Takeaways from eco food study

John E. Kaye

- Published

- ESG, Home, Sustainability

New research to understand how consumers assess the environmental impact of their meals illustrates that colour-coded menus can deliver more sustainable choices, says Bianca Beyer of Aalto University School of Business

When the Paris Agreement was signed in 2016, the world agreed to limit global warming and fight climate change. But how do we internalise the challenges created by such an urgent and universal problem? Banning environmentally unfriendly processes and increasing prices for environmentally damaging products is often at the centre of heated debates among policymakers and regulators. But there is an alternative, much less invasive solution – providing consumers with information and simply letting “the market” decide.

The idea of using information to aid in better decision-making is not new. In the absence of a global environmental tax, and with only some countries implementing carbon pricing, the European Commission pins its sustainability hopes on disclosure.

In order to better inform investors and consumers about industry’s sustainability impacts, corporations will be mandated to provide comprehensive reports under the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive from 2024 onwards. By expanding the 2014 Non-Financial Reporting Directive from around 11,000 companies to almost 50,000, the amount of sustainability information being produced will increase substantially until 2029.

Information used by who and for what?

It is an old idea to let consumers vote with their feet in order to regulate markets. Still, the pressing question is how do consumers know which products to walk away from, and which to walk towards? Research shows that consumers greatly underestimate the carbon footprint of products they purchase. This is especially the case with food products.

As part of a research team comprising six experts from Aalto University School of Business, Humboldt University of Berlin and LMU Munich School of Management, I co-authored a study investigating how disclosing carbon footprint information affects diners’ food choices.

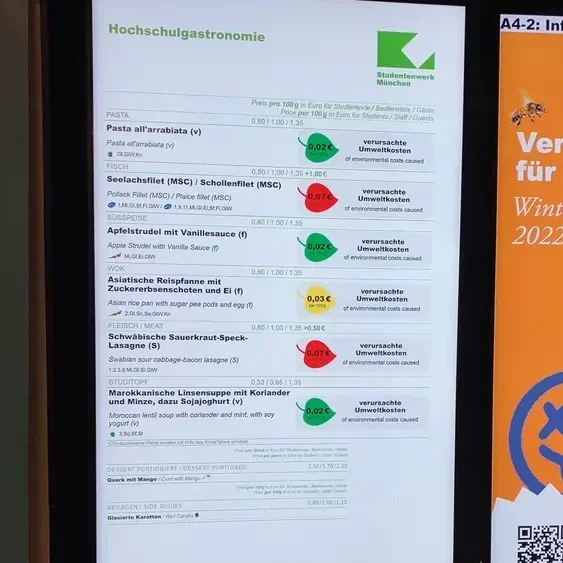

The study was based on a field experiment run in cooperation with Studentenwerk München, a large German student union which operates lunch canteens for students, staff and guests. This setting allowed us to observe around 2,500 consumers daily over a period of 10 days. For the experiment, we added information about each meal’s carbon footprint to the menu displays and monitored how this changed canteen people’s meal choices, gathering data on over 22,000 purchases. Because we were particularly interested in how, rather than just whether, diners would react, we also changed the way this information was presented throughout the experiment.

Besides simply displaying carbon dioxide emissions in grams for each meal, we also experimented with colour-coding using a traffic light system, with green representing low emissions etc. We also contextualised the level of emissions for each meal by representing it as a percentage of a typical person’s daily “carbon budget” for food, or as the “environmental cost” of producing each meal in euros.

Students in Germany were presented with menus complete with carbon footprint information

Presentation matters

Our findings give reason for hope – yes, people do change their behaviour and consume more environmentally-friendly meals when exposed to carbon footprint information. However, drawing conclusions for broader society is subject to a couple of limitations.

The participants in our experiment were a fairly homogenous group: young, well-educated and probably very environmentally conscious. So, it’s possible these results don’t accurately reflect broader society. This is because a higher interest in the environment might make this group more susceptible to the added information, while in other settings, such as the canteen of a manufacturing company, we might see a different consumer reaction. However, the participants in our experiment might also be more environmentally aware to begin with, and therefore less likely to be influenced by the additional information we provided.

While the overall effect in society may not be clear, we view our study as an important first step in showing that presentation matters when displaying carbon footprint information.

