Want a job in the video games industry? Here’s the ultimate employment cheat code

Aleksey Savchenko

- Published

- Opinion & Analysis

Forget modern university degrees. If you really want a job in today’s gaming industry, you need to go old-school, writes veteran developer Aleksey Savchenko

For many young people, landing a job in the video game industry is the ultimate in cool. Who wouldn’t want to help create the next adventures for Mario, Sonic, Master Chief and a whole host of other iconic characters?

But ask any school-leaver how to get a job and the answer is usually the same: get a degree. It’s been drilled into them by universities, careers advisers, and glossy marketing materials as the be-all and end-all route to success.

After decades in the video game business, here’s the truth I wish more people were told from the start: you don’t need a degree.

Sure, universities team up with studios to funnel graduates into jobs but it’s not the only way in, and it’s not even the best way given how poorly some degree courses do in prepping students for the real-world demands of the job.

In some cases, a degree is a complete waste of time. Who honestly cares that you have learned the theory of storytelling or the finer points of artistic vision. If you really want to work in games, then prove it. Actually make games. Right now. On your laptop in your bedroom That will teach you far more, far faster, than most university courses ever could. It’s no different to becoming an engineer by pulling apart engines in a garage or a builder by picking up tools and laying bricks. You don’t become a chef by reading menus – you get into the kitchen and cook.

Studios are impressed by those who do, not say. They want people who can build more than those who have just sat through lectures thinking about building. If you can demonstrate that you understand the development process by showing something you’ve actually made then you’re already halfway to getting your foot in the door.

And you don’t need permission or a huge bank balance to start. Download a game engine – Unreal or Unity, for example – and open up a few sample projects. They’re free for individuals and you only need to pay for a licence when you start hitting big sales, measured in hundreds of thousands of pounds.

Tinker. Break things. Fix them. Try to recreate your favourite game mechanic. Then try to improve it. You’ll learn through doing, from your mistakes as much as your triumphs, and as you go, you’ll discover where your strengths lie. It might be in programming, animation, technical art, audio or something else entirely.

This kind of practical, self-driven learning does more than just teach you how games work. It helps you build a portfolio. Even small, simple projects show that you can finish something, that you’ve grappled with real development challenges, and that you’re serious. That’s what makes people take notice.

Better still, working on your own projects gives you creative control. You’re not just learning, you’re discovering what you actually want to do. And when you share your work, you’ll likely find others who want to collaborate. That’s how teams form, and how studios and careers begin – not in classrooms, but through shared effort and working prototypes.

This is not to say that a degree is entirely worthless. Some can be helpful, particularly in areas like computer science or 3D art. But if you don’t know exactly what skills you want to build, you risk spending years and thousands of pounds on something that leaves you no better equipped for the games industry than if you’d just watched a few documentaries on Super Mario.

Working from your bedroom might not seem as prestigious to outsiders as getting into to one of the top courses at one of the top universities, but it’s the messy, practical work – the assembly of games – that’s the real qualification.

And while the industry is shifting rapidly thanks to AI, that only makes hands-on skills more important. Tools are becoming smarter, but they still need creative, technically-minded people to direct them. Again, universities mainly do lip service to AI in gaming. Without that real-world, hard-earned grounding, if you do get funnelled into a job then you risk becoming a button-pusher rather than a creator – easily replaced and quickly forgotten.

Once you’ve made a few things on your own, you’ll be in a much stronger position to make decisions about your next steps. Maybe you decide to apply directly to studios, armed with playable demos. Maybe you build a team and continue independently. Or maybe you choose to study further but with the benefit of a clear focus and a better idea of what you need to learn.

In any case, the hard part – actually getting started – is already behind you.

It’s not spoken loudly but many of today’s top developers began their careers in their bedrooms, and that’s how new indie studios are still being born every day.

So if you really want to break into the industry, start now. Build something small and share it. And if someone ever asks what qualifications you have, point them to your work. Because that’s what really matters.

Aleksey Savchenko is a veteran game developer, futurist, author, and BAFTA member with nearly three decades’ expertise in the tech and entertainment industries. Currently the Director of RnD, Technology and External Resources at GSC Game World, he has worked on the studio’s acclaimed S.T.A.L.K.E.R. 2. He has also worked for Epic Games, known for Fortnite and its technical achievements in middleware technologies worldwide, playing an instrumental role in establishing an Unreal Engine with Eastern European developers. He is the author of Game as Business and the Cyberside series of cyberpunk graphic novels.

Main image, courtesy Aleksey Savchenko/Palamedes

RECENT ARTICLES

-

The era of easy markets is ending — here are the risks investors can no longer ignore

The era of easy markets is ending — here are the risks investors can no longer ignore -

Is testosterone the new performance hack for executives?

