Book Review: A history of the world told by animals — and it changes everything

John E. Kaye

- Published

- Lifestyle

What if every creature that ever lived carried a memory of the world, and Earth’s history stretched far beyond the human record? Will Shin’s Animal Intelligence invites readers into a universe where whales negotiate, cats critique civilisation and extinct species finally tell their side of the story — and the result is a surprisingly elegant argument for seeing the planet anew

“Only nature knows neither memory nor history. But man – let me offer you a definition – is the storytelling animal”, wrote Graham Swift in Waterland. His oft-quoted line suggests that what sets mankind apart is the impulse to turn memory into story and story into history — a uniquely human way of making sense of the world.

Swift is right in the narrow, human sense. History only exists when someone writes it down or tells it aloud. Animals evolve, migrate, fight, hide, nurture, adapt and form alliances across millions of years, yet none of that appears in the historical record for the obvious reason: they have no spoken archive. They might have been comparing notes among themselves for ages — perhaps they still do — but humans have never been able to understand, record or translate whatever has passed between them.

Will Shin, an accomplished scholar and academic, responds with an irresistible thought experiment: what if Earth has always contained more storytellers than we realised?

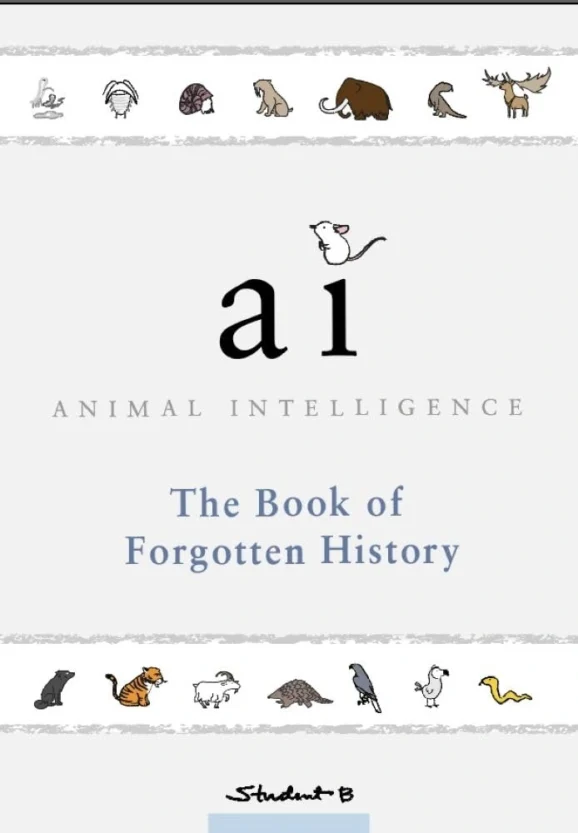

Animal Intelligence: The Book of Forgotten History, his beguiling work of illustrated fiction and the first volume of a planned trilogy, imagines that every animal that ever lived carries a memory of the world. These memories stretch from the first oceans to a distant post-human age and create a vast, informal record of how life unfolded long before humans began chiselling marks into stone. Shin proposes that animals observed everything — the leaps, the failures, the quiet triumphs, the collapses — and now offer their version of the story we thought we understood.

“The history written from the memory of wild animals is never precise,” he notes in the preamble. “Readers raised on human history may find these events tangled and flawed…But that doesn’t make these records meaningless.”

This premise becomes the foundation for a philosophical yet accessible hybrid work that reimagines human history — and the future of knowledge — through the eyes of animals. Designed for both adults and younger readers, it uses narrative, gentle illustration and fable to explore large ideas without heaviness. More than a standalone book, it opens the Animal Intelligence series: a long-term knowledge project that approaches long-termism and post-human thought from non-human perspectives. Future volumes will extend this framework to examine how animals interpret human knowledge, technology and institutions, offering an alternative way of thinking about intelligence, memory and the world to come.

