Building the materials of tomorrow one atom at a time: fiction or reality?

- Published

- Science, Technology

Three European materials scientists, Konstantina Lambrinou of the University of Huddersfield, Nick Goossens of Empa and Matheus A. Tunes of Montanuniversität Leoben, explain how the materials that will power cleaner energy, smarter technologies and future space missions are being designed atom by atom, and why rethinking how we process even the most familiar substances matters to us all

Technological advancement in this day and age goes hand in hand with pushing boundaries in almost all industrial sectors, as we try to explore what is achievable on Earth and beyond. These boundaries are very often defined by the materials and methods we use to travel, communicate, detect and visualise, produce energy, or even cure our ailments.

The evolution of our species appears to be accompanied by an insatiable hunger to realise our increasingly ambitious goals at neck-breaking speed. To a great extent, we operate as if we were running out of time. This might actually not be entirely unfounded considering the continuous increase in world population, the rapidly declining soil health, and our mounting collective needs in energy, housing, and sustenance. This bleak reality pushes us, in a way, to improve the efficiency of the ways with which we produce energy – preferably in environmentally-friendly manners – and discover more space to live and thrive; the latter translates into our recently intensified efforts towards space exploration.

When it comes to powering interstellar travel, nuclear energy is the only viable option that our species currently possesses; serendipitously, nuclear energy is also a low-carbon energy source that can help us combat global warming by reducing greenhouse gas emissions on Earth.

The common denominator between innovative materials needed for the deployment of advanced nuclear systems (both fission and fusion) as well as for space exploration is the extreme service environments in which materials must perform reliably.

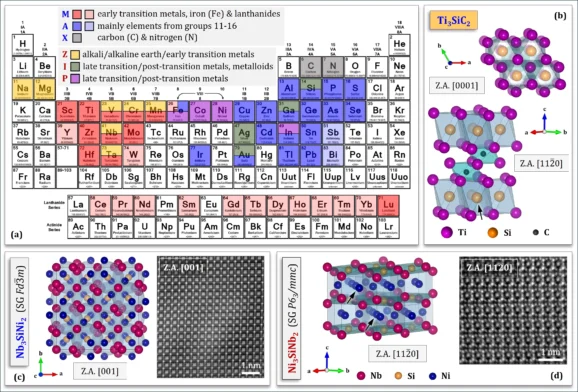

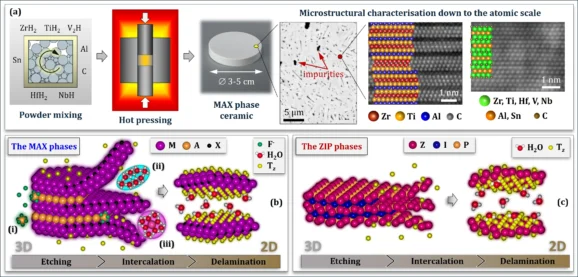

A class of materials holding great promise for applications in harsh service environments (i.e., applications demanding stability at elevated temperatures, resistance to highly corrosive media such as liquid metals and molten salts, and radiation tolerance) is the MAX phases. The MAX phases [1] are nanolaminated ternary carbides and nitrides described by the Mn+1AXn general stoichiometry, where M is an early transition metal, A is an A-group element (mainly, groups 11-16) in the periodic table, X is C or N, and n is usually equal to 1, 2 or 3 (Fig. 1a). Designing MAX phase ceramics for advanced nuclear systems aims at good compatibility with the coolant, high phase purity, strong textures, and fine-grained microstructures. High phase purity prevents failure due to differential swelling, i.e., the in-service degradation of multi-phase materials due to the fact that each phase swells differently under irradiation, causing irreconcilable stresses at grain boundaries (GBs) that lead to the formation and propagation of intergranular cracks. Texture (i.e., grain alignment along specific crystallographic directions) aims at preventing failure caused by the anisotropic swelling of the hexagonal MAX phases (space group P63/mmc), the unit cells of which expand along the c-axis and contract along the a-axis under irradiation. Figure 1b depicts two zone axes (i.e., crystallographic directions) in the crystal structure of the extensively studied Ti3SiC2 MAX phase. Grain refinement is pursued because GBs are known to act as ‘sinks’ for irradiation-induced defects in MAX phase ceramics [2]. MAX phase ceramics with high phase purity can be fabricated via powder metallurgical routes involving pressure-assisted densification of powder compacts, e.g., hot pressing (Fig. 2a).

