Netflix’s Adolescence has exposed a society that still doesn’t believe women

Dr Raj Joshi

- Published

- Opinion & Analysis

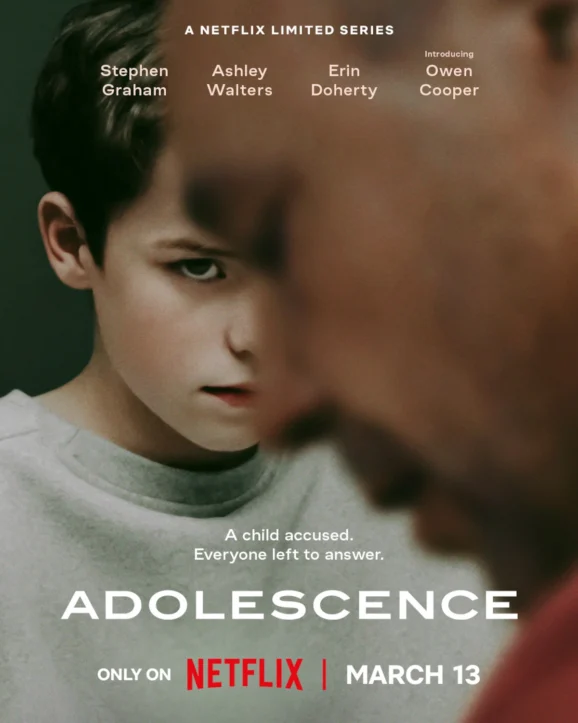

Netflix’s Adolescence has been praised for its disturbing portrayal of how teenage boys are pulled into violent misogynistic ideologies. But, warns barrister and former chair of the Society of Black Lawyers, Raj Joshi, the greater danger lies off screen — in the failure of the UK’s legal, educational and political systems to recognise misogyny as a hate crime, deliver justice to victims, or confront the cultural forces fuelling violence against women

There’s nothing explosive about the way Adolescence opens. No graphic violence. No heavy moralising. Just a boy, a family, a quiet community, and the slow reveal that something is deeply wrong.

If you haven’t seen it, Netflix’s chilling new drama centres on 13-year-old Jamie Miller, who is arrested for the murder of a classmate. Over four episodes, the story peels back the layers: the bullying, the social media messages, the unspoken expectations around masculinity. His parents are left guessing. His teachers are defensive. The men around him either don’t see the signs or see them and look away.

What Adolescence captures, with quiet precision, is the way misogyny, digital radicalisation and emotional repression can shape a boy long before anyone realises the damage. There’s no single moment when Jamie changes. It happens gradually, in between therapy sessions, group chats and glances across the dinner table. The show isn’t telling a horror story. It’s showing how ordinary life can bend toward something much darker when nobody intervenes. Unfortunately, the story focuses on the perpetrator rather than the female victim, with the narrative driven by the men involved. Female characters are peripheral, aside from a female psychiatrist, who serves mainly to advance the reveal of the adolescent’s ‘real’ character.

The characters are fictional. The conditions are not. Across the UK, these pressures are already shaping how boys behave – and how girls are forced to respond. Misogyny has become part of the background noise in schools, on phones, in bedrooms. And when violence erupts, everyone acts surprised. But surprise is no longer an excuse.

In Adolescence, Jamie’s worldview is shaped by what he consumes online – a steady drip-feed of grievance, entitlement, and distorted ideas about gender. The language he starts using, and the beliefs he adopts, come from a digital subculture where boys are told that women are to blame for their pain. This is where he finds validation. And he’s far from alone.

That culture has a name: incel. The term – short for “involuntary celibate” – was coined in the 1990s by a Canadian woman, Alana, who wanted to create a supportive community for people struggling with intimacy and isolation. Her project was inclusive and non-gendered.

Over time, the word was appropriated by men who recast their social frustration as victimhood and directed their anger toward women.

Today, incel forums encourage violence and reward hatred. They describe women as manipulative obstacles and celebrate those who act on their rage. The forums offer a distorted worldview that now reaches far beyond fringe internet communities. These same forums, claiming men are hard done by, also perpetuate chauvinism and bigotry, ignoring the reality that men remain the dominant group in society. The pernicious “lad culture” of the 1990s has evolved into insidious online trolling and coordinated campaigns seeking to reassert a male dominance that has never truly been lost.