The narrative moves across ten eras of Earth’s past — the book calls them epochs — beginning with the Paleozoic’s “Age of Arrogance” and its star, Spriggina, a smug organism with more self-belief than body mass. The Mesozoic becomes the “Age of Wars”, where dinosaurs pursue strategies that work until they very much do not. The Cenozoic “Age of Myths” sees early humans forging alliances with animals that unravel for reasons neither side fully grasps. Medieval Europe becomes the “Age of Mirrors”, witnessed by cats with sharp opinions and rats with even sharper ones. Later chapters follow animals carried across seas during exploration, animals watching industrial modernity with a sinking feeling, and animals in the contemporary world adopting new vantage points as quiet observers. The final “Age of Remembrance”, set in a far future, wonders how the planet might remember us once humanity has stepped aside.

Throughout, animals speak with plain, unfussy and, dare I say it, believable voices. Whales attempt diplomacy with humans. Horses and hawks survey empires like creatures who have sat through one cavalry campaign too many. Cows cross the Atlantic with stoic acceptance. Their memories describe how intelligence evolves, loses its footing, tries again and occasionally takes decisions that are imaginative at best and ill-advised at worst.

The book blends fable, natural history, comic-style illustration and gentle philosophy with a mischievous sense of humour, and its illustrations — created by Alice Shin, the author’s sister — give the story much of its warmth. Her drawings carry expression, timing and small jokes that guide readers through vast stretches of time without losing them. Panels soften large ideas, allow jokes to land, and help readers intuit emotional changes in the story. They support the narrative with the lightness needed for younger readers while offering adults enough detail to linger on.

Together, the sibling pair form a formidable creative duo. Will studied Artificial Intelligence at the University of Pennsylvania and International Development at Harvard, and his background shapes the structure and ambition of the animal-centred universe he is building. Alice’s training in art and linguistics gives the illustrations their clarity, movement and quiet humour. Their publishing imprint, STUDENT B, brings these approaches together into a coherent long-term project.

The Animal Intelligence series unfolds from this foundation. This first volume lays the historical and conceptual groundwork, concentrating on memory, perspective and the long relationships between species. Subsequent volumes follow as direct sequels, turning to the present to explore how animals live today, how they study and evaluate human knowledge, and how these assessments shape their views of the future. Animals emerge as long-term observers who have watched human civilisation from the edges and now choose to speak.

A broad readership can move through this book with ease. Adults who enjoy natural history, world-building or philosophical storytelling will find depth without difficulty. Teen readers who like illustrated or myth-shaped worlds will fall into its rhythm quickly. Families can read it together across ages, and younger readers absorb the emotional content carried by the animals even when the larger ideas run beneath the surface. Educators, museums, wildlife centres and STEAM programmes, meanwhile, will gain a simple way to introduce ideas about evolution, knowledge, environmental philosophy and long-term thinking. The book, out this week, reads as though animals have been watching us with patient amusement for far longer than we suspected — and have decided it might be time, very politely, to set the record straight.

Q&A with author Will Shin

Will Shin reflects on the inspiration, structure and ambition behind Animal Intelligence, and outlines how the trilogy will explore intelligence, memory and the future through animal perspectives

The European: What first inspired you to write Animal Intelligence: The Book of Forgotten History?

Will Shin: I wanted to reimagine human history and modern knowledge as a single, unified story, and telling it through the eyes of animals felt like the most honest — and engaging — way to begin. Many readers form emotional connections with animals long before they engage with philosophy or science, so that perspective opens the door to a wider audience.

I’ve raised several animals in my life, and there are moments when you meet their eyes and sense a presence looking back. It isn’t speculation about what they think; it feels like an encounter between two beings. Those moments became the seed of the idea — the sense that every creature carries a perspective, a memory and a way of seeing the world that humans rarely acknowledge.

The book is part history, part fable, and part philosophy. How did this hybrid form develop?