The cornerstones of the experimental synthesis of such ceramics are (a) the judicious design of double solid solution MAX phases (i.e., solid solutions on both M- and A-sites of the MAX phase), such as (Zr,Nb)2(Al,Sn)C [3] and (Zr,Ti)2(Al,Sn)C [4], and (b) the use of early transition metal hydride powders instead of elemental powders [5]. The design of double solid solution MAX phases considers the relative atomic radii of the M & A elements to minimise crystal lattice distortions able to destabilise the MAX phase compound and yield large fractions of undesirable phases, such as binary carbides and intermetallics (IMCs). A recent trend in the design of MAX phases with exceptional radiation tolerance aims at fabricating solid solutions with high chemical complexity, such as (Zr,Ti,Hf,V,Nb)2(Al,Sn)C [6]. Chemical complexity – also explored in high-entropy alloys [7] – is held accountable for a reduced mobility of radiation-induced defects, a high density of defects ‘sinks’ or defect recombination centres, and a reduced tendency for defect accumulation that typically leads to void swelling.

Based on the above, nuclear materials design starts at the atomic scale, demonstrating the sophistication sometimes involved in materials engineering. Material synthesis is followed by microstructural characterisation across scales (Fig. 2a), starting with basic analytical techniques, such as scanning electron microscopy (SEM), energy-dispersive/wavelength-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS/WDS), electron probe microanalysis (EPMA), and electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD), and proceeding to high-resolution analytical techniques, such as high-angle annular dark-field (HAADF) scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM).

Apart from the tested ability of the MAX phases to resist degradation in contact with liquid metal coolants (used in fission/fusion and concentrated solar power) [8,9] and under irradiation [10], their crystal structure nanolamination permits the synthesis of chemically tailored 2D derivatives, known as MXenes, via the chemical etching of the A-element (usually, Al). As will be explained in the next section by Nick Goossens, the post-processing of MXenes allows for surface modification, (nano)particle decoration, and grafting of organic molecules, turning them compatible with polymers to create functional nanocomposites. Their chemical versatility and inherent capacity for deliberate atomic ordering, both in-plane and out-of-plane, makes MXenes suitable for diverse niche applications in supercapacitors, batteries, electromagnetic interference (EMI) shielding, environmental applications such as water desalination/purification, catalysis, sensors, energy storage devices, and biomedical applications [11].

Obviously, the materials that will help us shape tomorrow and assist us in bold missions, including space exploration, are not limited to chemically complex MAX phase ceramics but include widely used metallic materials such as aluminium alloys. Matheus A. Tunes will explain why reinventing traditional metallurgical processes to fabricate judiciously modified versions of well-known materials is mandatory to secure the next-generation structural materials needed for our upcoming adventures in deep space.

The advent of the ZIP phases family of ternary intermetallics

Konstantina Lambrinou of the University of Huddersfield introduces the structurally intricate ZIP phases and explains why their recent discovery opens the door to new properties and applications

