A clarion call in the fight against climate change

John E. Kaye

- Published

- Climate Change, Science, Sustainability

Climate science is no longer keeping up with the accelerating extreme impacts of climate change, but we still have to respond aggressively, decisively, and intelligently says long-time climate change researcher and former US government advisor Gary Yohe

The climate has been changing faster than progress in climate science for quite some time, but the last few years have brought this reality to the fore. The growing question as we try to move forward having seen the evidence for ourselves is simple: what do we do now?

I will offer some suggestions of how to respond by the end of this discussion, but I begin with a few examples of the increasing pace of climate change. I follow with some examples of our scientific understanding of what the future might look like in light of those changes and our ability to communicate current and future climate. I then turn to a parallel discussion of our evolving decision space with some examples of how we might cope with a new and likely persistent reality – what used to be high consequence climate events with very low likelihoods in our understanding of climate risk are rapidly becoming locally catastrophic events for which likelihoods are now fundamentally unknown.

Let’s begin with the increasingly evident finding that the pace of the climate change is accelerating. Here I briefly describe three notable and detected changes that all have global reach for which fingerprinting climate change in their attribution is increasingly challenging.

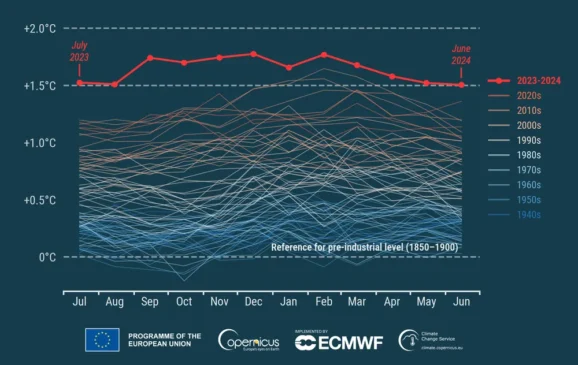

Record recent heat

The twelve months between June of 2023 and June of 2024 (see fig: 1) were all the hottest seen on Earth since the turn of the last century. It is important to note that they were not just a little bit hotter than the previous records set in 2022. They represent unprecedentedly large departures from a transient norm that had been suggested by our experiences over the last decade.

Science has advanced a large number of possible explanations for these anomalies; they include: a volcanic eruption in Tonga; a dramatic reduction in sulphur emissions caused by new shipping regulations’ coming into force; an historic maximum in periodic solar activity; and a record shifting of temperature maxima in the El Niño/La Niña (ENSO) cycle. Even casual comparison down that list shows that these explanations are importantly different in character:

- The volcanic eruption in Tonga is highly unlikely to contribute to long-term increases in temperature since it is an isolated natural event whose effects will depreciate over time.

- Reductions in sulphur emissions from any source can lead to less cooling, but this contribution to warming is the product of a “one-off” policy event that will not be replicated any time soon.

- Solar activity has a long-standing 11-year periodicity with no causal connection to what is happening on our planet.

- Scientific assessments have high confidence in the existence of a persistent causal link between human-induced warming and changes in ENSO variability.

In short, of the four possible drivers of recent extreme temperatures, only changing ENSO patterns hold the potential for contributing persistently to future extreme temperature episodes AND so only they are demonstrably sensitive to global efforts to mitigate emissions.

These last two points show why it is critical to understand the degree to which the recent abnormal El Niño was responsible for the contemporaneous record global temperatures. Only then can we assess whether the 2023-24 temperatures were an aberration or a harbinger of things to come.

Data: ERA5 1940-2024. Reference period: 1850-1900 (credit: C3S/ECMWF)

Thousand-year events and tipping points

Let’s move on to look at “the apparent increase in the frequency of one-in-a-hundred (or thousand) year events”. Likelihood statements such as these are difficult to understand, but they nonetheless communicate feelings about the magnitude of specific events in a specific locations. To assess scientific confidence in those feelings, though, it is important to recognise they are based on past experiences.

You need only look at events in September of 2024 to see a problem with assigning high confidence to backward-looking constructions such as 1,000 year events. You cannot find, in the historical data, any event as extreme as what Hurricane Helene delivered to western North Carolina. In Ashville, the previous record from a “one-in-100-year” flood brought river levels in the downtown area approximately 28 feet above past averages. This year’s storm doubled that record by adding another 28 feet to that historic mark. No wonder they called it “Biblical”.

Nor can you find an historic precedent for the contemporaneous expansive flooding across five European countries in late September. And nowhere can you see rapidly repeating maximally extreme events like what happened along the western coast of Florida. Recall that Hurricane Milton brought never-before experienced extreme flooding when it made landfall just south of Tampa less than two weeks after a glancing blow from Hurricane Helene had produced a then unprecedented “one-in-a-1000-year” flooding event.

