The Britain I returned to was unrecognisable — and better for It

Dr Stephen Whitehead

- Published

- Opinion & Analysis

After a decade living in Southeast Asia, sociologist Dr Stephen Whitehead expected a divided, declining Britain. What he found instead was a confident, multicultural nation transformed by immigration — a country richer, fairer and far more interesting than the one he left behind

LISTEN: Dr Stephen Whitehead reflects on returning to Britain after ten years abroad and how the country has changed.

The last time I was in the UK, David Cameron had just won a second term as Prime Minister, Jeremy Corbyn was the new Labour party leader, the Gallagher brothers were still not on speaking terms, Brits could live, work, study and travel across EU countries without hindrance, and Prince Andrew was still the Duke of York.

But then, a decade is an age, especially in the rapidly changing 21st century. Which is why my years living in South East Asia had left me wholly unprepared for what I saw and felt once my flight landed at Heathrow two weeks ago.

Frankly, I expected the worst. At least that was the message I’d been getting from the UK media, reinforced by my British friends: “You got out at the right time”; “The UK has gone downhill”; “Everyone is either miserable or angry”; “Can I come and live with you in Thailand?”

With understandable trepidation I entered the Heathrow terminal expecting to be met by hordes of desperate immigrants trying to enter our demoralised country, shepherded by dour armed police and immigration officers equally desperate to keep them out.

None of which materialised.

Heathrow turned out to be an oasis of calm, fast, electronic efficiency, with an arrivals hall smelling only of freshly brewed coffee and not the sweaty hustlers typically found in Asian international airports. I let this pass as an aberration, and anyway, I was jet-lagged; my mind fogged by crossing seemingly endless unforgiving time-zones.

But I was noticing something strange. I was not in the majority, at least racially. That is certainly not how I left the UK, ten years ago.

My British Pakistani driver whisked me to Oxford in Mercedes comfort, chatting amiably about his ‘extremely large’ and ‘expensive to maintain’ family in London. The Portuguese hotel receptionist smiled warmly as, in perfect English, she checked me in. And the rather stressed Nigerian chambermaid rushed to finish cleaning my room. I spent three days in Oxford and only rarely got served by a white English person, even while the city itself oozes traditional white privilege and elitism amidst its self-evident globalised, eclectic student population.

The word ‘multicultural’ was by now forming in my brain, though the empirical evidence to support it was still limited.

I left Oxford by train, apprehensive as to the interminable delays which appear to bog the UK rail system, or even worse, being seated next to some crazed incel. But then I was in First Class and everyone was very polite. And very white. Multiculturalism in the UK would seem to be only lapping at the upper-class decks.

Right on time, my intercity train arrived at Knutsford, a market town in the heart of what British estate agents term the ‘Cheshire Golden Triangle’. My three days in this affluent area confirmed my growing impression of a country under dramatic change: waitresses and waiters from Brazil, Hong Kong and Ukraine; a restaurant manager from Italy; and one young lady who I mistakenly assumed to be from Spain but turned out to be born and bred in Wakefield. (OK, her family were from Madeira). During a Sunday walk around Altrincham, someone pointed out the local hotel said to be housing illegal immigrants — though by now I can no longer tell who is ‘legal’ and who isn’t.

Because the only alien around is me.

Another Mercedes car and (Indian British) driver, transported me along the M62 to Leeds, where I am due to speak at the Leeds International Festival of Ideas. By now my mind is starting to buzz with the implications of this altered UK. But I still have the rest of the north of England to explore. Has multiculturalism taken root everywhere?

While that question still hangs in the air, one question that is getting answered is about wealth. The UK is a wealthy country and don’t let anyone tell you otherwise. Every other car is a BMW, Merc, Jaguar, Range Rover, Porsche, or Tesla. I even saw a brand-new Rolls SUV. I see no rusting, fume expelling open-back pick-ups carrying buffalos, or crammed with workers, exposed to the elements, and huddled down against the rain.

The UK is tightly controlled. This is not Vietnam, Malaysia or Thailand, where the motorists compete with millions of scooters, ignore the traffic lights, speed limits, road rules and instead treat every other motorist as an impediment to their progress, to be overtaken as swiftly as possible. On the contrary, British drivers, whatever their creed, behave impeccably – for the most part. Though no doubt this is due not just to the unchanged British love for order as the ubiquitous speed cameras.