Is testosterone the new performance hack for executives? -

Can we regulate reality? AI, sovereignty and the battle over what counts as real

Can we regulate reality? AI, sovereignty and the battle over what counts as real -

NATO gears up for conflict as transatlantic strains grow

NATO gears up for conflict as transatlantic strains grow -

Facial recognition is leaving the US border — and we should be concerned

Facial recognition is leaving the US border — and we should be concerned -

Wheelchair design is stuck in the past — and disabled people are paying the price

Wheelchair design is stuck in the past — and disabled people are paying the price -

Why Europe still needs America

Why Europe still needs America -

Why Europe’s finance apps must start borrowing from each other’s playbooks

Why Europe’s finance apps must start borrowing from each other’s playbooks -

Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes

Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes -

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others -

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again -

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart?

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart? -

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing -

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage -

The limits of good intentions in public policy

The limits of good intentions in public policy -

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament?

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament? -

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth -

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours -

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality -

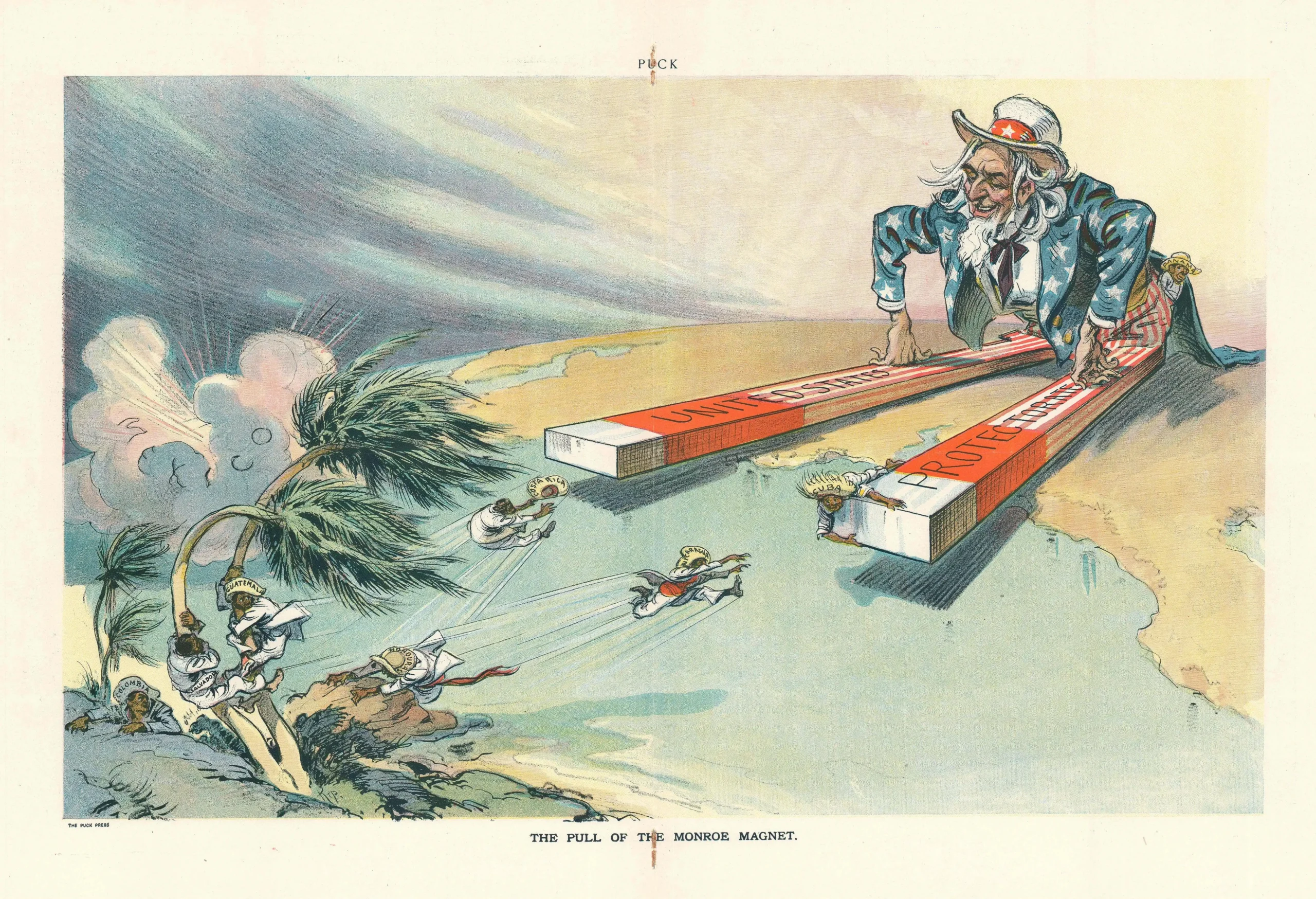

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now -

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day -

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy -

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it -

What if he falls?

What if he falls? -

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world