Innovation off the grid

John E. Kaye

- Published

- Home, Sustainability

When Dr Jemma Green returned to her native Perth after spending eight years in London, where she worked as an investment banker, she was astonished by the scarce use of solar energy in a sun-drenched country such as Australia. “One of the things I noticed was that hardly any apartments, which make up 30% of the housing stock in Australia, had solar panels,” says Dr Green. Knowing that apartment blocks could operate as energy retailers without the need for a licence, Dr Green designed a network to enable households to generate and trade solar energy, as a part of her doctoral research.

While trying to find a software programme that would support the network, Dr Green was introduced to two blockchain developers. They told her about the blockchain, a form of online distributed ledger that records transactions and the technology underpinning cryptocurrencies. She was sceptical to begin with.

“I actually thought it was all a bit science fiction at first, but I asked if there were any applications for the electricity sector,” Dr Green says. She soon realised that the technology could allow households to bypass intermediaries and trade solar energy.

Along with one of the developers, John Bulich, and an expert in the electricity industry, David Martin, she launched Power Ledger in 2017, a platform using blockchain to facilitate energy trading. The company has raised over $34m via an initial coin offering and has won Sir Richard Branson’s Extreme Tech Challenge.

“Power Ledger was created to enable a marketplace so [that] renewable energy can be affordable, low-carbon and available to everyone around the world,” says Dr Green, who believes in the power of technology to make our economy greener. “Blockchain presents an opportunity to monetise carbon and renewable energy credits sooner. Historically, monetising credits has been a difficult job, especially for the sellers who had to navigate mountains of paperwork, processes and fragmented thinking.”

Participants in the fledgling market install a sensor connected to a digital energy meter that tracks the amount of energy created, bought or sold and converts it into tokens. Those equipped with solar panels and batteries can sell excess energy to their neighbours or

to energy companies.

Power Ledger is not the only company active in this area. The German startup Lition has developed a blockchain-enabled peer-to-peer marketplace that enables participants to purchase energy directly from renewable energy power stations with green credentials, cutting out the middleman.

The blockchain can turn energy consumers into producers, Dr Green believes: “Blockchain enables us to fractionalise community-scale renewable energy assets, which allows everyday investors to own a piece of tomorrow’s energy systems. It means that for the first time, everyday people can invest in and co-own large-scale renewable assets like solar farms and batteries, with less up-front capital while receiving a return.”

Smartening up the grid

Perhaps the blockchain’s most celebrated use in the energy sector is powering smart micro-grids: independent, localised energy grids for renewable energy resources. The very nature of the technology lends itself to such an innovation, says Mark van Rijmenam, founder of the startup Datafloq and the author of Blockchain: Transforming Your Business and Our World: “Since selling or buying energy is basically a transaction, it is perfectly suitable for the blockchain to make these peer-to-peer transactions in a ‘trustless’ environment immutable, verifiable and traceable,” he says. “A micro-grid creates a great incentive to move towards renewable energy and install solar panels or windmills, as it offers an additional return on the initial investment.”

Optimists hope that the blockchain can help decentralise an energy sector that is too centralised and sclerotic for the needs of a green economy. Electrical grids have been designed around large, centralised power plants that send electricity to millions of consumers, whereas renewable power plants – such as wind farms and solar parks – tend to be small, scattered and supporting energy flows in multiple directions.

Blockchain-enabled micro-grids, can serve as loosely connected local networks, responsive to changes in demand and supply. Professor Peter Fox-Penner, Director of the Institute for Sustainable Energy at

Boston University, says: “For the first time, parts of the grid will be technologically and fiscally able to decouple from the grid. Up until now, the grid has been one integrated, unitary whole, with common technical standards and social roles.”

