Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again

Dr Stephen Whitehead

- Published

- Opinion & Analysis

When sociologist Dr Stephen Whitehead found himself almost persuaded by a paragraph produced in seconds by artificial intelligence, it triggered an uncomfortable realisation about how easily polished words can pass for finished thought — and what that means for the way we now use our own minds

I have spent more than three decades studying how people think, justify themselves, and make sense of the world. I’ve interviewed thousands of people in that time, filled shelves with books and journals on the subject, written many of them myself, and spent long periods in libraries and lecture halls trying to understand how ideas take shape.

I thought I understood that process well.

And then, in a matter of seconds, artificial intelligence exposed something I had missed. I had asked it to reframe a point I was struggling to express and it returned a paragraph that did so almost immediately. Its suggestion was so persuasive that I almost accepted it without question.

My own reaction caught my attention. I have often heard people say a belief or decision “felt right” for no other reason than the explanation they were given for it was coherent and eloquently put. I recognised the same response in myself when reading text produced by a system designed to generate coherency and eloquence on demand.

The speed with which AI reorganised my material wrong-footed me in that it created the sense that the intellectual work had already taken place. I saw how easily the human mind can treat a tidy explanation as evidence of finished thinking.

When well-argued and articulate words arrive on our screens in this way, it is very easy to feel as though the thinking behind them has already been completed and that we are no longer needed.

To be clear, I do not ask AI to write my work for me. I do use it, however, to help me notice what might be missing and to test how well my ideas are put together. The replies it gives are usually helpful and for the most part reduce the stress of finding the right words to convey what I’m trying to say.

