The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others

Dr Stephen Whitehead

- Published

- Opinion & Analysis

Why do some leaders seem to defy the odds while others unravel despite every conceivable advantage? Examining the cases of prominent historical figures such as Napoleon and Eisenhower, sociologist Dr Stephen Whitehead explores why luck, timing and self-belief matter just as much as talent—and sets out six lessons for anyone who wants fortune on their side

LISTEN: Dr Stephen Whitehead argues that what looks like leadership genius in figures from Napoleon to Eisenhower often rests on luck shaped by timing, humility, earned confidence, moral conduct and the wisdom to recognise when fortune is turning.

I am fascinated by famous dead men. From Napoleon Bonaparte to Genghis Khan, Julius Caesar to Winston Churchill, George Washington to Alexander the Great, I cannot get enough of them. It is not just their lives and adventures but also their grim determination to succeed in the face of ridiculous odds.

As a gender sociologist, their biographies help me understand the type of man who can build, and destroy, countries, cultures and even humanity itself. Whatever your view of their morality, ethics or integrity, they were unquestionably exceptional figures.

They were also lucky.

During his relatively short but momentous life, Napoleon Bonaparte left his mark not only on the battlefield but in his speeches, writings and conversation. One of his most famous remarks has stayed with me for years: “I’d rather have a general who was lucky than one who was good.”

Read his biography and you cannot miss how often he was extraordinarily fortunate. He repeatedly defied disaster, death and injury. While many around him were killed during his campaigns—through both victory and defeat—he remained standing. Until, that is, the day his luck finally ran out at the Battle of Waterloo. Even then, he did not die. He was exiled to St Helena, where he passed away almost six years later at the age of 51.

For most people, luck (or the lack of it) feels largely decided at birth: when, where and to whom you are born. It does not take a genius to recognise that being born into a prosperous family in a wealthy industrialised country is likely to make life easier than being born into poverty in the Horn of Africa.

But set aside place of birth for a moment. What makes some people lucky and others not? Why do some seem to float over life’s vicissitudes while others have suffering piled upon them, seemingly unfairly?

I believe I came closer to an answer after becoming a Buddhist more than twenty years ago. I began to understand the concept of karma: that actions today bring consequences tomorrow. Good actions are more likely to lead to good outcomes, and vice versa. How realistic is it to behave badly towards others and expect a life full of joy and good fortune? Some people appear to get away with it, but in my experience, no one does in the end. Eventually, luck runs out.

Apparently, Napoleon went into his final battle fearing just that—that his luck had deserted him. He sensed it, and he was right. Everything went badly on that Sunday in June 1815. His own karma finally caught up with him. He could have remained in relatively comfortable exile on Elba and lived into old age. Instead, he pushed his luck. It was a fatal decision.

Lucky Leader Lesson Number 1

Don’t push your luck. It will eventually turn on you. Always expect the unexpected, and never assume fortune will protect you indefinitely.

Lucky Leader Lesson Number 2

Good karma has to be earned and respected. What goes around comes around. Take it for granted, indulge in hubris or start behaving badly, and the wheels will come off.

Another famous believer in the idea of the ‘lucky leader’ was Dwight D. Eisenhower. One of the most successful Allied generals of the Second World War, Eisenhower later became the 34th President of the United States in 1953. He is often quoted as saying: “I would rather have a lucky general than a smart general. They win battles and make me lucky.”

Whether Eisenhower was religious is unclear, but he was certainly superstitious. He famously carried seven old coins in his pocket, including a gold five-guinea piece. A formidable military leader, yet still willing to believe in something far less rational than tanks or troop numbers.

He had something in common with one of England’s greatest football managers, Brian Clough. Clough was a legendary leader of trophy-winning teams in the 1970s and 1980s and a master of man-management. Yet he insisted on wearing his ‘lucky blue suit’ on matchdays.

Lucky Leader Lesson Number 3

It costs nothing to hedge your bets against misfortune. Even the best and brightest can be superstitious. Just don’t rely on it.

Over the years I have met leaders from all walks of life, including those seemingly born with a silver spoon of luck who still manage to be dogged by misfortune.

One example springs to mind. Born into a wealthy family, educated at all the right schools and universities, this person walked straight into the family business after graduating. A dream start. All they had to do was follow the well-trodden path laid out before them.

