Marvel of Nature: How WW3 Could Lead to ‘Superhero’ Humans

Professor Tim Coulson

- Published

- Opinion & Analysis

People could evolve to become superhuman, writes our science and environment correspondent, Professor Tim Coulson. But it could come at a terrible cost: the end of civilisation

In the future, humans could evolve to become hyper-intelligent and have super-senses, incredible physical strength, armadillo-like armour or the ability to fly like a bat. That might sound far-fetched, but I very much doubt that anyone would have predicted that the first animal, which probably looked a bit like a small jellyfish and lived over a half a billion years ago, would eventually evolve into humans. That is probably a bigger leap from humans evolving to become superhuman. Yet we know the first simple animals did eventually evolve to produce all animals alive today, including us. Evolution is a remarkable force.

Instead of evolving into the superheroes of the Marvel franchise perhaps humans might evolve to become less intelligent and weaker. Maybe the film Idiocracy, where humans evolve to become more stupid, is a more realistic future? Can we say anything about what humans might evolve into in the future?

Animals – and plants, bacteria and fungi too – adapt to the environment that they live in. They evolve in response to something, and that something is whatever is killing them or preventing them from breeding. Cheetahs evolved to run fast to catch gazelles and other prey, and if they hadn’t evolved great speed with which to chase down lunch, individuals may have starved to death and the species could have gone extinct. The gazelles they chase also evolved to run quickly to escape death in the jaws of a cheetah. If evolution hadn’t endowed them with great speed, they may have all been eaten and their population would have been doomed to extinction. The cheetah and their gazelle prey are in an evolutionary arms race, evolving together in response to one another. We can work out what will drive evolution in a population by looking at what kills individuals or stops them from breeding and provide an educated guess at the characteristics we might expect to evolve. With no need for speed, humans would be expected to evolve to run more slowly.

We had evolved big brains, intelligence, language, and our physique by about quarter of a million years ago in Africa where we needed to hunt for meat and search for fruit, roots and berries while avoiding become prey to lions and leopards, being killed by other people, or catching a deadly disease. You needed wits, and probably a bit of good fortune, to stay alive long enough to breed.

Nowadays, in the developed world at least, staying alive and reproducing is easy. It does not require strength or agility or the ability to run long distances, search beyond a supermarket shelf for something to eat, or dodge a marauding elephant. The major causes before diseases of old age kick in, is suicide or accident. There is some evidence that genes contribute a little to the likelihood of a person attempting suicide, so given enough time humans may evolve such that suicide becomes less common.

Evolution is also driven by reproduction. In humans, in the West at least, many couples delay having children until they are in their 40s. Many then fail to conceive. This relatively widespread failure to reproduce is likely to select for women who remain fertile for longer. Perhaps in thousands of years’ time, menopause will be a thing of the past.

If an organism doesn’t need a particular trait to survive and reproduce, evolution has a habit of getting rid of it. Fish that live in dark caves lose the ability to see, and birds that live on islands where there are no predators often lose the ability to fly. Given intelligence, strength and agility do not determine how long we will live for or how many children we have, these traits could be lost in time. Perhaps the process has already started. Scientists have estimated our brains are about 8.5% smaller than they were in our ancestors living 5000 years ago. You might say that we are still inventing new things – and we are certainly not stupid – but perhaps we would have discovered these things faster, and without negatively impacting the natural world, if we had their bigger brains.

I can see no reason why we should evolve superhuman abilities if our civilisation continues to make survival and reproduction easy. If things don’t change, I can also see no reason why we should not become less intelligent and less athletic over the coming millennia. However, one of the challenges in predicting what humans will look like in the future is environments change. For example, there were many changes that had to happen for the first animals to evolve into us. We are changing lots of aspects of our environment, and we should not assume that the drivers of natural selection that our populations experience today will be around in a century or millennium’s time. That’s why it is so hard to predict which twists and turn evolution will take.

My guess is our environment will change dramatically at some point when our civilisation collapses. All previous civilisations have collapsed, from ancient Egypt to the Mayans, and there is no reason to suspect ours is any different. Disease, perhaps predators, other people, and starvation would become common forms of death for the survivors of such a catastrophe. Intelligence, cunning, super senses, strength and speed may then become attributes associated with improved survival and reproduction, much as they did in our past on the plains of Africa. Civilisation may select for greater stupidity and sloth, while its demise might lead to superhumans with traits beyond our recognition.

Professor Tim Coulson is a biologist at the University of Oxford, where he has led both the Zoology and Biology departments. He previously headed Population Biology at Imperial College London and held positions at Cambridge University and the Institute of Zoology London. A highly decorated scientist with awards from major institutions including the Royal Society, he has edited leading journals and served on Government advisory boards. His first book for general readers, “A Universal History of Us” (Penguin Michael Joseph), traces the 13.8-billion-year story from the Big Bang to human consciousness and is available to buy on Amazon.

Main image: Courtesy, Keith Pottinger/Pexels

RECENT ARTICLES

-

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament?

