‘I was bullied into submission’: how Huw Montague Rendall fought back to become opera’s next superstar

Dr Stephen Simpson

- Published

- Lifestyle

At just 30, Huw Montague Rendall is already one of opera’s most commanding young baritones, a regular presence at Covent Garden, Paris and the great European festivals. In this exclusive interview with Dr Stephen Simpson, he speaks candidly about the bullying that marked his early career — and how it forged the resolve, discipline and focus that now define a modern maestro

Huw Montague Rendall looks away when I refer to him as a natural singer. I can’t be sure, but I strongly suspect he is rolling his eyes.

It was meant as a compliment; Huw is, after all, one of the world’s most in-demand baritones with a voice that has become familiar in flagship productions across Europe at Zurich, Glyndebourne and Covent Garden. He is also, increasingly, recognised beyond the opera house. Last year his debut album Contemplation (Erato) drew widespread critical praise, with reviewers singling out the “velvet-toned, nuanced” quality of his singing and the range he brings to repertoire from Mahler and Duparc to Gounod and Korngold.

But as I soon discover, talent is a starting point rather than the explanation for an astonishingly successful, and at times challenging, career. “Just because you’re ‘a natural’ at something doesn’t mean you work any less hard than someone who isn’t,” he tells me this week. “In fact, it undermines all the work I do on my own, the work I did at college, the work I do with my teachers and on stage every night.”

He is, of course, quite right. I work with a wide range of performers, sports personalities and public figures, and the pattern is always the same: ability may open the door, but the standard they reach comes from years of disciplined, and usually unseen, hard graft.

If you have somehow missed him, Huw has sung Papageno in Die Zauberflöte, Guglielmo in Così fan tutte, Schaunard in La Bohème, Harlequin in Ariadne auf Naxos and Malatesta in Don Pasquale. He is currently alternating between two casts of The Magic Flute at Covent Garden. His rapid ascent is even more striking when placed in context: he sang his first Don Giovanni only last year in Rouen, where the orchestra later joined him for his recording sessions with conductor Ben Glassberg.

He has built that career unusually fast. In the past few seasons he has made widely acclaimed debuts at the Royal Opera House, Lyric Opera of Chicago, the Paris Opera, the Aix-en-Provence Festival and at Salzburg and Glyndebourne, earning a reputation as one of the most compelling young baritones working today. Last year he won the Voice and Ensemble category at the Gramophone Classical Music Awards, not long after his role debut as Billy Budd at the Wiener Staatsoper. The momentum continues. In the 2025/26 season he returns to Covent Garden before new appearances at the Gran Teatre del Liceu, the Paris Opera, the Vienna State Opera and the Opéra de Monte-Carlo, alongside concerts with the Berliner Philharmoniker, the Hallé and the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra.

Born into a musical family — his mother the mezzo-soprano Diana Montague and his father the tenor David Rendall — he studied at the Royal College of Music under Russell Smythe after early instruction from both parents and Philip Doghan. His early recognition included the John Christie Award at Glyndebourne, a summer as a Jerwood Young Artist, and a place on the Salzburg Festival’s Young Artist Programme before joining Zurich’s International Opera Studio.

His formative years of disciplined work were made harder thanks to an unforgiving industry that demands perfection and yet offers little protection. Early in his career, he reveals, he was subjected to intimidation by senior colleagues. “I was bullied into submission,” he tells me. “It taught me that in this business you are on your own. You have to stand up for yourself, because everyone else is standing up for themselves.”

Huw, who is still only 30, refuses to identify the production or the people involved. But as we speak, it becomes clear that the experience, wherever it was, took its toll. The pressure crept into every part of his working life, unsettling him mentally and hitting his body with the same force. “Usually with stress comes acid reflux, which burns your vocal cords,” he says. “I had terrible, terrible bouts of this when I was going through that.”

Despite the psychological and physical toll, Huw stayed and completed the engagement. “Sometimes at the beginning of your career you have to be the whipping boy,” he says. “At the time I didn’t know I should have folded my score and walked out that door. But the change only comes when you decide it changes.”

What happened during that production was, he explains, a blunt education in how rehearsal rooms can still operate. Opera houses market themselves as international institutions with world-class standards, yet the structure inside many rehearsal studios remains informal, hierarchical and largely unregulated. Conductors and directors can dominate without challenge, while freelancers, especially young singers, have limited protection and no formal reporting routes. A culture of silence, he says, allows poor behaviour to continue.