Instead, things unravelled. First, a bad marriage ended in divorce, with two children caught in the middle. Then came a complete family fallout that never healed. Most damaging of all, this person believed they were a far better leader than they actually were. They failed to recognise how much luck had carried them so far. Advice was ignored. Professional standards slipped. Poor decisions piled up. Eventually, the business collapsed.

I feel sympathy for such unlucky leaders. To some degree, destiny put them in that position. They became leaders through circumstance rather than merit. But the cause of failure is usually clear: an inflated, unjustified ego combined with a powerful sense of entitlement. Napoleon had an enormous ego—but he also had the achievements to match it. The leader with a big ego and no track record is courting disaster.

Lucky Leader Lesson Number 4

Every leader needs an ego. Make sure it is earned through effort and success, not inflated by entitlement or the belief that luck is owed to you.

From Queen Elizabeth I to Catherine the Great, Henry Ford to Elon Musk, one theme consistently emerges: timing.

Read any biography of a great leader and the idea of destiny appears again and again. The lucky leader believes, often fiercely, in their ‘moment’. They arrive on the stage of history at the right time, when doors are not necessarily open but can be forced. And so they push.

You do not have to be a global historical figure to recognise this feeling. Ordinary lives have their moments too. Timing matters. Even the right decision, taken at the wrong time, can end in failure.

Lucky Leader Lesson Number 5

Real luck lies in timing. You cannot measure it with clocks. Instead, you sense it. The lucky leader knows when to act decisively and when to hold back—and does not rely on others to tell them when that moment has arrived.

Finally, studying famous leaders reveals how confidence, determination and self-belief merge into something deeper: self-love. Napoleon certainly loved himself—and so did many other successful, egotistical leaders. They believed themselves worthy of success.

Perhaps this belief is the real source of luck: the conviction that one’s life has meaning and potential, and that something important must be achieved.

Which brings us to the final lesson.

Lucky Leader Lesson Number 6

Self-love must sit at the core of leadership—but tempered by realism and practical skill. Without self-belief, you will not reach the top. To lead others, you must first believe in your own value.

Luck runs out. Circumstances change. Do not be reckless, greedy or entitled. Do good rather than bad. Do not rely on superstition alone. Believe in yourself—and know when it is finally time to stop.

Yes, these are clichés. But few would deny their truth.

If you want to be a lucky leader, start by believing that you are one. Use all your intelligence at the right moment—and, just in case, keep your fingers crossed.

Dr Stephen Whitehead is a gender sociologist and author recognised for his work on gender, leadership and organisational culture. Formerly at Keele University, he has lived in Asia since 2009 and has written 20 books translated into 17 languages. He is based in Thailand and is co-founder of Cerafyna Technologies.

READ MORE: ‘Failure is how serious careers in 2026 will be shaped‘. Modern professional life frames failure as a negative outcome to be avoided. Dr Stephen Whitehead argues that it performs a practical function: testing judgement, correcting direction, and shaping how individuals make decisions about work, ambition and identity over time.

Do you have news to share or expertise to contribute? The European welcomes insights from business leaders and sector specialists. Get in touch with our editorial team to find out more.

Main image: Pixabay

RECENT ARTICLES

-

Europe cannot call itself ‘equal’ while disabled citizens are still fighting for access

Europe cannot call itself ‘equal’ while disabled citizens are still fighting for access -

Is Europe regulating the future or forgetting to build it? The hidden flaw in digital sovereignty

Is Europe regulating the future or forgetting to build it? The hidden flaw in digital sovereignty -

The era of easy markets is ending — here are the risks investors can no longer ignore

The era of easy markets is ending — here are the risks investors can no longer ignore -

Is testosterone the new performance hack for executives?

Is testosterone the new performance hack for executives? -

Can we regulate reality? AI, sovereignty and the battle over what counts as real

Can we regulate reality? AI, sovereignty and the battle over what counts as real -

NATO gears up for conflict as transatlantic strains grow

NATO gears up for conflict as transatlantic strains grow -

Facial recognition is leaving the US border — and we should be concerned

Facial recognition is leaving the US border — and we should be concerned -

Wheelchair design is stuck in the past — and disabled people are paying the price

Wheelchair design is stuck in the past — and disabled people are paying the price -

Why Europe still needs America

Why Europe still needs America -

Why Europe’s finance apps must start borrowing from each other’s playbooks

Why Europe’s finance apps must start borrowing from each other’s playbooks -

Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes

Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes -

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others -

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again -

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart?

