Don’t panic! It’s time for a Grandad’s Army, historian says

Dr Linda Parker

- Published

- Opinion & Analysis

With British Army numbers at a 200-year low and Gen Z shunning service, it’s time to revive the spirit of Captain Mainwaring and the Home Guard, argues military historian Dr Linda Parker

The regular British Army now has just 73,000 full-time trained personnel, the lowest number since the 18th century.

And the recruitment issue isn’t looking like it’s going to improve any time soon, with only 11 per cent of Gen Z willing to fight for king and country.

The result is an Army that is overstretched, undermanned and under-equipped, and I explored exactly why that is a major problem into today’s world in my last column, Britain is sleepwalking into war — it’s time to wake up.

If we are serious about reversing this crisis, we need to think more radically about the solution.

The answer lies in looking beyond how we recruit to who we recruit.

Currently, the British Army’s upper age limit for new recruits is 35 years and six months for regular soldiers, and 28 years and 11 months for regular officers.

Some specialist roles, such as medical or legal officers, allow applications up to age 55. In the Army Reserve, the part-time volunteer force which currently stands at around 26,000 personnel, the cut-off is 42 years and 11 months for soldiers and 48 years and nine months for officers.

While these limits reflect physical and operational demands, they also exclude a significant number of older men and women who may still have much to offer.

In May 1940, as the threat of Nazi invasion loomed, PM Winston Churchill called on men outside the official age of conscription to form a Local Defence Volunteer force. Open to those younger than 17 and older than 65, this ‘Dad’s Army’, as it was affectionately dubbed, became a symbol of national resolve and, in later decades, something looked on with fond nostalgia (not least, forming the basis of one of Britain’s most cherished sitcoms, Dad’s Army).

But set aside the exploits of Captain Mainwaring and Lance-Corporal Jones for a moment. The Local Defence Volunteer force reflected a simple yet forgotten truth: when the stakes are high enough, the rules change. Everyone counts and everyone, irrespective of age, can still make a valuable contribution.

Today’s security threats are different to those during the Second World War but no less real. With war still raging in Ukraine, NATO commitments increasing, and the UK’s special defence relationship with the U.S more fragile than ever, we may soon be required to act quickly and independently.

And if we can no longer rely on the traditional 18–25 age group to fill the Army ranks then we must by necessity look to the UK’s older population.

This isn’t, of course, for front-line combat. Even the most physically fit people in their late forties and upwards can’t compare to those in their twenties.

But what they can bring is their experience and their expertise. They are ideally placed to fill roles in logistics, cybersecurity, intelligence, training, pastoral care, administration and support — the cogs that keep the military machine running.

I am not alone in raising this idea. In 2023, former Defence Minister Dr Andrew Murrison suggested reviewing rigid military retirement ages, noting there is “no philosophical barrier” to extending service, particularly for roles where experience outweighs physical demands.

If the government were to revise the current recruitment policy, allowing older people to formally enlist for full-time or part-time non-combat roles, perhaps even as far as accepting those in their eighties and nineties if they are fit and well for their age, then it could be a gamechanger for our armed forces.

Such a Grandad’s Army, so to speak — allowing healthy and willing individuals aged 50 and over to serve in support roles — could in principle boost the Army by nearly six million, more than a 7,700 per cent increase over the current total strength.

And if you widen it to the UK Armed Forces in total, which currently stands around 182,000 personnel, then they would grow in numbers by around 3,100 per cent.

Think about it. If upper age limits are removed, and even if only a fraction of those now eligible come forward, Britain’s Army recruitment crisis could be solved in just one day.

While not in the military, there has been a notable increase since the pandemic in the number of retired people re-entering the workforce. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) reports that of the two million who retired during Covid, many are now rejoining the labour force. While 27 per cent cite financial need, a much larger 60 per cent say they simply want something purposeful to do.

What could be more purposeful than serving the nation through its armed forces, especially in its time of need?

Dr. Linda Parker is widely considered to be one of Britain’s leading polar and military historians. She is the author of six acclaimed books, an in-demand public speaker, the co-founder of the British Modern Military History Society, and the editor of Front Line Naval Chaplains’ magazine, Pennant, which examines naval chaplaincy’s historical and contemporary role.

