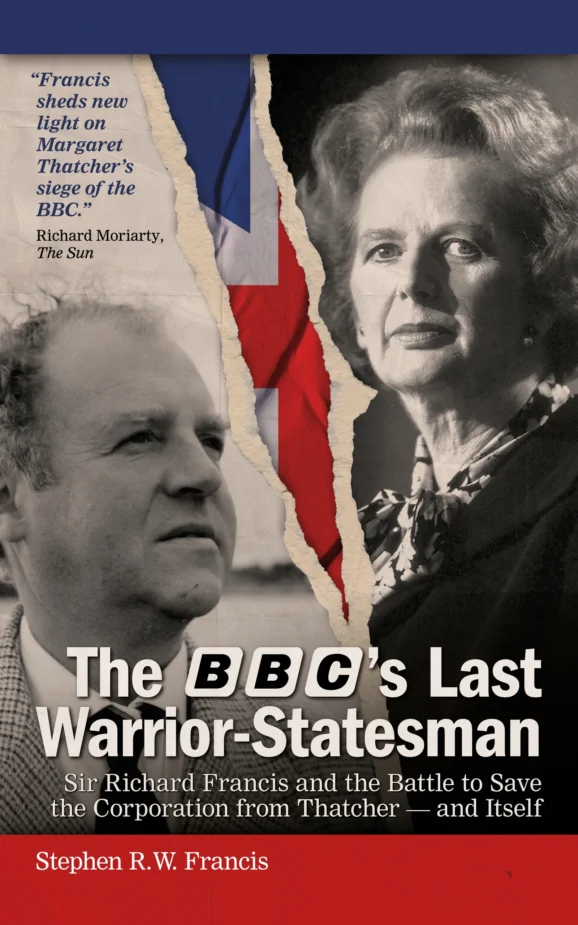

Stephen R.W. Francis on his new book, The BBC’s Last Warrior-Statesman

John E. Kaye

- Published

- Opinion & Analysis

John E.Kaye speaks to author Stephen R.W. Francis about his new memoir of Sir Richard Francis, his father’s clash with Thatcher over the BBC’s independence, and why fearless journalism still matters

During the 1970s and ’80s, Sir Richard ‘Dick’ Francis navigated some of the most volatile chapters in British broadcasting history. As a senior BBC executive, he authorised fuel convoys through IRA checkpoints to keep cameras rolling during The Troubles, approved the airing of controversial documentaries – including one featuring the voices of a murdered MP’s killers – and resisted political pressure at the highest level, even when it came from Margaret Thatcher herself. His unswerving commitment to editorial independence helped define the BBC’s public service ethos at a time when it was under siege.

Now, in The BBC’s Last Warrior-Statesman, his son Stephen R.W. Francis offers the first memoir of a man who fought not just for the Corporation, but for its soul. In this interview, Stephen reflects on his father’s legacy, the dangers of political interference, and why the BBC still needs warrior-leaders today.

Q. Why did you decide to write this book about your father now, more than 30 years after his passing?

A. Dad died before the internet age, and there was very little about him online, but he left 450 postcards and letters from over 100 countries. I discovered a lockup garage unopened in nearly 30 years — a jumble of golf bags, tapes, toys, and documents. It turned out to be a treasure trove. Over two years of research, I unearthed extraordinary material. What started as a family book became a broader history of the BBC during a turbulent era, capturing the core of public service broadcasting.

Q. How did your view of your father change during your research?

A. It didn’t change much, which was oddly comforting — more a case of black-and-white becoming colour. His personality traits live on in his sons: a love of travel, liberal values, stubbornness, and a strong sense of duty. He enjoyed parties and the stage, but was essentially shy, modest, and emotionally guarded. I saw more clearly his pushiness and, later, the blind doggedness that dulled his political antennae. Some mysteries were solved, others remain.

Q. Which event had the greatest impact on him?

A. Northern Ireland in the 1970s shaped him more than anything else. At 39, he became BBC Controller, Northern Ireland — his first command role, and a poisoned chalice. He ignored religion and got on with the job, bringing calm analysis to a pressure cooker of bombs and criticism. It transformed him into a skilled diplomat and leader. He loved Irish culture and despite being bombed and held at gunpoint, he and his wife, Penny, felt part of the Ulster community. His 1977 Chatham House talk, Broadcasting to a Community in Conflict, became a landmark statement of BBC policy.

Q. Is conflict between government and public broadcasters inevitable?

A. Yes. The BBC’s job is to hold power to account — and the government is at the centre of that. From the 1960s to Thatcher’s election in 1979, BBC journalism toughened, with interviewers like Robin Day skewering ministers live on air. Thatcher saw the BBC as arrogant and wasteful. Her agenda was to break its hold. The collision was inevitable.

Q. Was there a moment that best showed your father’s commitment to editorial independence?

A. In May 1982, during the Falklands War, Thatcher wanted the BBC to act as a patriotic mouthpiece. Francis told his journalists to stay objective. When Jon Snow used the term “unverified reports from British forces”, Thatcher erupted. The press supported “Maggie’s boys” with headlines like “GOTCHA”. Francis, in Madrid at the time, hit back: “The widow of Portsmouth is no different from the widow of Buenos Aires. The BBC needs no lessons in patriotism.” His boss, Alasdair Milne, called the intervention “unhelpful” but Francis never flinched from defending the BBC’s principles.