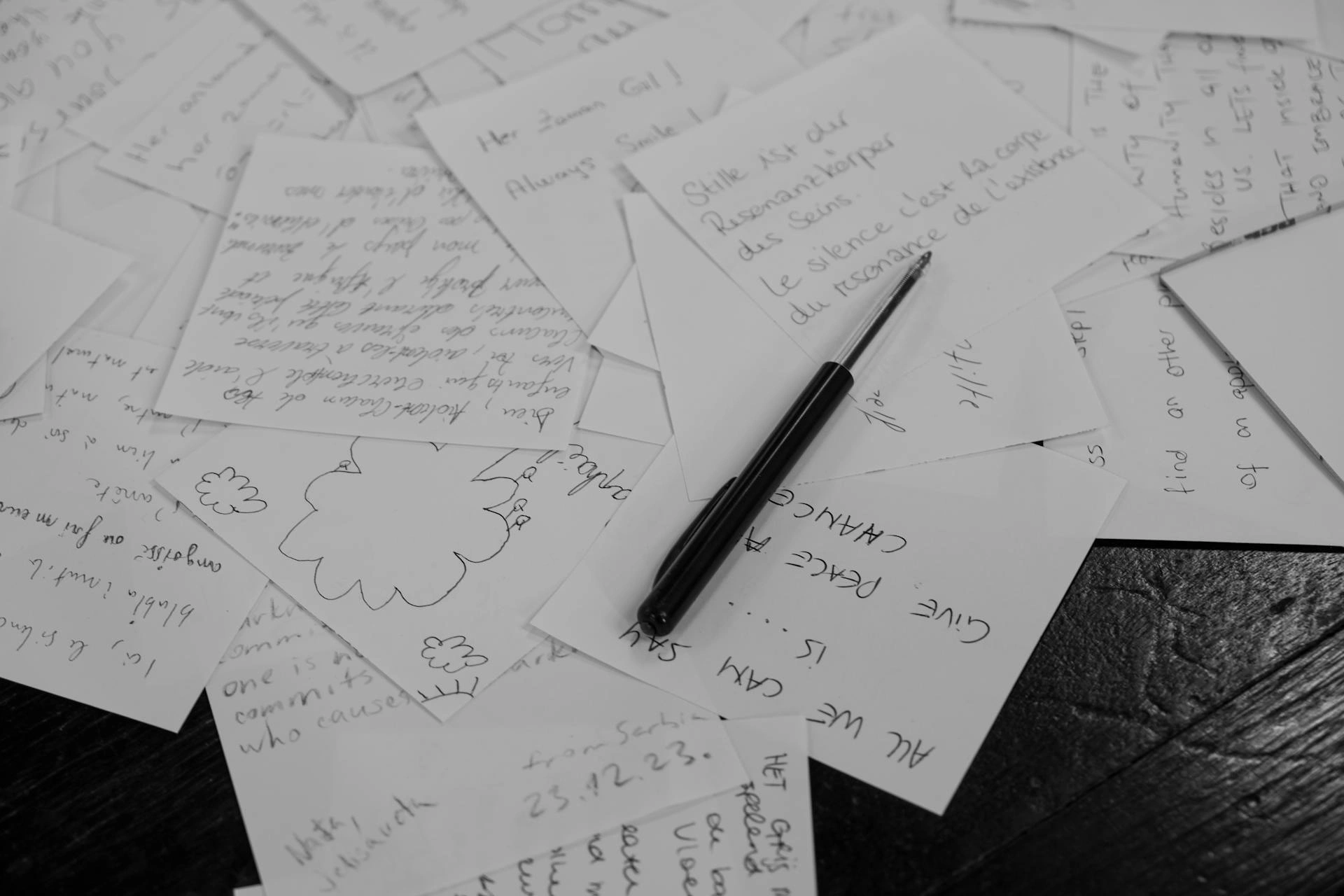

And yet it is precisely this stress – the inner-wrestling with how to best convey a point – that plays an important role in real thought. Much of the work of human understanding happens while we attempt to explain something properly. This, in turn, gives us the opportunity to change our mind, to cross things out, and to return later with a clearer view. AI moves past that analysis stage by offering a version that looks finished before we have fully worked it through for ourselves.

For most of my life, my own thinking developed through notebooks filled with scribbles, books marked in pencil, and long walks where ideas gradually settled into shape. The advent of AI has shaken that up for me and, I would think, for billions of others worldwide. It is remarkably good at remembering earlier points, organising untidy material, and arranging ideas into a clear structure. At times, I freely admit this can be a relief. But at the same time, it can begin to carry out some of the joining-up that normally happens through doubt, revision and explanation. It presents our unfinished thoughts – those that would normally take a long walk, conversations, or a bottle of wine to ferment – as complete thanks to eloquent language and coherency.

As AI becomes part of everyday life, an important question is how to use it without handing over our responsibility for thinking.

In my case, I treat what AI produces as a helpful draft that still needs my attention. I see it as a slightly clearer version of the scribbled notes I used to make in notebooks, much like a personal assistant transcribes an audio note into something legible. I do not, however, rely on it unless I can restate the same idea in my own words without borrowing its eloquent phrasing.

The ideas I use in my own work developed over many years and remain imperfect in ways I can describe plainly to anyone who asks. This provides a useful guide, since any idea that cannot be explained in simple language to a curious friend probably needs more thought.

Ideas become stronger when other people question them, misunderstand them, and push back against them. Those moments of friction reveal what is unclear and what needs further work.

I bring my ideas to AI and ask it to test their structure, but I also take them to other people who challenge them in different ways. Thinking benefits from the effort of explanation, the patience required to listen, and the presence of disagreement.

AI can help make ideas clearer, certainly. But other people help show whether those ideas genuinely make sense.

Our brains are eclectic, imperfect and often unable to say exactly what we mean, and it is precisely that messy, searching quality that makes human thinking far richer than anything AI can produce.

Dr Stephen Whitehead is a sociologist, author and consultant internationally recognised for his work on gender, leadership and organisational culture. This article draws on a chapter from Design Your Self: 21 Life Lessons (Vanguard Press, 2025). His most recent book is The End of Sex: The Gender Revolution and Its Consequences (Acorn, 2025).

READ MORE: ‘Philosophers cautioned against formalising human intuition. AI is trying to do exactly that‘. The daily use of AI in research and writing is creating a new cognitive environment in which human judgment operates in tandem with computational systems. This development carries educational, philosophical and democratic implications that demand scrutiny, argues sociologist Dr Stephen Whitehead.

Do you have news to share or expertise to contribute? The European welcomes insights from business leaders and sector specialists. Get in touch with our editorial team to find out more.

Main image: Scattered notes and half-formed thoughts on paper capture the messy, searching process of human thinking before ideas settle into clarity. (Kağan Karatay/Pexels)

RECENT ARTICLES

-

The era of easy markets is ending — here are the risks investors can no longer ignore

The era of easy markets is ending — here are the risks investors can no longer ignore -

Is testosterone the new performance hack for executives?

Is testosterone the new performance hack for executives? -

Can we regulate reality? AI, sovereignty and the battle over what counts as real

Can we regulate reality? AI, sovereignty and the battle over what counts as real -

NATO gears up for conflict as transatlantic strains grow

NATO gears up for conflict as transatlantic strains grow -

Facial recognition is leaving the US border — and we should be concerned

Facial recognition is leaving the US border — and we should be concerned -

Wheelchair design is stuck in the past — and disabled people are paying the price

Wheelchair design is stuck in the past — and disabled people are paying the price -

Why Europe still needs America

Why Europe still needs America -

Why Europe’s finance apps must start borrowing from each other’s playbooks

Why Europe’s finance apps must start borrowing from each other’s playbooks -

Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes

Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes -

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others -

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again -

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart?

