What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now

Mike Bedenbaugh

- Published

- Opinion & Analysis

When President Donald Trump justified action in Venezuela by invoking a new “Donroe Doctrine”, he attached a modern intervention to the name of a little-understood 1823 American policy that originally promised the opposite: that Europe would stay out of the Americas and America would stay out of Europe. Political analyst Mike Bedenbaugh explains how that promise changed over two centuries into something very different, and why hearing it revived now tells Europeans far more about today’s United States than about its founders

Europeans watching the United States today are right to be confused.

When American political figures invoke the so-called ‘Monroe Doctrine’ to justify a more aggressive, unilateral posture in the Western Hemisphere, it sounds to us historians less like a lesson from history and more like a slogan pulled from a marketing deck. To understand why this matters — and why recent references to a so-called “Donroe Doctrine” misrepresent both American history and international law — one must return to what the Monroe Doctrine actually was, who authored it, and what it was never intended to become.

The Monroe Doctrine emerged in 1823 at a very specific moment in world history. The Napoleonic Wars had ended, Europe’s great powers were attempting to restore old monarchies, and across Latin America former Spanish colonies were fighting — and winning — wars of independence. The question facing the young United States was not how to dominate its hemisphere, but how to survive in it.

Contrary to popular belief, the doctrine was not a declaration of American power.

President James Monroe, the last president of the Revolutionary generation, delivered the doctrine in his annual message to Congress. But its intellectual author was his Secretary of State, John Quincy Adams — a man steeped in diplomatic realism and deeply wary of empire. Adams understood that the United States, barely fifty years old, lacked the military capacity to enforce grand ambitions abroad. What it did possess was moral clarity born from its own anti-colonial revolution.

The core principle of the Monroe Doctrine was simple: the Western Hemisphere was no longer open to European colonisation, and European powers should not attempt to reassert control over nations that had chosen independence. In return, the United States pledged non-interference in European affairs. It was a mutual restraint doctrine, not a licence for intervention.

Adams was explicit about this. The doctrine was designed to support the sovereignty of nations choosing self-government — not to impose American preferences upon them. It rested on a kind of revolutionary brotherhood: former colonies recognising one another’s right to chart their own political destinies without external domination.

This is where modern reinterpretations go wrong.

Current administration figures such as Stephen Miller have publicly invoked the Monroe Doctrine as justification for a more assertive U.S. posture in the hemisphere, conflating it with later corollaries and Cold War practices. This is historically inaccurate. The original doctrine said nothing about regime change, military intervention, or economic coercion. In fact, Adams famously warned that if America went abroad “in search of monsters to destroy,” it would lose its soul and become an empire rather than a republic.

The doctrine changed — but only later, and not benignly.

