The end of corporate devotion? What businesses can learn from Gen Z

Dr Stephen Whitehead

- Published

- Opinion & Analysis

What does it mean when a generation resists “loving” the companies they work for? Dr Stephen Whitehead, our Leadership & Organisational Culture correspondent, explores why Gen Z’s scepticism is a survival strategy, and how organisations that recognise this can foster trust, resilience and sustainable engagement

LISTEN: Dr Stephen Whitehead on why Gen Z refuse corporate loyalty — and what businesses can learn from their scepticism.

Is Gen Z the most cynical generation ever? It certainly looks that way, given the proliferation of research now revealing just how untrusting, wary and sceptical this generation is, particularly towards work organisations and political institutions. We could put this down to Covid pandemic disruptions, the emotional maelstrom of social media, coupled with the general end of days mood which currently prevails across global society – so all rather depressing and pessimistic. But I prefer to see this as survivalism mixed with hard-edged realism.

To illustrate, Gen Z may well be lacking the work ethic and organisational commitment of my generation but this disconnect at least protects them from all the ‘family identity and corporate belonging’ propaganda that many major corporations aim to promote to their employees and clients. To put it another way, which generation is more attuned to the realities of life; the generation which spawned ‘salaryman’ and ‘corporate man’, or the generation which now takes to ‘lying flat’, ‘quiet quitting’ and passive resistance to the intense work culture known as “996”?

With AI about to cut a brutal and unsentimental swathe through most every type of job and employment, to me quiet quitting seems eminently sensible.

The problem is, of course, that we all want to belong to something. We may be increasingly living solo, silo lives but that doesn’t mean we want to be lonely, rejected, marooned in our apartment accompanied only by our laptop. This desire to belong, something innate in each human, is both a blessing and a curse; especially if we invest that need in flags, political parties, sports teams – or our job. In the past, it was at least feasible for a worker to feel he or she (usually a he) could have a job for life, and acquire perhaps a love for both his job and the organisation which largely enabled his comfortable life. Those days have long gone. And I say good riddance.

It is one thing to love one’s work – that makes total sense. But it is entirely another to love the organisation you work for. Why? Because such love is dangerous.

There is a fundamental flaw in humans and it is not greed, lust or selfishness. It is the need to be loved. Whether you are a new born baby or a wrinkled centenarian, nothing is more likely to bring you comfort and joy than someone giving you love and affection. But why is this most basic of needs, a flaw? Because it puts you at the mercy of your emotions and more riskily, at the mercy of the person expressing the love.

If you’ve ever been in love then you know the feeling of stepping out over a chasm, with the only thing stopping you plunging to the depths being the continued expression of love by your beloved. That’s a lot of trust, a massive amount of faith, and a galaxy of hope. No wonder it all too often ends up with us crashing down into misery. But at least when we put our trust and emotional well-being in the hands of another human being then we have the chance to measure, assess, and evaluate the risks. None of that applies if we put our trust and emotional well-being in the hands of an organisation.

One of the most common mistakes we all make when imagining, thinking about, or working in organisations is to render them real. Organisations have no ontological identity. They are not existentially functioning beings with all the characteristics of humans. Organisations may have a website, an HQ, thousands of employees, a world-wide brand image and huge profits, but they do not have a mind and nor do they have emotions. Indeed, organisations don’t even have a centre. The centre of an organisation only exists in the mind of the individual stakeholder of that organisation. The CEO and the cleaner both work in the same organisation, but those two individuals relate to it through their own experience and subjectivity; one in the executive suites, the other in the loos. Which of those subjective relationships to the organisation is the real one? Both are.

The take-away here is that organisations cannot love you. Even though you can love them. How one-sided a love affair is that?

It seems that Gen Z have at least cottoned on to the dangers inherent in loving the organisation which employs them. As I say, survivalism mixed with realism. By contrast, most of us older folks have had to learn this lesson the hard way, for example Sarah, Deputy Head of an international school in Hong Kong.