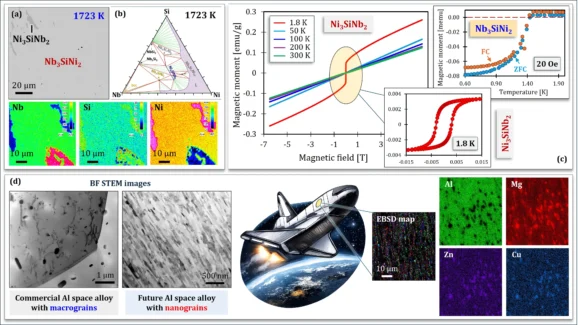

The recently discovered ZIP phases are ternary IMCs that exhibit dualistic atomic ordering, i.e., they form two structural variants: one with the face-centred cubic (fcc) structure (space group, SG, Fdm) and one with the hexagonal structure (SG P63/mmc). Konstantina Lambrinou, Nick Goossens and Matheus A. Tunes are three members of the team of scientists involved in the discovery of the ZIP phases [12] and the pioneering synthesis of quasi pure phase ZIP phase materials in the Nb-Si-Ni ternary system by means of reactive hot pressing (see Fig. 4a; sample sintered at 1723 K). ZIP phase synthesis in the Nb-Si-Ni system was guided by CALPHAD phase equilibria calculations (Fig. 4b shows the 1723 K isotherm) facilitated by the earlier thermodynamic assessment of this system [13-14]. ZIP phases were also synthesised in the Nb-Si-Co, V-Si-Ni, Ta-Si-Ni and Nb-Si-Fe systems, but the produced materials contained appreciable amounts of secondary phases mainly due to the unavailability of equilibrium phase diagrams needed to guide the synthesis efforts.

As phase purity is a stepping stone to the determination of properties, the opportunities arising from the discovery of the ZIP phases cannot be accurately predicted at present. A tentative depiction of the largely unexplored compositional landscape of the ZIP phases is shown in Fig. 1a, in combination with the fairly well-explored compositional landscape of the MAX phases. As shown in Fig. 1a, the fcc variants of the ZIP phases are made of Z-elements in groups 1-2 & 5-7; I-elements in groups 11 & 13-14; and P-elements in groups 8-10 & 13. On the other hand, the hexagonal MAX phases (SG P63/mmc) comprise M early transition metals; A elements mainly from groups 13-15; whilst X is C or N. The ZIP phases are characterised by a remarkable structural complexity; for example, the unit cell of the fcc Nb3SiNi2 has 96 atoms (Fig. 1c), whilst the unit cell of the hexagonal Ni3SiNb2 has 12 atoms (Fig. 1d); by contrast, the unit cell of the hexagonal Ti3SiC2 MAX phase has only 6 atoms (Fig. 1b).

Early investigations of the ZIP phases showed that they possess properties atypical of the MAX phases due to the inclusion of elements that are not MAX phase-formers (i.e., late transition metals; alkali and alkaline earth metals; see Fig. 1a). For example, magnetic properties were measured in Nb3SiNi2 and Ni3SiNb2 (Fig. 4c), revealing ferromagnetic-to-paramagnetic transitions at Curie temperatures, TC, of ~22 K and ~14 K, respectively, whereas superconductivity was discovered in Nb3SiNi2 below 1.4 K (Fig. 4c) [12]. By contrast, only a handful of studies have measured magnetic properties in experimentally synthesised MAX phases, i.e., the (Cr0.75,Mn0.25)2GeC MAX phase solid solution [15]; rare-earth-containing i-MAX phase solid solutions (i.e., MAX phase compounds with in-plane ordered M-elements) of the (Mo2/3, RE1/3)2AlC stoichiometry, where RE = Ce, Pr, Nd, Sm, Gd, Tb, Dy, Ho, Er, Tm, and Lu [16,17]; and (Ti1-x,Fex)3AlC2 MAX phase solid solutions, where x = 0, 0.025, 0.05, and 0.075 [18]. On the other hand, superconductivity has only ever been reported for the Lu2SnC ternary MAX phase compound [19].

Lastly, the striking structural similarity between the hexagonal ZIP phase variants and the hexagonal MAX phases (both SG P63/mmc), including their inherent nanolamination (see Fig. 1b & 1d), suggests that the synthesis of 2D derivatives of the ZIP phases via chemical etching (see Fig. 2c) might be plausible, even though it has not yet been proven experimentally. Assuming that the new range of properties achieved by the ZIP phases (e.g., magnetic properties, superconductivity) is transferable to their 2D derivatives, one can rightfully expect the advent of a next generation of nano-tailored 2D materials for use in flexible and wearable electronics, batteries, quantum computing, highly sensitive sensors, biomedical applications such as smart drug delivery, etc.

