The limits of good intentions in public policy

Harry Margulies

- Published

- Opinion & Analysis

Although public systems are often created with the best of intentions and rooted in compassion, they begin to struggle when those who design them fail to consider how real people respond to incentives, boundaries and opportunity. Drawing on examples from tax law, welfare, asylum policy and international governance, Harry Margulies argues that reluctance to confront predictable misuse early on leads to public distrust, political backlash and reforms far harsher than steady enforcement would ever have required

Compassion sits at the heart of many of the systems on which civil society relies. You can see it in tax reliefs designed to encourage businesses to grow, in welfare provisions created to protect families during difficult times, in asylum rules written to safeguard people fleeing danger, and in international agreements intended to moderate the behaviour of powerful states. Generally speaking, such systems begin as moral expressions that are turned into practical rules, procedures and institutions. They only continue to function as intended when that moral purpose is matched by a clear understanding of how real people respond to incentives, opportunities and limits.

Those who design these systems often write the rules in the hope that most participants will behave in line with the spirit in which those rules were drafted. In practice, behaviour tends to follow incentives with remarkable consistency. When an advantage exists within the wording of the law, people will find it and use it. What later comes to be described as “abuse” often began as a perfectly rational response to rules that were not defended carefully enough at the start. When oversight is slow or hesitant because of kindness or caution, space opens for practices that were never part of the original intention. Public trust then drains away quietly, not because compassion was misguided, but because realism was missing when the system was first built.

The long-running dispute between the European Commission and Apple in Ireland shows how this process unfolds in the real world. For many years Apple reportedly routed European profits through Irish subsidiaries in ways that produced an extremely low effective tax rate. These arrangements were lawful under the rules as they existed at the time. They followed the incentives created by a tax framework designed to attract multinational companies. In 2016 the Commission ruled that Ireland had granted illegal state aid and ordered the recovery of €13 billion, a decision later upheld by the European Court of Justice. Much of the public discussion focused on whether the outcome was morally acceptable. The more revealing point lay in the structure of the system itself, which had made this behaviour entirely logical from a corporate perspective. What later looked like manipulation had once been welcomed as evidence that the policy was working.

A similar pattern appears in the administration of welfare. In the United Kingdom the Department for Work and Pensions oversees Universal Credit, a system on which millions of people depend for essential support. The department’s own statistics show levels of fraud and error which, while proportionally small, translate into large sums of money and significant political attention. Administrators move cautiously because they know that overzealous enforcement can harm people who genuinely need help. That understandable caution allows misuse to settle into the background. Over time, what starts as occasional exploitation begins to feel routine to some claimants, strengthened by the belief that intervention is unlikely. Officials, aware of how closely their decisions are scrutinised and lacking strong political backing for firm action, often choose to avoid confrontation. Whistleblowing is discouraged. By the time reform gathers political momentum, the proposed changes tend to fall heavily on many who never sought to exploit the system, because patience has already worn thin.

Asylum policy brings the same structural difficulty into sharper focus. The 1951 Refugee Convention, overseen by the UNHCR, commits countries to protect people fleeing persecution. That moral obligation remains clear and compelling. Difficulties arise when the practical benefits attached to asylum, such as accommodation and support, become an incentive in themselves for some. Applications can rise more quickly than the system can process them, and temporary arrangements such as hotel accommodation expand rapidly in response.

In 2024, UK asylum claims exceeded 100,000 and a large backlog awaited decisions. Stories about costs, contracts and individual cases circulate widely and shape how the public sees the system. As it becomes harder for people to distinguish between those seeking safety and those seeking opportunity, consent begins to weaken among the taxpayers who fund the system. The silent majority who sustain it begin to question whether it is still working as intended. At the same time, research by organisations such as the Mental Health Foundation shows the severe trauma and anxiety experienced by genuine asylum seekers trying to navigate an overstretched process. Compassion and realism sit side by side here, and reluctance to deal with misuse early risks provoking a backlash against migration as a whole rather than against the growing number who bend the rules.

A different kind of failure can be seen in the Windrush scandal. In this case, immigration enforcement operated rigidly, supported by incomplete data and warnings that went unheeded. Lawful residents were detained and deported because the system did not reflect the reality of their lives. Public confidence fell sharply, apologies followed, and compensation schemes were introduced. The lesson lay in the gap between rules and lived experience, and in the damage that occurs when realism is absent from enforcement.