I first met Sarah when I was delivering leadership coaching to her school some years ago. The Head of the school was particularly concerned at the deteriorating relationship between her and Sarah. Nothing she tried seemed to bridge the growing gap between them. Both were highly professional, capable and experienced individuals, though the Head was much younger. After talking to Sarah it became clear she was deeply upset at not being promoted – she felt her 25 years working in the school and especially her devotion to the organisation, were not just unrewarded but largely unrecognised.

I came to realise that Sarah was not just in love with her job, she was in love with the school, the whole organisation. It had become her life to the point at which she was emotionally vulnerable to any act by the school/organisation which could be interpreted by her as ‘a lack of love’. Her work, and the organisation itself, had over many years acquired a dominant place in her life, in her sense of self, in her understanding of herself as a woman, a professional, a person respected, valued and appreciated for her devotion not to just teaching but to the organisation itself.

That is a lot of emotional investment in an entity with no heart, no mind, and no feelings.

When I explained to Sarah the difference between loving her job and loving the organisation, making the point to her that the organisation could never love her back no matter how hard she desired that love, it changed her whole relationship to her job. Well, at least to the extent that she very quickly became a lot happier. The barrier between her and the Head disappeared, her health and mental well-being appeared to improve, and she was a lot more involved, motivated and productive.

All love requires an act of magic, whereby you conjure up in your mind and imagination that which you love. We don’t only do this with other humans, we do it with animals, places, objects and with our work. Just as humans can deposit a whole mass of unrealistic and unachievable expectations onto other humans (especially romantic partners) so can employees do the same with their employing organisation. This is not a new phenomenon, but it is exacerbated by the changing nature of relationships. With so many of us now living single lives, part of an extended family network, and largely communicating with friends and loved ones via social media, where do you think we are most likely to look for that elusive love contract?

Yes, in our job. In our work. In that unfeeling, heartless organisation.

Fortunately for Gen Z they appear to be the first generation to be immune from a love contract with their employing organisation. This is really healthy for them and I hope they continue with this approach. It will save them a lot of grief, disappointment and pain.

Work organisations have the capacity to validate our sense of identity, reward us for our love and devotion to them, and give us a feeling of belonging which is surpassed only by family and partners.

What organisations don’t have the capacity to do, is love us.

Dr Stephen Whitehead is a sociologist, author and consultant internationally recognised for his work on gender, leadership and organisational culture. With more than two decades in academia, he served as Senior Lecturer in Education and Programme Director at Keele University before moving to Asia, where he has lived since 2009, building an international consultancy for schools and universities across the region. He is the author of 20 books, translated into 17 languages, including Men and Masculinities, Toxic Masculinity: Curing the Virus, Self-Love for Women and The End of Sex: The Gender Revolution and its Consequences. His concept of “Total Inclusivity” has been widely applied in workplaces, schools and universities, and his writing has helped shape global debate on identity, gender and organisational change.

Do you have news to share or expertise to contribute? The European welcomes insights from business leaders and sector specialists. Get in touch with our editorial team to find out more.

Main image: Cottonbro Studio/Pexels

RECENT ARTICLES

-

The era of easy markets is ending — here are the risks investors can no longer ignore

The era of easy markets is ending — here are the risks investors can no longer ignore -

Is testosterone the new performance hack for executives?

Is testosterone the new performance hack for executives? -

Can we regulate reality? AI, sovereignty and the battle over what counts as real

Can we regulate reality? AI, sovereignty and the battle over what counts as real -

NATO gears up for conflict as transatlantic strains grow

NATO gears up for conflict as transatlantic strains grow -

Facial recognition is leaving the US border — and we should be concerned

Facial recognition is leaving the US border — and we should be concerned -

Wheelchair design is stuck in the past — and disabled people are paying the price

Wheelchair design is stuck in the past — and disabled people are paying the price -

Why Europe still needs America

Why Europe still needs America -

Why Europe’s finance apps must start borrowing from each other’s playbooks

Why Europe’s finance apps must start borrowing from each other’s playbooks -

Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes

Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes -

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others -

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again -

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart?

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart? -

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing -

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage -

The limits of good intentions in public policy

The limits of good intentions in public policy -

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament?