Customised 2D materials and their functional nanocomposites

Nick Goossens of Empa delves into the fascinating world of MXenes and the opportunities arising from their use to make nanocomposites with directionally tailored properties

The crystal structure nanolamination of the MAX phases enables their exfoliation into 2D early transition metal carbides and/or nitrides known as ‘MXenes’ [20], drawing the analogy with graphene as the 2D derivative of graphite. MAX phase exfoliation requires the selective breaking of the M-A bonds (typically by chemically etching the A-elements; Fig. 2b), followed by the delamination of the weakened structure. The latter may be intensified by large ionic species (e.g., solvated Li+/NH4+ [21]) that intercalate the etched MAX phase and apply a mechanical force to separate the individual MXene layers. The freshly formed MXene surface contains highly reactive dangling bonds that immediately react with nearby electronegative species to stabilise the surface. Although the surface chemistry initially depends on the etching environment, MXene post-processing allows for intentional surface modification, (nano)particle decoration, and molecular grafting. MXenes hold great promise in diverse energy-related (e.g., batteries and supercapacitors), environmental (e.g., water desalination and purification), catalysis, sensing, and biomedical applications [22,23]. Customising their structure and (surface) chemistry vis-à-vis their envisaged application is key as (electro)chemical properties are largely determined by the transition metal(s). Therefore, innovative MXene research focuses on the controlled incorporation of less conventional M-elements (e.g., Zr [24], Mo [25], and W [26]) and the intentional formation of solid solution MXenes to unlock superior functional performance [27].

These quests are inherently limited by the (in)ability to produce suitable atomically layered precursor materials with high phase purity, such as chemically complex [28-30] and ordered [31] MAX phase solid solutions or nanolaminates with a non-MAX phase stoichiometry (e.g., Zr3Al3C5) [24]. Combining many different transition elements in so-called chemically complex, entropy-enhanced or high-entropy compounds is a hot topic in the ongoing research and development of new MAX phases and their derived MXenes with complete customisability of structure, composition, and properties.

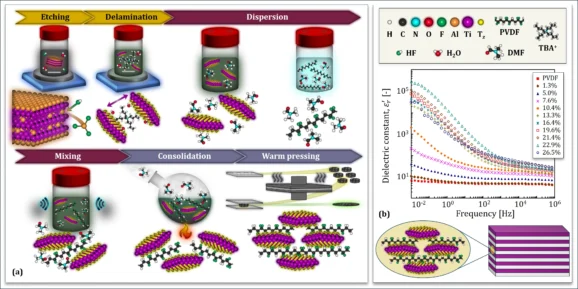

The tuneable MXene surface chemistry offers an additional degree of freedom for application-oriented materials engineering through its compatibilization with polymers. Dispersing MXenes in polymers produces functional nanocomposites that combine the functional performance of the MXene with the mechanical rigidity of the polymer, enabling structural applications. Figure 3a illustrates schematically the processing of a Ti3C2Tz MXene (where Tz represents reactive surface terminations) in a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) matrix: the etched Ti3AlC2 precursor MAX phase is first delaminated by intercalating its layers with large tetrabutylammonium (TBA) cations and consequently dispersed in dimethylformamide (DMF). Since PVDF dissolves in DMF, intricate molecular mixing of MXene sheets and PVDF chains happens automatically. The MXene/PVDF mixture is then consolidated by casting it in a specifically shaped mould whilst applying heat and pressure, producing a nanocomposite with direction-dependent properties, owing to the controllable orientation of the MXene platelets.

For example, planar alignment of the electrically conductive MXenes renders the nanocomposite electrically conductive in-plane and electrically insulating out-of-plane.

This makes Ti3C2Tz/PVDF nanocomposites useful as low-frequency nanodielectrics with improved energy density [32], as proven by the high dielectric constants shown in Fig. 3b; high dielectric constants are able to suppress out-of-plane loss currents and dielectric breakdown even under large applied electric fields (up to 10 MV/m),

something that is not achievable by conventional percolation-based particulate nanocomposites.