“You have someone shouting at you in a rehearsal and everyone buries their heads in their laps,” he recalls. “You look around and think, okay, well, I’m on my own.”

He began to understand that self-preservation must be an active part of the job, and that managing his own emotions was part and parcel of the trade. “Worrying and stress is not conducive to a good artist,” he says. “Sometimes we need to be a little bit burned in the pan in order to thicken the skin.”

Huw also learned to recognise patterns in how authority is used and abused. “It’s all for power,” he says. “It’s all to show dominance in front of a room full of 150 people.” The lesson was not about avoiding conflict but about asserting boundaries. “You have to stand up for yourself, because the people around you are standing up for themselves.”

He describes confidence as something that shifts from day to day. “Some days I think I can’t do this and then some days I’m like, okay, you can,” he says. Nerves are routine for singers, and he has seen them in artists at every level. “People would be very, very, very famous singers throwing up in their dressing rooms before they’d go on stage because they were so nervous. Every night.”

For him, the pressure comes from the nature of the work. A performance exposes the singer directly to the room in front of them. “You’re sharing a part of yourself with the audience,” he says. The voice either supports that or it does not, and he feels the difference immediately. “I am my biggest fan and my biggest critic,” he says. “When it’s right it’s great. When it’s wrong it’s awful.”

To stay centred, Huw keeps his circle deliberately small: his fiancée Lily, his mother, his agent and a handful of coaches who know his voice as well as he does. Their advice carries weight because it comes from people who understand the work rather than judge it from the outside. Even with that support, he says the hardest part is managing his own standards. “Trying not to see only the negative is one of the hardest things to balance.”

Huw has, over time, developed systems that protect his voice and maintain consistency. Rest is the non-negotiable foundation, he says, as is preparation. “I will usually get to the theatre an hour before,” he says. “Warm up my voice, get into the space, drink a cup of tea, go through my words.” Everything is designed to create steadiness and reduce friction.

The schedule at Covent Garden has forced him to be even more disciplined. The Magic Flute is running with two casts, and rehearsals fall on the days between performances. Recovery time is tight. “I need to stay fit and healthy but also need to rehearse with the other cast between show days,” he says. The priority, for him, is obvious. “You need to make sure you’re fit for a performance in front of 2,500 paying audience members.”

Of all the things he has learned, he says the one that matters most is emotional clarity. “If I’m honest with myself, the audience will feel it,” he says. That principle guides the way he sings, rehearses and teaches. It is the thread that connects the early setbacks with the successes that followed. And as he gets ready for another night on stage, it remains the rule he trusts.

Dr. Stephen Simpson is an internationally acclaimed mind coach, TV and radio presenter, hypnotherapist, TEDx speaker, bestselling author, business consultant, and Fellow of the Royal Society of Medicine. With nearly 40 years as a practicing physician and extensive experience in elite performance coaching, mental health, hypnosis, and NLP, he has worked with top athletes on the PGA European Golf and World Poker Tours. Dr. Simpson holds an MBA from Brunel University and has served as Regional Medical Director for Chevron, contributing to global health initiatives with leaders like Bill Clinton and Bill Gates. He hosts popular shows such as Zen and the Art of NLP, and his YouTube channel boasts over 260 videos and 350,000 views. His latest book, The Psychoic Revolution, encapsulates his innovative methods for achieving peak performance.

READ MORE: ‘The many lives of Professor Michael Atar‘. From paediatric dentistry to sepsis technology, psychotherapy and social innovation, Professor Michael Atar has built a career that refuses to stay in one lane. The European’s Dr Stephen Simpson meets the man whose work spans medicine, physics, mental health and community life.

Do you have news to share or expertise to contribute? The European welcomes insights from business leaders and sector specialists. Get in touch with our editorial team to find out more.

