Surgeons just changed medicine forever using hotel internet connection

Dr Stephen Simpson

- Published

- Technology

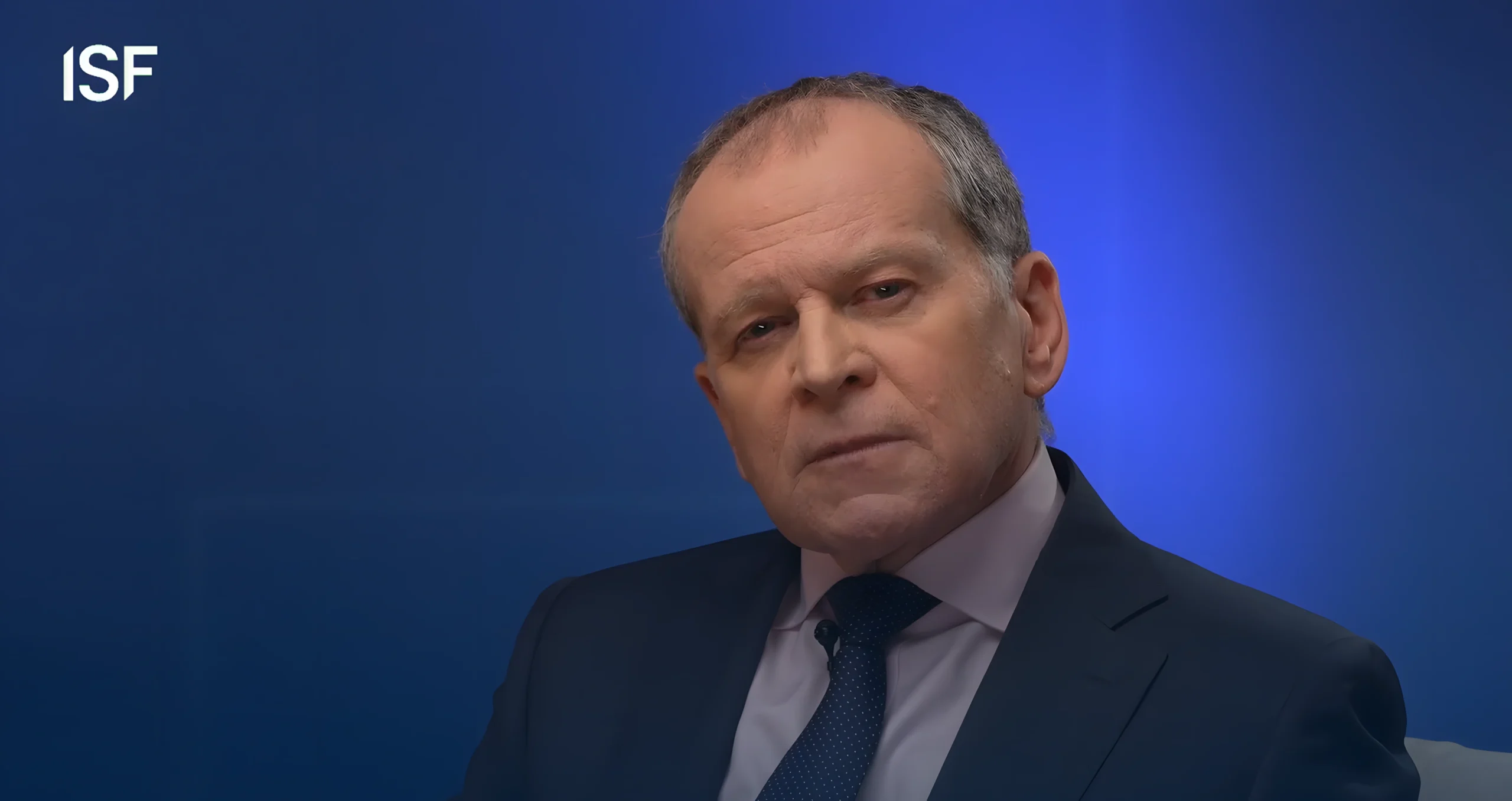

Groundbreaking surgery carried out over a hotel internet connection could change medicine forever. Consultant surgeon Prasad Patki tells The European’s Dr Stephen Simpson, himself a former medical doctor with decades of frontline experience, why robotics, telesurgery, and AI are set to redraw the map of global healthcare

Not long ago, a small team of specialist surgeons gathered in a central London hotel. Dressed in everyday clothes, they sat on stools and took control of their respective consoles. On the robot consoles before them lay their patients, prostrate under anaesthetic in operating theatres many hundreds, and in some cases thousands, of miles away.

