Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes

Vendan Ananda Kumararajah

- Published

- Opinion & Analysis

While AI tools are now embedded in everyday university life across Europe, the absence of clear institutional rules, shared standards and enforceable governance is creating ambiguity, inequity and a gradual erosion of trust at the heart of academic systems, writes Vendan Ananda Kumararajah

Universities across Europe are already operating in an AI-enabled reality. Students use large language models to draft essays, summarise readings, generate code, and structure arguments. Academics, meanwhile, use AI to accelerate research, review literature, and prepare teaching materials. Yet despite this widespread adoption, academia still lacks something fundamental: clear rules of engagement. In the absence of that clarity, ambiguity takes hold and steadily erodes trust in academic systems.

The current state of play is paradoxical. AI tools are everywhere in higher education, yet governance is nowhere. Institutions oscillate between informal tolerance, outright bans, or vague guidance that shifts responsibility onto individual lecturers and students.

This leaves everyone uncertain. What counts as acceptable assistance? Where does learning end and automation begin? Who is accountable when AI-generated work enters assessment systems? Without clear boundaries, neither students nor educators are operating on a level playing field.

Academic integrity has always rested on transparency, attribution, and demonstrable understanding. AI, however, disrupts all three.

When students submit work partially or wholly shaped by automated systems, the ethical question is not merely whether AI was used, but how, where, and with what justification. In the absence of formal AI infrastructure and governance rules, ethical judgement becomes subjective, inconsistent, and vulnerable to dispute.

This is unfair to students, who are left guessing what is permissible, and to educators, who are asked to police behaviour without institutional backing. Ethics cannot be enforced through ambiguity. They must be designed into the system.

One of the least discussed consequences of unmanaged AI use in academia is inequity. Some students have access to premium tools, stronger prompts or informal guidance, while others rely on free versions or avoid AI altogether through uncertainty. Departments vary in their tolerance, with some encouraging experimentation and others treating it as misconduct. This landscape creates structural unfairness and weakens the basis of academic meritocracy.

When institutions fail to define shared rules of engagement, advantage accrues unevenly and the principle of fair assessment is steadily undermined.

Perhaps the most serious concern of all is pedagogical.

AI can accelerate learning but it can also bypass it. When automated prompts generate polished answers, students may produce convincing work without acquiring underlying domain knowledge. Critical thinking, synthesis, and argumentation risk being replaced by surface coherence.

The question universities must confront is not whether AI is “good” or “bad”, but whether current usage supports or undermines learning objectives. If students cannot defend, critique, or explain AI-assisted outputs, the educational contract has already been broken.

Universities are trusted institutions because they produce knowledge that is aligned with disciplinary standards, critically reasoned, and defensible under scrutiny. Unregulated AI use weakens that trust, and when neither students nor institutions can clearly account for how knowledge is produced, confidence in academic outputs erodes internally and in the eyes of employers, regulators, and society. This is happening already.

The solution, in my view, is not prohibition. Blanket bans are unenforceable and intellectually dishonest. Nor is laissez-faire adoption viable. What is needed is institutional AI governance that is practical, transparent, and enforceable.

Two steps are essential.

First, internal, institute- or course-specific AI platforms. Rather than relying on uncontrolled external tools, institutions should provide curated AI environments aligned with course objectives, assessment methods, and ethical standards. This creates traceability, consistency, and shared expectations.

Second, clear rules of engagement. Students should know when AI may be used, for what purposes, with what disclosure, and how they are expected to defend and critically analyse AI-assisted work. AI should be treated as an intellectual instrument, not a shortcut and its use should always remain visible, discussable, and examinable.

European academia has navigated previous technological shifts such as calculators, the internet, digital libraries by updating norms and governance, not by pretending change could be stopped. AI is no different, except in scale.

The choice now is stark: either institutions design AI governance intentionally, or they allow trust, integrity, and learning outcomes to erode by default.

In academia, as in society, trust depends on structure rather than silence.

Vendan Ananda Kumararajah is an internationally recognised transformation architect and systems thinker. The originator of the A3 Model—a new-order cybernetic framework uniting ethics, distortion awareness, and agency in AI and governance—he bridges ancient Tamil philosophy with contemporary systems science. A Member of the Chartered Management Institute and author of Navigating Complexity and System Challenges: Foundations for the A3 Model (2025), Vendan is redefining how intelligence, governance, and ethics interconnect in an age of autonomous technologies.

READ MORE: ‘Why social media bans won’t save our kids‘. Politicians are rushing to block under-16s from social platforms, but the danger runs much deeper than screen time or teenage scrolling, warns Vendan Ananda Kumararajah. The real threat lies in systems built for profit, not childhood, and only a redesign of the platforms themselves will make the online world genuinely safe for young people.

Do you have news to share or expertise to contribute? The European welcomes insights from business leaders and sector specialists. Get in touch with our editorial team to find out more.

Main image: Pixabay

RECENT ARTICLES

-

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others -

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again -

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart?

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart? -

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing -

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage -

The limits of good intentions in public policy

The limits of good intentions in public policy -

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament?

