The US Supreme Court just ripped up the Fourteenth Amendment. Britain should be paying close attention

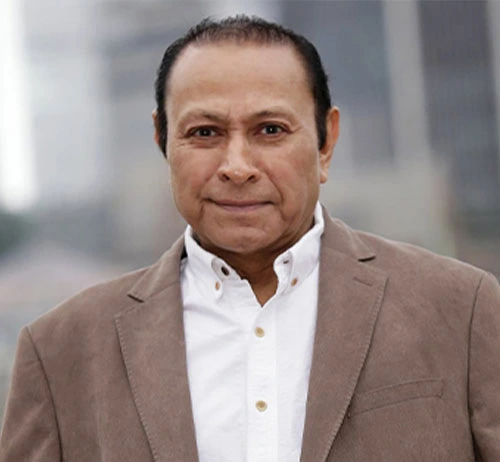

Dr Raj Joshi

- Published

- Opinion & Analysis

The U.S. Supreme Court has just gutted one of the most fundamental constitutional protections in American law: the right to citizenship and equal protection under the Fourteenth Amendment. In doing so, it handed the president unprecedented power to act without effective judicial oversight. Britain, and every democracy that values the rule of law, should be paying very close attention, warns barrister and civil rights campaigner, Raj Joshi

In 1868, the United States ratified the Fourteenth Amendment, a constitutional safeguard introduced to ensure that anyone born on American soil is a U.S. citizen, and that all citizens are guaranteed equal protection under the law.

It was written to overturn Dred Scott v. Sandford, the Supreme Court’s infamous 1857 ruling which held that Black Americans, whether enslaved or free, could never be citizens and had no legal standing in federal court. That decision, which declared that people of African descent were “not included, and were not intended to be included” in the word “citizens” in the Constitution, helped ignite the Civil War. The Fourteenth Amendment was drafted to make sure no court could ever say such a thing again.

More than 150 years later, the Supreme Court has taken a wrecking ball to that protection.

On 28 June, the same court ruled that if a president issues an unlawful or unconstitutional policy — such as one denying citizenship to an entire class of people, as was the case in Dred Scott — a federal judge can no longer block that policy nationwide.

The case, Trump v. CASA, concerned an executive order issued by Donald Trump that tried to deny birthright citizenship to children born in the U.S to undocumented migrants. Three federal district courts said the policy violated the Fourteenth Amendment and blocked it nationwide. But the Trump administration appealed, arguing that judges had no power to issue national rulings, even when the policy in question was found to be unconstitutional.

The Supreme Court sided with Trump. It did not say the policy was legal. It simply said judges had no authority to stop it being used across the country. That means if a president introduces a policy that breaks the law — by, for example, removing citizenship from children born in the U.S. — and one judge strikes it down, the policy can still be enforced everywhere else in the country. Or to put it another way: the very idea of equal protection under the law has been reduced to geography and luck.

We’ve already seen the consequences of this approach. In Whole Woman’s Health v. Jackson, the Court refused to block a Texas law that effectively banned abortion, even after multiple appeals. The result was a legal loophole that stripped women of a constitutional right in one part of the country while preserving it elsewhere.

The uneasy relationship between an independent judiciary and political power has long been a pressure point in any democracy. Where judges are appointed to serve political interests rather than uphold the law, it is the public — not the politicians — who suffer.

History has repeatedly shown the danger of an executive that operates without limits.

Julius Caesar famously defied the Roman Senate, refusing to disband his army and face charges. Instead, he crossed the Rubicon, triggered a civil war, and brought an end to the Roman Republic. Autocracy followed.

In 17th-century England, King Charles I routinely imprisoned his opponents without trial and ignored court rulings, using royal prerogative to bypass Parliament. The 1628 Petition of Right tried to curb these abuses — particularly arbitrary imprisonment and taxation without consent — but the King simply dissolved Parliament and ruled by decree. Civil war followed. Charles was tried for tyranny and executed.

In 1933, Germany’s Enabling Act gave Adolf Hitler the power to pass laws without Reichstag approval. He used it to dismantle every democratic institution in the country and declare himself Führer.

More recently, in Brazil, Jair Bolsonaro announced in 2021 that he would not obey Supreme Court orders. He threatened to impeach judges and rewrite the constitution to limit judicial power. His supporters, including military and police factions, were mobilised to intimidate the Court directly. Bolsonaro ultimately lost the election — but even in exile in Florida, he continued to reject the result. In a twist of history, Brazil’s Supreme Court has since ruled unanimously that he must stand trial for a range of offences, from incitement to attempted coup d’état.