Reinventing aluminium for Europe’s future in space

Matheus A. Tunes of Montanuniversität Leoben explains why space exploration will ask us to revisit the metallurgy of a metal we take for granted in our everyday lives: aluminium

Aluminium (Al) alloys have shaped the history of spaceflight [33]. Their low density, high specific strength, and excellent manufacturability have made them indispensable for satellites, launch vehicles, and spacecraft structures. As space exploration enters a new phase – defined by long-duration missions, deep-space operations, and plans for extraterrestrial settlement – this well-established class of materials faces challenges of an entirely new magnitude. Chief among them is the sustained exposure to the Sun’s energetic particle radiation, acting in concert with thermal cycling, vacuum, and mechanical damage due to impact with micrometeoroids and space debris. Meeting these conditions requires not incremental optimisation, but a fundamental rethinking of Al metallurgy [33]. Cosmic radiation tolerance has emerged as a decisive bottleneck [34,35].

Conventional aerospace Al alloys derive their strength from nanometric precipitates that are thermodynamically metastable. Under energetic particle irradiation, these strengthening phases dissolve at very low displacement damage doses, leading to rapid deterioration of mechanical performance [36]. At the same time, irradiation induces the accumulation of lattice defects, such as dislocation loops and voids, which further degrade structural integrity. These mechanisms severely limit the applicability of many commercial alloys for missions beyond Earth’s protective magnetosphere. Recent European-led research at the Austrian [X-MAT] Laboratory for Metallurgy in Extreme Environments demonstrates that these limitations are not intrinsic to Al itself, but rather to traditional alloy design strategies [33]. By integrating concepts from nuclear materials science, advanced processing and microstructural engineering, Al alloys can be redesigned to tolerate radiation levels far exceeding those expected in space environments [34,37].

Central to this progress is the recognition that radiation resistance must be engineered at multiple length scales: from atomic-scale phase stability to mesoscopic grain structures that actively suppress defect accumulation [33,37]. One promising direction lies in the development of chemically complex strengthening phases that remain stable under irradiation, combined with refined grain structures (see Fig. 4d) acting as effective ‘sinks’ for radiation-induced defects [33,34]. Experimental studies using in situ ion irradiation and advanced electron microscopy have shown that such microstructures can suppress the formation of deleterious defects, retaining mechanical performance under extreme conditions. Importantly, these advances preserve aluminium’s inherent advantages: low weight, high formability, and compatibility with established industrial processing routes.

Austria has emerged as a key European hub in the new space race, especially considering its strong and advanced industrial portfolio in the fields of metallurgy and materials science. Research conducted at Austrian universities and research centres – embedded in strong international collaborations with laboratories in Europe, the United States, and beyond – has positioned Europe at the forefront of radiation-resistant Al alloy development [33]. This work combines alloy design, state-of-the-art characterisation, and irradiation testing to deliver insights that are globally recognised and increasingly relevant for future space systems. Such leadership demonstrates that Europe possesses not only the scientific expertise, but also the infrastructure and industrial ecosystem needed to shape next-generation space materials.

The strategic implications extend well beyond materials science. Aluminium alloys remain uniquely suited for sustainable space exploration [33]. They can be recyclable, economically viable, and compatible with additive manufacturing – an enabling technology for in-space manufacturing and repair. As space activities shift from short missions to long-term presence, materials that combine radiation tolerance with manufacturability and lifecycle sustainability will be indispensable.

Despite these strengths, Europe risks falling behind if investment does not keep pace with ambition. Space materials development is inherently capital-intensive, requiring particle irradiation facilities, advanced microscopy, and long-term research programmes. While other global actors are rapidly expanding their space capabilities [33], Europe must ensure that funding, infrastructure, and coordinated strategy support its scientific leadership. Investment in space materials is not merely a scientific endeavour; it is a strategic necessity underpinning autonomy, security, and economic competitiveness.

