The hidden cost of wild swimming: how our cold water craze is harming the planet

Ben Hooper

- Published

- Opinion & Analysis

From neoprene wetsuits to car emissions and polluted rivers, the boom in wild swimming comes with an environmental toll. On World Environment Day, Ben Hooper reports on the carbon footprint, ecological risks and sustainability challenges of the UK’s fastest-growing fitness trend

Once dismissed as the eccentric pastime of pensioners in woolly swimsuits, wild swimming has become one of the UK’s most explosive outdoor trends. Over 11 million people took to open water in 2022 alone — a surge driven first by social media, then cemented by the COVID-19 lockdowns that shut gyms and pools across the country.

Today, what was once a niche activity is worth £2.4 billion a year to the UK economy and is credited by Sport England with saving the NHS some £357 million annually in health and social care costs. From tidal rivers and remote lakes to beach coves and repurposed quarries, Britain’s wild waters now welcome an estimated half a million swimmers every month.

But as we mark World Environment Day and the number of swimmers soars, so too do the questions. What toll is this watery revolution taking on the environment? What is the hidden cost — in carbon, chemicals and consumption — of a movement founded on personal wellbeing but sustained by wetsuits, road trips and social media?

According to HM Coastguard, callouts related to open water swimming rose by 51% between 2018 and 2021, with fatalities increasing by 79%. Despite the risks, its appeal remains powerful, whether for challenge, fitness or a moment of calm.

Jane, 43, from Cumbria, swims year-round in her local lakes. “No matter the weather, I get out on the water and let my worries float away,” she told me. “It makes me feel alive.” Pete, 32, from East London and a triathlete who I met this week, put it more bluntly: “Colder the better. I want to win. Cold water makes me push the limits.”

But those limits come not only from physical endurance or personal risk. Cold water immersion in the UK increasingly means entering rivers and lakes affected by agricultural runoff, sewage discharge and high bacteria counts. “The risk of getting sick from polluted water is real,” Professor Mike Tipton, a leading expert in environmental physiology, told me yesterday. His colleague, Professor Harper, is overseeing a randomised controlled trial to study the mental health effects of cold water swimming, but warns that many of the reported benefits remain anecdotal. “The long-term health effects aren’t yet fully understood,” Harper told me. “And while the body can adapt to cold water, a lot of the data so far is observational. We’re still catching up.”

If you’re new to open water or cold-water swimming, you may also want to read The Cold Truth: Why Wild Swimming Is Riskier Than You Think, in which Professor Tipton talks about the real dangers of cold water immersion, from cardiac risk to cold shock and muscle failure. It’s a vital read for anyone entering the water this season.

The Slippery Problem of Neoprene

One of the most significant — and least discussed — environmental issues is the wetsuit itself. Made primarily from neoprene, a petroleum-based synthetic rubber, wetsuits are resource-intensive to produce and difficult to recycle. Global neoprene production was valued at $1.37 billion in 2023 and is forecast to reach $3.4 billion by 2032. Just one kilo of neoprene releases between 182,000g and 196,000g of CO₂ during production.

With over 20 major wetsuit brands active in the UK, the numbers stack up. But so too do the efforts to reduce the impact. Brands such as HUUB have introduced recycling schemes that save an estimated 380 tonnes of neoprene waste from landfill each year. Osprey, Sumapro and Patagonia are also investing in eco-friendly alternatives — including hypoallergenic and recycled materials — though prices remain high.

The Carbon Footprint of Travel

Even before they hit the water, most swimmers have already contributed to carbon emissions. Whether it’s a 20-minute drive to a local lake or a full weekend escape in a VW camper van, open water swimming often involves travel. The average carbon footprint of a single Volkswagen van is 47.3 tonnes of CO₂ over its lifecycle, excluding the emissions from each individual trip.

With many outdoor swimmers living far from swimmable water, and the number of indoor pools in decline, this reliance on car travel is likely to grow. The irony is stark: in escaping to nature, many swimmers inadvertently add to its degradation.

Water Quality and Waste

Another pressing concern is the water itself. Poor-quality rivers, agricultural pollution, and untreated sewage regularly push UK waterways below recommended bathing standards. Wessex Water estimates it would cost more than £100 million — and generate over 1,000 tonnes of additional carbon emissions — to upgrade its infrastructure with UV purification systems to make its waters reliably safe for swimming.

The solution, say campaigners and swimmers alike, must involve government support and better regulation. Local actions, such as picking up litter and lobbying against fly-tipping, are crucial, but not enough on their own.

Some swimmers are taking the lead. I know many wild swimmers who actively challenge littering and fly-tipping. They take pride in protecting the very places they swim. But without systemic support from water companies and government, their efforts can only go so far.

Time to Tread Lighter

British Swimming has now launched an environmental sustainability strategy to help athletes and organisations measure and reduce their carbon footprint. But for the wider wild swimming community, the message is equally clear: it’s time to swim with conscience.

That means investing in sustainable gear, carpooling or using public transport where possible, challenging poor water quality, and always taking waste home. Our lakes, rivers and oceans are already under pressure from overfishing, pollution and climate change. The last thing they need is more pressure from those who claim to love them most.

As wild swimming continues to grow, its environmental footprint must not be ignored. Because in the end, saving ourselves cannot come at the expense of the waters that save us.

