Fresh energy needed for Europe’s nuclear debate

John E. Kaye

- Published

- Energy, Home, Sustainability

European wranglings over nuclear as a “sustainable” energy source reflect military pressures – an aspect that remains little discussed, say Andy Stirling and Phil Johnstone of the University of Sussex Business School

Whatever one’s view of nuclear issues, an open mind is crucial. Massive vested interests and media clamour require efforts to view a bigger picture. A case in point arises around the European Commission’s much criticised proposal last year – and the European Parliament’s strongly opposed decision – to accredit nuclear power as a “green” energy source. In a series of legal challenges, the European Commission and NGOs including Greenpeace are tussling over what kind and level of “sustainability” nuclear power might offer.

To understand how an earlier more sceptical EC position on nuclear was overturned, deeper questions are needed about a broader context. Recent moves in Brussels follow years of wrangling. Journalists reported intense lobbying – especially by the EU’s only nuclear-armed nation: France. At stake is whether inclusion of nuclear power in the controversial “green taxonomy” will open the door to major financial support for “sustainable” nuclear power.

Notions of sustainability were (like climate concerns) pioneered in environmentalism long before being picked up in mainstream policy. And – even when its comparative disadvantages were less evident – criticism of nuclear was always central to green activism. So, it might be understood why current efforts from outside environmentalism to rehabilitate nuclear as “sustainable” are open to accusations of greenwashing and doublespeak.

In sync with the UN’s SDGs?

In deciding such questions, the UN’s internationally-agreed Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) provide a key guide. These address various issues associated with all energy options – including costs and wellbeing, health effects, accident risks, pollution and wastes, landscape impacts and disarmament issues. So, do such comparative pros and cons of nuclear power warrant classification alongside wind, solar and efficiency?

On some aspects, the picture is relatively open. All energy investments yield employment and development benefits, largely in proportion to funding. On all sides, simply counting jobs or cash flowing through favoured options and forgetting alternatives leads to circular arguments. If – despite being highlighted in the Ukraine war – unique vulnerabilities of nuclear power to attack are set aside, then the otherwise largely “domestic” nature of both nuclear and renewables can be claimed to be comparable.

Orderings are more stark on economics and environment. Despite room for many views, it is difficult to deny that history raises especially grave queries about nuclear power. Nuclear costs have long been acknowledged to be far less competitive than renewables. Multiple nuclear accidents have occurred, of kinds initially claimed to have “negligible” likelihood. Nuclear waste “solutions” are still largely undeveloped. New questions continually arise about assumptions underpinning “safe levels” of ionising radiation. Build times far exceeding those promised have helped cause nuclear bankruptcy and fraud. Growth rates of renewables surpass what government officials even quite recently claimed to be physically possible. Associated trends nearly all favour renewables.

But what of climate urgency? Does this not justify calls by nuclear proponents to “do everything” to “keep the nuclear option open” – as if this were an end in itself? Again: deeper thought might expose this as special pleading. Precisely because climate action is so imperative, isn’t it more rational to prioritise whatever is most substantial, cost effective and rapid?

A more reasoned approach might ask about long-neglected kinds of statistical analysis, which show that national carbon emission reductions tend to associate less with nuclear than with renewable uptake. Key reasons here include that nuclear contributions to climate targets are smaller, slower and more expensive than are offered by renewables. So, other evidence that nuclear and renewable energy strategies also tend to conflict further questions the sustainability status of nuclear power.

What then of claimed needs for “baseload” power – to manage variable outputs from some renewables? Surprisingly given its public profile, this notion is long abandoned by the electricity industry as outdated. Nuclear power is itself inflexible in its own way. Myriad system innovations, grid improvements, demand measures and new storage technologies are all available to better address variable renewables over different timescales. Even in relatively pro-nuclear UK, it is authoritatively documented how a 100% renewable system outperforms any level of nuclear contribution. Even the UK government now admits that adding these costs still leaves renewables outcompeting nuclear. In less nuclear-committed European countries, the picture is even more stark.

The big question

So, as this picture has unfolded, nuclear “sustainability” arguments have retreated through successively undermined claims – that nuclear is “necessary”; brooks “no alternative”; is “more competitive”; uniquely offers to “keep the lights on”; or is just a way to “do everything” (as if this was ever a sensible response to any challenge, especially one as urgent and existential as climate disruption).

Whatever position one starts from, then, a final question arises: why all the fuss? Why should it be now after all these years – just as its comparative performance becomes so much less favourable – that European efforts become so newly energetic to redefine nuclear as “sustainable”? Why is it so difficult to recognise that – as is normal with technologies – nuclear energy is obsolescing?

