Jury on trial: why scrapping the people’s voice risks the collapse of justice

Dr Raj Joshi

- Published

- Opinion & Analysis

For nearly a thousand years, juries have been central to justice, giving ordinary people a say in life-changing decisions. Now, proposals to sideline them in favour of judges and magistrates risk undermining fairness and public confidence. Barrister and civil rights campaigner Raj Joshi warns that true reform lies in fixing an underfunded and fragile system, not in abolishing the jury

From 12 Angry Men and To Kill a Mockingbird through to My Cousin Vinny, courtroom dramas are a mainstay of movies and are a part of popular culture.

Audiences are gripped by the evidence unfolding on both sides and try to second-guess and wait anxiously for the verdict from the jury.

Trial by jury is far from a modern concept. Its roots lie in 12th-century England, when Henry II’s Assize of Clarendon (1166) ordered twelve local men to identify suspected criminals under oath — a forerunner of today’s jury system.

The Magna Carta of 1215 enshrined those principles more firmly. Among its clauses were that no man could be put on trial on one person’s word alone; no free man could be imprisoned or dispossessed without the judgment of his peers or the law of the land; and that justice could not be sold, denied or delayed.

The importance of these basic aspects of justice is not to be underestimated as they have formed the cornerstone of constitutions and declarations of rights throughout the world and are enshrined in democratic societies as fundamental safeguards for the people.

In England, the celebrated Bushell’s Case (1670) established the independence of juries. Quakers William Penn — later founder of Pennsylvania — and William Mead were charged at the Old Bailey with unlawful assembly and disturbing the peace.

Their real offence was preaching ideas that clashed with Church of England doctrine. While the jury accepted the pair had preached, it refused to brand the act unlawful. The jury found Penn and Mead not guilty. Furious, the judge ordered the jurors locked up without “meat, drink, fire or tobacco” until they changed their minds.

Penn protested: “What hope is there of ever having justice done, when juries are threatened, and their verdicts rejected?” The jury held firm and returned not guilty verdicts. When foreman Edward Bushell refused to pay the judge’s fine, he was jailed but appealed. The Court of Common Pleas freed the jurors and, in doing so, cemented the principle of jury independence. A plaque at the Old Bailey still marks Bushell’s Case, honouring the “courage and endurance of the jury”.

More recently, 69-year-old Trudy Warner stood silently outside a court hearing a climate activist trial, holding a placard that read: “Jurors, you have an absolute right to acquit a defendant according to your conscience.” She spoke to no one, acting only as a “human billboard”.

The Solicitor General pursued her for contempt of court, but the High Court dismissed the case in strong terms. Judges said it was “fanciful to suggest that Ms Warner’s behaviour falls into this category of contempt”, noting her sign merely echoed the sentiments of the Bushell plaque in the Old Bailey. As Lord Bingham put it in R v Wang — a case where the trial judge wrongly directed a jury to convict — “decisions on the guilt of defendants charged with serious crime should rest with a jury of lay people, randomly selected, and not with professional judges.”

But unfortunately, despite the supposed sanctity of juries, there are now proposals to wipe out jury trial for most offences.

The Leveson Report makes recommendations for either judges alone or judges sitting with magistrates to conduct most cases. If implemented, such reforms would have stripped juries of their role in the majority of trials, leaving questions of guilt or innocence in the hands of professionals rather than peers.

Law Society research, published in 2022 stated that it would take 120 years before the judiciary represents the community upon which it sits in judgement. As an example, black judges comprised just 1.09% of the judiciary in 2022, up from only 1.02% in 2014.

At that rate of progress, it would be 2149 until the number of black judges would represent the black community. In a Manchester University report entitled “Racial Bias and the Bench”, researchers found that “racial bias plays a significant role in the justice system”.

Perhaps more alarmingly, government statistics show “the conversion rate from application to judicial appointment for Asian and Black candidates was estimated to be 37% and 75% lower respectively than for successful white candidates”.

It will also take another 10 years before half of the judiciary are female. The Leveson report does not deal with any of the perceived bias of the judiciary in a multi-layered and inclusive society, restricting itself to process and procedural reform.

The Politics of the Judiciary by JAG Griffith argued some time ago that most judges come from a white, male, public school, Oxford or Cambridge background. The consequences of trial by a jury as opposed to judges are therefore obvious: would you want to be tried by people from your community or just one judge or a judge and two magistrates?

The problem is not that juries reach unreliable verdicts, or that the system of trial by one’s peers is failing. As the Bar Council, Law Society and Criminal Bar Association have all pointed out, the real difficulties lie elsewhere: in underfunded courts, chronic delays, a shortage of judges and lawyers, and outdated procedures. It is these pressures on the justice system, rather than the quality of juries’ decisions, that have fuelled calls to reduce their role.

The Ministry of Justice figures show a record Crown Court backlog of more than 76,957 cases, meaning some trials will not be heard until 2029.

There are also 310,304 outstanding cases in the magistrates’ court.

