Spot the Big Dipper — and unlock the secrets of the spring sky

Omara Williams

- Published

- Opinion & Analysis

In the second of her stargazing series for The European, keen amateur astronomer and bestselling author Omara Williams explains how the Big Dipper can help you explore the spring night sky — from the Great Bear to the Spring Triangle

Step outside on a clear night this spring and face the southern sky. Look overhead and you’ll see one of the most familiar shapes in the heavens: the Big Dipper.

It’s not a constellation but an asterism — a recognisable pattern of stars. Like Orion’s Belt in winter, it’s your starting point for finding others. Spot it, and you’re on track to find half the night sky.

The Big Dipper looks like a giant saucepan. The bowl is made from four stars, and the handle curves out to the left with three more. It’s always above the horizon in the northern hemisphere but sits especially high in the sky during spring. Even in towns, the brighter stars are usually visible. Once you’ve found it, you can use it to track down five major spring constellations — starting with the one it’s part of.

Find Ursa Major – The Great Bear

The Big Dipper is part of Ursa Major, the Great Bear. The bowl forms the bear’s back; the handle is its tail. The rest of the constellation — its head and legs — is made of fainter stars that stretch off to the side and below.

Different cultures have seen different shapes here: a plough in Britain, a wagon in parts of Europe. But in both Native American and Ancient Greek traditions, this pattern forms a bear. In Greek mythology, the bear refers to Callisto, a nymph turned into a bear and placed among the stars by the jealous goddess Hera.

To move on to the next constellation, use the Big Dipper’s bowl to find the North Star (Polaris) and Ursa Minor.

Find Polaris and Ursa Minor

Look at the two stars on the right side of the Dipper’s bowl: Dubhe at the top and Merak at the bottom. Stretch your arm straight out and use your fingers to measure the gap between them — it’s about two fingers wide. Now draw an imaginary line upward through those stars and extend it about five times that distance. You’ll land on Polaris, the North Star.

Polaris is a yellow supergiant that is nearly five times more massive than our Sun and situated more than 400 light-years away. Though not the brightest, it almost perfectly marks true north and has guided explorers and navigators for centuries.

Polaris sits at the tip of the tail of Ursa Minor, the Little Bear. Like Ursa Major, it forms a saucepan shape, but smaller and fainter. Once you find Polaris, try tracing the curve of stars away from it to spot the bowl and short handle.

Find Arcturus and Boötes

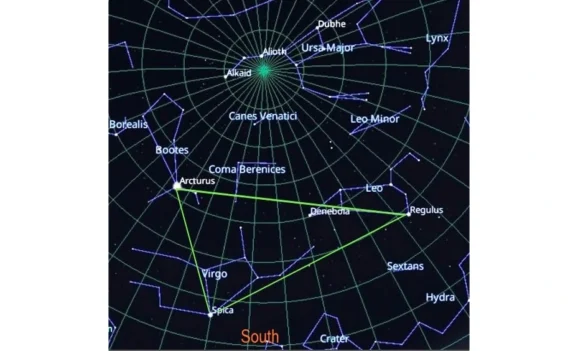

Now return to the Big Dipper’s handle and trace its arc down and to the southeast, like following the swing of a gate. About a clenched fist’s length away, you’ll reach Arcturus, an orange-hued star and the brightest in the spring sky.

Arcturus is a red giant around 40 light-years from Earth. It sits at the base of Boötes, or the Herdsman — a kite-shaped constellation of eight to ten visible stars. The name Arcturus means “Guardian of the Bear”, as it shines near both Ursa Major and Ursa Minor.

Keep tracing the same gentle arc from the Dipper’s handle, past Arcturus, and you’ll arrive at Spica.

Find Spica and Virgo

From Arcturus, continue following that arc — about another fist-length — and you’ll find Spica, the brightest star in Virgo.

Spica stands out in the southern sky as the fifteenth brightest star in the night sky. Although it appears as a single point of light, it’s actually two stars: a blue supergiant and a blue subgiant orbiting each other about 260 light-years from Earth.