There are some risks, however, Professor Fox-Penner remarks: “As micro-grids are able to separate, the reliability and resilience experienced by customers may differ, and now be sold as an incremental service. This is good, but not if it undermines the social compact of a common minimum level of service to all electric customers.” Some form of centralised oversight will still be necessary, he adds: “The nature of the electric power system is such that central authorities will have to have visibility into all trades made on any power grid in order to ensure the grid continues to function. So, while the grid operator may not see the trading price, they will have to ‘OK’ that the trade takes place and will be able to disallow it on reliability grounds.”

One of blockchain’s main assets is that it enables energy trading at industrial scale, says David Shipworth, Professor of Energy and the Built Environment at UCL Energy Institute: “Blockchains create digital scarcity – that is, they create a zero-sum game in which units of energy can be exchanged within the energy system without the risk of double spending by unscrupulous parties. They can, at least in principle, also dramatically reduce transaction costs. This is essential if we are doing large numbers of small value trades in order to balance the grid. There is no point in trading a few kilowatt-hours of electricity unless the cost of doing so is virtually negligible.”

Transparency is another key factor, according to Professor Shipworth: “Blockchains also offer advantages in terms of creating an environment in which parties that do not trust each other can engage in a market on the basis of clear and transparent rules. Lack of trust between participants in the market, energy suppliers and consumers is a characteristic of the current energy market.”

Empowering consumers

Βlockchain enthusiasts hope that technology can be a powerful tool in the fight against climate change. One example of this process is a blockchain solution developed by the Finnish energy company Fortum, to help customers link consumption to weather forecasts by automatically adjusting their house temperatures. In the developing world, distributed ledgers can help consumers reduce energy costs. In South Africa, the existence of various middlemen in the energy market results in high billing prices. To tackle the problem, the South African startup Bankymoon has developed blockchain-enabled smart meters for consumers to pre-pay their energy bills using cryptocurrencies, since many of them don’t have a bank account. Consumers use cryptocurrency wallets attached to their smart meters to receive credits corresponding to their energy consumption. “Such a solution will empower Africans, making them more aware of their energy consumption, which, in the long-run, could reduce their energy consumption,” says Mr Van Rijmenam of Datafloq.

Another way the blockchain can reduce carbon emissions is by facilitating the establishment of Virtual Power Plants (VPPs): decentralised networks connecting various energy producing units such as wind farms and solar parks. The South Korean government announced in December that it will invest KRW 4bn (approximately $3.5m) to create a public blockchain-enabled VPP in Busan. Power Ledger is also trialling its own VPP in partnership with KEPCO, a Japanese electric utility. However, sceptics play down the blockchain’s contribution: “At a high level, they [VPPs] do not appear very unique; retail load aggregators have been creating VPPs without blockchain for some time now,” says Professor Fox-Penner of Boston University.

On a macro scale, the blockchain can help countries optimise carbon emissions trade, a market expected to grow be worth $3.5tn by 2020, according to Chinese government data. In 2016, a partnership between IBM and the Beijing Energy-Blockchain Labs resulted in the first blockchain platform for carbon trading in China. The objective is to make management and trade of carbon assets more efficient and transparent, as well as reduce carbon emissions. Dr Green says: “Today, the cost-effectiveness of renewable energy systems, coupled with ratifications such as the Paris Agreement – where countries have mandated a move to zero-carbon energy production to fight against climate change – provide an economic motivation for governments to adopt clean energy systems, and blockchain can help facilitate and fast-track this growth.”

However, some uses of the blockchain can be ecologically deleterious. To produce digital coins that utilise a “proof-of-work” consensus mechanism, such as the bitcoin, cryptocurrency users need to carry out complex computations and thus consume an ever-increasing amount of energy. The recent cryptocurrency mania has also sparked the creation of several “mining farms” in Russia, China and other countries that generate bitcoin and other currencies on industrial levels. Professor Fox-Penner says: “Blockchain has begotten bitcoin, and bitcoin mining is now reportedly using as much energy as the country of Denmark. To the extent that this energy comes from fossil-fuelled electricity is terrible for the climate, and to the extent this energy comes from clean sources it is questionable as to whether that clean power should be better used now for decarbonising other sectors of the economy, notably industrial emissions.”