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart? -

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing -

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage -

The limits of good intentions in public policy

The limits of good intentions in public policy -

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament?

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament? -

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth -

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours -

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality -

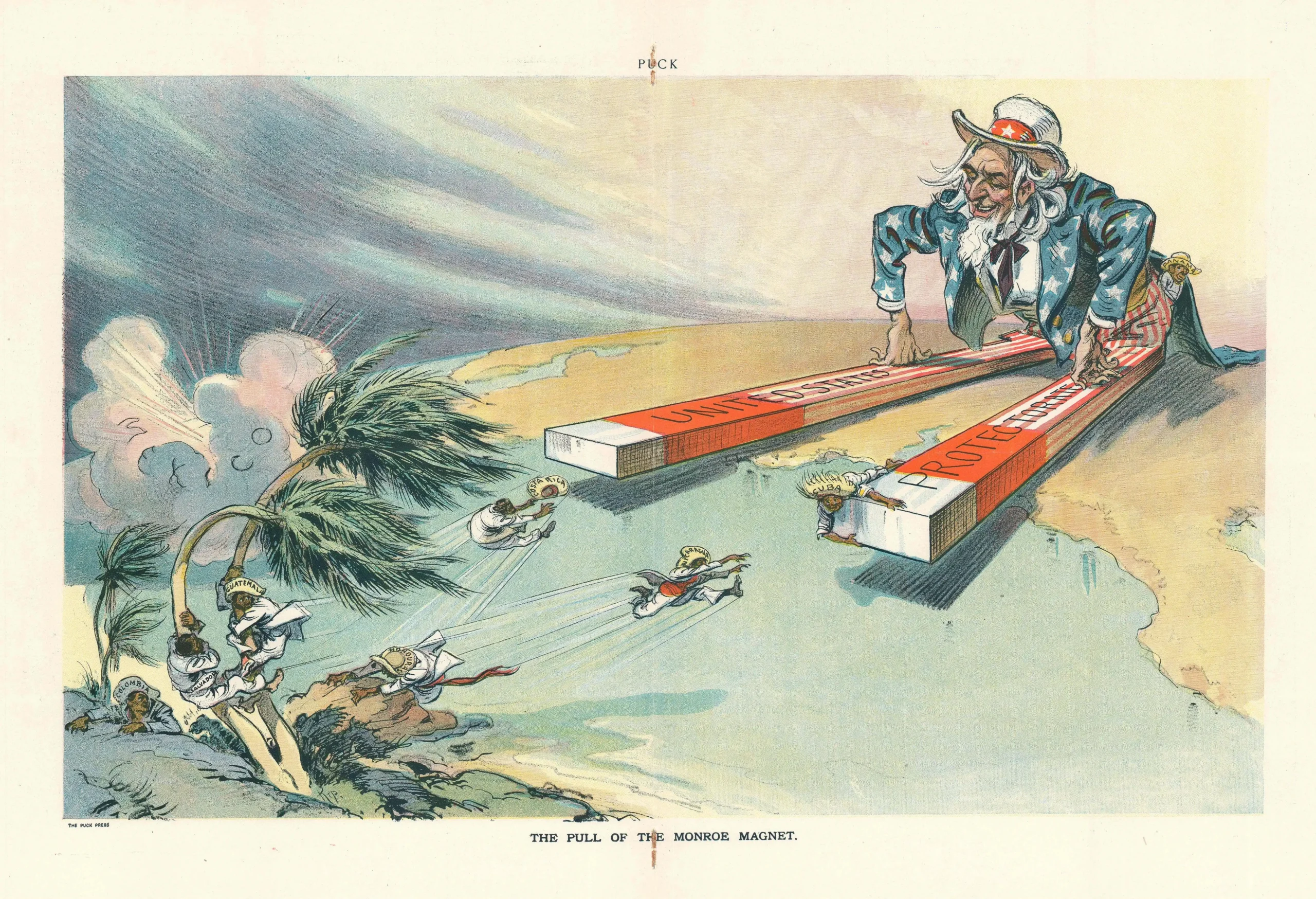

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now -

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day -

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy -

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it