The future of space exploration will not be enabled by abandoning familiar materials, but by re-engineering them for environments that differ greatly from those for which they were originally conceived. Aluminium alloys – reinvented through advanced metallurgy – are poised to remain a cornerstone of spaceflight. Europe has the expertise to lead this transformation. Sustained commitment and investment will determine whether it also secures its place among the leaders of the next space age.

References

[1] N. Goossens, B. Tunca, T. Lapauw, K. Lambrinou, J. Vleugels, MAX phases, structure, processing, and properties, Encyclopedia of Materials: Technical Ceramics and Glasses 2 (2021) 182-199

[2] D.J. Tallman, L. He, J. Gan, E.N. Caspi, E.N. Hoffman, M.W. Barsoum, Effects of neutron irradiation of Ti3SiC2 and Ti3AlC2 in the 120-1085°C temperature range, Journal of Nuclear Materials 484 (2017) 120-134

[3] T. Lapauw, B. Tunca, D. Potashnikov, A. Pesach, O. Ozeri, J. Vleugels, K. Lambrinou, The double solid solution

(Zr,Nb)2(Al,Sn)C MAX phase: a steric stability approach, Scientific Reports 8 (2018) 12801

[4] B. Tunca, T. Lapauw, R. Delville, D.R. Neuville, L. Hennet, D. Thiaudière, T. Ouisse, J. Hadermann, J. Vleugels, K. Lambrinou, Synthesis and characterisation of double solid solution (Zr,Ti)2(Al,Sn)C MAX phase ceramics, Inorganic Chemistry 58 (2019) 6669-6683

[5] N. Goossens, T. Lapauw, K. Lambrinou, J. Vleugels, Synthesis of MAX phase-based ceramics from early transition metal hydride powders, Journal of the European Ceramic Society 42 (2022) 7389-7402

[6] B. Tunca, S. Huang, N. Goossens, K. Lambrinou, J. Vleugels, Chemically complex double solid solution MAX phase-based ceramics in the (Ti,Zr,Hf,V,Nb)-(Al,Sn)-C system, Materials Research Letters 10 (2022) 52-61

[7] C. Lu, L. Niu, N. Chen, K. Jin, T. Yang, P. Xiu, Y. Zhang, F. Gao, H. Bei, S. Shi, I.M. Robertson, W.J. Weber, L. Wang, Enhancing radiation tolerance by controlling defect mobility and migration pathways in multicomponent single-phase alloys, Nature Communications 7 (2016) 13564

[8] T. Lapauw, B. Tunca, J. Joris, A. Jianu, R. Fetzer, A. Weisenburger, J. Vleugels, K. Lambrinou, Interaction of Mn+1AXn phases with oxygen-poor, static and fast-flowing liquid lead-bismuth eutectic, Journal of Nuclear Materials 520 (2019) 258-272

[9] B. Tunca, T. Lapauw, C. Callaert, J. Hadermann, R. Delville, E.N. Caspi, M. Dahlqvist, J. Rosén, A. Marshal, K.G. Pradeep, J.M. Schneider, J. Vleugels, K. Lambrinou, Compatibility of Zr2AlC MAX phase-based ceramics with oxygen-poor, static liquid lead-bismuth eutectic, Corrosion Science 171 (2020) 108704

[10] B. Tunca, G. Greaves, J.A. Hinks, P.O.Å. Persson, J. Vleugels, K. Lambrinou, In situ He+ irradiation of the double solid solution (Ti0.5,Zr0.5)2(Al0.5,Sn0.5)C MAX phase: Defect evolution in the 350-800°C temperature range, Acta Materialia 206 (2021) 116606

[11] B. Anasori and Y. Gogotsi (Eds.), “2D metal carbides and nitrides (MXenes)”, 2019, Springer, Switzerland

