The many lives of Professor Michael Atar

Dr Stephen Simpson

- Published

- Opinion & Analysis

From paediatric dentistry to sepsis technology, psychotherapy and social innovation, Professor Michael Atar has built a career that refuses to stay in one lane. The European’s Dr Stephen Simpson meets the man whose work spans medicine, physics, mental health and community life

Professor Michael Atar begins with a request most interviewers would dread: “Please interrupt me often.” He says it as soon as the call begins, explaining that tangents help him think. The instruction proves accurate. Within minutes, our conversation moves between fields that seldom meet in one career: sepsis diagnostics, early infant attachment, medical innovation, developmental difficulty, justice within institutions, and the practical consequences of business failure. He moves between them easily, with a method clearly shaped over decades.

He traces that method to the household in which he grew up. “My dad was an ophthalmic surgeon, and my mum a neonatal nurse. I learned so much from them,” he says. Their professional lives sat alongside an interest in music, creating an environment where technical skill and emotional awareness were present at the same time. Professor Atar talks about it without sentimentality. The combination of those influences, he says, gave him “a wide sense of not just being very focused on one trait but combining ideas, emotions all together.”

His professional life began in paediatric dentistry. A Swiss-born academic, Atar built his early reputation through clinical work, pioneering research and teaching, lecturing across Europe and the United States. He later held a professorship at New York University, where his clinical expertise and mentorship influenced younger practitioners. His scientific publications contributed to developments in paediatric dentistry and the standards that underpin it.

His curiosity for how science could expand the limits of clinical practice led him into biomedical physics, a field that connected his clinical experience with innovation. Applied physics offered a deeper understanding of biological structures, and medical imaging extended that work into the processes occurring within the body rather than only their outward expression. That transition marked the beginning of a new chapter in which he also became involved in the development of innovative medical technologies. As a venture capital investor and scientific adviser, he took on work aimed at bringing life-saving tools from concept to clinic.

Alongside this scientific and entrepreneurial trajectory, he developed a long-standing commitment to mental health. Trained as a psychoanalytic psychotherapist, he works with families, parents and children, drawing on twenty-five years of clinical experience to address trauma, attachment and developmental challenges. His focus on parent-infant psychotherapy stems from his conviction that early emotional attunement has long-term consequences. “A child who is seen and heard will grow into an adult who can care,” he tells me.

These strands — science, physics, psychology and clinical practice — shaped the way he approached the early biomedical start-ups he encountered. Sepsis, with its speed, unpredictability and high mortality rate, held particular urgency. He recognised that faster diagnosis required new technologies as well as adjustments to existing methods. That awareness formed part of the perspective he carried when he first spent sustained time in Silicon Valley. There, he encountered scientists, technologists and founders across fields he had not anticipated understanding. “I suddenly realised, with my background of medicine and dentistry and applied physics into imaging, that I understand this,” he says. The scale of the work was immediately apparent. “It was really the ignition. I knew where they are going, and I wanted in.”

Within that environment he became involved with Cytovale, the San Francisco-based diagnostics company pioneering the rapid detection of sepsis. As lead investor and adviser, he supported the decade-long development of IntelliSep, an FDA-approved test able to identify sepsis from a standard blood sample in under ten minutes with 97% accuracy. The work required over US$120 million and more than ten years. Its potential use in settings such as NHS hospitals forms part of its significance.

His portfolio later extended beyond diagnostics to digital health innovation. With Remedly, a company focused on healthcare data integration and recently voted Best Revenue Cycle Management Software 2025, he has worked on efforts to strengthen secure, patient-centred information sharing between doctors, hospitals and insurers — an area often described as a missing link in modern healthcare. His investment philosophy reflects the combination of due diligence, scientific understanding and ethical considerations that he brings to such work.

More recently, his broader commitment to human connection shaped NEER, his social-technology initiative aimed at addressing loneliness, social anxiety and isolation. Developed through his company NEER Global, the platform encourages safe, meaningful in-person interaction rather than superficial online exchanges. It partners with venues to establish verified “safe spots” for users and rewards genuine social engagement. Its London launch earlier this year drew attention from public figures including Ukrainian dance celebrity Nadiya Bychkova, who praised its focus on real conversation over digital distraction. Expansion to New York, the Middle East and Mumbai is underway. For Atar, NEER continues the same philosophy that links his work in healthcare, psychology and community life: using science and empathy to rebuild human connection.

His engagement with community extends beyond professional work. In Britain, for instance, he has supported education, welfare and youth development within the Jewish community. He has funded scholarships and community projects, and he donated a major new building to Immanuel College in Bushey, Hertfordshire. He also contributed to shaping the project’s purpose. The facility expands opportunities for study, creativity and community engagement, reflecting the values he considers central: intellectual curiosity, compassion and responsibility.

Atar’s experience in Silicon Valley reinforced two lessons. “We can branch out and we can look at the bigger picture,” he says. But it also highlighted the boundaries of knowledge. “Be very aware of what your knowledge is.” These principles shaped the choices he made in technology and the ventures he declined.