Here, the answer is surprisingly obvious. It is officially repeatedly confirmed in countries working hardest to revive nuclear power – atomic weapons states like the US, France, the UK, Russia and China. Oddly neglected in mainstream energy policy and the media, the picture is especially evident on the defence side. Although skewed public debates leave many unaware, nuclear affections are a military romance. Powerful defence interests – with characteristic secrecy and highly active PR – are mostly driving the dogged persistence.

The result is clear. Dubiously justified in climate terms, elevated consumer prices, government funding and public risk underwriting all help maintain a joint civil/military “nuclear industrial base”. In nuclear-armed countries like the UK and France, this helps fund – outside defence budgets, off the public books and away from due scrutiny – expensive specialist nuclear skills, supply chains, research facilities, navy recruitment, wider infrastructures. In particular, the building and operating of nuclear propelled submarines would be unaffordable without these concealed cross-subsidies. Without nuclear power, it would become much harder to guarantee the later careers that are so essential in recruiting nuclear-trained officers.

As President Macron recently said: “Without civilian nuclear, no military nuclear, without military nuclear, no civilian nuclear.” This is the main reason why France is pressing so hard for nuclear to be supported by the European Union as sustainable. This is why non-nuclear-armed Germany has been more open to grasping nuclear realities. This is why France and Germany find themselves at such loggerheads on this issue. This is why the UK government so opposes this – and is so fixated on support for general nuclear skills. This is why other nuclear-armed states in general, are so resolutely fixated by the slow, small and costly nuclear response to the climate emergency.

A decision has yet to be reached on whether the inclusion of nuclear by the European Commission in their Green Taxonomy is unlawful. Yet it is clear that nuclear compares poorly to other low carbon technologies when considered in terms of sustainability. What is especially concerning is that the military rationales that are influencing renewed enthusiasm for nuclear are largely unaddressed in policy and wider media coverage. That associated issues are so little discussed, raises grave concerns not just for energy and climate policy, but for European democracy as a whole.

About the authors

Andrew Stirling (left) is Professor of Science and Technology Policy at the University of Sussex Science Policy Research Unit (SPRU), and a professor at the University of Sussex Business School. Philip Johnstone is a Senior Research Fellow at the SPRU.

RECENT ARTICLES

-

Strong ESG records help firms take R&D global, study finds

Strong ESG records help firms take R&D global, study finds -

How residence and citizenship programmes strengthen national resilience

How residence and citizenship programmes strengthen national resilience -

Global leaders enter 2026 facing a defining climate choice

Global leaders enter 2026 facing a defining climate choice -

EU sustainability rules drive digital compliance push in Uzbekistan ahead of export change

EU sustainability rules drive digital compliance push in Uzbekistan ahead of export change -

China’s BYD overtakes Tesla as world’s largest electric car seller

China’s BYD overtakes Tesla as world’s largest electric car seller -

UK education group signs agreement to operate UN training centre network hub

UK education group signs agreement to operate UN training centre network hub -

Mycelium breakthrough shows there’s mush-room to grow in greener manufacturing

Mycelium breakthrough shows there’s mush-room to grow in greener manufacturing -

Oxford to host new annual youth climate summit on UN World Environment Day

Oxford to host new annual youth climate summit on UN World Environment Day -

Exclusive: Global United Nations delegates meet in London as GEDU sets out new cross-network sustainability plan

Exclusive: Global United Nations delegates meet in London as GEDU sets out new cross-network sustainability plan -

Fast fashion brands ‘greenwash’ shoppers with guilt-easing claims, study warns

Fast fashion brands ‘greenwash’ shoppers with guilt-easing claims, study warns -

Private sector set to overtake government as main driver of corporate sustainability in 2026, report suggests

Private sector set to overtake government as main driver of corporate sustainability in 2026, report suggests -

Sir Trevor McDonald honoured at UWI London Benefit Dinner celebrating Caribbean achievement

Sir Trevor McDonald honoured at UWI London Benefit Dinner celebrating Caribbean achievement -

Historic motorsport confronts its energy future

Historic motorsport confronts its energy future -

Protecting the world’s wild places: Dr Catherine Barnard on how local partnerships drive global conservation

Protecting the world’s wild places: Dr Catherine Barnard on how local partnerships drive global conservation -