Main image, courtesy Simon Fowler

RECENT ARTICLES

-

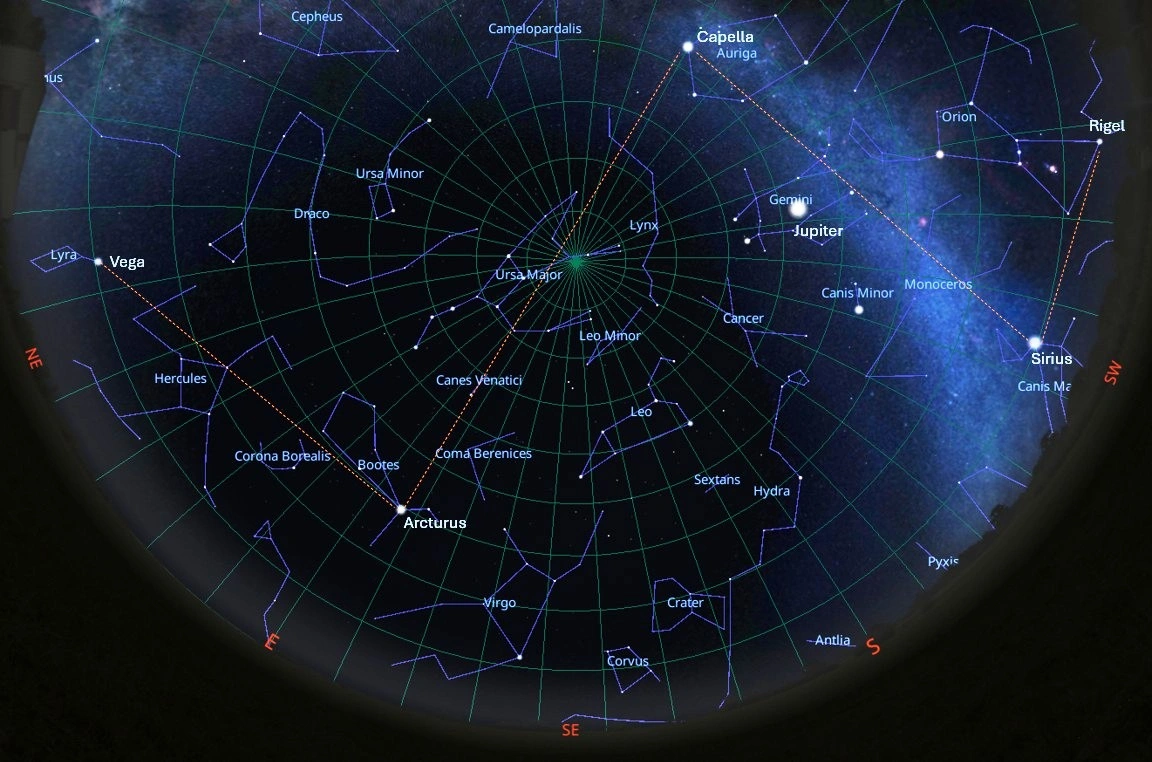

March stargazing guide: the brightest stars to spot this spring

March stargazing guide: the brightest stars to spot this spring -

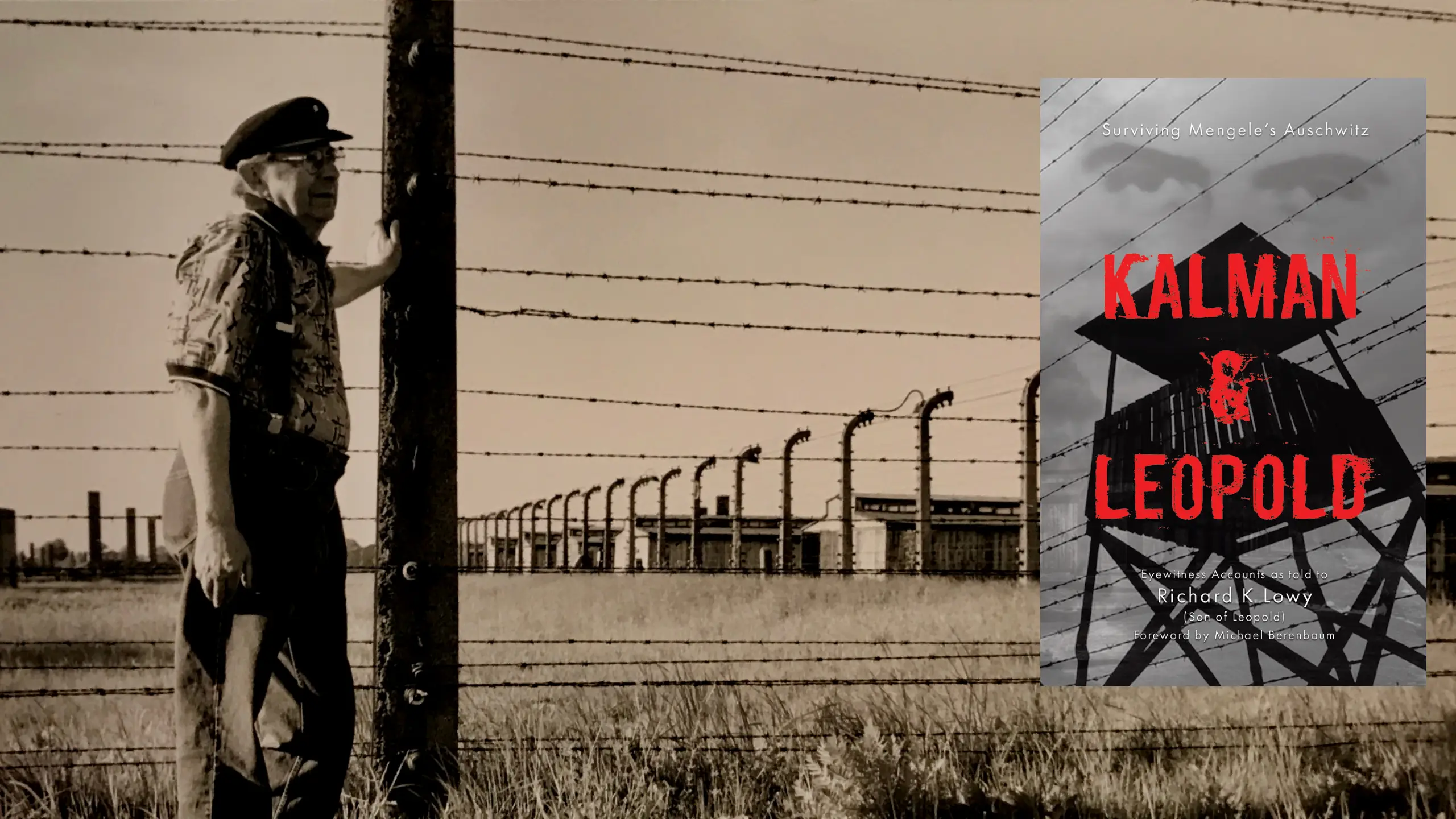

The European Reads: Kalman & Leopold: Surviving Mengele’s Auschwitz

The European Reads: Kalman & Leopold: Surviving Mengele’s Auschwitz -

The pearl of Africa: Stanley Johnson’s journey into Uganda’s wild heart