The same dynamic can be seen at an international level. The United Nations Human Rights Council exists to promote and defend global standards of human rights. Its membership has included states with poor records at home, leading to sustained criticism from organisations such as Human Rights Watch. When participation in a moral framework does not require adherence to its principles, the credibility of that framework weakens and the willingness of others to take it seriously declines.

Across all of these examples, the same pattern becomes unmistakable. Systems conceived in empathy and sustained by good intentions begin to struggle, and at times to unravel, when they rely on goodwill alone to hold them together. Reluctance to confront predictable misuse at an early stage sets in motion a self-reinforcing cycle in which exploitation gradually becomes seen as normal, while those who continue to follow the rules shoulder a growing share of the burden. Administrators, wary of appearing severe or unsympathetic, hesitate to press for reform. In this atmosphere, a subtle shift in attitude takes hold: behaviour that was once seen as exceptional becomes justified on the grounds that others are doing the same, and a sense of entitlement quietly replaces the notion of eligibility. Trust, once eroded, drains away with surprising speed, and the political responses that follow are often abrupt, punitive and far harsher than the measured corrections that would have sufficed had action been taken earlier.

The lasting strength of compassionate systems depends on recognising how incentives operate in practice, setting firm boundaries from the start, and applying oversight consistently rather than only when problems become impossible to ignore. Empathy and realism need to work together in institutional design. When one is present without the other, disappointment follows for those the system was meant to help and frustration grows among those expected to support it.

For systems of this kind to endure over time, they depend upon early and consistent enforcement, boundaries that are clearly defined and capable of being upheld in practice, robust administrative and judicial oversight, and the moral resolve to exclude those who seek to exploit the rules so that legitimacy can be preserved for those who genuinely depend upon protection.

Societies that anchor compassion in a clear understanding of how people actually behave are able to build institutions that retain public trust, while those that rely on goodwill alone often discover, too late, that neglecting realism leads first to institutional weakening and then to corrective measures that are far more severe than they ever needed to be.

Harry Margulies is a journalist, author, commentator, and public intellectual whose work interrogates religion, politics, and morality with sharp wit and fearless clarity. A second-generation Holocaust survivor, he was born in Austria and spent time in an Austrian refugee camp before moving to Sweden. Educated by Orthodox rabbis throughout his childhood, he ultimately abandoned faith in his teens—a journey that has shaped his lifelong commitment to secularism, critical thinking, and freedom of expression. His latest book, Is God Real? Hell Knows, has been described by ABBA’s Björn Ulvaeus as “funny, sharp, and unafraid.”

READ MORE: ‘Life’s lottery and the economics of poverty‘. A child’s prospects can depend heavily on the country they are born into and the support it provides. Harry Margulies examines how these early “wins” and “losses” affect opportunity later in life.

Do you have news to share or expertise to contribute? The European welcomes insights from business leaders and sector specialists. Get in touch with our editorial team to find out more.

Main image: Bhullar/Pexels

RECENT ARTICLES

-

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament?