Spica marks the lower edge of Virgo. If you imagine Virgo as a long, reclining figure stretched across the sky, Spica shines at her base. On a clear night, you might spot eight to ten stars forming her outline, though the full shape can be faint.

Virgo comes from the Latin for “virgin” and represented the goddesses of harvest, fertility and justice in ancient Greek mythology. Just to the right of Virgo lies the Virgo Supercluster, a vast grouping of around 2,000 galaxies, about 54 million light-years away from Earth. With a good amateur telescope, you might spot some of its brightest members.

Now swing back to the Big Dipper to track down one more constellation.

Find Leo – The Lion

Look at the two stars on the left edge of the Big Dipper’s bowl. From there, draw a diagonal line downward and to the right (southwest), roughly the length of two outstretched hands held side by side. You’ll arrive at Regulus, the brightest star in Leo.

Leo is easy to spot. Look for a backwards question mark of stars called The Sickle, with Regulus at the base, marking the lion’s heart. Behind it, a triangle of stars forms the lion’s body and tail.

Regulus means “little king”. It’s actually a system of four stars about 80 light-years away, with a sharp blue-white glow that stands out clearly in the spring night sky.

Together, Arcturus, Spica, and Regulus form the Spring Triangle — a seasonal asterism that rises high overhead in the evening sky during spring.

What else to spot in the night sky this May

There’s more to May than constellations. The spring sky also offers a series of impressive celestial events — no telescope required:

6 May – Eta Aquariid Meteor Shower

To experience this remarkable display at its peak, look southeast after 3 am. Up to 50 meteors an hour will light up the predawn sky, a breathtaking event caused by the remnants of Halley’s Comet, last visible in 1986 and not returning until 2061. If you happen to miss the peak date, don’t worry; you can still catch glimpses of the meteors until the end of May, though they will be less intense.

12 May – Flower Moon

The full moon rises in the southeast just after 9:15 pm. Known as the Flower Moon, it may appear extra-large near the horizon—a beautiful illusion caused by its low angle in the sky.

23 May – Moon Meets Venus and Saturn

Just before sunrise, look east. A slender crescent moon will be flanked by two bright planets: Venus on the left and Saturn on the right.

28 May – Moon Meets Jupiter

After sunset, look west. A thin waxing crescent moon will appear above brilliant Jupiter—a pairing too pretty to miss.

Looking for other stellar astronomy tips? My article – How to get more constellations than Orion under your belt – might help.

Omara Williams is a nuclear and software engineer whose multi-award-winning debut science-fiction novel, The Space Traveller’s Lover, shot to international bestseller status. Outside of her literary pursuits, she enjoys stargazing and chasing total solar eclipses.

Main Image: Courtesy Roberto Mura, via Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

RECENT ARTICLES

-

Why Europe still needs America

Why Europe still needs America -

Why Europe’s finance apps must start borrowing from each other’s playbooks

Why Europe’s finance apps must start borrowing from each other’s playbooks -

Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes

Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes -

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others -

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again -

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart?

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart? -

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing -

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage -

The limits of good intentions in public policy

The limits of good intentions in public policy -

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament?

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament? -

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth -

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours -

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality -

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now -

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day -

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy -

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it -

What if he falls?

What if he falls? -

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world -

Will Trump’s Davos speech still destroy NATO?

Will Trump’s Davos speech still destroy NATO? -

Philosophers cautioned against formalising human intuition. AI is trying to do exactly that

Philosophers cautioned against formalising human intuition. AI is trying to do exactly that -

Life’s lottery and the economics of poverty

Life’s lottery and the economics of poverty -

On a wing and a prayer: the reality of medical repatriation

On a wing and a prayer: the reality of medical repatriation -

Ai&E: the chatbot ‘GP’ has arrived — and it operates outside the law

Ai&E: the chatbot ‘GP’ has arrived — and it operates outside the law -

Keir Starmer, Wes Streeting and the Government’s silence: disabled people are still waiting

Keir Starmer, Wes Streeting and the Government’s silence: disabled people are still waiting