The consequent wait for victims, witnesses and defendants means fading memories, triggered trauma, delayed justice, and the death of public confidence.

Plans to divert thousands of cases carrying less than two years’ imprisonment, to cut the length of complex trials by removing juries, and to push more guilty pleas with sentence discounts of up to 40% — with defendants serving only half that term — risk putting efficiency ahead of fairness and could erode public trust in the system.

For those who are involved directly in a trial, confidence, especially in sensitive sexual cases is justifiably low and it is not just about the outcome but the transparency of the procedure and involvement in life-changing decisions.

It is one thing accepting the decision of a jury, but quite another to accept the decision of a judge.

In practice, the proposed “Crown Court Bench Division” does not exist — nor do the judges, magistrates or facilities to run it. Diverting cases from the Crown Court to this non-existent body, without new resources, would achieve little.

What is needed is root-and-branch reform with proper investment, not the abolition of juries. The entire machinery of justice — from court staffing and legal aid to case management and technology — should be examined to ensure each part is necessary, effective and fit for purpose.

The Ministry of Justice has a budget of £13.8 billion, with the Crown Prosecution Service alone costing £751.5 million. Yet for all this money, what does the public actually receive in terms of justice delivered? More importantly, what does the victim gain in terms of protection and redress, and what does the defendant gain in terms of a fair and timely trial? Efficiency is vital, but the real question is whether it is being pursued at the expense of fairness.

Trial by jury is not just a relic of Magna Carta but the people’s guarantee of fairness, a safeguard that allows them to trust the system and hold the state to account.

Leveson’s reforms may promise efficiency, but they do not guarantee legitimacy. Shifting the Crown Court’s workload does nothing to address underfunding or the fragility of the system, and tackles a deep crisis in only the most superficial way.

The public must be at the heart of justice, because the system exists to serve the people, not the people to serve the system.

Sacrificing juries will not stop the system from collapsing. As William Penn warned: “You are Englishmen, mind your privilege, give not away your right.”

Read more: Raj Joshi recently warned of similar dangers to judicial independence in his article, The US Supreme Court just ripped up the Fourteenth Amendment. Britain should be paying close attention.

Raj Joshi is a senior barrister and former chair of the Society of Black Lawyers. He was named among the Top 10 Asian Lawyers in the UK and the 100 Most Influential Asians in the UK. He has advised the Judicial Studies Board, and served as an adjudicator, campaigner, and legal advisor across multiple institutions tackling race, justice, and equality.

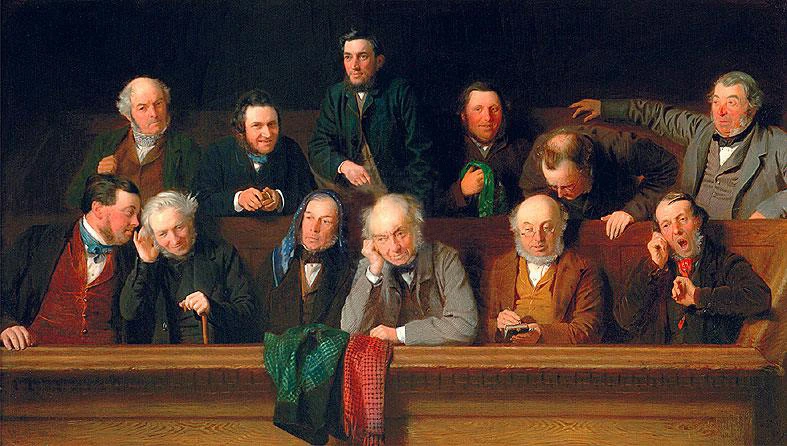

Main image: “The Jury” by John Morgan (1861), a satirical painting that captures the mixed expressions and personalities of jurors — a reminder of the human element at the heart of justice. Photo: Wikipedia (Commons Licence)

RECENT ARTICLES

-

The era of easy markets is ending — here are the risks investors can no longer ignore

The era of easy markets is ending — here are the risks investors can no longer ignore -

Is testosterone the new performance hack for executives?

Is testosterone the new performance hack for executives? -

Can we regulate reality? AI, sovereignty and the battle over what counts as real

Can we regulate reality? AI, sovereignty and the battle over what counts as real -

NATO gears up for conflict as transatlantic strains grow

NATO gears up for conflict as transatlantic strains grow -

Facial recognition is leaving the US border — and we should be concerned

Facial recognition is leaving the US border — and we should be concerned -

Wheelchair design is stuck in the past — and disabled people are paying the price

Wheelchair design is stuck in the past — and disabled people are paying the price -

Why Europe still needs America

Why Europe still needs America -

Why Europe’s finance apps must start borrowing from each other’s playbooks

Why Europe’s finance apps must start borrowing from each other’s playbooks -

Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes

Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes -

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others -

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again -

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart?

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart? -

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing -

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage -

The limits of good intentions in public policy

The limits of good intentions in public policy -

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament?

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament? -

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth -

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours -

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality -

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now -

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day -

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy -

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it -

What if he falls?

What if he falls? -

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world