Q. How do today’s pressures on the BBC compare with those in the Thatcher era?

A. The parallels are striking. A reform-minded government, economic strain, and pressure to commercialise more of the BBC. The World Service is overstretched. Editorial standards are under pressure, and the BBC now operates more like a reactive news outlet. Its leadership is no longer drawn from the top tiers of British public life — those who have experience as diplomats and statesmen. It has lost ground abroad and appears to have retreated from its role as a voice of British soft power.

Q. What was the biggest revelation from your personal archive research?

A. The amount of ‘BBC confidential’ material was astonishing — especially the audio from Alasdair Milne’s August 1985 call defending the Real Lives ban. It captured the crisis in real time. I also found detailed documentation from Francis building his defence as his position crumbled. The files, including those labelled “Official Secrets Act,” showed the full scale of the conflict. And I found that after resigning in 1967, he was travelling under a pseudonym in Central Africa using a BBC credit card. Was he informally working for MI6? I still don’t know.

Q. What should modern journalists take from your father’s legacy?

A. Learn the rules, then be bold. BBC journalists have huge freedom but with that comes the obligation to be accurate, balanced and uphold the Charter. Don’t editorialise or chase popularity. Understand why the BBC exists and stand up to power when needed. The leadership today too often stays silent. My father believed the BBC should be confident, principled and visible — never cowed.

Q. What should readers unfamiliar with your father’s era take away from the book?

A. We’re living in a fragile moment. Institutions like the BBC matter more than ever. The book shows why the BBC earned its global trust through fearless journalism, independence and talent. It also shows how easily that position can slip. It’s a serious account of a serious era, but also a great yarn about a larger-than-life character — the last of the cigar-chomping, Concorde-travelling BBC men.

Main photo: Sir Richard Francis was a war producer for the BBC in the 1960s, filing dispatches from countries in conflict including Vietnam. (Stephen R.W Francis)

Sign up to The European Newsletter

RECENT ARTICLES

-

The lost frontier: how America mislaid its moral compass

The lost frontier: how America mislaid its moral compass -

Why the pursuit of fair taxation makes us poorer

Why the pursuit of fair taxation makes us poorer -

In turbulent waters, trust is democracy’s anchor

In turbulent waters, trust is democracy’s anchor -

The dodo delusion: why Colossal’s ‘de-extinction’ claims don’t fly

The dodo delusion: why Colossal’s ‘de-extinction’ claims don’t fly -

Inside the child grooming scandal: one officer’s story of a system that couldn’t cope

Inside the child grooming scandal: one officer’s story of a system that couldn’t cope -

How AI is teaching us to think like machines

How AI is teaching us to think like machines -

The Britain I returned to was unrecognisable — and better for It

The Britain I returned to was unrecognisable — and better for It -

We built an education system for everyone but disabled students

We built an education system for everyone but disabled students -

Justice for sale? How a £40 claim became a £5,000 bill in Britain’s broken Small Claims Court

Justice for sale? How a £40 claim became a £5,000 bill in Britain’s broken Small Claims Court -

Why control freaks never build great companies

Why control freaks never build great companies -

I quit London’s rat race to restore a huge crumbling estate in the Lake District

I quit London’s rat race to restore a huge crumbling estate in the Lake District -

The grid that will decide Europe’s future

The grid that will decide Europe’s future -

Why Gen Z struggles with pressure — and what their bosses must do about it

Why Gen Z struggles with pressure — and what their bosses must do about it -

What Indian philosophy can teach modern business about resilient systems

What Indian philosophy can teach modern business about resilient systems -

AI can’t swim — but it might save those who do

AI can’t swim — but it might save those who do -

The age of unreason in American politics

The age of unreason in American politics -

Digitalization, financial inclusion, and a new era of banking services: Uzbekistan’s road to WTO membership

Digitalization, financial inclusion, and a new era of banking services: Uzbekistan’s road to WTO membership -

Meet Omar Yaghi, the Nobel Prize chemist turning air into water

Meet Omar Yaghi, the Nobel Prize chemist turning air into water -

Behind the non-food retail CX Benchmark: what the numbers tell us about Europe’s future

Behind the non-food retail CX Benchmark: what the numbers tell us about Europe’s future -

Why NHS cancer care still fails disabled people

Why NHS cancer care still fails disabled people -

Echoes of 1936 in a restless and divided Britain

Echoes of 1936 in a restless and divided Britain -

Middle management still holds the power leaders need

Middle management still holds the power leaders need -

Trump and painkillers: The attack on science is an attack on democracy

Trump and painkillers: The attack on science is an attack on democracy -

The end of corporate devotion? What businesses can learn from Gen Z

The end of corporate devotion? What businesses can learn from Gen Z -

Britain’s free speech crisis: the weaponisation of complaints and the erosion of police discretion

Britain’s free speech crisis: the weaponisation of complaints and the erosion of police discretion