There was one exception. He describes the biggest failure of his career with care, stressing that he does not want it sensationalised. He attempted to enter the hotel business, bought a property in the south of France, and found himself surrounded by people whose interests did not align with his own. “Everything went wrong,” he says with sincerity. The property was magnificent, the view extraordinary, yet the venture collapsed. It taught him that charm, optimism and intellect do not overcome structural realities or unsuitable partnerships. “Sometimes things go wrong because we’re human beings,” he explains. The experience led to a firm conclusion: “I’m never touching a hotel again. Sometimes it’s great to acknowledge that a dream is allowed to stay a dream.”

When he speaks about intuition, he describes it in clinical terms. “Our visceral nerve system is almost like a second brain,” he says. When something feels wrong, he believes the body is signalling. When he ignored those signals, consequences followed. When he listened, outcomes aligned. “Very often the results were pretty much aligned to my gut feeling.” He applies this to people as well. Some impressed him intellectually while being doubtful internally. Time confirmed the instinct.

In psychotherapy, he says, the first session often contains the essence of what will follow. It is a pattern he has observed across decades. Yet he is cautious about transferring this to business. He has taken risks that worked and those that failed. He has seen the “halo and horns effect”: the tendency to favour those who resemble us and resist those who do not. He quotes a line he once heard — “hire slow and fire fast” — but moves past it quickly. Unlike many at the top of their game, Atar still believes in “second and third chances”.

His working habits are straightforward. He clears the space around him before he begins. “I can think most clearly when my surroundings are in order,” he says. He pays limited attention to professional critique from acquaintances, having learnt that motives can be mixed. He trusts his children more. “Their feedback is often brutal but rarely wrong and never carries an agenda,” he says.

Asked about misconceptions surrounding high performance, he lists several. The first is the idea of being self-made. “We are all dependent and interdependent,” he answers. The second is that success comes solely from knowledge or will; he sees luck or providence as a more accurate factor. The third is the belief that successful people are emotionally impenetrable. “Sometimes somebody comes across as very self-confident, very successful, but that doesn’t mean it looks the same inside that person.” The fourth is brief: “Don’t be that humble. You’re not that important.”

The role he names most readily is fatherhood. “Being a dad,” he says. His greatest wish takes longer to articulate. Eventually he defines it as seeing those around him “satisfied… without pain and without struggles.” What troubles him is recognising that he cannot always help. “Sometimes even very close people have struggles which I can’t solve for them,” he says. The feeling, he adds, is “helplessness in its truest form.”

As the interview draws to a natural close, I ask him what he most wants others to have. He answers without hesitation: “Health and meaning.” He explains that health gives people the stability to live, and meaning gives them the reason to keep going. “If you have those two,” he says, “you can navigate almost anything.”

While he speaks, I explain the background on my Zoom screen: a blue-white image of Earth seen from orbit. It was there throughout the call, but only now, as he talks about perspective and purpose, does it draw his attention. He turns to look at it for a moment. “You know,” he says, “that picture… it reminds me how small we are, and how much we still have to care for each other.”

Dr. Stephen Simpson is an internationally acclaimed mind coach, TV and radio presenter, hypnotherapist, TEDx speaker, bestselling author, business consultant, and Fellow of the Royal Society of Medicine. With nearly 40 years as a practicing physician and extensive experience in elite performance coaching, mental health, hypnosis, and NLP, he has worked with top athletes on the PGA European Golf and World Poker Tours. Dr. Simpson holds an MBA from Brunel University and has served as Regional Medical Director for Chevron, contributing to global health initiatives with leaders like Bill Clinton and Bill Gates. He hosts popular shows such as Zen and the Art of NLP, and his YouTube channel boasts over 260 videos and 350,000 views. His latest book, The Psychoic Revolution, encapsulates his innovative methods for achieving peak performance.

READ MORE: ‘Surgeons just changed medicine forever using hotel internet connection‘. Groundbreaking surgery carried out over a hotel internet connection could change medicine forever. Consultant surgeon Prasad Patki tells The European’s Dr Stephen Simpson, himself a former medical doctor with decades of frontline experience, why robotics, telesurgery, and AI are set to redraw the map of global healthcare.

Do you have news to share or expertise to contribute? The European welcomes insights from business leaders and sector specialists. Get in touch with our editorial team to find out more.

Main image: Supplied

RECENT ARTICLES

-

Europe cannot call itself ‘equal’ while disabled citizens are still fighting for access

Europe cannot call itself ‘equal’ while disabled citizens are still fighting for access -

Is Europe regulating the future or forgetting to build it? The hidden flaw in digital sovereignty

Is Europe regulating the future or forgetting to build it? The hidden flaw in digital sovereignty -

The era of easy markets is ending — here are the risks investors can no longer ignore

The era of easy markets is ending — here are the risks investors can no longer ignore -

Is testosterone the new performance hack for executives?