In a survey accompanying the main experiment, we asked consumers how they usually select their food – for instance by taste, appearance and price. Only 10.7% claimed that carbon footprint plays a role in what they decide to eat.

Yet, we observed a significant change in diners’ meal choices when they were informed about the carbon footprint of each dish. In particular, they were far less likely to choose dishes containing meat or fish, which are associated with high emissions.

This effect was strongest when we presented the information as environmental costs caused and used the traffic light system. Participants purchased 2.3% less food, were 7.1 percentage points less likely to select a meat or fish dish, and reduced their food-related carbon dioxide equivalent emissions by 9.2%.

The implication for policymakers is clear – it’s not just what is disclosed to consumers that matters, but also how.

Informing or influencing

So, what’s the difference between nudging consumers and just providing information? This is a grey area. Providing information in a specific way, for instance by emphasising its salience through traffic light colours as we did or sorting products into a specific order can be considered nudging. Policymakers must keep in mind that some people might be unhappy with the idea that they are being influenced to make a particular choice.

Indeed, when asked to rate their overall satisfaction with their food, respondents self-reported lower levels of happiness while carbon footprint information was provided on menus. This could be for several reasons. It’s possible that participants felt pressured into eating more sustainable food, or perhaps realising the extent of the environmental impact of their food choices caused them discomfort.

However, simply throwing an unprocessed load of numerical information at consumers passing by a food display might lead to this data being ignored altogether. It requires time and effort to digest which diners are likely not willing to invest in reading a menu.

So, it’s not surprising that we found the strongest impact on consumers when we increased the noticeability of the information by using a familiar colour scheme and made it easier to understand by framing emissions in terms of a monetary cost.

The key takeaway from our research for policymakers and regulators is that change does not have to be dramatic to have a significant impact. Widespread implementation of carbon emissions data on menus at canteens, cafes and restaurants could potentially lead to a sizeable reduction in a population’s food-related carbon footprint.

About the Author

Bianca Beyer is Assistant Professor at Aalto University School of Business.

RECENT ARTICLES

-

Jersey builds on regulatory strength to stay globally competitive

Jersey builds on regulatory strength to stay globally competitive -

Why hybrid energy systems are set to power the continent

Why hybrid energy systems are set to power the continent -

ees Europe: The rise of large-scale storage systems

ees Europe: The rise of large-scale storage systems -

From reputational risk to competitive advantage

From reputational risk to competitive advantage -

Take your business success full circle

Take your business success full circle -

Designed for life

Designed for life -

Is your ESMS fit for purpose?

Is your ESMS fit for purpose? -

Digitally enable your ESG solutions

Digitally enable your ESG solutions -

Afore SURA - The journey to sustainable investment

Afore SURA - The journey to sustainable investment -

ESG at IDFC FIRST Bank

ESG at IDFC FIRST Bank -

Takeaways from eco food study

Takeaways from eco food study -

It’s all about sustainability

It’s all about sustainability -

Invest in a Greener Tomorrow with Westbrooke Associates

Invest in a Greener Tomorrow with Westbrooke Associates -

Q&A with Cifi Asset Management's Ricardo Rico, Head of Funds & Javier Escorriola, Managing Partner

Q&A with Cifi Asset Management's Ricardo Rico, Head of Funds & Javier Escorriola, Managing Partner -

The present calls for sustainable investments, and CIFI has heard that call

The present calls for sustainable investments, and CIFI has heard that call -

The power to transform tomorrow

The power to transform tomorrow -

UK to mismanage quarter of a million tonnes of plastic waste this year

UK to mismanage quarter of a million tonnes of plastic waste this year -

How can visionary design save the world?

How can visionary design save the world? -

Interview with Thanawat Trivisvavet, Managing Director of CKPower

Interview with Thanawat Trivisvavet, Managing Director of CKPower -

Elsewedy Electric - Powering progress

Elsewedy Electric - Powering progress -

Thailand’s CKPower leads sustainable business model

Thailand’s CKPower leads sustainable business model -

It’s time to focus on the ‘S’ in ESG

It’s time to focus on the ‘S’ in ESG -

The seven competencies of ESG leaders

The seven competencies of ESG leaders -

Why businesses must begin their net zero journey now

Why businesses must begin their net zero journey now -

Every drop of the ocean is connected - Ocean Bottle

Every drop of the ocean is connected - Ocean Bottle