The renewables transition: do we have the energy?

John E. Kaye

- Published

- Home, Sustainability

In a recent trip through rural Colombia, I stood at the waterside of the Embalse Peñol-Guatapé, one of the country’s largest hydroelectric dams. Built in the 1970s, the dam holds upwards of 100 million cubic metres of water – providing a source of clean, green, easy-to-manage power, plus a scenic spot for pleasure boating. But it has its downsides, too. The construction of the dam was highly controversial and required the complete demolition of the former town of El Peñol and a good chunk of its neighbour Guatapé, while leaving many local farmers homeless.

The world has woken up to the need for a transition away from fossil fuels, replacing them with renewable energy sources. However, as the dam at Guatapé shows, introducing new energy sources brings its own problems. Is the world ready and willing to overcome them?

Gearing up for action

In recent years, a steady stream of reports, warnings and announcements from international organisations has kept the issue of climate change at the forefront of public consciousness. In October 2018, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) made waves by publishing a report on the dire consequences of inaction when it comes to weaning ourselves of oil, coal and natural gas. Then, in December, the COP24, a UN climate conference that took place in Katowice, Poland, saw delegates from countries around the world commit to new rules on fossil fuel reduction.

Burning fossil fuels to generate heat, electricity and transportation is a major source of carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas which contributes to the heating of the planet, so replacing them with alternatives is paramount. As it stands, humanity already has numerous tools for generating energy by “green” means – and the growth in recent years of wind and solar electricity generation is well publicised. Nevertheless, coal, oil and natural gas still contribute around 85% of global energy, while solar and wind make less than 2% combined.

Hydroelectricity is by far the most common source of renewable energy, contributing close to 7% of the world’s energy (the rest comes from nuclear and a handful of other renewables). However, as with the example above, building traditional mega-dams is increasingly falling out of favour due to their own environmental and social drawbacks. A transition to renewable energies in order to avoid major damage to the environment will be essential – yet navigating the obstacles will be a real challenge.

Major obstacles

“Governments need to develop policies which provide clear, long-term signals,” says Heymi Bahar, a renewables energy analyst at the International Energy Agency (IEA), an intergovernmental organisation. For Mr Bahar, the onus is on governments to really kick-start the process of transitioning to renewable sources – leave this

purely down to the private sector and utilities

will not be enough.

The transition to renewables will be a complex process with many different factors at play, but

Mr Bahar outlines the three major barriers the IEA has identified in making the transition. First, there is policy and regulatory uncertainty. Second, there are multiple infrastructure challenges. And, thirdly, there are issues around financing. Let’s look at each of these in turn…

Diego Peña García is developing renewable energy projects in the country for the Colombian firm Rymel SAS, and explains: “The challenges are many, and huge.” Despite the country’s abundant wind and solar potential, trying to introduce new energy sources is held up by a regulatory backdrop which simply can’t accommodate the new energy sources. New laws need to be drafted to allow for the less predictable ways wind and solar generate electricity and to regulate how this should be paid for.

Mr Bahar concurs: “For renewables businesses, there is so much policy uncertainty.” And this often makes it difficult to get new installations off the ground. In many places there is no clear framework with targets that set out how much energy must come from renewable sources, nor fines for failure. ™

There is also a lack of clear licencing processes in many countries, not to mention continued fossil fuel subsidies at the expense of renewables.

The second barrier is to do with physical and technical challenges. It has long been a criticism of wind and solar that they cannot produce electricity when the wind doesn’t blow and the sun doesn’t shine (although alternative renewables like geothermal and tidal aren’t so affected by this intermittency issue). But, perhaps, as much of a challenge is finding ways to integrate these new energy sources into a grid designed for the more easily controlled coal and gas. Indeed, on especially sunny and windy days, some countries have faced havoc caused by surges in electricity in their national grids.

Mr Bahar again highlights that as much as anything, the solution here will be smarter grid integration; infrastructure will need to be developed that can balance this kind of variable power.

The third obstacle is the issue of financing. In many countries, governments set up “power purchase agreements” (PPAs), which essentially guarantees the power generator an agreed price for its energy for a certain number of years: you invest £40m in a solar farm, I’ll agree to pay you £0.10 per kw/h for the next 20 years. But again, these financing options are often not set up for renewables.

When a utility builds a coal plant for instance, it can be confident of the amount of electricity it will generate over time since it can control how much coal it buys – and this means its profit forecasting can be pretty accurate. On the other hand, renewables, businesses are working with a less dependable source, and so value longer PPAs, which mean they can be sure they will recoup their costs.