One worked on a man undergoing a partial nephrectomy in Beijing. Another on a patient in Belgium also needing a partial nephrectomy, in which part of the kidney is removed.

The consultants used the delicate controls at their fingertips to guide robotic arms that mimicked their movements almost instantly. The response time was just 22 to 26 milliseconds, a speed so fast that the difference between action in London and effect in the operating theatre abroad was barely perceptible.

Telesurgery, operations performed through robotic systems, is not new. In 2001, surgeons in New York carried out the first such procedure, removing a gallbladder from a patient in Strasbourg in what became known as the “Lindbergh Operation.” Since then, the technique has steadily advanced and spread, with cases reported across various age groups and geographic regions. Only this September, a consultant in Gurugram used the technology to perform kidney surgery on a 16-month-old baby in Hyderabad, 1,600 kilometres away — the youngest telesurgery patient in the world.

But the demonstration by the European Robotic Urological Surgeons Association in London was groundbreaking because the operations were carried out over a hotel network connection. Over three days, surgeons performed 36 operations in four hospitals using six different robotic platforms.

For Prasad Patki, a consultant urological surgeon who leads the Robotic Urological Surgery Programme at Barts Hospital, it marked what could be the beginning of a new era in how surgical expertise is delivered across borders.

Within a decade, patients could have access to the best surgeons in the world, no matter where they live and regardless of the robotic expertise available in their local hospital. It may not even matter where the surgeon themselves are, so long as the hospital has the right robotic system on site and a trained team ready to support the procedure and handle complications.

“In time, we won’t be talking about a handful of procedures and demonstrations like this one but a network where expertise flows globally. In ten or fifteen years, I expect it will be routine for a surgeon in one continent to operate on a patient in another. It will change the very definition of what a hospital is.”

At its core, telesurgery is a marriage of robotics, imaging, and high-speed connectivity. A surgeon sits at a console, often far from the patient, and uses hand and foot controls to manipulate robotic instruments. A 3D camera provides magnified, high-definition views of the operative field, allowing movements made in one room to be replicated with precision in another.

The principle is simple but the execution is highly technical. Every command, from a fingertip adjustment to a change in pressure, must be transmitted across a digital network and reproduced by the robot without delay or distortion. Even a fraction of a second in lag can disrupt the fine motor control needed for delicate procedures, which is why latency and stability are critical.

At the patient end, a robotic platform, typically equipped with multiple articulated arms, carries out the surgeon’s instructions. One arm may hold the camera, while others manipulate instruments such as forceps, scissors, or cauterising tools. The system scales and filters the surgeon’s hand movements, removing tremor and enabling ultra-fine motions that would be difficult to achieve unaided. A trained theatre team remains in place beside the patient, positioning instruments, managing anaesthesia, and standing ready to intervene if required.

Over the past two decades, robotic systems have become increasingly common in operating theatres for procedures ranging from prostatectomies to gynaecological and cardiac surgery, with remote operations typically lasting between one and five hours or more. Telesurgery extends that capability by removing the geographical tether between surgeon and patient.

But while telesurgery dominates the headlines, the vast majority of robotic procedures today are still performed with the surgeon in the same room as the patient. In these cases, the console sits only a few feet from the operating table, but the advantages are identical: smaller wounds, less pain, faster recovery, and less physical strain on the surgeon.

In practical terms, it is keyhole surgery taken several steps further.