It is convenient to cling to the idea of a male epidemic of loneliness and isolation. However, the incel forums, where thousands if not millions of men and boys congregate, show that these individuals are not isolated. They are socialising actively online. Toxic masculinity, rape culture and misogyny are not things that happen to men. But even when women and girls are raped, sexually assaulted, harassed or subjected to violence, with lifelong PTSD as a result of male action, the narrative still centres on males being misunderstood or emotionally repressed. Recently, Telegram group chats involving over 70,000 men shared information and explicit videos on immobilising, assaulting and raping women, including sisters, mothers and friends.

Andrew Tate, a prominent online figure, has described women as “barely sentient” and “empty vessels”. His content is consumed by millions. Teachers across the UK report that boys are repeating his phrases in school, often without understanding the weight of what they’re saying. The gap between online rhetoric and offline behaviour is narrowing.

Social media platforms act swiftly to remove other forms of extremist material. Yet misogynistic content, even when it incites harm, remains readily accessible. There is no coherent strategy to deal with this — and the consequences are becoming harder to ignore.

Legal Indifference Isn’t Neutral

When campaigners urged the UK government to recognise misogyny as a hate crime, the Home Office refused. Ministers argued that existing laws were enough — that crimes motivated by misogyny could already be prosecuted under general hate crime or public order offences.

But that’s not how it plays out in practice. Without specific recognition in law, misogyny is not recorded, monitored, or tracked in any meaningful way. There is no legal obligation to treat it as an aggravating factor. Most of the time, it disappears from the record.

Scotland has taken a different approach. Following a public consultation and the work of an independent review led by Baroness Helena Kennedy KC, the Scottish Government committed to new legislation that explicitly criminalises misogynistic abuse. That includes offences based on threatening or abusive behaviour directed at women because of their gender. The aim is as much about prosecution as it is prevention, and it sends a clear statement that misogyny is being taken seriously at the level of law.

No such step has been taken in England or Wales. Here, women still face a legal system that often feels – and most likely is – indifferent. Investigations into violence or abuse are frequently delayed. Victims are made to wait months, sometimes years, for any progress. Evidence is lost or mishandled. Communication breaks down. Serious charges collapse before they ever reach court. Even when cases proceed, survivors are put through a process that is traumatising in itself.

For many, the decision to report a crime is a gamble — one that rarely pays off. And without clear legal recognition of misogyny as a motivating force, the system continues to treat it as background noise rather than a defining feature of the harm women face.

For Black and mixed-ethnicity women, these failures are even more pronounced. They experience higher rates of sexual violence and lower rates of support. In 2022, the Home Affairs Committee began investigating how rape is prosecuted in England and Wales. As part of that inquiry, the Criminal Bar Association submitted oral evidence. Despite the scale of the problem, the submission made no reference to the disproportionate impact of sexual violence on Black, mixed-ethnicity and other minoritised women. Women of South-Asian heritage experience domestic abuse at roughly half the rate reported by their white counterparts, yet the problem is acknowledged to be greater due to the failures of police responses. Although underreporting of sexual abuse and violence is widely recognised, the issue is often dismissed as stereotypical of ‘culture’, ignoring the very real bias and prejudice that South Asian victims face.

This omission is not trivial. There is longstanding evidence that women from these communities are more likely to experience sexual assault and less likely to receive support from the justice system. Failing to acknowledge this by the most powerful organisation of criminal barristers in such a high-level review reflects the limited appetite within legal institutions to address inequality head-on. It shows that race is still treated as peripheral, even in discussions about one of the most serious failings of the criminal justice system.

A recent case illustrates the depth of the problem. A woman was assaulted on the London Underground. She was punched in the face by a stranger. She pressed the emergency alarm and had no response. She got off the train and used the help points but still nothing. She phoned 999 and waited.

Nobody arrived for over 30 minutes.

This didn’t happen on a deserted platform or in the middle of the night. It happened on one of the world’s busiest transport networks.

The woman’s experience reflects a broader failure. According to the National Audit Office, police-recorded rape and sexual assault cases increased from 34,000 to more than 123,000 in the space of a year. More than one million offences linked to violence against women and girls (VAWG) were recorded in 2022–23. The vast majority of domestic abuse victims are women. One in four women in the UK will experience sexual assault or an attempted assault during her lifetime. And fewer than 3% of rape reports result in a charge within the same year.