My academic background spans artificial intelligence and social science, and I wanted to bring those strands together in a form that stayed imaginative enough to welcome younger readers while still carrying deeper ideas for adults.

At first, I tried writing in more traditional forms, closer to textbooks or essays, but I realised that the ideas would remain abstract unless they were placed in a world readers could care about. That is how the hybrid form emerged. My sister Alice and I chose animals — a universal point of connection — and began experimenting with comic-style storytelling as a way to introduce philosophical themes lightly. The result is still evolving as the series grows.

Why tell evolution and history from the perspective of animals rather than humans?

Animals carry a kind of time that humans often forget. Their memories — including imagined memories of extinct species — reveal history as a long continuum rather than a series of human milestones.

With an animal viewpoint, the story becomes less about human progress and more about how intelligence changes. It becomes a study of how life adapts, remembers, hopes, fears and survives. That shift opens discussions about extinction, knowledge and responsibility in a way that is intuitive even for younger readers.

The narrative introduces post-human thinking and long-term stewardship. How do you make these ideas accessible for parents and young readers?

In later volumes, ideas of long-termism become clearer. Animals introduced in this book return to a world unsettled by humans, offering ways of thinking about how that world might be repaired. At the same time, the animals themselves act as a simple metaphor: intelligent beings who help humanity survive, suggesting a post-human way of thinking about intelligence and responsibility.

The book was originally written for adults, but we soon realised that metaphor and character help these ideas come across more gently. This shaped the current version, which we now see as something families can read together: adults recognise the philosophical ideas, while younger readers follow the emotional journeys of the animals.

What do you hope children — and the adults reading with them — take away from this book?

That the memories and knowledge of many lives matter. If we gather the experiences of all creatures — including those that no longer exist — new possibilities for the future become visible. History is not fixed, intelligence is not singular, and the future is something we shape through attention, imagination and empathy.

The artwork is by Alice Shin. How did your creative partnership work, and what do the illustrations contribute?

Alice is my sister, and although our professional paths were very different, building this universe together has been one of the great surprises of our lives. Many of the characters in the book are ones we had been carrying in our imaginations for years, long before we ever thought of turning them into a project.

We discuss everything — structure, tone, the emotion behind each panel — and every decision is shared. Her artwork adds clarity, humour and warmth, and it helps younger readers move through very large spans of time without difficulty.

How does the visual style support the storytelling? Does the art extend meaning beyond imagery?

Because the project engages with serious philosophical ideas in an indirect, metaphorical way, illustration is given a deliberate role in lightening their weight. We wanted what might otherwise feel heavy on the page to become more accessible, through an emphasis on character-driven visuals and small jokes.

In the book, extinction becomes a form of memory rather than absence. How do you want families to approach that idea?

I hope readers rethink extinction as more than something that simply ends. Each species leaves behind lessons about survival and change. As the series continues, those lessons come together, imagining animals pooling their wisdom to think about what kind of future might still be possible.

Which species or era in the book are you most connected to emotionally, and why?

Some chapters were written with animals I personally cared for in mind. Chapter 9, in particular, comes from thinking about my own dog. That chapter reflects on the idea that humans are a species defined by memory and record-keeping, and that intelligence includes holding difficult stories and passing them on.

This is the first volume in a wider project. What comes next?

Volumes 2 and 3 move beyond history to examine the body of modern knowledge humans have accumulated, imagining how animals study and evaluate that knowledge as they work to reshape the future of the Earth. These books blend speculative imagination with elements of a textbook, extending the series from historical narrative into learning and reflection.

Between the main volumes, a more comic-driven guidebook will also be released in the January. Set in the present day, it follows animals that appeared throughout history and imagines what they are doing now. Designed to be more family-friendly in format, it still carries the philosophical backbone of the Animal Intelligence series.