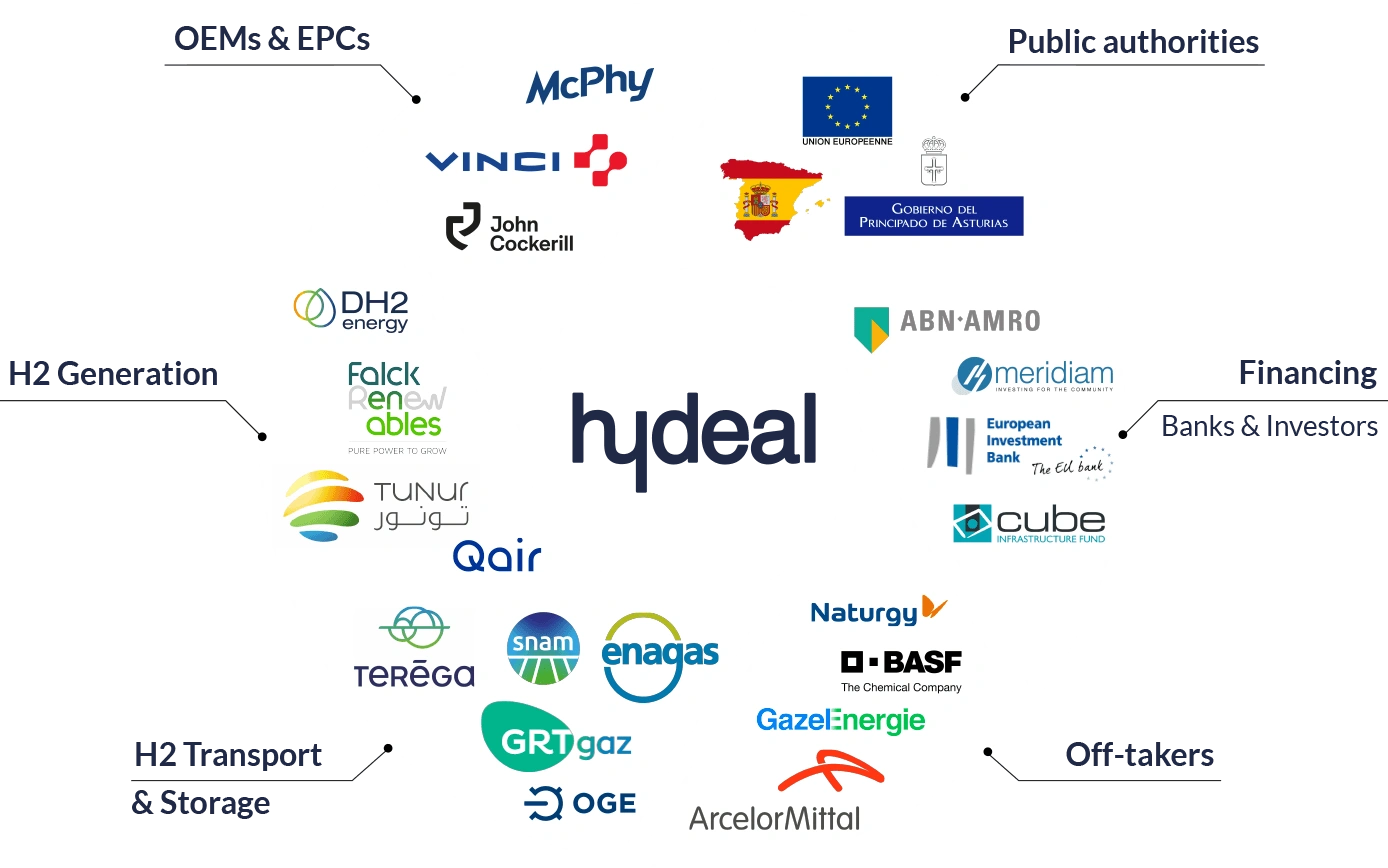

Europe’s HyDeal eyes Africa for low-cost hydrogen link to Europe

Europe’s HyDeal eyes Africa for low-cost hydrogen link to Europe -

Fabric of change

Fabric of change -

Courage in an uncertain world: how fashion builds resilience now

Courage in an uncertain world: how fashion builds resilience now -

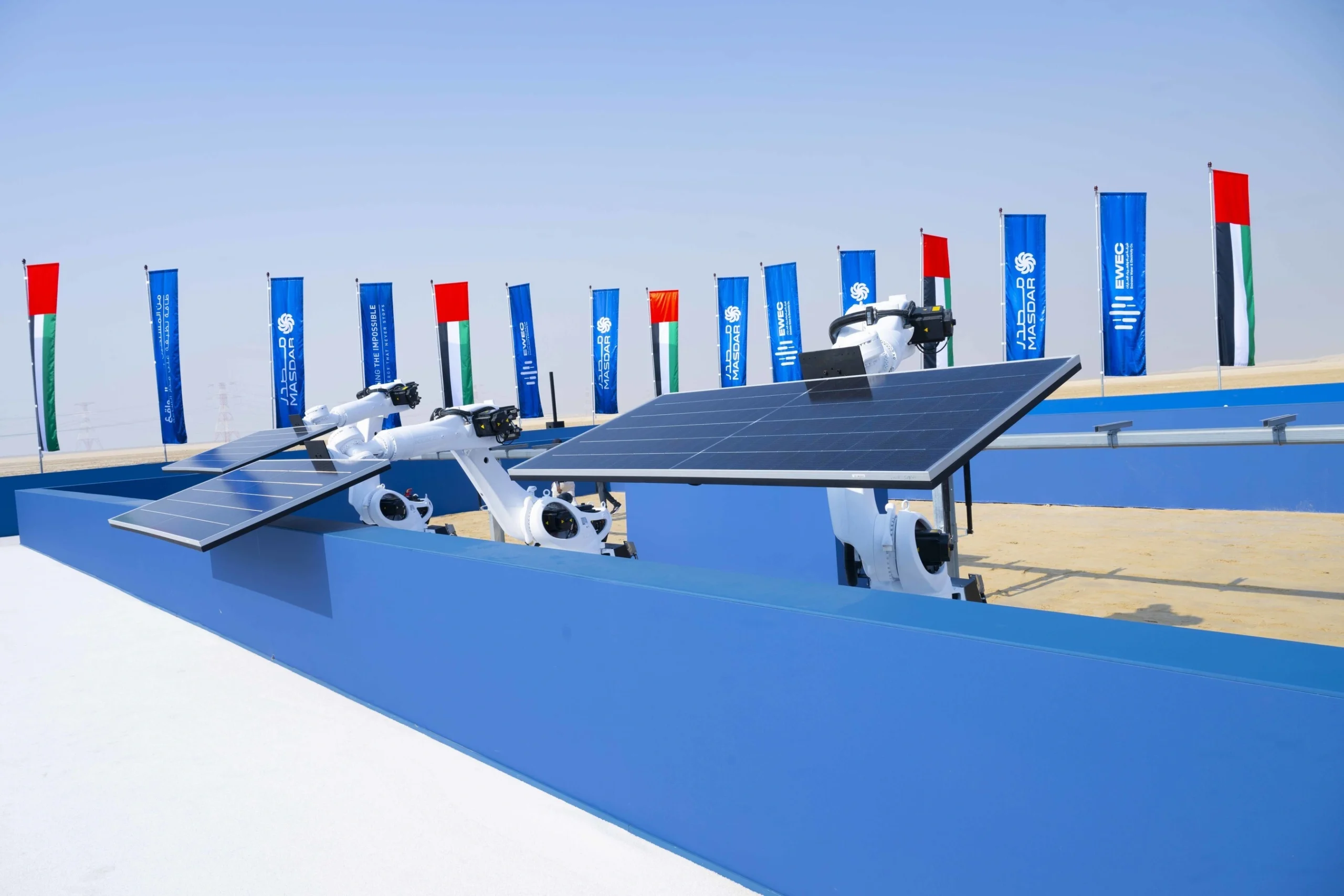

UAE breaks ground on world’s first 24-hour renewable power plant

UAE breaks ground on world’s first 24-hour renewable power plant -

China’s Yancheng sets a global benchmark for conservation and climate action

China’s Yancheng sets a global benchmark for conservation and climate action -

Inside Iceland’s green biotechnology revolution

Inside Iceland’s green biotechnology revolution -

Global development banks agree new priorities on finance, water security and private capital ahead of COP30

Global development banks agree new priorities on finance, water security and private capital ahead of COP30 -

UK organisations show rising net zero ambition despite financial pressures, new survey finds

UK organisations show rising net zero ambition despite financial pressures, new survey finds -

Gulf ESG efforts fail to link profit with sustainability, study shows

Gulf ESG efforts fail to link profit with sustainability, study shows -

Redress and UN network call for fashion industry to meet sustainability goals

Redress and UN network call for fashion industry to meet sustainability goals -

World Coastal Forum leaders warn of accelerating global ecosystem collapse

World Coastal Forum leaders warn of accelerating global ecosystem collapse