These delays and failures are not the result of occasional mistakes. Rather, they point to deeper problems across the justice system. Cases involving violence against women are often treated without urgency. Investigations stall, communication breaks down, and too many victims are left navigating the process alone. Many are not believed. Many give up.

In other types of crime including robbery, burglary, and physical assault, there is an assumption of truth, followed by an investigation. With sexual violence, that starting point often shifts. Belief is conditional and justice uncertain.

The UN defines violence against women as any act of gender-based harm that causes, or is likely to cause, physical, sexual or psychological suffering. This includes coercion, threats, and deprivation of liberty. The definition is straightforward. The legal framework should be too.

Yet when it comes to implementation, the UK government still lacks coordination and resolve. In a recent report, the National Audit Office stated:

“The Home Office is not currently leading an effective cross-government response. It has a limited understanding of the extent of resources devoted to addressing VAWG… Without this knowledge, the government cannot be confident that it is doing the best it can to keep women and girls safe.”

Meanwhile, social media continues to host misogynistic content with no clear accountability. Classrooms reflect a growing disrespect for women. Victims are still blamed more often than supported. Public trust in the justice system is eroding.

What Needs to Change

Let us be clear: the UK is not dealing with misogyny in any meaningful way. It is not being treated as a priority in law, education, policing, or national policy. That needs to change.

Misogyny should be recognised as a hate crime in England and Wales. Scotland has introduced this, despite opposition. The rest of the UK has no such legal definition. Without it, there is no proper mechanism for tracking or prosecuting gender-based hatred. There is also no deterrent. This legal gap gives abusers confidence and leaves victims unprotected.

The criminal justice system also needs to function. That means police officers must be trained properly, victims must be supported throughout the process, and courts must have the resources to act quickly. Serious cases cannot take years to reach trial. Delays and inconsistency are part of what drives people away from reporting in the first place.

Schools need a national plan for education around misogyny, consent, and online abuse. Teachers are already dealing with a rise in sexist behaviour among pupils. Without proper resources and direction, schools cannot respond effectively. Education must start early and must be compulsory.

Social media platforms must face consequences for hosting and promoting misogynistic content. The incel ideology is being spread widely online with little resistance. The same platforms that act on some forms of extremism are ignoring violence against women. That inconsistency is part of the problem. The government must make regulation enforceable and clear.

There is no joined-up national strategy. The Home Office does not know how much money or staff are being directed at violence against women. No department is in charge of setting standards or measuring outcomes. A coordinated national response is the minimum that should be in place. At the moment, it does not exist.

Adolescence may be fiction, but the world it portrays is not. The conditions that shaped Jamie are already shaping boys across the UK and should be dealt with the way that other forms of radicalisation are dealt with and using the same tools. Without serious reform, more families will face the same aftermath, and more women and girls will be left unprotected.

More than anything else, men and boys need to change.

Raj Joshi is a senior barrister and former chair of the Society of Black Lawyers. He was named among the Top 10 Asian Lawyers in the UK and the 100 Most Influential Asians in the UK. He has advised the Judicial Studies Board, and served as an adjudicator, campaigner, and legal advisor across multiple institutions tackling race, justice, and equality.

Photos: Netflix

RECENT ARTICLES

-

The era of easy markets is ending — here are the risks investors can no longer ignore

The era of easy markets is ending — here are the risks investors can no longer ignore -

Is testosterone the new performance hack for executives?

Is testosterone the new performance hack for executives? -

Can we regulate reality? AI, sovereignty and the battle over what counts as real

Can we regulate reality? AI, sovereignty and the battle over what counts as real -

NATO gears up for conflict as transatlantic strains grow

NATO gears up for conflict as transatlantic strains grow -

Facial recognition is leaving the US border — and we should be concerned

Facial recognition is leaving the US border — and we should be concerned -

Wheelchair design is stuck in the past — and disabled people are paying the price

Wheelchair design is stuck in the past — and disabled people are paying the price -

Why Europe still needs America

Why Europe still needs America -

Why Europe’s finance apps must start borrowing from each other’s playbooks

Why Europe’s finance apps must start borrowing from each other’s playbooks -

Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes

Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes -

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others -

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again -

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart?

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart? -

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing -

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage -

The limits of good intentions in public policy

The limits of good intentions in public policy -

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament?

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament? -

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth -

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours -

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality -

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now -

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day -

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy -

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it -

What if he falls?

What if he falls? -

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world