READ MORE: ‘Book review: The BBC’s Last Warrior-Statesman by Stephen R.W. Francis‘. The first memoir of Sir Richard Francis is both an intimate portrait of a pioneering champion of public broadcasting and a snapshot on the BBC at the height of its power, finds John E. Kaye.

Do you have news to share or expertise to contribute? The European welcomes insights from business leaders and sector specialists. Get in touch with our editorial team to find out more.

Main image: Jan Koetsier/Pexels

RECENT ARTICLES

-

The European Reads: Kalman & Leopold: Surviving Mengele’s Auschwitz

The European Reads: Kalman & Leopold: Surviving Mengele’s Auschwitz -

The pearl of Africa: Stanley Johnson’s journey into Uganda’s wild heart

The pearl of Africa: Stanley Johnson’s journey into Uganda’s wild heart -

A new green dawn: inside Aston Martin’s turbulent start to Formula 1’s 2026 revolution

A new green dawn: inside Aston Martin’s turbulent start to Formula 1’s 2026 revolution -

WPSL targets £16m-plus in global sponsorship drive with five-year SGI partnership

WPSL targets £16m-plus in global sponsorship drive with five-year SGI partnership -

Need some downtime? Head to Nerja for some serious decompression

Need some downtime? Head to Nerja for some serious decompression -

How a book becomes a ‘bestseller' (and it’s not what you think)

How a book becomes a ‘bestseller' (and it’s not what you think) -

Fipronil: the silent killer in our waterways

Fipronil: the silent killer in our waterways -

Addiction remains misunderstood despite clear medical consensus

Addiction remains misunderstood despite clear medical consensus -

New guide to the NC500 calls time on 'tick-box tourism'

New guide to the NC500 calls time on 'tick-box tourism' -

Bon anniversaire, Rétromobile: Paris’ great motor show turns 50

Bon anniversaire, Rétromobile: Paris’ great motor show turns 50 -

Ski hard, rest harder: inside Europe’s new winter-wellness boom

Ski hard, rest harder: inside Europe’s new winter-wellness boom -

Baden-Baden: Europe’s capital of the art of living

Baden-Baden: Europe’s capital of the art of living -

Salzburg in 2026: celebrating 270 years of Mozart’s genius

Salzburg in 2026: celebrating 270 years of Mozart’s genius -

Sea Princess Nika – the ultimate expression of Adriatic elegance on Lošinj

Sea Princess Nika – the ultimate expression of Adriatic elegance on Lošinj -

Hotel Bellevue, Lošinj, Croatia – refined wellness by the Adriatic

Hotel Bellevue, Lošinj, Croatia – refined wellness by the Adriatic -

Padstow beyond Stein is a food lover’s dream

Padstow beyond Stein is a food lover’s dream -

Love really is in the air. How to spot a sky full of heart-stealing stars this Valentine's Day

Love really is in the air. How to spot a sky full of heart-stealing stars this Valentine's Day -

Cora Cora Maldives – freedom, luxury and a celebration of island life

Cora Cora Maldives – freedom, luxury and a celebration of island life -

Hotel Ambasador: the place to stay in Split

Hotel Ambasador: the place to stay in Split -

Maslina Resort, Hvar – mindful luxury in the heart of the Adriatic

Maslina Resort, Hvar – mindful luxury in the heart of the Adriatic -

The bon hiver guide to Paris

The bon hiver guide to Paris -

Villa Mirasol – timeless luxury and discreet elegance on the island of Lošinj

Villa Mirasol – timeless luxury and discreet elegance on the island of Lošinj -

Lošinj’s Captain’s Villa Rouge sets a new standard in private luxury hospitality

Lošinj’s Captain’s Villa Rouge sets a new standard in private luxury hospitality -

Villa Nai 3.3: A Michelin-recognised haven on Dugi Otok

Villa Nai 3.3: A Michelin-recognised haven on Dugi Otok -

The European road test: The Jeep Wrangler Rubicon

The European road test: The Jeep Wrangler Rubicon