Then we have tipping points, like the potential collapse of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS). A 2013 report from the United States National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine shows us that the potential loss of land-based ice in Antarctica has been a concern for those involved in projecting future global sea level rise (SLR) for more than a decade. As reflected in the sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC AR6), though, many researchers still argue that its contribution will be gradual over the next several centuries. They do this by ignoring paleoclimatic history and recent observations of polar ice behaviour that have combined to make it essential that we question that relatively benign future. This new work suggests that Antarctic glaciers could be crossing tipping points if temperatures rose above poorly known thresholds sometime before the middle of this century. Were that to happen, the dynamics of ice loss could rapidly metamorphise into a new state that would rapidly produce larger and more impactful global contributions to rising seas.

I have recently participated with colleagues Ben Santer, Richard Alley, Henry Jacoby and Richard Richels in submitting a paper to Climatic Change where we include a more troubling claim: missing fundamental physics and inadequate coupling of ice sheet, ocean, and atmospheric systems in models that seek to explain climate events south of latitude 60S mean that current models are unfit for the purpose of credibly projecting future dynamics on and around the Antarctica – in part because not a single current model can replicate the planet’s most immediate past during which grounded Antarctic ice was stable for nearly 9,000 years until it suddenly became demonstrably unstable around the turn of this century.

In short, the consequences of now not implausible extremes could become unimaginably catastrophic while their likelihoods can no longer be credibly estimated.

What to do now?

We have three ways to respond to climate risks: abate, adapt, or suffer. The third option recognises that we cannot avoid the residual damage and harm that will remain even if we do our best with the first two. And what do our best efforts look like? How we should now approach those response decisions while we struggle with these new scientific challenges?

Mitigation

The effects of these challenges on planning for mitigation are perhaps the easier to describe. Uncertainty is never a reason for inaction in abatement. It is, instead, a reason to feel more urgency in undertaking immediate steps to support more robust mitigation by dramatically larger public and private international research designed explicitly to inform future policy iterations by fostering rigorous and timely “fingerprinting” of the sources of specific extreme events, the sources of aggregate temperature anomalies, and the timing of crossing tipping point thresholds.

Adaptive responses

The story for adaptation is more complicated. To see why, consider the emerging difficulty in producing credible SLR projections in the context of the tipping point discussion above. SLR futures unfold on decadal to century-long timescales while adaptation responses in coastal protection need to begin as soon as possible. In this regard, society faces two potential sources of regret. The first recognises that public and/or private responses may turn out to be too-little-too late so that lives and assets would be unnecessarily jeopardised. Alternately, substantial protection projects could also turn out to be too-much-too-early so that scarce resources would be expended before they were actually needed.

Even if investments in coastal adaption are timed perfectly, they can be enormously expensive. The US Army Corps of Engineers has been working since 2020 with several US cities facing considerable risk from SLR. New York City, for example, is entertaining protection plans estimated to cost $53bn. The initial phase of the plan for protecting the San Francisco waterfront is priced at $13bn, and the Texas Tribune reported in 2023 that a dike designed to shield the Galveston and the Houston region from rising seas could cost $57bn.

The San Francisco case is particularly interesting. City planners asked the Army Corps to address both sources of regret when they commissioned a feasibility study for protecting their coastline from the Golden State Bridge to the airport. In their work, the Corps considered seven alternative responses along three alternative SLR scenarios ranging from no action and simple flood proofing up to partial withdrawal from the coastline. Two of the scenarios reflect the IPCC AR6 range of 1 or 3-feet of SLR relative to current levels by 2100. Their third reaches 7-feet because it includes significant contributions from Antarctica even though that is a future assessed to be “extremely unlikely” in the same IPCC AR6.

Each response was designed to accommodate two planned iterative mid-course corrections – one mid-century and another in 2090. This allowed them to recommend acting in the first stage as if it were known with certainty that they were moving along the 3-foot scenario for most of the city coastline. For the Embarcadaro, though, the Corps recommended working under an initial assumption that the coast will be seeing the evolving threats of the 7-foot trajectory. Why? Because it is frequently cheaper to slow down an early aggressive investment pathway than it is to speed up a laggardly conservative one, especially when there is no rigorous scientific rationale for asserting that this future could be ignored.

© Felix Mizioznikov / Shutterstock.com

To conclude

It should be clear this article is not an ordinary “red flag” warning that climate change poses an existential threat to life on Earth as we know it. This warning goes much further than that.

Adding new evidence about climate change into our scientific understanding over the past decade has not reduced uncertainty. Instead, it has uncovered enormous new challenges for scientists and decision-makers. Nonetheless, our response cannot again be “Wait until this all gets sorted out,” because we don’t have time for that. This warning is therefore a clarion call for more urgency in accelerating our abatement of greenhouse gas emissions and fundamentally changing our development patterns. It also urgently calls for creating, analysing, and implementing new adaptation decision strategies built around hedging and iterative risk management.

These brief examples of science in lagging transition support a call for enormous and secure financial support for public and private initiatives to spawn and sustain collaborative global research efforts in areas from pure science (basic physics in the global south, e.g.) to decision science. This is exactly what happened two decades ago when society demanded a coherent, consistent, and coordinated effort by scientists from around the world to improve demonstrably our abilities to attribute and fingerprint a wide of observed impacts of a warming climate across a wide range of natural and societal systems. We have to do that, again.

