The Tokyo war crimes trial: an explainer 77 years on

Dr Linda Parker

- Published

- Opinion & Analysis

Dr Linda Parker explores the Tokyo War Crimes Trial, where 28 Japanese leaders faced justice in a case that still sparks debate over victors’ justice, command responsibility and the legacy of international law

This November marks 77 years since the verdicts of the Tokyo War Crimes Trial, formally known as the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (IMTFE). Convened by the Allies in the aftermath of the Second World War, the tribunal was the counterpart to Nuremberg, seeking to hold Japan’s wartime leaders accountable.

While less famous than Nuremberg, the Tokyo trial has shaped international law and continues to divide opinion. Was it a landmark in the fight against impunity, or simply “victor’s justice” imposed by the winners of the war?

This explainer looks back at what happened, who stood trial, who did not, and why the judgments remain controversial nearly eight decades later.

What was the Tokyo War Crimes Trial?

The tribunal was established in Tokyo in January 1946, just five months after Japan’s surrender, under the authority of General Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers. It opened on 29 April 1946 in Courtroom No. 27 of the former Japanese Army Ministry building at Ichigaya.

It sat for two years and seven months, examining Japanese actions from the invasion of Manchuria in 1931, through the full-scale war with China in 1937, and the wider Pacific conflict following Pearl Harbor in 1941, until Japan’s defeat in 1945. By September 1948, the judges were debating draft opinions and sentencing. The revised judgments were finalised in early October, and on 12 November 1948 they were read aloud in court, bringing the proceedings to a close.

The trial tested a new legal principle: that senior leaders — not just soldiers — could be held individually responsible for planning and waging aggressive wars, labelled “crimes against peace,” and for atrocities they knew of but failed to prevent.

Who was on trial?

In total, 28 political and military leaders faced charges on 55 counts. Only those accused of Class A crimes (planning and waging wars of aggression) alongside other crimes were tried in Tokyo; others were prosecuted in separate Allied-run courts across Japan and South East Asia.

The charges were divided into three categories:

Class A: crimes against peace (planning and starting wars of aggression).

Class B: conventional war crimes.

Class C: crimes against humanity.

Among those convicted were:

Hideki Tojo, Army Chief of Staff in 1937 and Prime Minister from 1941–44, found guilty of waging aggressive war and overseeing atrocities in China.

Kenji Doihara, a general who played a key role in the 1931 invasion of Manchuria.

The most conspicuous absence was Emperor Hirohito. Evidence suggested he had been involved in planning wars of aggression, yet MacArthur exempted him from indictment. MacArthur believed Hirohito’s symbolic role was essential to stabilising post-war Japan. Sparing the Emperor secured public cooperation with the Allied occupation and reforms, while avoiding the risk of turning him into a martyr.

What evidence was heard?

The tribunal examined thousands of documents dating back to the early 1930s. Prosecutors presented more than 4,000 pieces of evidence, including 779 affidavits and depositions, and the court heard from 419 witnesses.

Key prosecution material included the diary of Marquis Koichi Kido, close adviser to Hirohito, which detailed internal discussions on Japan’s war planning.

The defence — three-quarters Japanese lawyers, one-quarter American — mounted a spirited case. They argued, for example, that Japan’s expansion into China was a stabilising intervention rather than aggression. Reports by the American journalist Willis Abbotts supported this interpretation, but were excluded for lack of corroborating documents. Critics said the tribunal relied too heavily on paperwork and written statements, sidelining valuable testimony.

Who were the judges?

The panel comprised 11 judges from the Allied nations. Sir William Flood Webb of Australia served as Chief Judge. Others represented China, India, the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, New Zealand, the Netherlands, the Soviet Union, France and the Philippines.

Each nation brought its own agenda. The Soviet Union pressed for the harshest sentences. China, which considered itself the most damaged by Japan, also urged recognition of the suffering of other Asian nations.

