Life’s lottery and the economics of poverty

Harry Margulies

- Published

- Opinion & Analysis

A child’s prospects can depend heavily on the country they are born into and the support it provides. Harry Margulies examines how these early “wins” and “losses” affect opportunity later in life

The desire to elevate one’s own economic position — and to secure better prospects for one’s children — is a natural and deeply rooted human motivation. Outcomes in life are, however, shaped far more by circumstances than many are willing to admit. Those born in the right country, to supportive parents, and blessed with good health, intelligence, favourable personal traits or exceptional abilities in fields such as sport, business or academia are, in effect, the winners of life’s lottery.

An uncomfortable truth often overlooked is that no one succeeds purely because of their own efforts. We know this because if effort alone determined success, the poorest countries would be full of millionaires.

When we hear a millionaire in the West declare, “I did it all by myself”, they might want to ask whether the same effort would have produced the same result in Yemen, Haiti, or any country plagued by conflict, weak institutions, and social collapse. Success in the West rests on foundations built before individual efforts even enter the picture: infrastructure, secure property rights, rule of law, public education and functioning markets.

Biological and social constraints matter, too. Intelligence, health, and psychological resilience are unevenly distributed at birth. If low cognitive ability is compounded by addiction, chronic illness, or other disabilities, individuals may find themselves relying on the very bottom of their society’s safety net— if such a net exists, that is. The very poor historically relied on large families as their safety net.

Historically, and still in parts of the developing world, families have had many children out of necessity. High child mortality and the absence of state support made large households a form of insurance in old age. The expansion of education, healthcare and pension systems altered this dynamic in modern societies. These institutions did not remove inequality, yet they reduced the harsh reliance on luck, survival and fertility. Large families with limited resources could trap parents and children in generational poverty.

Poverty can be seen as a set of circumstances that limit someone’s ability to meet basic needs, have real choices and improve their lives. But it’s important to distinguish between relative and absolute poverty.

Absolute poverty refers to the condition in which individuals lack the resources to meet basic human needs such as sufficient food, clean water, shelter and clothing. Access to primary healthcare and basic education also belongs in this category: without the ability to read or undertake simple arithmetic, the prospects of working one’s way out of poverty are sharply limited. The World Bank defines “extreme poverty” as living on less than US $2.15 per day on a purchasing-power-parity (PPP) basis. PPP adjusts for the local cost of a standardised basket of goods, translating what US$2.15 buys in the United States into the equivalent amount in other currencies. A playful illustration of PPP is The Economist’s annual “Big Mac Index”, which compares the dollar price of a Big Mac across countries to highlight differences in local purchasing power.

Relative poverty, by contrast, measures poverty against the prevailing standard of living within a particular society. Individuals in relative poverty fall far below the societal norm, which limits their ability to participate fully in economic and cultural life. It creates real pressures, but it differs fundamentally from deprivation. If you belong to a low-income household in North America or Western Europe, for instance, you may struggle economically but you still have access to public education, reasonable healthcare, social safety nets, legal protections and infrastructure that far exceed what middle-class families in impoverished countries can rely on.

Relative poverty can produce social tension and even unrest when large parts of the population feel excluded from the mainstream. Absolute poverty, by comparison, is strongly influenced by geography, particularly where climate, resources and infrastructure constrain economic development.

Absolute poverty is concentrated in regions such as sub-Saharan Africa, parts of South Asia and Yemen. In such environments, people may spend their days searching for water and food, and may also have to navigate corruption, for example by paying those who control a well. Under these conditions the prospects of escaping what often becomes multi-generational poverty are slim. For those with intelligence and ambition, pervasive corruption can create its own perverse incentives, encouraging participation in the oppressive system rather than attempting to succeed against overwhelming odds.

There are, fortunately, positive lessons to draw. Ethiopia and Rwanda have both introduced programmes that offer predictable support to households. These programmes “insure” against shocks such as drought, illness and food-price spikes, so that families no longer need to sell livestock, skip meals or withdraw children from school. The security of knowing they will not fall further into poverty encourages a degree of risk-taking. Because these systems operate nationwide, deliver reliable benefits and persist across political cycles, donors have been able to sustain their contributions. Good governance is central to their success.