In the example of Colombia, Mr Peña García explains that a typical PPA will only offer a guaranteed price for five years to the supplier of any energy source – be that coal, gas or hydro (although it has recently been extended to 12 years for renewables). Because of the fluctuating nature of the electricity market, these short-term PPAs make it less certain a profit will be made on those shorter-term deals. And this all means that investors are less confident about investing in massive wind or solar farms.

Can these challenges be overcome?

If a transition to renewables is going to happen, it is going to require co-ordination between local and national government, citizens, intergovernmental organisations, new renewables businesses, researchers and the contribution of existing energy providers, too. How will this all work out?

“We do see a future for oil and gas in the decades to come,” says Sally Donaldson, spokesperson for Shell, one of the six major global energy businesses. However, while Shell continues to see a future for fossil fuels, the business is increasingly investing in its New Energies business – to the tune of around

£2bn per year.

Shell’s New Energies includes investments in wind farms and biofuels, and the company has also begun installing electric vehicle charging points at some of its UK petrol stations, too. The company has released its own scenario models looking at how this kind of transition to a renewables-based future would happen over time, demonstrating how similar businesses would change in conjunction with governments and other factors.

The IEA’s Mr Bahar believes a transition to renewables will not happen without the contribution of the established producers: “Traditional fossil fuel providers are transforming themselves into more general energy companies… They realise renewables are the future and they are changing their portfolios.”

At the same time, he points to a slew of innovative companies tackling the issue through innovation – from new batteries for storing energy via intermittent renewables to companies that help consumers manage their electricity usage better, and smarter tech that manages payment over a decentralised grid (see Innovation Off the Grid, page 56).

If the barriers to implementing renewables can be overcome, there is clearly enormous amounts of innovation going into alternatives to fossil fuels.

The question is whether these barriers will be addressed or not.

A law of physics states that energy can neither be created nor destroyed – it can only be transformed

or transferred from one form into another. Humanity’s demand for energy to provide heat, electricity and transport will only continue to grow as the global population keeps expanding – but where we choose to transform or transfer it from is up to us.

For more energy news, follow The European

Sign up to The European Newsletter

RECENT ARTICLES

-

Mycelium breakthrough shows there’s mush-room to grow in greener manufacturing

Mycelium breakthrough shows there’s mush-room to grow in greener manufacturing -

Oxford to host new annual youth climate summit on UN World Environment Day

Oxford to host new annual youth climate summit on UN World Environment Day -

Exclusive: Global United Nations delegates meet in London as GEDU sets out new cross-network sustainability plan

Exclusive: Global United Nations delegates meet in London as GEDU sets out new cross-network sustainability plan -

Fast fashion brands ‘greenwash’ shoppers with guilt-easing claims, study warns

Fast fashion brands ‘greenwash’ shoppers with guilt-easing claims, study warns -

Private sector set to overtake government as main driver of corporate sustainability in 2026, report suggests

Private sector set to overtake government as main driver of corporate sustainability in 2026, report suggests -

Sir Trevor McDonald honoured at UWI London Benefit Dinner celebrating Caribbean achievement

Sir Trevor McDonald honoured at UWI London Benefit Dinner celebrating Caribbean achievement -

Historic motorsport confronts its energy future

Historic motorsport confronts its energy future -

Protecting the world’s wild places: Dr Catherine Barnard on how local partnerships drive global conservation

Protecting the world’s wild places: Dr Catherine Barnard on how local partnerships drive global conservation -