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart? -

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing -

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage -

The limits of good intentions in public policy

The limits of good intentions in public policy -

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament?

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament? -

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth -

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours -

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality -

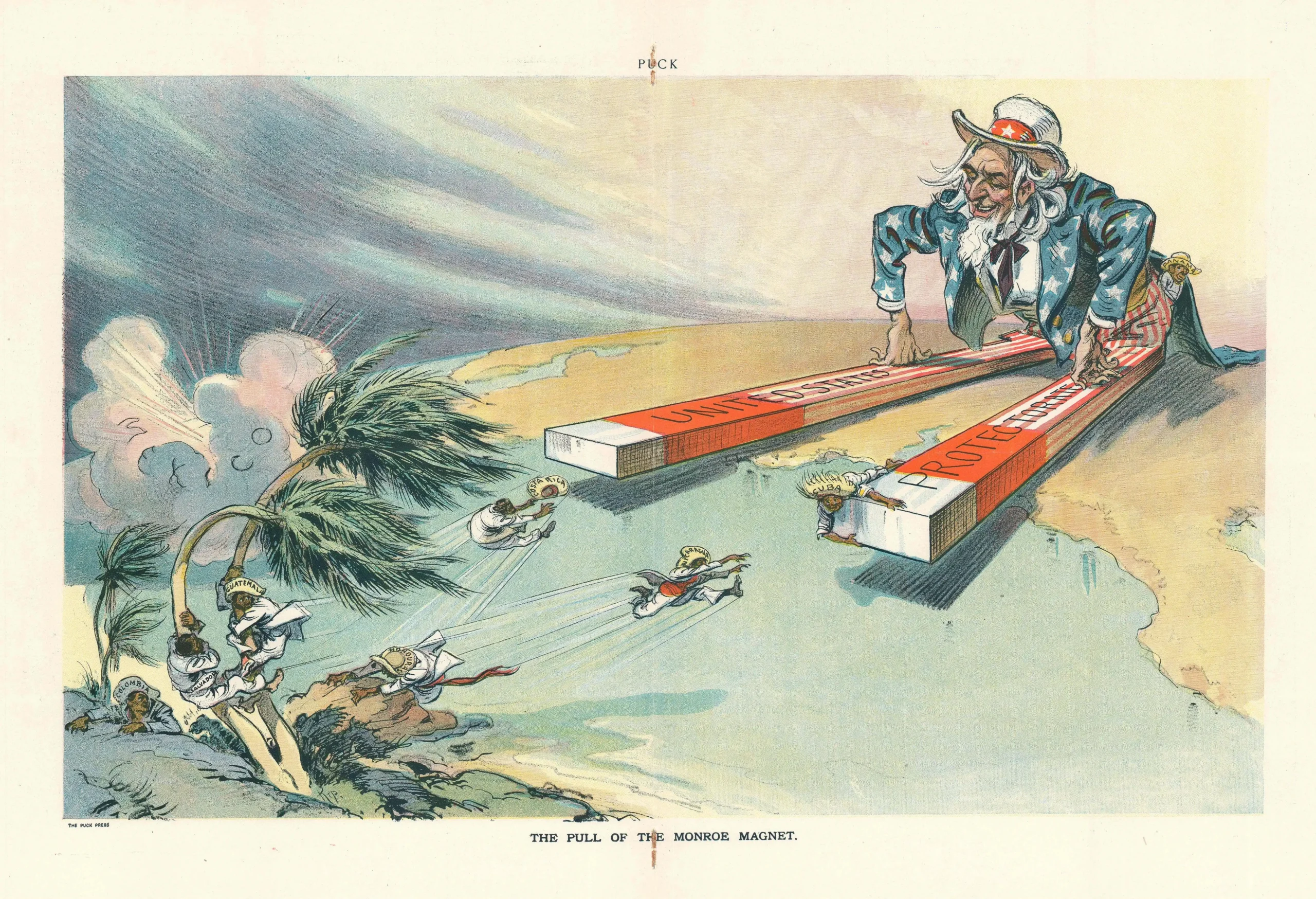

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now -

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day -

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy -

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it -

What if he falls?

What if he falls? -

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world