This one digital glitch is pushing disabled people to breaking point

Matthew Kayne

- Published

- Opinion & Analysis

A timed-out form might be a nuisance for most, but for disabled users it wipes out hours of effort and blocks access to vital services. Matthew Kayne lays out how a small digital failure becomes a daily barrier to living independently

Filling in an online form is meant to be simple. For many, it is just another administrative task, part of the rhythm of life. But for a disabled person, particularly someone like me who uses assistive technology due to cerebral palsy, this ordinary task becomes an ordeal, a battle of patience, coordination, and emotional resilience. It is in these micro-moments—the ones that others overlook—that the daily reality of systemic inaccessibility is revealed.

Imagine this: you are slowly filling out a complex form for benefits, housing, or local council support. Every letter you type requires effort, sometimes aided by specialized keyboards or adaptive devices. You navigate dropdown menus, checkboxes, and text areas that are often poorly designed for screen readers or keyboard navigation. Each page is a careful calculation: how long will this take, can I sustain my focus, will my equipment respond correctly? You inch toward completion, aware that even the slightest error might reset the form.

Then, at the very last moment—after minutes, perhaps hours of painstaking work—the system logs you out. Every response, every carefully inputted detail vanishes. You are left staring at a blank page, drained, frustrated, and demoralized. Your energy, which was meticulously rationed to complete this task, has been wasted. Your motivation, which was hanging by a thread, takes a further hit. And the emotional toll is tangible: the sense that no matter how hard you try, the system is stacked against you.

This experience is not hypothetical. It is lived. Time after time, disabled people encounter forms that are fundamentally inaccessible, designed with assumptions that we can operate at the same speed as someone without a disability. The consequences are profound. It is not merely a matter of inconvenience. Each failed attempt represents lost opportunities: missed appointments, delayed support, increased anxiety, and the creeping realization that the system does not accommodate you, nor does it value your time or effort.

When I recount these experiences, it becomes clear that accessibility cannot be an afterthought—it must be embedded in every process, every interface, and every policy decision. Online forms are not just digital paper; they are gateways to rights, benefits, and dignity. And yet, they are often constructed as barriers.

Consider the compounding impact of repeated failures. Each time a form times out, the stakes rise. What was once a manageable task now becomes a source of chronic stress. Disabled people are forced to allocate additional hours to what should be routine activities, and the mental load is staggering. These micro-experiences accumulate, creating an invisible, constant struggle that is entirely absent from the public perception of disability.

But there is more than frustration at play here. These moments are a mirror reflecting broader systemic failures. When a form times out, it is not just the technology at fault. It is a system that expects disabled people to function within environments that are fundamentally incompatible with our needs. It is a society that values efficiency over equity, speed over accessibility. And it is a government that continues to promulgate policies without adequate input from those who experience them first-hand.

In many ways, this micro-experience captures the essence of the disabled experience in 2025. Every day is punctuated by small, often invisible barriers that accumulate into significant obstacles. The inability to complete a form efficiently is a stand-in for wider struggles: delays in equipment provision, inadequate social care, inaccessible transport, and bureaucratic hurdles that demand constant advocacy. Each minor frustration is a thread in a larger tapestry of exclusion.

Yet there is power in documenting and sharing these experiences. When a disabled person writes about the moment a form times out, it is not merely a complaint—it is evidence. It is a demonstration of how policies, systems, and societal assumptions fail. It is a way to say, “This is what independence looks like when it is denied, and these are the costs you cannot ignore.” By focusing on specific, tangible experiences, we provide an unvarnished look at the realities that policymakers often overlook.

Moreover, micro-experience pieces are vital because they humanize issues that might otherwise seem abstract. While statistics and broad policy discussions are important, they do not convey the lived reality. Telling the story of one form, one failed attempt, one frustrated moment, allows readers to empathize and understand the stakes in a visceral way. It is in these moments that advocacy gains power: it is no longer about abstract rights or distant policies; it is about real people navigating real systems.