The pearl of Africa: Stanley Johnson’s journey into Uganda’s wild heart -

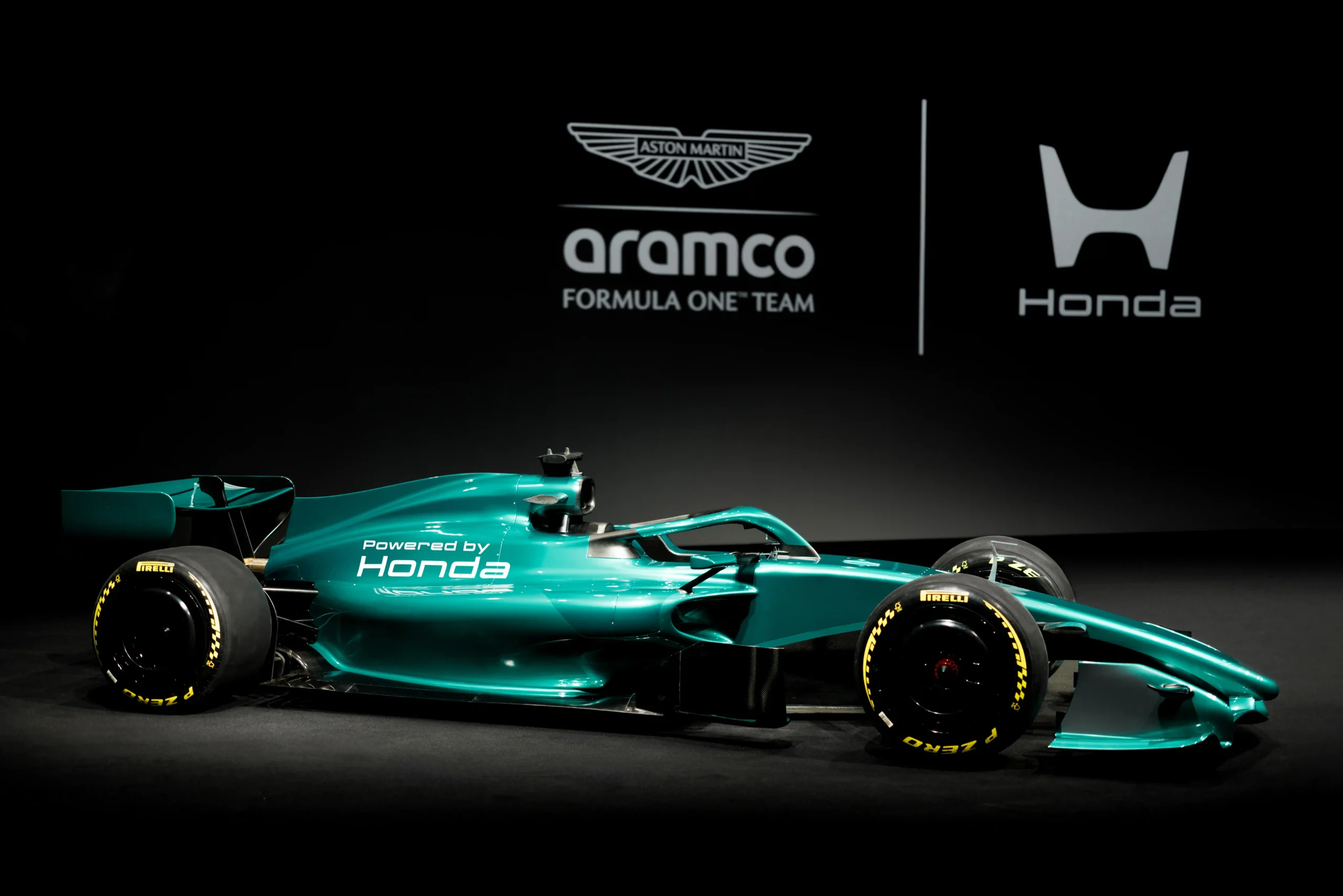

A new green dawn: inside Aston Martin’s turbulent start to Formula 1’s 2026 revolution

A new green dawn: inside Aston Martin’s turbulent start to Formula 1’s 2026 revolution -

WPSL targets £16m-plus in global sponsorship drive with five-year SGI partnership

WPSL targets £16m-plus in global sponsorship drive with five-year SGI partnership -

Need some downtime? Head to Nerja for some serious decompression

Need some downtime? Head to Nerja for some serious decompression -

How a book becomes a ‘bestseller' (and it’s not what you think)

How a book becomes a ‘bestseller' (and it’s not what you think) -

Fipronil: the silent killer in our waterways

Fipronil: the silent killer in our waterways -

Addiction remains misunderstood despite clear medical consensus

Addiction remains misunderstood despite clear medical consensus -

New guide to the NC500 calls time on 'tick-box tourism'