Many other cryptocurrencies have appeared that use different consensus mechanisms, such as “proof of stake” or “proof of authority,” that require far less energy. According to Professor Shipworth, the technology is already adjusting to the needs of the green economy: “One analogy I use is that just as dinosaurs evolved into birds, so bitcoin’s heavy and cumbersome consensus mechanism is evolving into something much faster and lighter.”

For more world energy news, follow The European

RECENT ARTICLES

-

Strong ESG records help firms take R&D global, study finds

Strong ESG records help firms take R&D global, study finds -

How residence and citizenship programmes strengthen national resilience

How residence and citizenship programmes strengthen national resilience -

Global leaders enter 2026 facing a defining climate choice

Global leaders enter 2026 facing a defining climate choice -

EU sustainability rules drive digital compliance push in Uzbekistan ahead of export change

EU sustainability rules drive digital compliance push in Uzbekistan ahead of export change -

China’s BYD overtakes Tesla as world’s largest electric car seller

China’s BYD overtakes Tesla as world’s largest electric car seller -

UK education group signs agreement to operate UN training centre network hub

UK education group signs agreement to operate UN training centre network hub -

Mycelium breakthrough shows there’s mush-room to grow in greener manufacturing

Mycelium breakthrough shows there’s mush-room to grow in greener manufacturing -

Oxford to host new annual youth climate summit on UN World Environment Day

Oxford to host new annual youth climate summit on UN World Environment Day -

Exclusive: Global United Nations delegates meet in London as GEDU sets out new cross-network sustainability plan

Exclusive: Global United Nations delegates meet in London as GEDU sets out new cross-network sustainability plan -

Fast fashion brands ‘greenwash’ shoppers with guilt-easing claims, study warns

Fast fashion brands ‘greenwash’ shoppers with guilt-easing claims, study warns -

Private sector set to overtake government as main driver of corporate sustainability in 2026, report suggests

Private sector set to overtake government as main driver of corporate sustainability in 2026, report suggests -

Sir Trevor McDonald honoured at UWI London Benefit Dinner celebrating Caribbean achievement

Sir Trevor McDonald honoured at UWI London Benefit Dinner celebrating Caribbean achievement -

Historic motorsport confronts its energy future

Historic motorsport confronts its energy future -

Protecting the world’s wild places: Dr Catherine Barnard on how local partnerships drive global conservation

Protecting the world’s wild places: Dr Catherine Barnard on how local partnerships drive global conservation -