“Traditional laparoscopic instruments are rigid and awkward, whereas robots translate the surgeon’s natural hand movements into precise, wristed actions deep inside the body,” Prasad explains.

“We are now doing procedures as day cases that ten years ago required a week in hospital. That was unthinkable then. A kidney removal, as one example, can now be performed in the morning with patients discharged by evening.”

For surgeons, the benefits are just as clear. Prasad describes the immersive 3D view, magnified tenfold, as a revelation. “I have a better view than I would with the naked eye. Even if you have shakes in your hand, the robot will scale them down. That is very reassuring, particularly as we get older.”

Sitting at a console rather than standing at an operating table also reduces strain. The result, he says, is not only safer surgery but longer surgical careers.

Surgical training everywhere has been reshaped by simulation, but nowhere more so than in robotics. The old mantra of “watch one, do one, teach one” no longer fits when surgery is performed through a console rather than at the bedside.

Today, trainees can rehearse operations in high-fidelity simulators, practice on tissue models, and share control with mentors at dual consoles. The result is a system in which skills can be acquired and tested long before a surgeon performs a procedure on a patient.

“You can now rehearse an operation in a high-fidelity environment before you ever touch a person,” Prasad explains. Advances in imaging mean 3D reconstructions from CT or MRI scans can be overlaid on tissue models, allowing a surgeon to practise navigating around vessels that are specific to that patient.

In the UK, where operating on live animals is prohibited, trainees use tissue blocks – a pig bladder with its urethra, or a kidney with surrounding structures – to get a sense of real biological resistance. From there, they progress to mentored human cases. Dual consoles, where trainer and trainee can share control of the robot, make the handover smoother. “The transfer of skills is seamless,” he tells me. “It has completely transformed training.”

Just as pilots train in flight simulators for engine failure or nuclear staff rehearse power outages, surgical teams now rely on technology to practise rare but high-risk emergencies in simulation. A sudden haemorrhage, a cardiac arrest, or the need to switch rapidly from robotic to open surgery can all be created in a controlled environment. The aim is to condition teams to respond instinctively when those events occur for real.

“You can create a cardiac arrest in the middle of the case, or a severe bleed, and practise your response. That kind of rehearsal has already proven to be a lifesaver.”

The next frontier, Prasad believes, is the integration of AI. Robots already act as stabilisers and amplifiers of human skill but artificial intelligence could add decision support to the mix.

“There are lots of tasks which are repetitive and can be handed over,” he says. “And there are lots of areas where AI and humans can operate simultaneously, focusing on their respective specialist sets.”

He imagines a future in which the robot proposes a route through tissue based on pre-operative scans, leaving the surgeon to decide whether to follow it. Even suturing may one day be automated: “You could leave a bot to put in 14 skin sutures while you have a coffee,” he jokes.

Touch, however, is still missing. Current systems do not provide haptic feedback, leaving surgeons to judge tension by sight alone.

“When you tie a knot with a very fine stitch you must use minimal tension, with a larger suture more force is possible,” he explains. “At present we judge that by how the knot looks, not how it feels.” New models are beginning to restore that sense, but he has yet to try them himself.

Cost is another barrier, though one he believes is temporary. Early dominance by a single manufacturer made robotic systems prohibitively expensive and created a postcode lottery in access. Competition is now bringing down prices.

“It will be the same as laparoscopic gallbladder surgery. At first it was done only in niche units. Now it is routine in county hospitals as a day case. Robotics will follow the same path.”

The bigger challenge, he argues, is cultural and organisational: how hospitals train teams, how they govern safety, how they share data. Every movement in a robotic operation is recorded. That allows surgeons to benchmark themselves against European averages and against the top ten per cent of high-volume operators. Within trusts, colleagues can review each other’s videos and learn directly. The potential is enormous, but so are the ethical questions.

“Medicine has always advanced by sharing. We can anonymise data and use it for teaching. Patients must give consent, and we must protect their information. But we should not over-regulate, because that will slow progress.”

Responsibility, he insists, cannot be outsourced. Even as robots become more autonomous, it is the surgeon who remains accountable.