Thankfully, courts in many countries still have the authority — and the independence — to step in when their governments overreach.

In the UK, for example, British judges are not political appointees and their decisions are not shaped by partisan loyalties.

A recent example came during the Brexit crisis. When Boris Johnson wanted to force his withdrawal agreement through, he advised the Queen to prorogue Parliament — effectively shutting it down — for five weeks in the run-up to the deadline. The move would have left MPs without time to debate or scrutinise the deal.

The Supreme Court stepped in. In R (Miller) v. The Prime Minister, Baroness Hale, delivering a unanimous ruling, said: “The decision to advise Her Majesty to prorogue Parliament was unlawful because it had the effect of frustrating or preventing the ability of Parliament to carry out its constitutional functions without reasonable justification.”

Some ministers, including Jacob Rees-Mogg, reportedly called it a “constitutional coup”. But in reality, the court had simply reaffirmed the principle that in a democracy, it is Parliament — not the executive — that has the final say.

That ruling was not an anomaly. Time and again, UK courts have stepped in to ensure that ministers remain within the limits of the law.

In a case involving GCHQ, the government’s intelligence and cyber agency, the court found that employees should have been consulted before the government imposed a ban on union membership. While it accepted the national security grounds, it made clear that the process still required proper scrutiny.

In another instance, the Supreme Court blocked the Attorney General’s attempt to veto a tribunal’s decision to release memos written by Prince Charles (as he then was). The court ruled that ministers could not override judicial decisions at their convenience, and that when a court orders disclosure, transparency must follow.

And when the government introduced fees for employment tribunal claims — resulting in a sharp fall in the number of cases — the court intervened again. It held that such charges were unconstitutional, as they denied people access to justice, which the court affirmed as a “fundamental right”.

But the Trump ruling shows how easily that balance of power can unravel. When courts are stripped of the authority to uphold constitutional rights, the executive is left to operate unchecked. Legal protections become inconsistent, court rulings lose authority, and the rule of law — which relies as much on compliance and respect as legislation — begins to weaken.

Public trust in justice depends on the belief that no one is above the law. When governments dismiss or sidestep judicial decisions, that trust quickly erodes. In countries like Brazil, political attacks on the judiciary have escalated into full constitutional crises. History offers no shortage of warnings — what matters is whether we recognise them in time.

The Trump v. CASA case is a reminder of how fragile constitutional rights can become when they are no longer defended by strong, independent courts. Britain has, so far, avoided the politicisation of its judiciary. That independence must be safeguarded. The rights we rely on — from justice in the courts to accountability in government — depend on it.

Raj Joshi is a senior barrister and former chair of the Society of Black Lawyers. He was named among the Top 10 Asian Lawyers in the UK and the 100 Most Influential Asians in the UK. He has advised the Judicial Studies Board, and served as an adjudicator, campaigner, and legal advisor across multiple institutions tackling race, justice, and equality.

Main image: Malcolm Hill/Pexels

RECENT ARTICLES

-

The era of easy markets is ending — here are the risks investors can no longer ignore

The era of easy markets is ending — here are the risks investors can no longer ignore -

Is testosterone the new performance hack for executives?

Is testosterone the new performance hack for executives? -

Can we regulate reality? AI, sovereignty and the battle over what counts as real

Can we regulate reality? AI, sovereignty and the battle over what counts as real -

NATO gears up for conflict as transatlantic strains grow

NATO gears up for conflict as transatlantic strains grow -

Facial recognition is leaving the US border — and we should be concerned

Facial recognition is leaving the US border — and we should be concerned -

Wheelchair design is stuck in the past — and disabled people are paying the price

Wheelchair design is stuck in the past — and disabled people are paying the price -

Why Europe still needs America

Why Europe still needs America -

Why Europe’s finance apps must start borrowing from each other’s playbooks

Why Europe’s finance apps must start borrowing from each other’s playbooks -

Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes

Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes -

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others -

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again -

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart?

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart? -

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing -

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage -

The limits of good intentions in public policy

The limits of good intentions in public policy -

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament?

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament? -

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth -

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours -

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality -

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now -

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day -

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy -

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it -

What if he falls?

What if he falls? -

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world