Main image: Courtesy Keith Evans (Creative Commons)

Sign up to The European Newsletter

RECENT ARTICLES

-

Ai&E: the chatbot ‘GP’ has arrived — and it operates outside the law

Ai&E: the chatbot ‘GP’ has arrived — and it operates outside the law -

Keir Starmer, Wes Streeting and the Government’s silence: disabled people are still waiting

Keir Starmer, Wes Streeting and the Government’s silence: disabled people are still waiting -

The fight for Greenland begins…again

The fight for Greenland begins…again -

Failure is how serious careers in 2026 will be shaped

Failure is how serious careers in 2026 will be shaped -

Poland’s ambitious plans to power its economic transformation

Poland’s ambitious plans to power its economic transformation -

Europe’s space ambitions are stuck in political orbit

Europe’s space ambitions are stuck in political orbit -

New Year, same question: will I be able to leave the house today?

New Year, same question: will I be able to leave the house today? -

A New Year wake-up call on water safety

A New Year wake-up call on water safety -

The digital euro is coming — and Europe should be afraid of what comes with it

The digital euro is coming — and Europe should be afraid of what comes with it -

Make boards legally liable for cyber attacks, security chief warns

Make boards legally liable for cyber attacks, security chief warns -

Why Greece’s recovery depends on deeper EU economic integration

Why Greece’s recovery depends on deeper EU economic integration -

Why social media bans won’t save our kids

Why social media bans won’t save our kids -

This one digital glitch is pushing disabled people to breaking point

This one digital glitch is pushing disabled people to breaking point -

Japan’s heavy metal-loving Prime Minister is redefining what power looks like

Japan’s heavy metal-loving Prime Minister is redefining what power looks like -

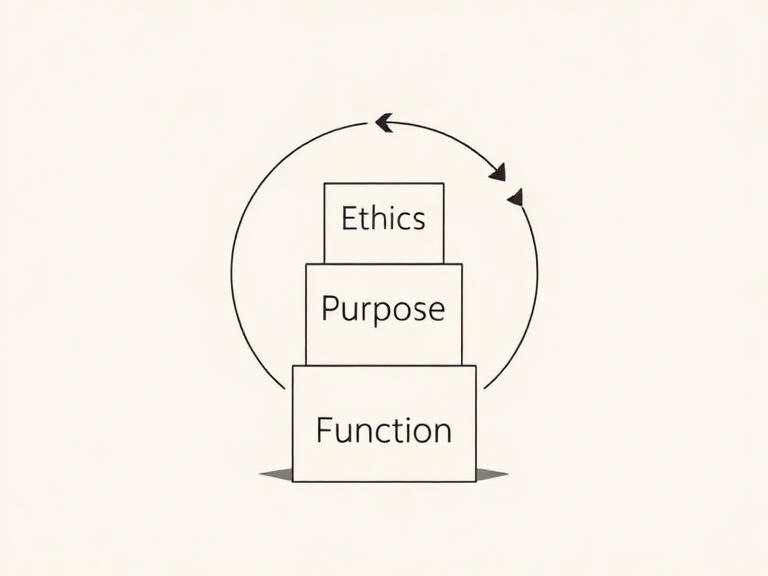

Why every system fails without a moral baseline

Why every system fails without a moral baseline -

The many lives of Professor Michael Atar

The many lives of Professor Michael Atar -

Britain is finally having its nuclear moment - and it’s about time

Britain is finally having its nuclear moment - and it’s about time -

Forget ‘quality time’ — this is what children will actually remember

Forget ‘quality time’ — this is what children will actually remember -

Shelf-made men: why publishing still favours the well-connected

Shelf-made men: why publishing still favours the well-connected -

European investors with $4tn AUM set their sights on disrupting America’s tech dominance

European investors with $4tn AUM set their sights on disrupting America’s tech dominance -

Rachel Reeves’ budget was sold as 'fair' — but disabled people will pay the price

Rachel Reeves’ budget was sold as 'fair' — but disabled people will pay the price -

Billionaires are seizing control of human lifespan...and no one is regulating them

Billionaires are seizing control of human lifespan...and no one is regulating them -

Africa’s overlooked advantage — and the funding gap that’s holding it back

Africa’s overlooked advantage — and the funding gap that’s holding it back -

Will the EU’s new policy slow down the flow of cheap Chinese parcels?

Will the EU’s new policy slow down the flow of cheap Chinese parcels? -

Why trust in everyday organisations is collapsing — and what can fix it

Why trust in everyday organisations is collapsing — and what can fix it