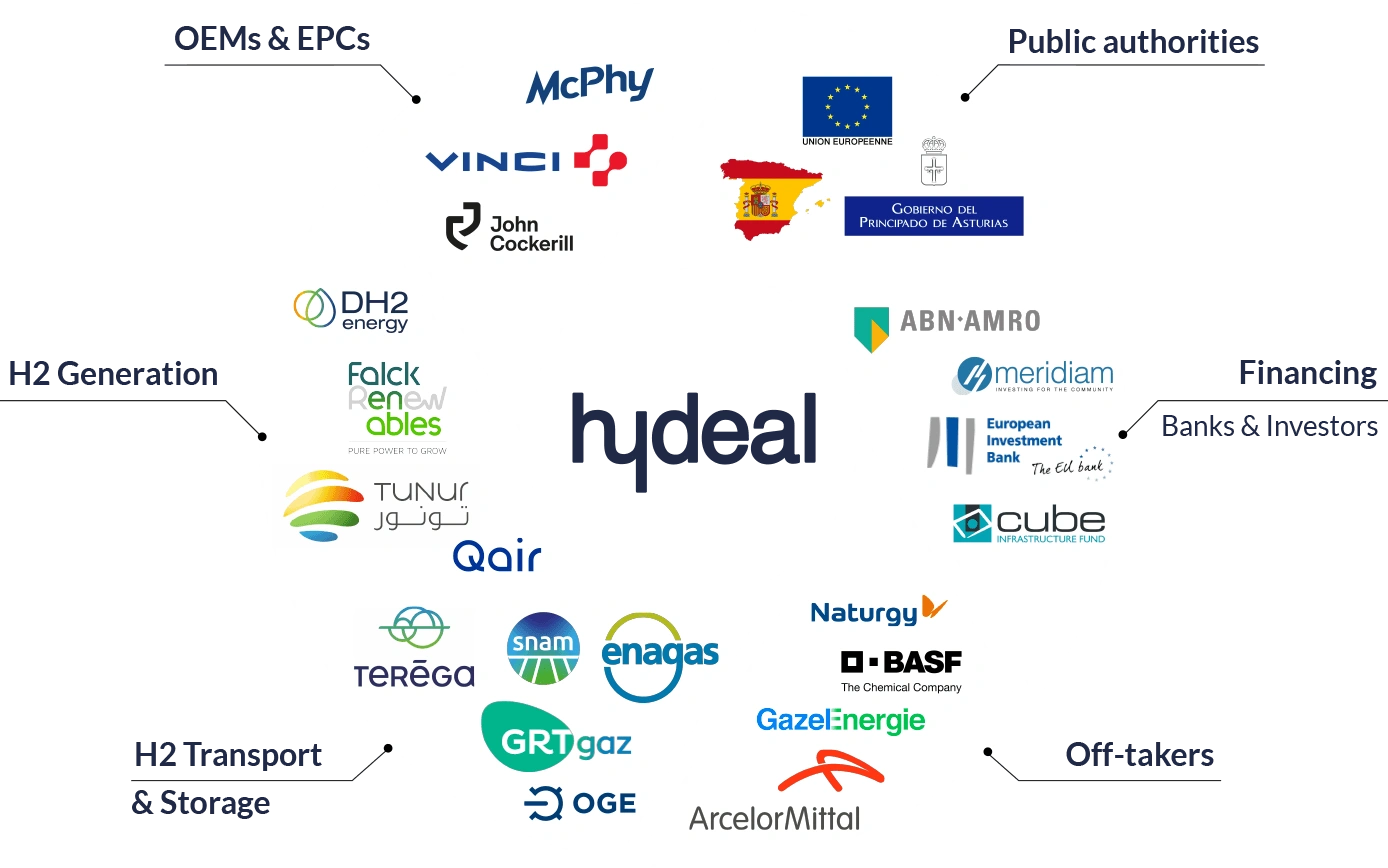

Europe’s HyDeal eyes Africa for low-cost hydrogen link to Europe

Europe’s HyDeal eyes Africa for low-cost hydrogen link to Europe -

Fabric of change

Fabric of change -

Courage in an uncertain world: how fashion builds resilience now

Courage in an uncertain world: how fashion builds resilience now -

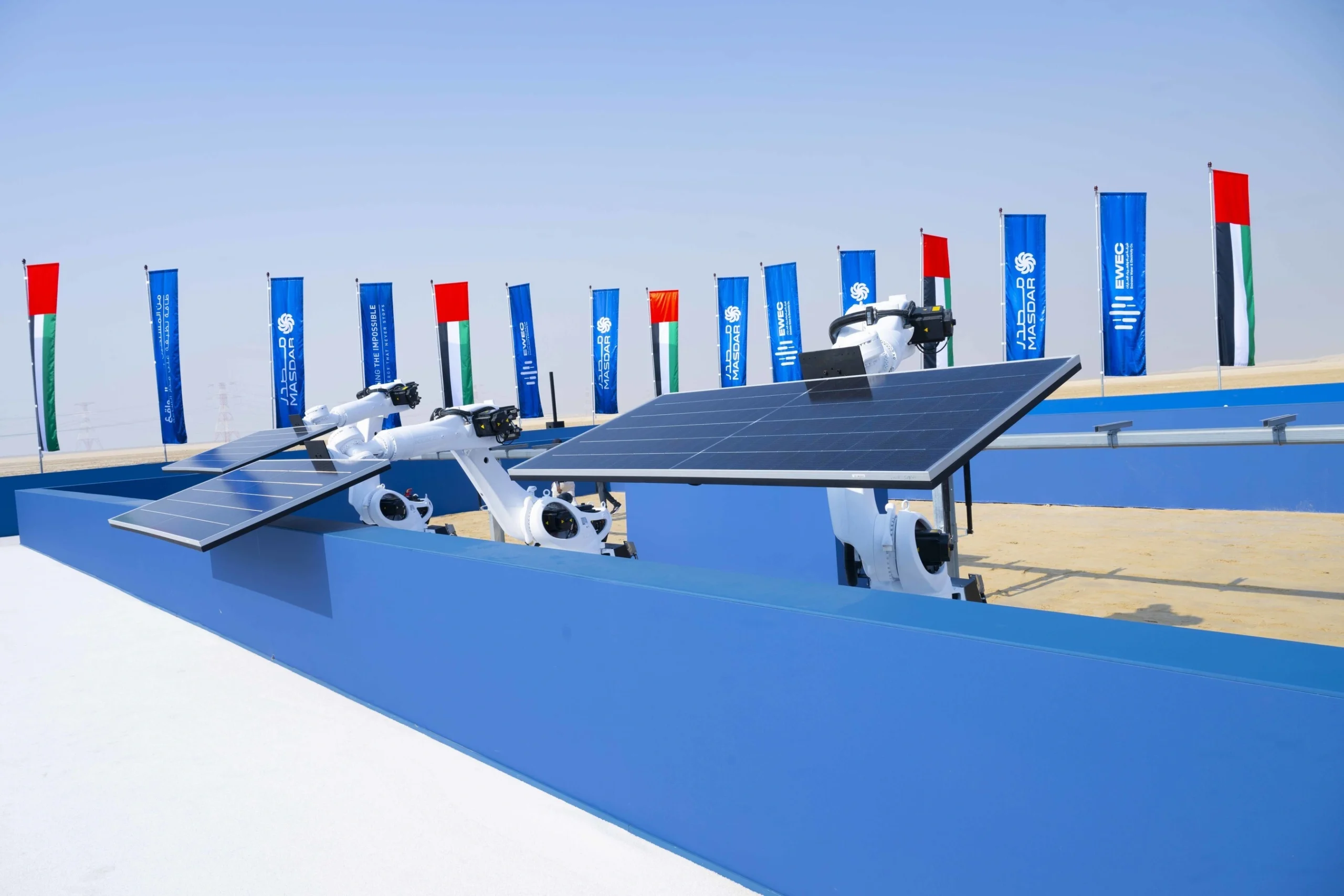

UAE breaks ground on world’s first 24-hour renewable power plant

UAE breaks ground on world’s first 24-hour renewable power plant -

China’s Yancheng sets a global benchmark for conservation and climate action

China’s Yancheng sets a global benchmark for conservation and climate action -

Inside Iceland’s green biotechnology revolution

Inside Iceland’s green biotechnology revolution -

Global development banks agree new priorities on finance, water security and private capital ahead of COP30

Global development banks agree new priorities on finance, water security and private capital ahead of COP30 -

UK organisations show rising net zero ambition despite financial pressures, new survey finds

UK organisations show rising net zero ambition despite financial pressures, new survey finds -

Gulf ESG efforts fail to link profit with sustainability, study shows

Gulf ESG efforts fail to link profit with sustainability, study shows -

Redress and UN network call for fashion industry to meet sustainability goals

Redress and UN network call for fashion industry to meet sustainability goals -

World Coastal Forum leaders warn of accelerating global ecosystem collapse

World Coastal Forum leaders warn of accelerating global ecosystem collapse -

Miliband: 'Great British Energy will be self-financing by 2030'

Miliband: 'Great British Energy will be self-financing by 2030' -

New ranking measures how Europe’s biggest retailers report on sustainability

New ranking measures how Europe’s biggest retailers report on sustainability -

Music faces a bum note without elephant dung, new research warns

Music faces a bum note without elephant dung, new research warns -

Scientists are racing to protect sea coral with robots and AI as heatwaves devastate reefs

Scientists are racing to protect sea coral with robots and AI as heatwaves devastate reefs -

Munich unveils new hydrogen lab as Europe steps up green energy race

Munich unveils new hydrogen lab as Europe steps up green energy race -

Seaweed and wind turbines: the unlikely climate double act making waves in the North Sea

Seaweed and wind turbines: the unlikely climate double act making waves in the North Sea