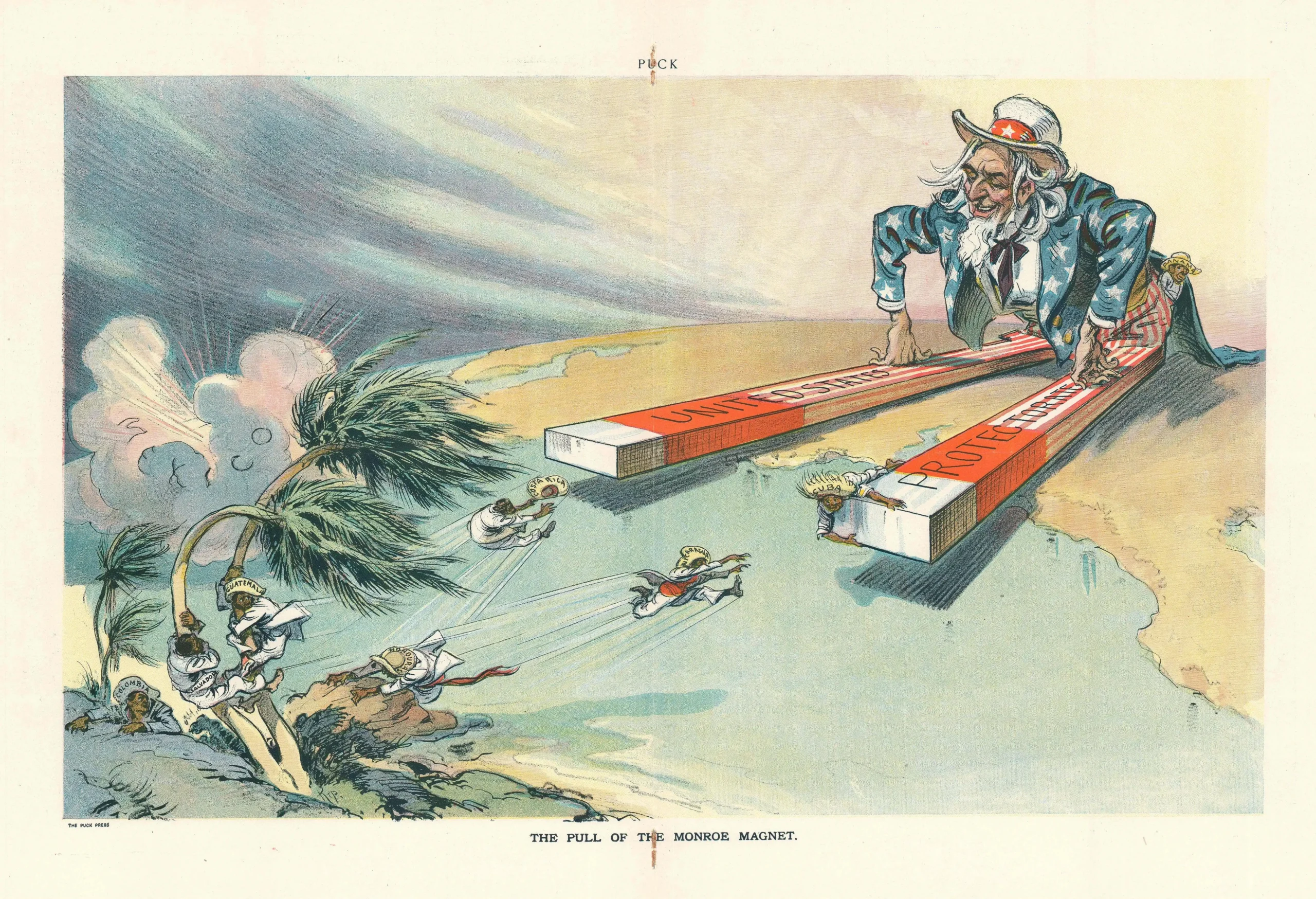

At the turn of the twentieth century, Theodore Roosevelt introduced what became known as the Roosevelt Corollary. Under this reinterpretation, the United States claimed the right to intervene in Latin American nations to pre-empt European involvement, particularly over debt disputes. This marked a sharp departure from Monroe and Adams’ original vision. Sovereignty became conditional. Stability, as defined by Washington, replaced self-determination.

The transformation accelerated during the Cold War. The Dulles brothers — John Foster Dulles as Secretary of State and Allen Dulles as Director of the CIA — advanced an interventionist doctrine that bore little resemblance to Monroe’s. Governments across Latin America were destabilised or overthrown not because they invited outright European colonisation, but because they failed to align with American strategic or corporate interests due to socialist economic systems. Democratic legitimacy mattered less than ideological obedience and economic dominance.

These actions were justified retroactively under the banner of the Monroe Doctrine, but they were, in truth, repudiations of it.

Understanding Monroe’s place in American history matters for another reason as well. He was the last president who belonged fully to the founding generation — men shaped directly by revolution, restraint, and fear of concentrated power. While John Quincy Adams would later become president, he was the son of the founder John Adams. The psychological shift matters.

What followed Monroe and JQ Adams was a transformation in American political culture embodied most clearly by Andrew Jackson. Jackson was a war hero, a populist, and a deeply polarising figure. His presidency marked the rise of mass party politics, executive assertiveness, and a militarised approach to governance. So alarmed were his contemporaries by his authoritarian tendencies that an entire political party — the Whigs — formed primarily to oppose him and his policies.

This is the lineage that our current strongman president most closely resembles.

And yet, the administration and its political allies often present themselves as heirs to the Founders, invoking figures like Monroe to frame contemporary power politics in revolutionary legitimacy. This reflects political branding more than historical continuity. The Founders feared concentrated authority. Jackson’s presidency expanded it. Monroe avoided interventionism. Post-war leaders made intervention more common.

For European audiences, the distinction is not academic. When American policymakers cite the Monroe Doctrine to rationalise unilateral action, they are not channelling the caution of the early republic — they are selectively appropriating its language while rejecting its substance.

This misappropriation becomes clearer when one looks not only at doctrine, but at symbolism. President Trump has been unusually explicit about which historical figure he sees as his true predecessor. He has repeatedly insisted on placing a portrait of Andrew Jackson behind the Resolute Desk, positioning Jackson — not Monroe, not Adams — as his chosen point of inspiration.

That choice matters.