“It will always be the responsibility of the surgeon. You just can’t hide from that.” Any move toward autonomy must meet the highest technical standards. Everyday IT failures, the frozen screens and reboot cycles familiar to everyone, are not acceptable in theatre.

“We can’t do that in surgery. Precision must be at the highest level before autonomy is safe.”

That caution extends to training the next generation. With robotic procedures now becoming the norm in major hospitals, younger surgeons risk losing the ability to perform open operations when they are truly needed.

“Certain conditions still require open surgery,” he warns. “My generation was probably the last to get dedicated open surgical training as well as new technology. We must preserve those skills.”

Prasad’s perspective is shaped as much by history as by the latest innovation. He grew up in India in a family of surgeons. His grandfather practised; his father was a prolific general surgeon who ran a hospital of his own. As a boy, Prasad would stand at the edge of the theatre, sometimes even assisting.

“That would be unthinkable now,” he says. “But at that time it was possible.” Medicine, in other words, was both inheritance and environment.

He admits it was not inevitable. Weakness in mathematics pushed him towards medicine when other scientific routes closed, but surgery felt natural. He trained in general surgery before turning to urology, attracted by the specialty’s eagerness to adopt technology. Patients who once endured week-long stays after open procedures were being discharged the same day.

“That was fascinating,” he recalls. Mentors shaped the rest. In Pune, Professor Deepak Kirpeker taught him both surgical technique and the art of speaking to patients in difficult circumstances. In London, working under Mr Julian Shah at UCL, he absorbed evidence-based thinking that balanced his instinctive, hands-on approach. And then came Mr Damian Hanbury at Stevenage, who nudged him away from reconstructive surgery just as laparoscopy and robotics were emerging. “Everything changed. The ball just kept rolling.”

The hardest case he recalls is not a cancer but an infection: a morbidly obese patient with an obstructed kidney that had endured multiple failed procedures. He and a colleague alternated at the console for seven and a half hours.

“Sharing a problem goes a long way to solve a difficult problem,” he says. “A two-consultant approach gives the patient the maximum benefits.”

Asked what he teaches that a textbook cannot, he is direct:

“Safety first. Treat the tissue with respect and it reciprocates by healing faster. Speed is not haste but speed is going slow with determination and precision and efficiency.”

Balance, he says, comes from home. His wife, a dentist, is his confidante and sounding board. His son, now also a doctor, and daughter, working in media management, have heard the advice he passes on: keep a hobby, play an instrument, run, exercise, sleep.

“A pat on the back goes a long way. A hug goes a long way.” Family, he believes, accounts for most of his success.

Even after years at the cutting edge, he is energised rather than jaded about what’s to come with technology.

“We’ve moved beyond science fiction,” he says with quiet certainty. “The future is already here.”

As our conversation draws to a close, I ask him what his father, the prolific general surgeon who first let a young boy stand at the edge of the operating theatre in India, would have made of this new world of robotics, AI, and telesurgery.

Prasad pauses, then smiles.

“He would have been fascinated. My father was always curious, always ready to try new things if they could help his patients. He would have said, ‘This is the way forward, but never forget the basics.’ That’s what he would remind me. Technology will change, but the principles of surgery will not.”

Dr. Stephen Simpson is an internationally acclaimed mind coach, TV and radio presenter, hypnotherapist, TEDx speaker, bestselling author, business consultant, and Fellow of the Royal Society of Medicine. With nearly 40 years as a practicing physician and extensive experience in elite performance coaching, mental health, hypnosis, and NLP, he has worked with top athletes on the PGA European Golf and World Poker Tours. Dr. Simpson holds an MBA from Brunel University and has served as Regional Medical Director for Chevron, contributing to global health initiatives with leaders like Bill Clinton and Bill Gates. He hosts popular shows such as Zen and the Art of NLP, and his YouTube channel boasts over 260 videos and 350,000 views. His latest book, The Psychoic Revolution, encapsulates his innovative methods for achieving peak performance.

