £78 million and is described as under-estimated for parts of the pathway, especially for non-malignant tumours, due to limited data.

I took part in a recent evaluation by the North Thames Paediatric Cancer Network in collaboration with Great Ormond Street Hospital. We found that, while NHS recommendations recognise the importance of rehabilitation in improving long-term quality of life, they do not set out how services should be structured or what children should receive in terms of frequency, duration, and timeframe.

Quantifying only what can easily be measured creates bias by building cases for interventions that fit narrow accounting.

The report includes one quantified improvement scenario in which diagnosing two weeks earlier reduces lifetime costs by around £800 million. There is no equivalent scenario modelling the impact of expanded paediatric neurorehabilitation assessment or integrated school support, even though these shape children’s lives as adults.

Recommendations mirror the structure of the modelling. The report calls for faster diagnostic pathways and sustained research funding, while also calling for guaranteed rehabilitation and specialist education support without national costing, workforce targets, minimum service standards, or defined intensity and timing across a survivor’s lifetime.

Families, including mine, live the gap between survival and recovery for an average of sixty-eight years after diagnosis – a lifetime.

The report makes a strong economic case for urgent action. This is commendable. The next step is to give rehabilitation the same modelling depth, costing, and delivery framework that diagnosis and treatment research already receive. Families like mine see the difference when rehabilitation works. Policy can measure it, fund it, and deliver it at scale.

The lives of 12,700 adults and children each year depend on that.

Marco Previero is a health-innovation commentator and patient advocate specialising in survivorship, rehabilitation and user-centred models of care. His perspective is informed by twelve years navigating paediatric oncology as the father of a childhood brain cancer survivor, with experience spanning acute treatment, long-term follow-up across multi-disciplinary specialism (specialist rehabilitation, neurocognitive support, endocrinology, and psychosocial services, education support), and the systems that shape recovery. A former founding Trustee of SUCCESS Life After Cure Ltd and a named contributor to a 2025 North Thames Paediatric Cancer Network and Great Ormond Street Hospital study, he writes for The European on patient experience, survivorship, health innovation and the future of care pathways.

READ MORE: ‘Curium’s expansion into transformative therapy offers fresh hope against cancer‘. Increased radioligand therapy options could transform cancer treatment by targeting tumours while reducing exposure to surrounding healthy tissue. Curium, a global leader in nuclear medicine, is moving to roll it out worldwide.

Do you have news to share or expertise to contribute? The European welcomes insights from business leaders and sector specialists. Get in touch with our editorial team to find out more.

Main image: Pavel Danilyuk/Pexels

RECENT ARTICLES

-

Facial recognition is leaving the US border — and we should be concerned

Facial recognition is leaving the US border — and we should be concerned -

Wheelchair design is stuck in the past — and disabled people are paying the price

Wheelchair design is stuck in the past — and disabled people are paying the price -

Why Europe still needs America

Why Europe still needs America -

Why Europe’s finance apps must start borrowing from each other’s playbooks

Why Europe’s finance apps must start borrowing from each other’s playbooks -

Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes

Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes -

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others -

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again -

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart?

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart? -

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing -

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage -

The limits of good intentions in public policy

The limits of good intentions in public policy -

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament?

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament? -

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth -

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours -

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality -

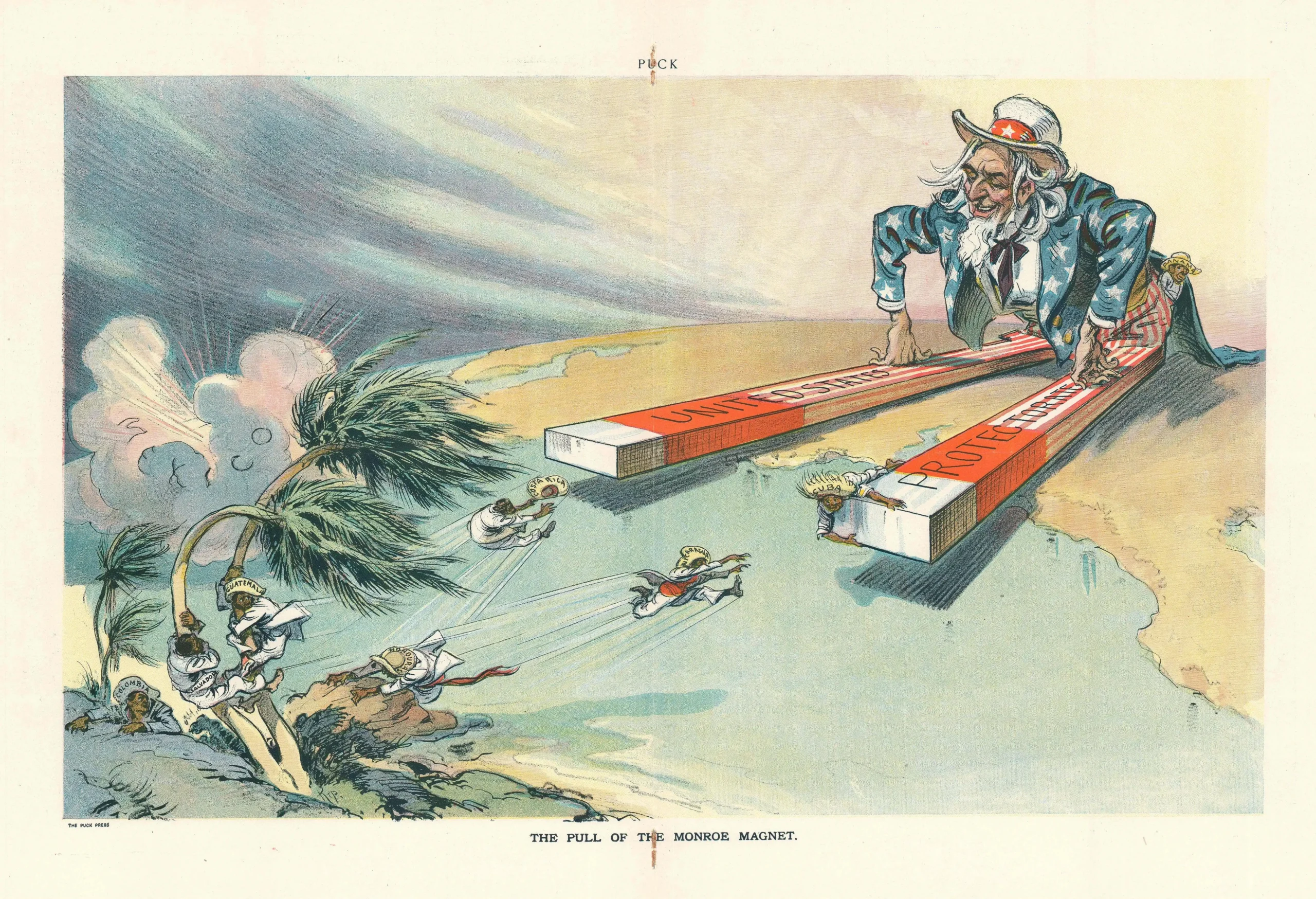

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now -

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day -

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy -

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it -

What if he falls?

What if he falls? -

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world -

Will Trump’s Davos speech still destroy NATO?

Will Trump’s Davos speech still destroy NATO? -

Philosophers cautioned against formalising human intuition. AI is trying to do exactly that

Philosophers cautioned against formalising human intuition. AI is trying to do exactly that -

Life’s lottery and the economics of poverty

Life’s lottery and the economics of poverty -

On a wing and a prayer: the reality of medical repatriation

On a wing and a prayer: the reality of medical repatriation