Finally, this is a clarion call to attract, motivate, and support a large cohort of new scientists who will tackle these new challenges because, right now, human capital is as scarce as financial capital when it comes to doing this essential work.

Time is so short that these tasks must be accepted rapidly across governmental, non-governmental and a variety of private entities who operate under public initiatives like the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and the World Climate Research Program. As well, other synthesising organisations like the G7, the G21 or the World Economic Forum should quickly find a way to mobilise themselves and their influential members.

Gary Yohe retired from teaching in 2019, ending a 42-year tenure on the faculty at Wesleyan University as the Huffington Foundation Professor of Economics and Environmental Studies. He has been researching and trying to communicate climate change, climate risk, and climate policy since 1981. From the mid 1990s through 2018, he served as a senior member of the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change where he shared the 2007 Nobel Peace Prize with Al Gore. He was Vice Chair of the 2014 Third National Climate Assessment for the Obama Administration and a charter member of the New York (City) Panel on Climate Change for Michael Bloomberg. He continues serve as Co-editor-in-Chief, along with Michael Oppenheimer, of the journal Climatic Change.

Main image: Catastrophic forest fires are becoming the norm around the world

RECENT ARTICLES

-

WPSL targets £16m-plus in global sponsorship drive with five-year SGI partnership

WPSL targets £16m-plus in global sponsorship drive with five-year SGI partnership -

Dubai office values reportedly double to AED 13.1bn amid supply shortfall

Dubai office values reportedly double to AED 13.1bn amid supply shortfall -

€60m Lisbon golf-resort scheme tests depth of Portugal’s upper-tier housing demand

€60m Lisbon golf-resort scheme tests depth of Portugal’s upper-tier housing demand -

2026 Winter Olympics close in Verona as Norway dominates medal table

2026 Winter Olympics close in Verona as Norway dominates medal table -

Europe’s leading defence powers launch joint drone and autonomous systems programme

Europe’s leading defence powers launch joint drone and autonomous systems programme -

Euro-zone business activity accelerates as manufacturing returns to expansion

Euro-zone business activity accelerates as manufacturing returns to expansion -

Deepfake celebrity ads drive new wave of investment scams

Deepfake celebrity ads drive new wave of investment scams -

WATCH: Red Bull pilot lands plane on moving freight train in aviation first

WATCH: Red Bull pilot lands plane on moving freight train in aviation first -

Europe eyes Australia-style social media crackdown for children

Europe eyes Australia-style social media crackdown for children -

These European hotels have just been named Five-Star in Forbes Travel Guide’s 2026 awards

These European hotels have just been named Five-Star in Forbes Travel Guide’s 2026 awards -

McDonald’s Valentine’s ‘McNugget Caviar’ giveaway sells out within minutes

McDonald’s Valentine’s ‘McNugget Caviar’ giveaway sells out within minutes -

Europe opens NanoIC pilot line to design the computer chips of the 2030s

Europe opens NanoIC pilot line to design the computer chips of the 2030s -

Zanzibar’s tourism boom ‘exposes new investment opportunities beyond hotels’

Zanzibar’s tourism boom ‘exposes new investment opportunities beyond hotels’ -

Gen Z set to make up 34% of global workforce by 2034, new report says

Gen Z set to make up 34% of global workforce by 2034, new report says -

The ideas and discoveries reshaping our future: Science Matters Volume 3, out now

The ideas and discoveries reshaping our future: Science Matters Volume 3, out now -

Lasers finally unlock mystery of Charles Darwin’s specimen jars

Lasers finally unlock mystery of Charles Darwin’s specimen jars -

Strong ESG records help firms take R&D global, study finds

Strong ESG records help firms take R&D global, study finds -

European Commission issues new cancer prevention guidance as EU records 2.7m cases in a year

European Commission issues new cancer prevention guidance as EU records 2.7m cases in a year -

Artemis II set to carry astronauts around the Moon for first time in 50 years

Artemis II set to carry astronauts around the Moon for first time in 50 years -

Meet the AI-powered robot that can sort, load and run your laundry on its own

Meet the AI-powered robot that can sort, load and run your laundry on its own -

Wingsuit skydivers blast through world’s tallest hotel at 124mph in Dubai stunt

Wingsuit skydivers blast through world’s tallest hotel at 124mph in Dubai stunt -

Centrum Air to launch first European route with Tashkent–Frankfurt flights

Centrum Air to launch first European route with Tashkent–Frankfurt flights -

UK organisations still falling short on GDPR compliance, benchmark report finds

UK organisations still falling short on GDPR compliance, benchmark report finds -

Stanley Johnson appears on Ugandan national television during visit highlighting wildlife and conservation ties

Stanley Johnson appears on Ugandan national television during visit highlighting wildlife and conservation ties -

Anniversary marks first civilian voyage to Antarctica 60 years ago

Anniversary marks first civilian voyage to Antarctica 60 years ago