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament? -

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth -

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours -

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality -

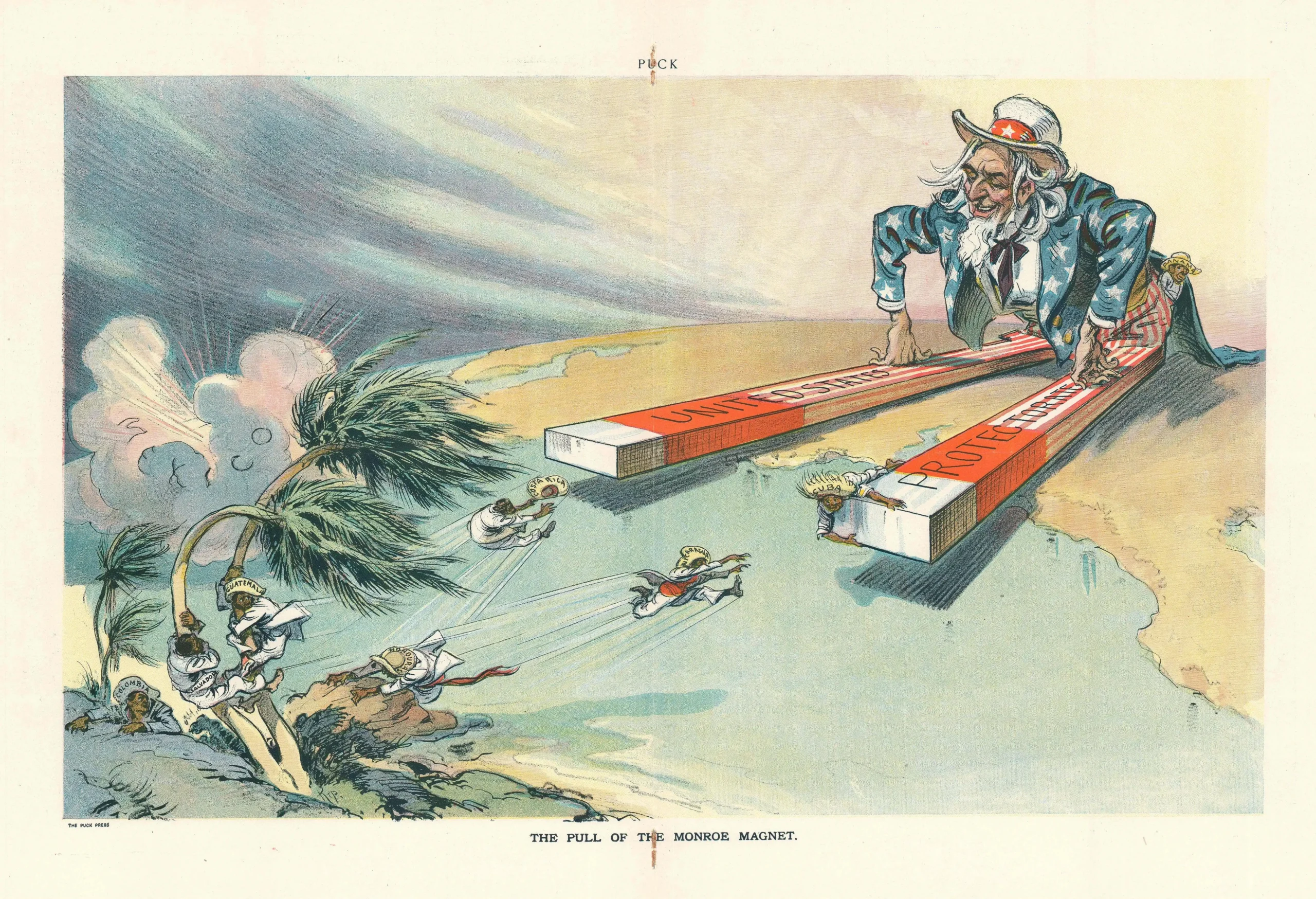

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now -

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day -

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy -

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it -

What if he falls?

What if he falls? -

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world -

Will Trump’s Davos speech still destroy NATO?

Will Trump’s Davos speech still destroy NATO? -

Philosophers cautioned against formalising human intuition. AI is trying to do exactly that

Philosophers cautioned against formalising human intuition. AI is trying to do exactly that -

Life’s lottery and the economics of poverty

Life’s lottery and the economics of poverty -

On a wing and a prayer: the reality of medical repatriation

On a wing and a prayer: the reality of medical repatriation -

Ai&E: the chatbot ‘GP’ has arrived — and it operates outside the law

Ai&E: the chatbot ‘GP’ has arrived — and it operates outside the law -

Keir Starmer, Wes Streeting and the Government’s silence: disabled people are still waiting

Keir Starmer, Wes Streeting and the Government’s silence: disabled people are still waiting -

The fight for Greenland begins…again

The fight for Greenland begins…again -

Failure is how serious careers in 2026 will be shaped

Failure is how serious careers in 2026 will be shaped -

Poland’s ambitious plans to power its economic transformation

Poland’s ambitious plans to power its economic transformation -

Europe’s space ambitions are stuck in political orbit

Europe’s space ambitions are stuck in political orbit -

New Year, same question: will I be able to leave the house today?

New Year, same question: will I be able to leave the house today? -

A New Year wake-up call on water safety

A New Year wake-up call on water safety -

The digital euro is coming — and Europe should be afraid of what comes with it

The digital euro is coming — and Europe should be afraid of what comes with it -

Make boards legally liable for cyber attacks, security chief warns

Make boards legally liable for cyber attacks, security chief warns -

Why Greece’s recovery depends on deeper EU economic integration

Why Greece’s recovery depends on deeper EU economic integration