Is testosterone the new performance hack for executives? -

Can we regulate reality? AI, sovereignty and the battle over what counts as real

Can we regulate reality? AI, sovereignty and the battle over what counts as real -

NATO gears up for conflict as transatlantic strains grow

NATO gears up for conflict as transatlantic strains grow -

Facial recognition is leaving the US border — and we should be concerned

Facial recognition is leaving the US border — and we should be concerned -

Wheelchair design is stuck in the past — and disabled people are paying the price

Wheelchair design is stuck in the past — and disabled people are paying the price -

Why Europe still needs America

Why Europe still needs America -

Why Europe’s finance apps must start borrowing from each other’s playbooks

Why Europe’s finance apps must start borrowing from each other’s playbooks -

Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes

Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes -

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others -

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again -

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart?

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart? -

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing -

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage -

The limits of good intentions in public policy

The limits of good intentions in public policy -

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament?

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament? -

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth -

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours -

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality -

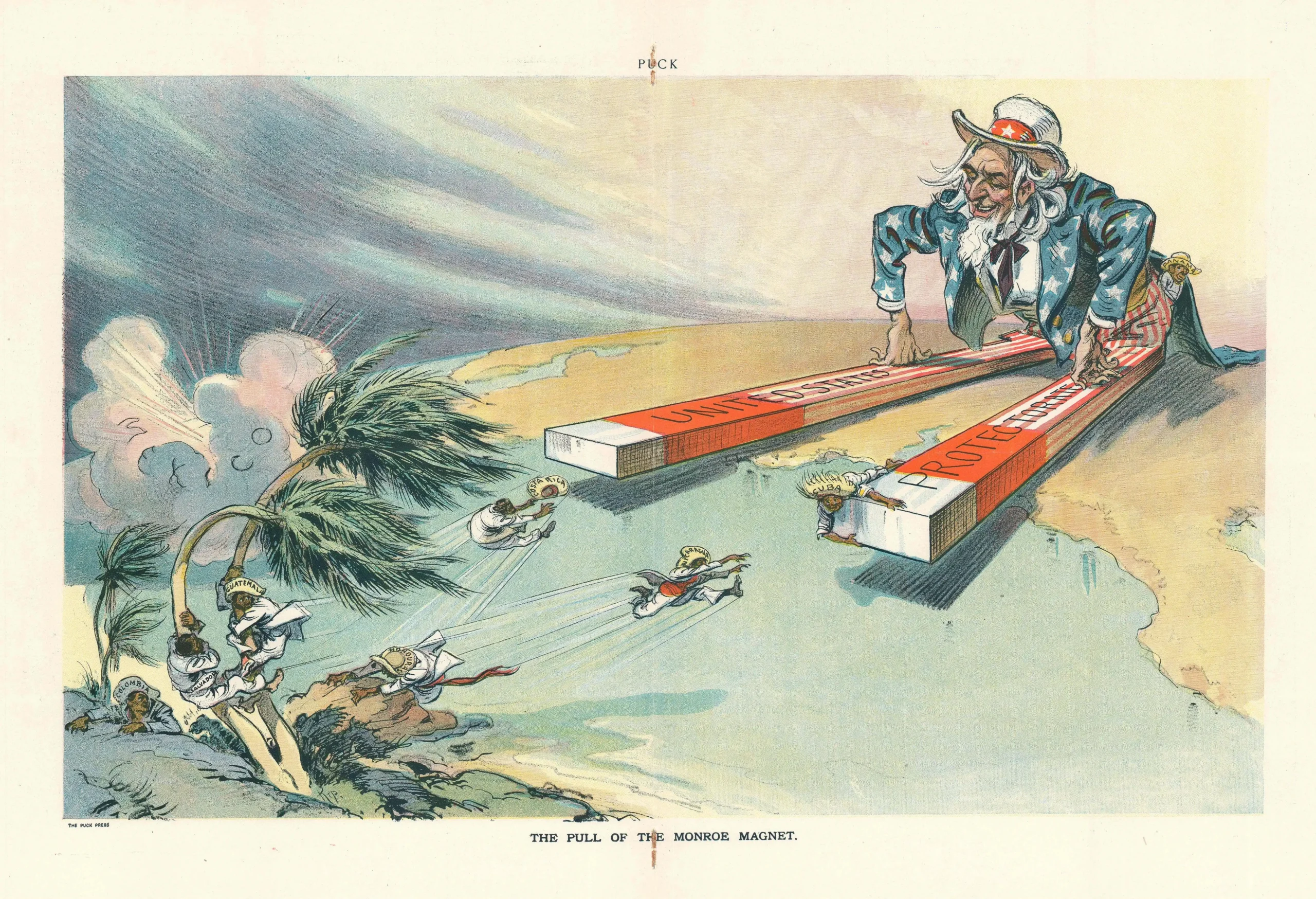

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now -

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day -

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy -

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it