Despite months of debate, most judges eventually supported the majority verdicts. The most famous dissent came from Radhabinod Pal of India, who argued that aggressive war and conspiracy to wage it were not illegal under international law at the time, and therefore all defendants should be acquitted. Judges from France and the Netherlands also dissented in part, but the final judgments were carried by majority.

What sentences were handed down?

The tribunal sentenced seven defendants to death; they were executed in December 1948. A further 16 received life imprisonment, but most were paroled between 1954 and 1956.

This reflected both Japanese civil law, which allowed parole, and growing domestic pressure for leniency. It also mirrored a shift in US policy: as the Cold War deepened, Washington sought a close anti-communist partnership with Japan, softening its stance towards former leaders.

Why has the judgment been controversial?

The Tokyo trial has been contested from the start. Critics point to:

Limits on defence evidence: much was excluded on grounds of hearsay, provenance or lack of documentation, even when it challenged the central charge of crimes against peace.

Selective justice: Allied actions, such as the firebombing of Japanese cities and the use of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, were never considered.

The Emperor’s exemption: sparing Hirohito, widely regarded as the head of state, undermined the tribunal’s credibility.

Indian judge Pal dismissed the trial as “victor’s justice,” carried out in a spirit of retribution. Modern legal scholars, such as Guénaël Mettraux, note that the Tokyo tribunal left unresolved tensions about command responsibility — questions that continue to complicate international law.

Yet the trial also influenced the future of war crimes justice. It established that leaders can be held accountable for crimes committed under their authority, and clarified the definition of crimes against humanity. Its refusal to admit hearsay or undocumented evidence helped shape the rules of evidence in later tribunals. The Tokyo trial informed the international courts for Yugoslavia and Rwanda, and ultimately underpinned the creation of the International Criminal Court.

How is it viewed in Japan today?

During the Allied occupation and immediate post-war years, the Japanese public largely accepted the verdicts. Over time, interest faded as a new generation grew up. Today, polls show that many Japanese citizens are unaware of the details of the trial.

Academic interest, however, has grown, particularly around anniversaries. In 2005, for example, the University of Tokyo’s Graduate School organised a major symposium on the tribunal’s legacy in Asia. Scholars continue to debate whether the trial was an imposition on Japan’s sovereignty or a vital step towards international legal cooperation. Nationalist and conservative groups often resent its long-term implications, while academics tend to stress its importance for legal progress.

A legacy still unsettled

Seventy-seven years later, the Tokyo War Crimes Trial remains both milestone and controversy. It brought Japan’s wartime leaders before a court of law, but left unresolved questions about the Emperor’s responsibility, the legality of aggressive war, and the accountability of the Allies themselves.

Its influence on later war crimes tribunals and the development of the International Criminal Court is clear — but so too is the debate it continues to provoke.

READ MORE: This article forms part of Dr Linda Parker’s ongoing series for The European on military history and its contemporary lessons. You can read previous articles by Dr Linda Parker here.

Dr. Linda Parker is widely considered to be one of Britain’s leading polar and military historians. She is the author of six acclaimed books, an in-demand public speaker, the co-founder of the British Modern Military History Society, and the editor of Front Line Naval Chaplains’ magazine, Pennant, which examines naval chaplaincy’s historical and contemporary role.

Main image: The International Criminal Court in The Hague, Netherlands. The Tokyo war crimes trial helped lay the foundations for modern international justice. Credit: Photo by Jan van der Wolf / Pexels