Accessibility is not a luxury; it is a fundamental requirement for inclusion. When online forms fail disabled users, they undermine the very concept of equal access. Each timed-out form, each inaccessible interface, each unresponsive system is a reminder that disability is treated as an afterthought, a cost, or an inconvenience. And that is unacceptable.

As a journalist and a disabled person, I see these failures every day. I see the impact not only on myself but on millions of others who rely on these systems to maintain independence, access services, and live with dignity. By documenting and sharing these experiences, I aim to make invisible barriers visible. I aim to push policymakers, service providers, and society to recognize that every click, every keystroke, every failed form matters.

The challenge is enormous, but so too is the opportunity. By shining a light on micro-experiences, we can illuminate macro-problems. We can take what seems like a small inconvenience and show how it reflects broader inequities. We can challenge assumptions, demand accountability, and create momentum for meaningful change.

When the online form times out, it is more than technology failing—it is society failing. But telling the story is the first step toward change. And by sharing it publicly, we ensure that those with the power to change systems cannot claim ignorance.

For too long, disabled voices have been marginalized in conversations about policy and access. Micro-experiences like these are our evidence, our testimony, and our call to action. They are specific, relatable, and impossible to ignore. They demonstrate not only the failures of the system but also the resilience, determination, and creativity of disabled people navigating these barriers daily.

In conclusion, while the moment a form times out might seem trivial to an outside observer, it is emblematic of the systemic barriers that disabled people face. It is a lens through which we can examine how society, technology, and government treat disabled citizens. And it is a reminder that the fight for accessibility, dignity, and inclusion is not theoretical—it is lived, moment by moment, keystroke by keystroke, by people like me every single day.

Matthew Kayne is broadcaster, political campaigner and disability rights advocate who has turned personal challenges into platforms for change. He is the founder and owner of Sugar Kayne Radio, an online station dedicated to uplifting music and meaningful conversations, and the leader of a national petition calling for reform of the UK’s wheelchair service. Living with cerebral palsy and a survivor of bladder cancer, Matthew channels his lived experience into advocacy, broadcasting, and songwriting. His long-term ambition is to bring this experience into politics as an MP, championing disability rights, healthcare access, and workplace inclusion.

READ MORE: ‘Robots can’t care — and believing they can will break our health system‘. Artificial intelligence is being hailed as the next frontier in healthcare but as broadcaster and disability rights advocate Matthew Kayne writes, empathy cannot be automated. Real care exists in human presence, in the moments of understanding that only people can offer.

Do you have news to share or expertise to contribute? The European welcomes insights from business leaders and sector specialists. Get in touch with our editorial team to find out more.

Main image: RDNE Stock Project

RECENT ARTICLES

-

Why Europe still needs America

Why Europe still needs America -

Why Europe’s finance apps must start borrowing from each other’s playbooks

Why Europe’s finance apps must start borrowing from each other’s playbooks -

Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes

Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes -

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others -

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again -

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart?

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart? -

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing -

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage -

The limits of good intentions in public policy

The limits of good intentions in public policy -

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament?