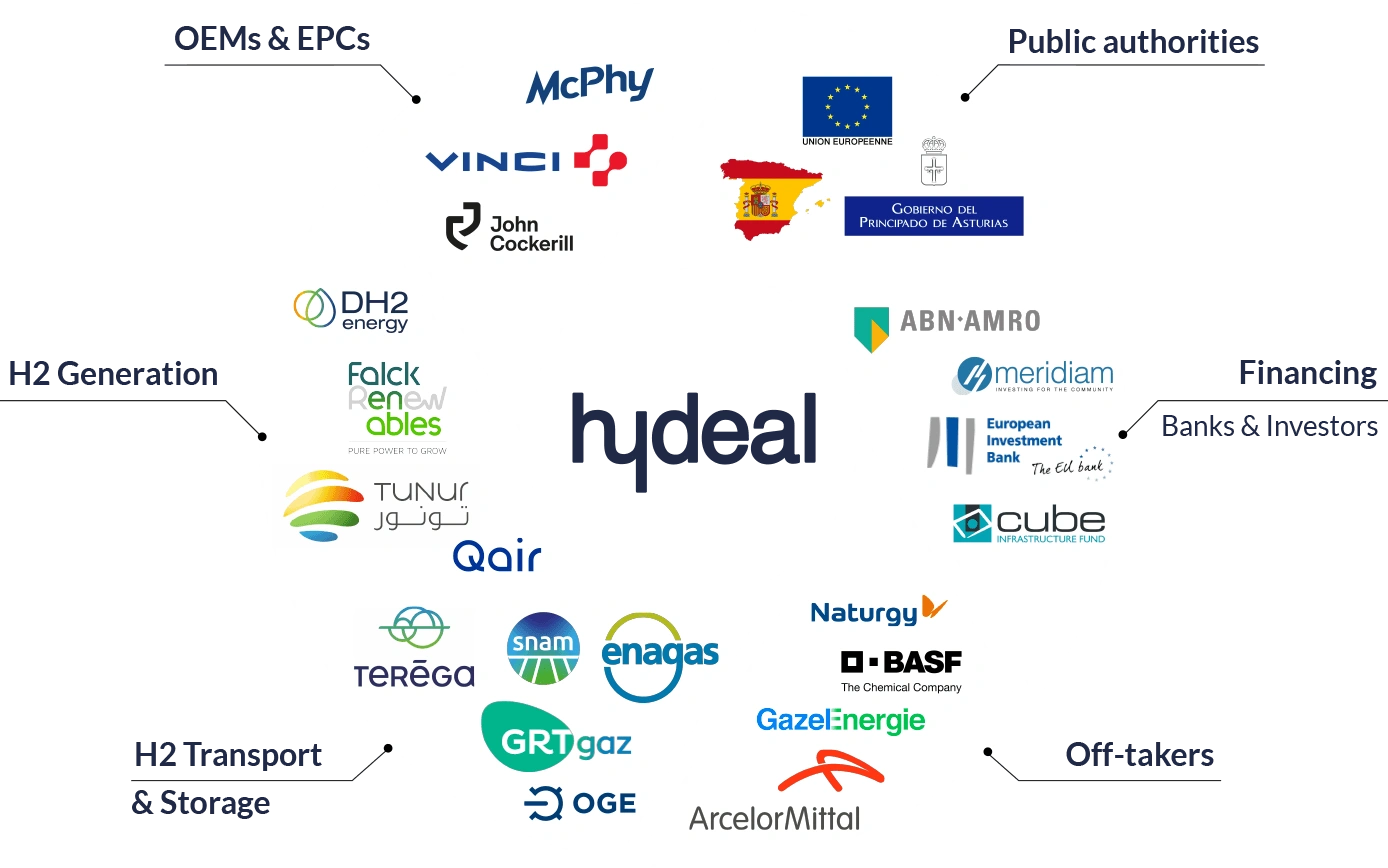

Europe’s HyDeal eyes Africa for low-cost hydrogen link to Europe

Europe’s HyDeal eyes Africa for low-cost hydrogen link to Europe -

Fabric of change

Fabric of change -

Courage in an uncertain world: how fashion builds resilience now

Courage in an uncertain world: how fashion builds resilience now -

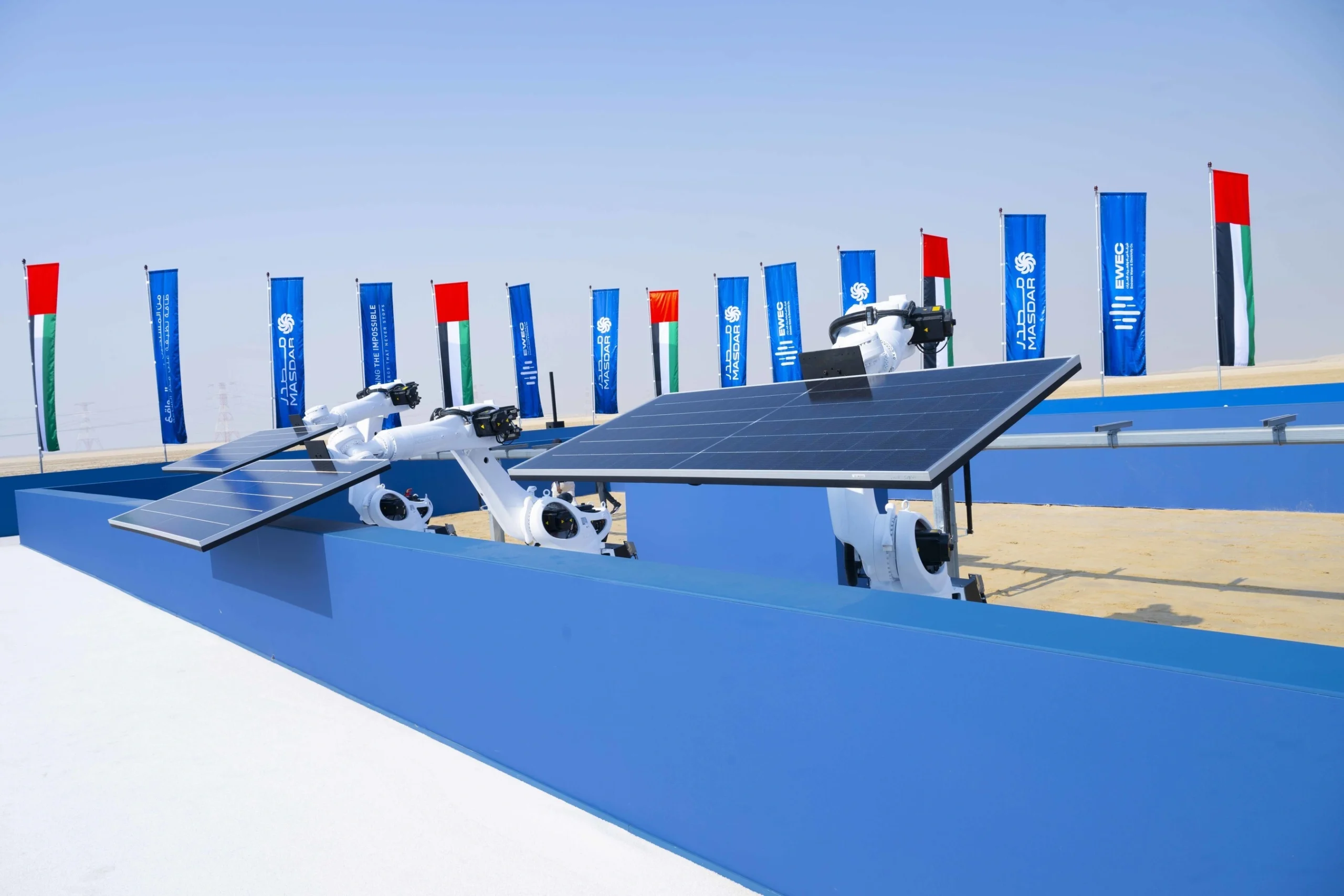

UAE breaks ground on world’s first 24-hour renewable power plant

UAE breaks ground on world’s first 24-hour renewable power plant -

China’s Yancheng sets a global benchmark for conservation and climate action

China’s Yancheng sets a global benchmark for conservation and climate action -

Inside Iceland’s green biotechnology revolution

Inside Iceland’s green biotechnology revolution -

Global development banks agree new priorities on finance, water security and private capital ahead of COP30

Global development banks agree new priorities on finance, water security and private capital ahead of COP30 -

UK organisations show rising net zero ambition despite financial pressures, new survey finds

UK organisations show rising net zero ambition despite financial pressures, new survey finds -

Gulf ESG efforts fail to link profit with sustainability, study shows

Gulf ESG efforts fail to link profit with sustainability, study shows -

Redress and UN network call for fashion industry to meet sustainability goals

Redress and UN network call for fashion industry to meet sustainability goals -

World Coastal Forum leaders warn of accelerating global ecosystem collapse

World Coastal Forum leaders warn of accelerating global ecosystem collapse