Sign up to The European Newsletter

RECENT ARTICLES

-

The digital euro is coming — and Europe should be afraid of what comes with it

The digital euro is coming — and Europe should be afraid of what comes with it -

Why Greece’s recovery depends on deeper EU economic integration

Why Greece’s recovery depends on deeper EU economic integration -

Why social media bans won’t save our kids

Why social media bans won’t save our kids -

This one digital glitch is pushing disabled people to breaking point

This one digital glitch is pushing disabled people to breaking point -

Japan’s heavy metal-loving Prime Minister is redefining what power looks like

Japan’s heavy metal-loving Prime Minister is redefining what power looks like -

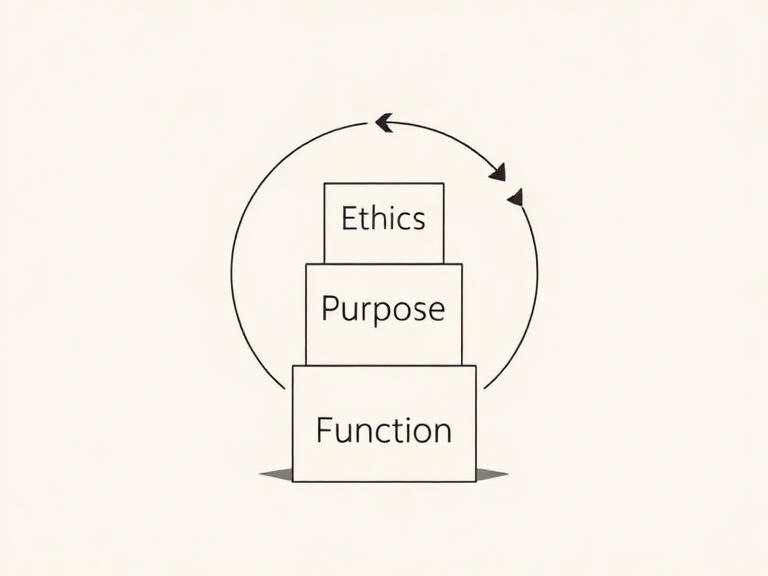

Why every system fails without a moral baseline

Why every system fails without a moral baseline -

The many lives of Professor Michael Atar

The many lives of Professor Michael Atar -

Britain is finally having its nuclear moment - and it’s about time

Britain is finally having its nuclear moment - and it’s about time -

Forget ‘quality time’ — this is what children will actually remember

Forget ‘quality time’ — this is what children will actually remember -

Shelf-made men: why publishing still favours the well-connected

Shelf-made men: why publishing still favours the well-connected -

European investors with $4tn AUM set their sights on disrupting America’s tech dominance

European investors with $4tn AUM set their sights on disrupting America’s tech dominance -

Rachel Reeves’ budget was sold as 'fair' — but disabled people will pay the price

Rachel Reeves’ budget was sold as 'fair' — but disabled people will pay the price -

Billionaires are seizing control of human lifespan...and no one is regulating them

Billionaires are seizing control of human lifespan...and no one is regulating them -

Africa’s overlooked advantage — and the funding gap that’s holding it back

Africa’s overlooked advantage — and the funding gap that’s holding it back -

Will the EU’s new policy slow down the flow of cheap Chinese parcels?

Will the EU’s new policy slow down the flow of cheap Chinese parcels? -

Why trust in everyday organisations is collapsing — and what can fix it

Why trust in everyday organisations is collapsing — and what can fix it -

In defence of a consumer-led economy

In defence of a consumer-led economy -

Why the $5B Trump–BBC fallout is the reckoning the British media has been dodging

Why the $5B Trump–BBC fallout is the reckoning the British media has been dodging -

WPSL Group unveils £1billion blueprint to build a global golf ‘super-group’

WPSL Group unveils £1billion blueprint to build a global golf ‘super-group’ -

Facebook’s job ads ruling opens a new era of accountability for artificial intelligence

Facebook’s job ads ruling opens a new era of accountability for artificial intelligence -

Robots can’t care — and believing they can will break our health system

Robots can’t care — and believing they can will break our health system -

The politics of taxation — and the price we’ll pay for it

The politics of taxation — and the price we’ll pay for it -

Italy’s nuclear return marks a victory for reason over fear

Italy’s nuclear return marks a victory for reason over fear -

The Mamdani experiment: can socialism really work in New York?

The Mamdani experiment: can socialism really work in New York? -

Drowning in silence: why celebrity inaction can cost lives

Drowning in silence: why celebrity inaction can cost lives