Andrew Jackson did not inherit the restraint of the founding generation; he broke from it. His presidency marked the decisive turn towards executive dominance, militarised nationalism, and an openly confrontational approach to both domestic opposition and foreign policy. Jackson treated political resistance not as a feature of republican governance, but as an obstacle to be crushed. His Indian removal policies, his defiance of the Supreme Court, and his personalisation of executive authority alarmed contemporaries across the political spectrum.

So alarmed, in fact, that a new political movement emerged with the explicit purpose of stopping him.

The Whig Party, drawing inspiration from the British Whigs who opposed monarchical power and American Revolutionary patriots who fought King George III, was not born out of abstract ideology, but out of fear — fear that Jackson’s concentration of power, populist militarism, and contempt for institutional limits threatened the republic itself. Its founders saw Jackson not as a continuation of the Founders’ project, but as a warning about how republics slide towards strongman rule.

Here, history offers a question rather than a conclusion.

If President Trump is indeed inspired by Jackson rather than Monroe — if he embraces Jackson’s militancy while cloaking it in Monroe’s language — will the political consequences follow the same path? Will America once again see the formation of a broad opposition movement defined less by party loyalty than by resistance to executive overreach?

The irony is striking. The nineteenth-century Whig Party, formed to oppose Jacksonian authoritarianism, dissolved within a generation. Yet its ideas, personnel, and institutional DNA became part of the foundation of the Republican Party that Donald Trump now leads today.

Europe now confronts an American reality shaped less by the restraint of Monroe than by the assertiveness of Jackson — a republic testing how far power can be personalised before institutions and citizens respond. The language of the Founders is being reused, but the governing instinct is unmistakably post-founding, rooted in force, spectacle, and executive will. History suggests that such moments do not end in stasis: they provoke correction.

Whether that correction comes through renewed constitutional balance or through the birth of a new political alignment, as it once did in the age of Jackson, remains an open question.

What is certain is that Europe is no longer engaging with the America of inherited assumptions, but with one still deciding what kind of government it intends to be, and what kind of force it intends to utilise to defend itself against its perceived adversaries; both foreign and domestic.

Author and political thinker Michael Bedenbaugh is a respected voice in constitutional principles and American governance. Based in South Carolina, he is deeply involved in his home state’s development while contributing to national discussions on governance and civic engagement, most recently as standing as an independent candidate for Congress. He is the author of Reviving Our Republic: 95 Theses for the Future of America and the host of YouTube channel Reviving Our Republic with Mike Bedenbaugh.

READ MORE: ‘Tariffs and the American dilemma: old tools, new tensions‘. In this timely analysis, our U.S political correspondent Michael Bedenbaugh traces the rise of tariffs from their Hamiltonian origins to their modern role as a blunt instrument of nationalist politics. Drawing on personal experience and the economic fallout in his native South Carolina, he examines how trade policy has become a source of domestic division and international concern, and why Europe should be paying close attention.

Do you have news to share or expertise to contribute? The European welcomes insights from business leaders and sector specialists. Get in touch with our editorial team to find out more.

Main image: The Pull of the Monroe Magnet highlights the interventionist and paternalistic practices of the United States in Latin America; cartoon in Puck by Udo Keppler, 1913. Credit: Udo Keppler, Puck magazine, 1913 (Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

RECENT ARTICLES

-

Why Europe still needs America

Why Europe still needs America -

Why Europe’s finance apps must start borrowing from each other’s playbooks

Why Europe’s finance apps must start borrowing from each other’s playbooks -

Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes

Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes -

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others -

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again -

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart?

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart? -

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing -

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage -

The limits of good intentions in public policy

The limits of good intentions in public policy -

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament?

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament? -

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth -

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours -

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality -

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now -

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day -

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy -

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it -

What if he falls?

What if he falls? -

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world -

Will Trump’s Davos speech still destroy NATO?

Will Trump’s Davos speech still destroy NATO? -

Philosophers cautioned against formalising human intuition. AI is trying to do exactly that

Philosophers cautioned against formalising human intuition. AI is trying to do exactly that -

Life’s lottery and the economics of poverty

Life’s lottery and the economics of poverty -

On a wing and a prayer: the reality of medical repatriation

On a wing and a prayer: the reality of medical repatriation -

Ai&E: the chatbot ‘GP’ has arrived — and it operates outside the law

Ai&E: the chatbot ‘GP’ has arrived — and it operates outside the law -

Keir Starmer, Wes Streeting and the Government’s silence: disabled people are still waiting

Keir Starmer, Wes Streeting and the Government’s silence: disabled people are still waiting