I first arrived in Leeds 50 years ago as a callow young man with a wife and one-year old child. Back then, the Yorkshire Ripper haunted the city and the only black person you’d meet would be in Chapeltown. Today, the Victorian town hall is no longer the city’s grandest building – which is probably why the council are busy updating it. Nowadays Leeds is overloaded with grand buildings. It may not feel a rich city to the average Yorkshire person, but compared to where I’ve been living it certainly is.

And Leeds is where I get my final empirical proof for what has gradually been dawning on me since arriving in the UK: During my ten-year absence, the country has become multicultural.

White British people are not the majority any more. Instead, I am surrounded by different languages, faces, skin colours, nationalities and religions. I use Leeds as my ‘test tube’. After all, I am a sociologist. I talk to the Chinese woman from Shanghai who serves me in the city’s North Face shop, the Black American bartender from Boston who serves me in at the Dakota hotel restaurant, and the Leeds Black British Uber driver still working at midnight in the city. I discuss this phenomenon with the organisers and my fellow-panel members at the Leeds International Festival of Ideas, the new CEO of Leeds City Colleges, and with my family.

And the result of this ‘research’ is unanimous. Britain is now a multicultural society. And moreover, a symbol of multiculturalism which every country would do well to follow. If the UK government is looking for a symbol of its soft power in the 21st century, just look at the wonderfully diverse population.

To be sure, not everyone is happy about that (well, not every white person) but certainly everyone I spoke to recognises this is not going to change. The UK is altered forever and no one, no politician, can change that fact.

Which I warmly applaud. I love it.

To see the UK transformed into this melting pot of cultures and identities is just fantastic. How much richer (in every way) Leeds is in 2025 compared to what it was like in 1975. And not just Leeds, Manchester and Oxford, but the whole country.

My final few days take me to my home town of Southport (no rioters today, thankfully, or murderous young males), the Lake District (a walk around Grasmere confirmed this activity to be predominantly a white one), and to the quaint, and continuingly prosperous Yorkshire market town of Northallerton (decidedly unchanged).

The driver and car taking me back to Manchester airport is a heavily bearded Muslim man from Bradford, driving a sparkling BMW estate and, in his broad Yorkshire accent, bemoaning the state of the roads, the cost of living, and the fact that no government appears capable of keeping out “all the damned immigrants”.

Are there any downsides to this apparent ‘success story’ of the UK? Sure, people have definitely put on weight over the past ten years. Which surprised me given the constant media messaging about healthy living, regular exercise and slimness equals beauty. And I had to feel sorry for the homeless people I saw in Oxford, Manchester and Leeds. Yes, there were any number of homeless people ten years ago, but nowadays who can drop a coin in their tin? Not me. Throughout my two weeks in the UK I handled no cash whatsoever. Not a penny, not a pound. I spent only by card. Just like most every other person in the country it would now seem. And the sight of Union flags fluttering from lampposts up and down the country? That just looks bizarre. Unsurprisingly, not everyone is embracing multiculturalism.

So the silver lining certainly has some clouds around it, and to be sure my visit was only fleeting, but there is no question the UK has changed and it isn’t going back to what it was. I will, however, be returning next year for another visit. I feel comfortable with the new multicultural UK.

Dr Stephen Whitehead is a sociologist, author and consultant internationally recognised for his work on gender, leadership and organisational culture. With more than two decades in academia, he served as Senior Lecturer in Education and Programme Director at Keele University before moving to Asia, where he has lived since 2009, building an international consultancy for schools and universities across the region. He is the author of 20 books, translated into 17 languages, including Men and Masculinities, Toxic Masculinity: Curing the Virus, Self-Love for Women and The End of Sex: The Gender Revolution and its Consequences. His concept of “Total Inclusivity” has been widely applied in workplaces, schools and universities, and his writing has helped shape global debate on identity, gender and organisational change. For more on Dr Stephen Whitehead’s take on modern organisations and their culture, see his recent book, Total Inclusivity at Work (London: Routledge).