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament? -

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth -

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours -

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality -

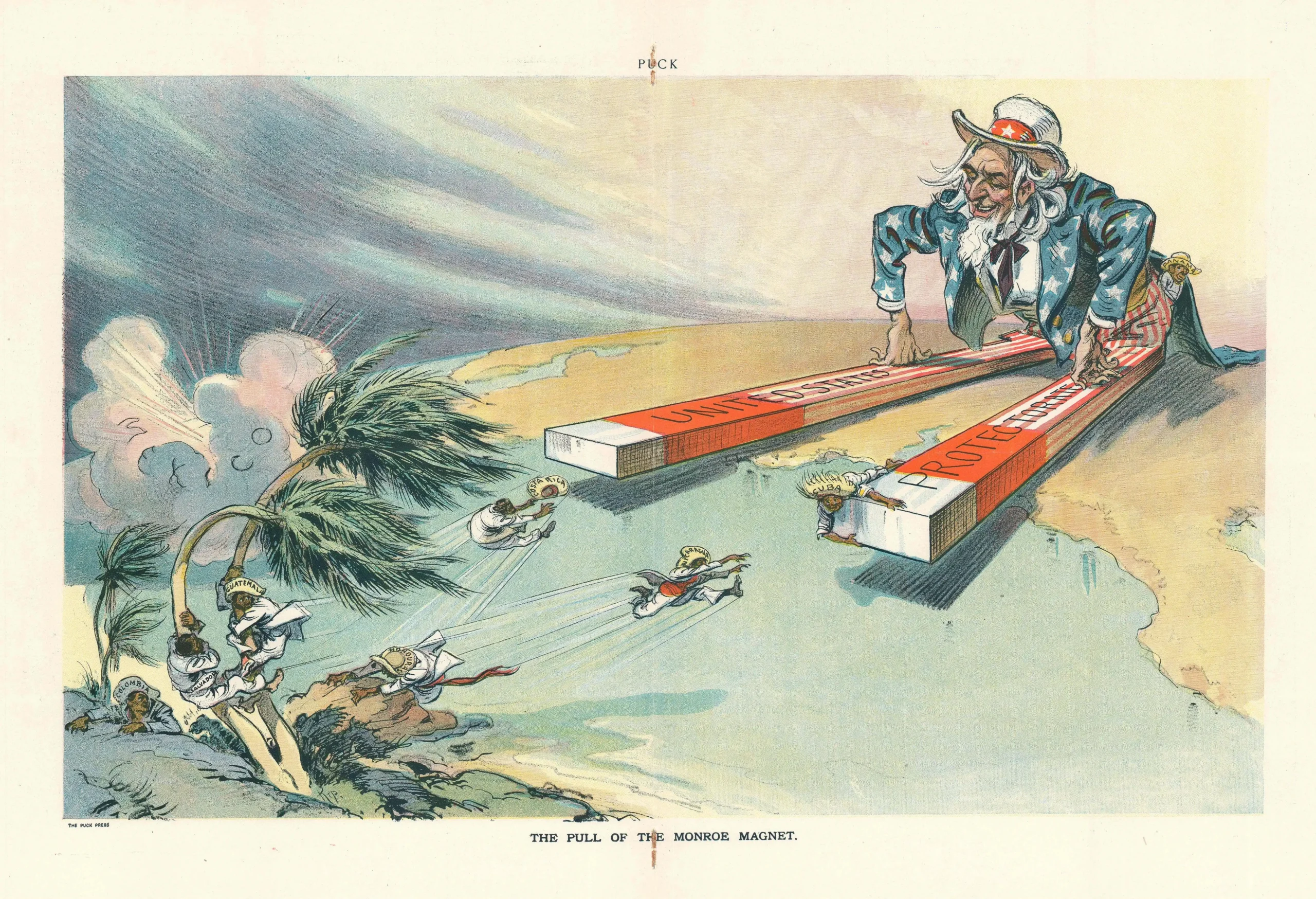

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now -

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day -

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy -

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it -

What if he falls?

What if he falls? -

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world -

Will Trump’s Davos speech still destroy NATO?

Will Trump’s Davos speech still destroy NATO? -

Philosophers cautioned against formalising human intuition. AI is trying to do exactly that

Philosophers cautioned against formalising human intuition. AI is trying to do exactly that -

Life’s lottery and the economics of poverty

Life’s lottery and the economics of poverty -

On a wing and a prayer: the reality of medical repatriation

On a wing and a prayer: the reality of medical repatriation -

Ai&E: the chatbot ‘GP’ has arrived — and it operates outside the law

Ai&E: the chatbot ‘GP’ has arrived — and it operates outside the law -

Keir Starmer, Wes Streeting and the Government’s silence: disabled people are still waiting

Keir Starmer, Wes Streeting and the Government’s silence: disabled people are still waiting -

The fight for Greenland begins…again

The fight for Greenland begins…again -

Failure is how serious careers in 2026 will be shaped

Failure is how serious careers in 2026 will be shaped -

Poland’s ambitious plans to power its economic transformation

Poland’s ambitious plans to power its economic transformation