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament? -

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth -

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours -

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality -

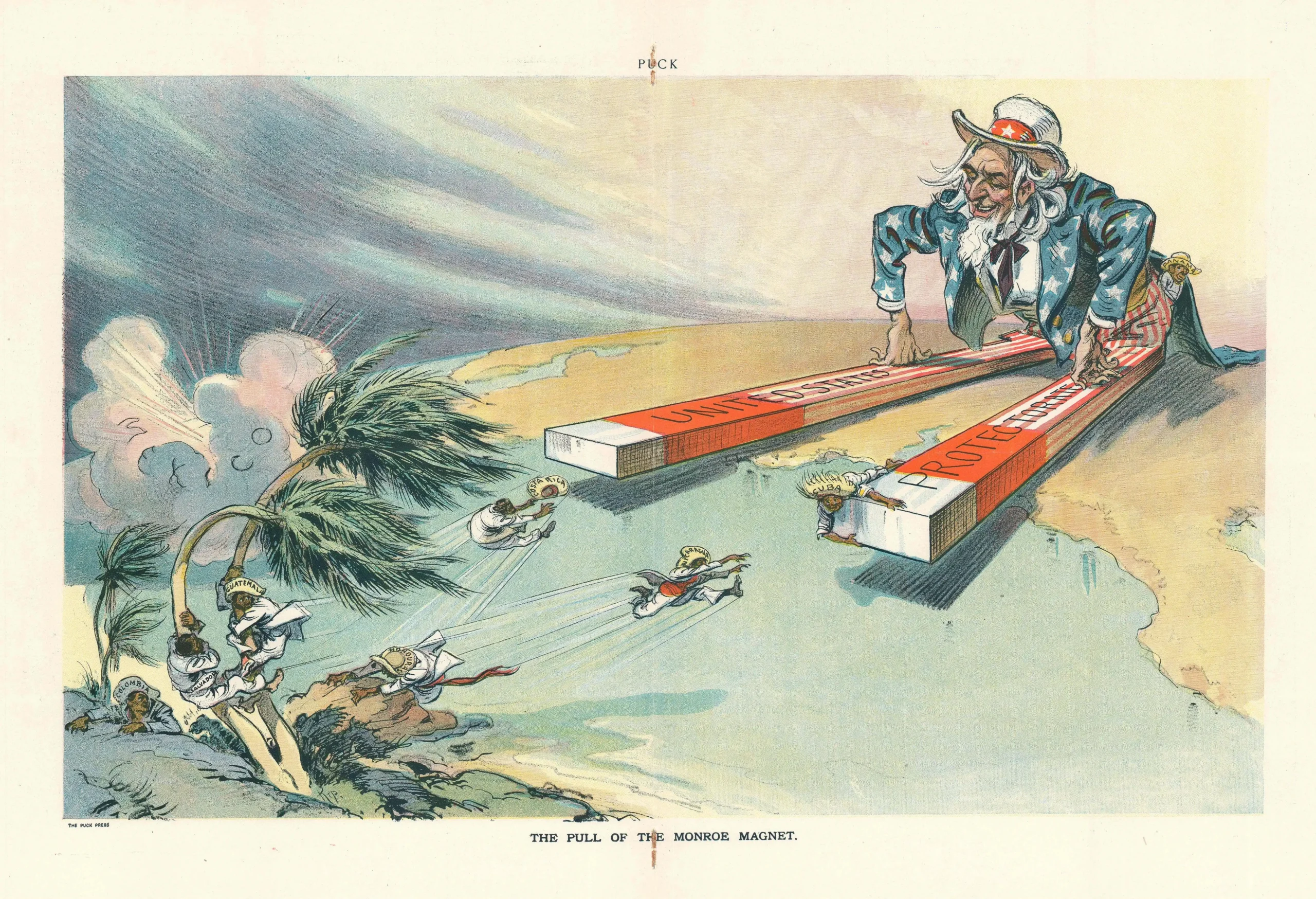

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now -

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day -

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy -

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it -

What if he falls?

What if he falls? -

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world -

Will Trump’s Davos speech still destroy NATO?

Will Trump’s Davos speech still destroy NATO? -

Philosophers cautioned against formalising human intuition. AI is trying to do exactly that

Philosophers cautioned against formalising human intuition. AI is trying to do exactly that -

Life’s lottery and the economics of poverty

Life’s lottery and the economics of poverty -

On a wing and a prayer: the reality of medical repatriation

On a wing and a prayer: the reality of medical repatriation -

Ai&E: the chatbot ‘GP’ has arrived — and it operates outside the law

Ai&E: the chatbot ‘GP’ has arrived — and it operates outside the law -

Keir Starmer, Wes Streeting and the Government’s silence: disabled people are still waiting

Keir Starmer, Wes Streeting and the Government’s silence: disabled people are still waiting -

The fight for Greenland begins…again

The fight for Greenland begins…again -

Failure is how serious careers in 2026 will be shaped

Failure is how serious careers in 2026 will be shaped -

Poland’s ambitious plans to power its economic transformation

Poland’s ambitious plans to power its economic transformation -

Europe’s space ambitions are stuck in political orbit

Europe’s space ambitions are stuck in political orbit -

New Year, same question: will I be able to leave the house today?

New Year, same question: will I be able to leave the house today? -

A New Year wake-up call on water safety

A New Year wake-up call on water safety -

The digital euro is coming — and Europe should be afraid of what comes with it

The digital euro is coming — and Europe should be afraid of what comes with it -

Make boards legally liable for cyber attacks, security chief warns

Make boards legally liable for cyber attacks, security chief warns -

Why Greece’s recovery depends on deeper EU economic integration

Why Greece’s recovery depends on deeper EU economic integration