New guide to the NC500 calls time on 'tick-box tourism' -

Bon anniversaire, Rétromobile: Paris’ great motor show turns 50

Bon anniversaire, Rétromobile: Paris’ great motor show turns 50 -

Ski hard, rest harder: inside Europe’s new winter-wellness boom

Ski hard, rest harder: inside Europe’s new winter-wellness boom -

Baden-Baden: Europe’s capital of the art of living

Baden-Baden: Europe’s capital of the art of living -

Salzburg in 2026: celebrating 270 years of Mozart’s genius

Salzburg in 2026: celebrating 270 years of Mozart’s genius -

Sea Princess Nika – the ultimate expression of Adriatic elegance on Lošinj

Sea Princess Nika – the ultimate expression of Adriatic elegance on Lošinj -

Hotel Bellevue, Lošinj, Croatia – refined wellness by the Adriatic

Hotel Bellevue, Lošinj, Croatia – refined wellness by the Adriatic -

Padstow beyond Stein is a food lover’s dream

Padstow beyond Stein is a food lover’s dream -

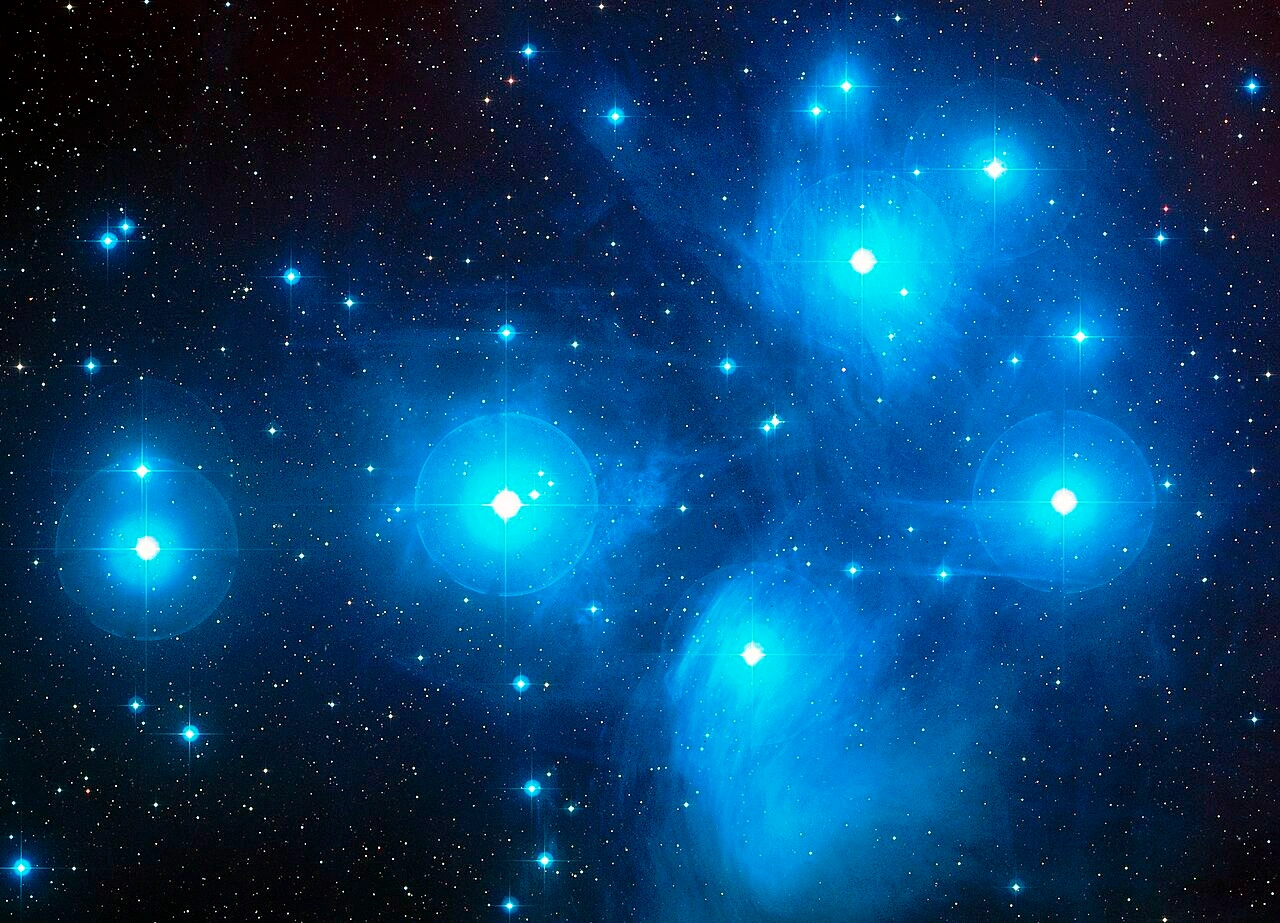

Love really is in the air. How to spot a sky full of heart-stealing stars this Valentine's Day

Love really is in the air. How to spot a sky full of heart-stealing stars this Valentine's Day -

Cora Cora Maldives – freedom, luxury and a celebration of island life

Cora Cora Maldives – freedom, luxury and a celebration of island life -

Hotel Ambasador: the place to stay in Split

Hotel Ambasador: the place to stay in Split -

Maslina Resort, Hvar – mindful luxury in the heart of the Adriatic

Maslina Resort, Hvar – mindful luxury in the heart of the Adriatic -

The bon hiver guide to Paris

The bon hiver guide to Paris -

Villa Mirasol – timeless luxury and discreet elegance on the island of Lošinj

Villa Mirasol – timeless luxury and discreet elegance on the island of Lošinj -

Lošinj’s Captain’s Villa Rouge sets a new standard in private luxury hospitality

Lošinj’s Captain’s Villa Rouge sets a new standard in private luxury hospitality -

Villa Nai 3.3: A Michelin-recognised haven on Dugi Otok

Villa Nai 3.3: A Michelin-recognised haven on Dugi Otok