Ben Hooper hit the international headlines after revealing what has been described as one of the world’s most ambitious expeditions: to swim “every single mile” of the Atlantic Ocean – according to Sir Ranulph Fiennes OBE, the last great bastion to be conquered. Ben’s intended journey, across two-thousand miles of open ocean between Senegal and Brazil, would take up to 4-months, and would enter the record books. The expedition, called ‘Swim the Big Blue’, following Ben’s death from swimming into thousands of left-over Portuguese Man O’War tentacles and his incredible restart, mid-Atlantic, was eventually thwarted by adverse weather conditions damaging his support vessel. It was a devastating blow following years of painstaking dedication and training. Today, Ben holds the only WOWSA verified attempt to swim the full extent of The Atlantic Ocean.

Main photo: Diana Rafira/Pexels

RECENT ARTICLES

-

Can we regulate reality? AI, sovereignty and the battle over what counts as real

Can we regulate reality? AI, sovereignty and the battle over what counts as real -

NATO gears up for conflict as transatlantic strains grow

NATO gears up for conflict as transatlantic strains grow -

Facial recognition is leaving the US border — and we should be concerned

Facial recognition is leaving the US border — and we should be concerned -

Wheelchair design is stuck in the past — and disabled people are paying the price

Wheelchair design is stuck in the past — and disabled people are paying the price -

Why Europe still needs America

Why Europe still needs America -

Why Europe’s finance apps must start borrowing from each other’s playbooks

Why Europe’s finance apps must start borrowing from each other’s playbooks -

Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes

Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes -

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others -

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again -

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart?

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart? -

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing -

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage -

The limits of good intentions in public policy

The limits of good intentions in public policy -

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament?

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament? -

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth -

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours -

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality -

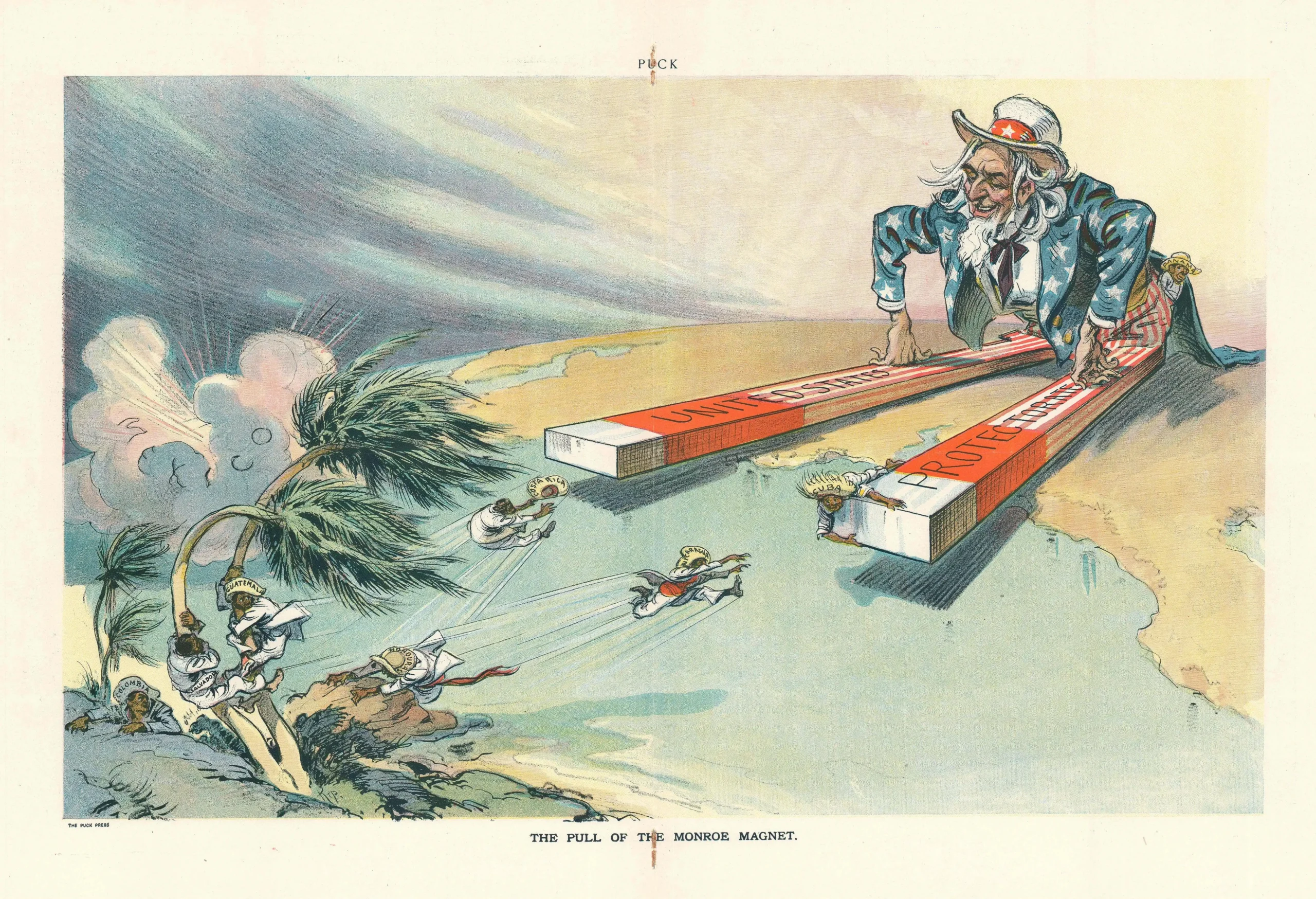

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now -

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day -

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy -

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it -

What if he falls?

What if he falls? -

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world -

Will Trump’s Davos speech still destroy NATO?

Will Trump’s Davos speech still destroy NATO? -

Philosophers cautioned against formalising human intuition. AI is trying to do exactly that

Philosophers cautioned against formalising human intuition. AI is trying to do exactly that