Increasing aid to the poorest is not automatically a solution. Direct cash transfers can generate inflation if the supply of goods is limited, and there is always the risk that corrupt leadership diverts funds. Where elements of a functioning society exist, microloans — most often extended to women — have shown some promise. If recipients can begin weaving or basket-making, turn that activity into a small business and be left to pursue it, the rudiments of economic development can emerge.

When I studied international economics at university, one of my professors — who advised several African governments — put the matter succinctly. Aid, he argued, should be delivered in forms that employ the greatest number of people, thereby generating incomes, purchasing power and secondary economic activity. Faced with a choice between establishing a factory that one engineer could operate with modern technology, or one that employs five thousand workers at low wages, the latter would be preferable in such settings. Western economies passed through comparable stages of development, and the process cannot always be accelerated.

Some individuals lack the skills needed for economic success and, in affluent countries, rely on the social safety nets available to them. Others have the skills but experience transitional poverty: a person who loses their job and lives on unemployment insurance (where available) is generally expected to return to work. Recessions and depressions can shift poverty from relative to absolute. Many argue that the answer lies in taxing the rich more heavily, although high taxation may reduce incentives to invest and produce, both of which generate employment and reduce poverty.

Individual responsibility should not be dismissed. The moral lesson is not that effort is irrelevant, but that it is insufficient. Functioning societies are collective achievements. A fair society does not pretend that everyone starts from the same position; rather, it recognises the role of luck for the fortunate and works to ensure that failure is not a life sentence imposed at birth.

Harry Margulies is a journalist, author, commentator, and public intellectual whose work interrogates religion, politics, and morality with sharp wit and fearless clarity. A second-generation Holocaust survivor, he was born in Austria and spent time in an Austrian refugee camp before moving to Sweden. Educated by Orthodox rabbis throughout his childhood, he ultimately abandoned faith in his teens—a journey that has shaped his lifelong commitment to secularism, critical thinking, and freedom of expression. His latest book, Is God Real? Hell Knows, has been described by ABBA’s Björn Ulvaeus as “funny, sharp, and unafraid.”

READ MORE: ‘In defence of a consumer-led economy’. Long-term prosperity lies in open markets, technological progress and global competition, not in the preservation of declining jobs, writes Harry Margulies. Governments should channel resources into retraining and adaptation rather than protectionism.

Do you have news to share or expertise to contribute? The European welcomes insights from business leaders and sector specialists. Get in touch with our editorial team to find out more.

Main image: Rafijul Momin/Pexels

RECENT ARTICLES

-

Europe cannot call itself ‘equal’ while disabled citizens are still fighting for access

Europe cannot call itself ‘equal’ while disabled citizens are still fighting for access -

Is Europe regulating the future or forgetting to build it? The hidden flaw in digital sovereignty

Is Europe regulating the future or forgetting to build it? The hidden flaw in digital sovereignty -

The era of easy markets is ending — here are the risks investors can no longer ignore

The era of easy markets is ending — here are the risks investors can no longer ignore -

Is testosterone the new performance hack for executives?

Is testosterone the new performance hack for executives? -

Can we regulate reality? AI, sovereignty and the battle over what counts as real

Can we regulate reality? AI, sovereignty and the battle over what counts as real -

NATO gears up for conflict as transatlantic strains grow

NATO gears up for conflict as transatlantic strains grow -

Facial recognition is leaving the US border — and we should be concerned

Facial recognition is leaving the US border — and we should be concerned -

Wheelchair design is stuck in the past — and disabled people are paying the price

Wheelchair design is stuck in the past — and disabled people are paying the price -

Why Europe still needs America

Why Europe still needs America -

Why Europe’s finance apps must start borrowing from each other’s playbooks

Why Europe’s finance apps must start borrowing from each other’s playbooks -

Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes

Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes -

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others -

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again -

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart?

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart? -

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing -

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage -

The limits of good intentions in public policy

The limits of good intentions in public policy -

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament?