READ MORE: ‘The end of corporate devotion? What businesses can learn from Gen Z‘. What does it mean when a generation resists “loving” the companies they work for? Dr Stephen Whitehead, our Leadership & Organisational Culture correspondent, explores why Gen Z’s scepticism is a survival strategy, and how organisations that recognise this can foster trust, resilience and sustainable engagement.

Do you have news to share or expertise to contribute? The European welcomes insights from business leaders and sector specialists. Get in touch with our editorial team to find out more.

Main Image Credit: TDA

Sign up to The European Newsletter

RECENT ARTICLES

-

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy -

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it -

What if he falls?

What if he falls? -

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world -

Will Trump’s Davos speech still destroy NATO?

Will Trump’s Davos speech still destroy NATO? -

Philosophers cautioned against formalising human intuition. AI is trying to do exactly that

Philosophers cautioned against formalising human intuition. AI is trying to do exactly that -

Life’s lottery and the economics of poverty

Life’s lottery and the economics of poverty -

On a wing and a prayer: the reality of medical repatriation

On a wing and a prayer: the reality of medical repatriation -

Ai&E: the chatbot ‘GP’ has arrived — and it operates outside the law

Ai&E: the chatbot ‘GP’ has arrived — and it operates outside the law -

Keir Starmer, Wes Streeting and the Government’s silence: disabled people are still waiting

Keir Starmer, Wes Streeting and the Government’s silence: disabled people are still waiting -

The fight for Greenland begins…again

The fight for Greenland begins…again -

Failure is how serious careers in 2026 will be shaped

Failure is how serious careers in 2026 will be shaped -

Poland’s ambitious plans to power its economic transformation

Poland’s ambitious plans to power its economic transformation -

Europe’s space ambitions are stuck in political orbit

Europe’s space ambitions are stuck in political orbit -

New Year, same question: will I be able to leave the house today?

New Year, same question: will I be able to leave the house today? -

A New Year wake-up call on water safety

A New Year wake-up call on water safety -

The digital euro is coming — and Europe should be afraid of what comes with it

The digital euro is coming — and Europe should be afraid of what comes with it -

Make boards legally liable for cyber attacks, security chief warns

Make boards legally liable for cyber attacks, security chief warns -

Why Greece’s recovery depends on deeper EU economic integration

Why Greece’s recovery depends on deeper EU economic integration -

Why social media bans won’t save our kids

Why social media bans won’t save our kids -

This one digital glitch is pushing disabled people to breaking point

This one digital glitch is pushing disabled people to breaking point -

Japan’s heavy metal-loving Prime Minister is redefining what power looks like

Japan’s heavy metal-loving Prime Minister is redefining what power looks like -

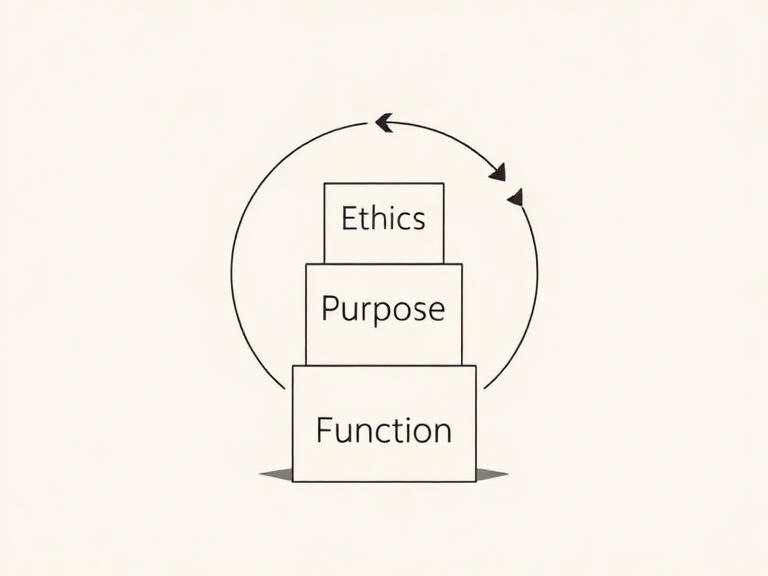

Why every system fails without a moral baseline

Why every system fails without a moral baseline -

The many lives of Professor Michael Atar

The many lives of Professor Michael Atar -

Britain is finally having its nuclear moment - and it’s about time

Britain is finally having its nuclear moment - and it’s about time