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament? -

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth -

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours -

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality -

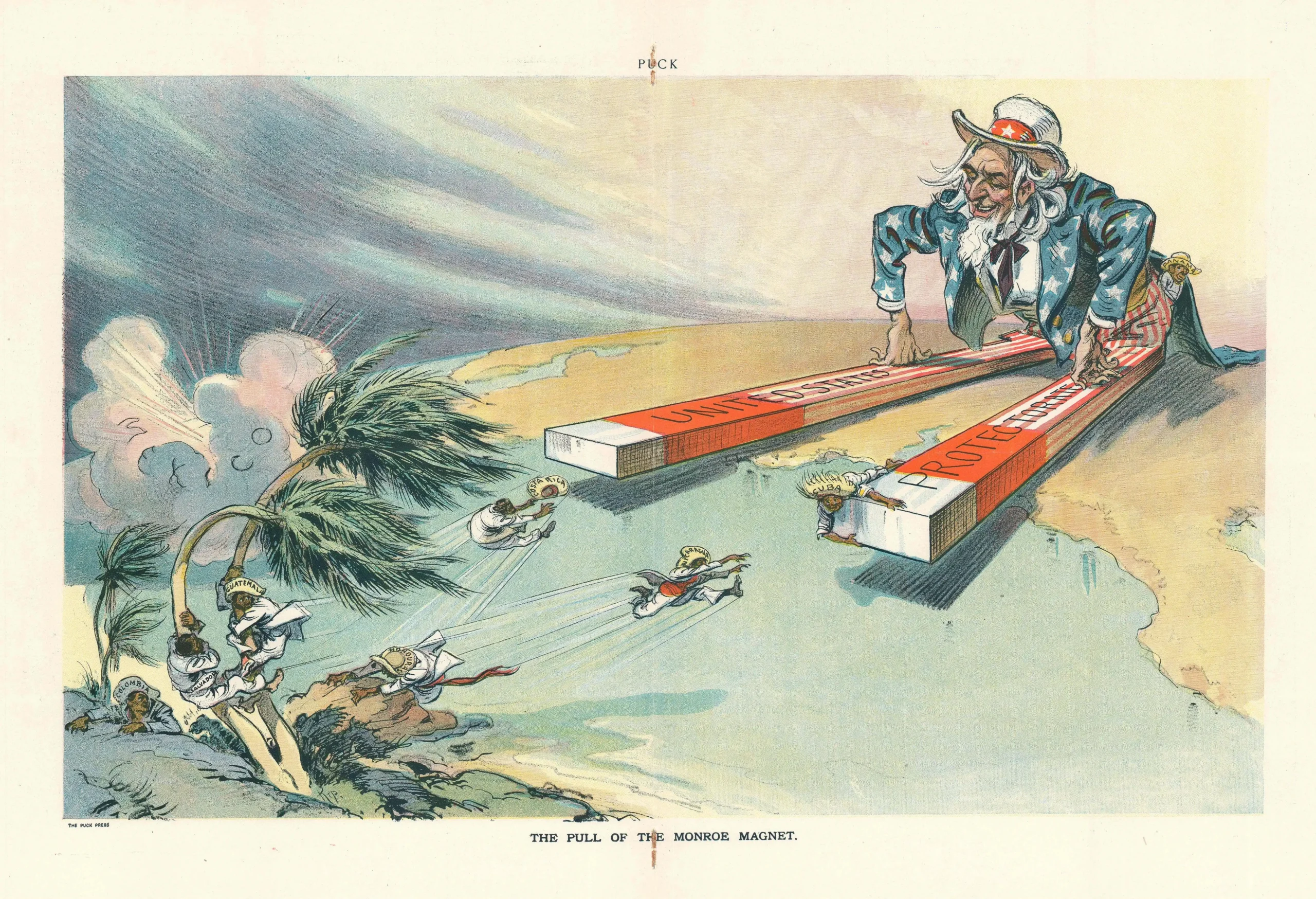

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now -

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day -

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy -

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it -

What if he falls?

What if he falls? -

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world