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament? -

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth -

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours -

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality -

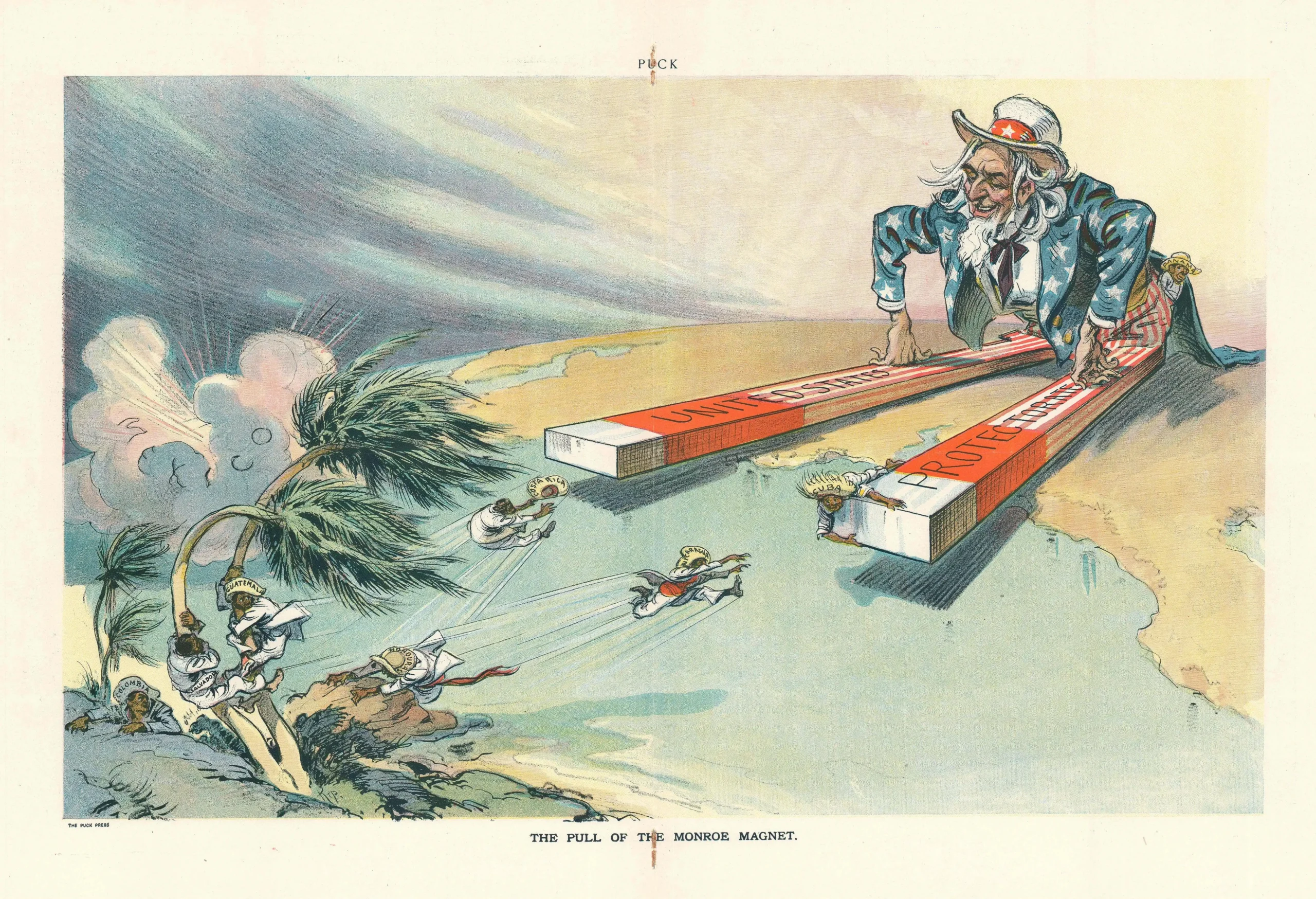

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now -

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day -

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy -

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it