READ MORE: ‘Paul McKenna wants to change how Britain thinks about mental health‘. Since the early 1990s, Paul McKenna has been the world’s most recognisable hypnotist with a reputation for rapid personal change. But what many people don’t know is that behind the public profile, he has spent decades working at the front line of mental health to help survivors of trauma, addiction and burnout rebuild their lives. Now, as the UK faces what he calls a new psychological emergency, McKenna is calling for a fundamental rethink of how we teach resilience. In this exclusive and wide-ranging interview with The European’s Dr Stephen Simpson, he reflects on collapse, recovery, and why emotional wellbeing should be part of every child’s education.

Do you have news to share or expertise to contribute? The European welcomes insights from business leaders and sector specialists. Get in touch with our editorial team to find out more.

Main Image: Prasad Patki (second left) with colleagues from the Robotic Urological Surgery Programme at the Royal Free Hospital. © Supplied

RECENT ARTICLES

-

Deepfake celebrity ads drive new wave of investment scams

Deepfake celebrity ads drive new wave of investment scams -

Europe eyes Australia-style social media crackdown for children

Europe eyes Australia-style social media crackdown for children -

Europe opens NanoIC pilot line to design the computer chips of the 2030s

Europe opens NanoIC pilot line to design the computer chips of the 2030s -

Building the materials of tomorrow one atom at a time: fiction or reality?

Building the materials of tomorrow one atom at a time: fiction or reality? -

Universe ‘should be thicker than this’, say scientists after biggest sky survey ever

Universe ‘should be thicker than this’, say scientists after biggest sky survey ever -

Lasers finally unlock mystery of Charles Darwin’s specimen jars

Lasers finally unlock mystery of Charles Darwin’s specimen jars -

Women, science and the price of integrity

Women, science and the price of integrity -

Meet the AI-powered robot that can sort, load and run your laundry on its own

Meet the AI-powered robot that can sort, load and run your laundry on its own -

UK organisations still falling short on GDPR compliance, benchmark report finds

UK organisations still falling short on GDPR compliance, benchmark report finds -

A practical playbook for securing mission-critical information

A practical playbook for securing mission-critical information -

Cracking open the black box: why AI-powered cybersecurity still needs human eyes

Cracking open the black box: why AI-powered cybersecurity still needs human eyes -

Tech addiction: the hidden cybersecurity threat

Tech addiction: the hidden cybersecurity threat -

Parliament invites cyber experts to give evidence on new UK cyber security bill

Parliament invites cyber experts to give evidence on new UK cyber security bill -

ISF warns geopolitics will be the defining cybersecurity risk of 2026

ISF warns geopolitics will be the defining cybersecurity risk of 2026 -

AI boom triggers new wave of data-centre investment across Europe

AI boom triggers new wave of data-centre investment across Europe -

Make boards legally liable for cyber attacks, security chief warns

Make boards legally liable for cyber attacks, security chief warns -

AI innovation linked to a shrinking share of income for European workers

AI innovation linked to a shrinking share of income for European workers -

Europe emphasises AI governance as North America moves faster towards autonomy, Digitate research shows

Europe emphasises AI governance as North America moves faster towards autonomy, Digitate research shows -

Surgeons just changed medicine forever using hotel internet connection

Surgeons just changed medicine forever using hotel internet connection -

Curium’s expansion into transformative therapy offers fresh hope against cancer

Curium’s expansion into transformative therapy offers fresh hope against cancer -

What to consider before going all in on AI-driven email security

What to consider before going all in on AI-driven email security -

GrayMatter Robotics opens 100,000-sq-ft AI robotics innovation centre in California

GrayMatter Robotics opens 100,000-sq-ft AI robotics innovation centre in California -

The silent deal-killer: why cyber due diligence is non-negotiable in M&As

The silent deal-killer: why cyber due diligence is non-negotiable in M&As -

South African students develop tech concept to tackle hunger using AI and blockchain

South African students develop tech concept to tackle hunger using AI and blockchain -

Automation breakthrough reduces ambulance delays and saves NHS £800,000 a year

Automation breakthrough reduces ambulance delays and saves NHS £800,000 a year