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament? -

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth -

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours -

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality -

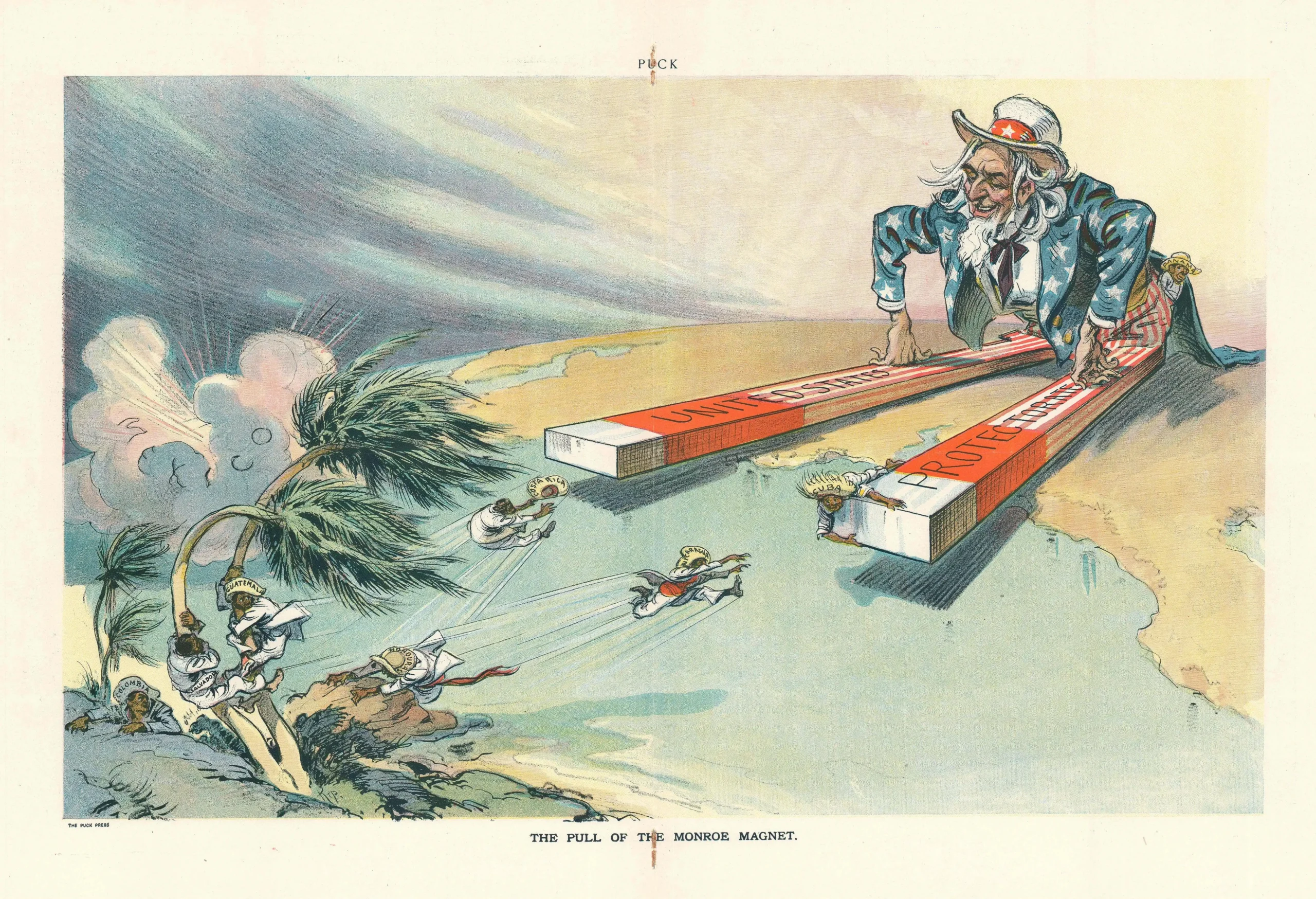

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now -

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day -

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy -

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it -

What if he falls?

What if he falls? -

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world -

Will Trump’s Davos speech still destroy NATO?

Will Trump’s Davos speech still destroy NATO? -

Philosophers cautioned against formalising human intuition. AI is trying to do exactly that

Philosophers cautioned against formalising human intuition. AI is trying to do exactly that -

Life’s lottery and the economics of poverty

Life’s lottery and the economics of poverty -

On a wing and a prayer: the reality of medical repatriation

On a wing and a prayer: the reality of medical repatriation -

Ai&E: the chatbot ‘GP’ has arrived — and it operates outside the law

Ai&E: the chatbot ‘GP’ has arrived — and it operates outside the law -

Keir Starmer, Wes Streeting and the Government’s silence: disabled people are still waiting

Keir Starmer, Wes Streeting and the Government’s silence: disabled people are still waiting