[12] M.A. Tunes, S.M. Drewry, F. Schmidt, J.A. Valdez, M.M. Schneider, C.A. Kohnert, T.A. Saleh, S. Fensin, S.A. Maloy, C.G. Schön, S. Dubois, O. Tabo, A. Eyal, A. Keren, A. Pesach, G.K. Nayak, S.R.G. Christopoulos, M. Molinari, M. Hans, N. Goossens, S. Huang, J.M. Schneider, P.O.Å. Persson, J. Vleugels, K. Lambrinou, A new family of ternary intermetallic compounds with dualistic atomic ordering – The ZIP phases, Advanced Materials 2025 (2025) e08168

[13] V.O. dos Santos, H.M. Petrilli, C.G. Schön, L.T.F. Eleno, Thermodynamic modelling of the Nb-Ni-Si phase diagram based on the 1073 K isothermal section using ab initio calculations, Calphad 51 (2015) 57-66

[14] V.O. dos Santos, L.T.F. Eleno, C.G. Schön, K.W. Richter, Experimental investigation of phase equilibria in the Nb-Ni-Si refractory alloy system at 1323 K, Journal of Alloys and Compounds 842 (2020) 155373

[15] A.S. Ingason, A. Mockute, M. Dahlqvist, F. Magnus, S. Olafsson, U.B. Arnalds, B. Alling, I.A. Abrikosov, B. Hjörvarsson, P.O.Å. Persson, J. Rosén, Magnetic self-organised atomic laminate from first principles and thin film synthesis, Physical Review Letters 110 (2013) 195502

[16] H. Tong, S. Lin, Y. Huang, P. Tong, W. Song, Y. Sun, Difference in physical properties of MAX-phase compounds Cr2GaC and Cr2GaN induced by an anomalous structure change in Cr2GaN, Intermetallics 105 (2019) 39-43

[17] D. Potashnikov, E.N. Caspi, A. Pesach, Q. Tao, J. Rosén, D. Sheptyakov, H.A. Evans, C. Ritter, Z. Salman, P. Bonfa, T. Ouisse, M. Barbier, O. Rivin, A. Keren, Magnetic structure determination of high-moment rare-earth-based laminates, Physical Reviews B 104 (2021) 174440

[18] S. Sun, Y. Yu, S. Sun, Q. Wang, T. Chen, J. Chen, Y. Zhang, W. Cui, Magnetic properties and microstructures of Fe-doped

(Ti1-xFex)3AlC2 MAX phase and their MXene derivatives, Journal of Superconductivity and Novel Magnetism 34 (2021) 1477-1483

[19] S. Kuchida, T. Muranaka, K. Kawashima, K. Inoue,

M. Yoshikawa, J. Akimitsu, Superconductivity in Lu2SnC, Physica C 494 (2013) 77-79

[20] M. Naguib, M. Kurtoglu, V. Presser, J. Lu, J. Niu, M. Heon, L. Hultman, Y. Gogotsi, M.W. Barsoum, Two‐dimensional nanocrystals produced by exfoliation of Ti3AlC2, Advanced Materials 23 (2011) 4248-4253

[21] N. Goossens, K. Lambrinou, B. Tunca, V. Kotasthane, M.C. Rodríguez González, A. Bazylevska, P.O.Å. Persson, S. De Feyter, M. Radovic, F. Molina‐Lopez, J. Vleugels, Upscaled synthesis protocol for phase‐pure, colloidally stable MXenes with long shelf lives, Small Methods 2023 2300776

[22] M. Naguib, M.W. Barsoum, Y. Gogotsi, Ten years of progress in the synthesis and development of MXenes, Advanced Materials 33 (2021) 2103393

[23] Y. Gogotsi, B. Anasori, The rise of MXenes, ACS Nano 13 (2019) 8491-8494

[24] J. Zhou, X. Zha, F.Y. Chen, Q. Ye, P. Eklund, S. Du, Q. Huang, A two-dimensional zirconium carbide by selective etching of Al3C3 from nanolaminated Zr3Al3C5, Angewandte Chemie International Edition 55 (2016) 5008-5013

[25] Q. Tao, M. Dahlqvist, J. Lu, S. Kota, R. Meshkian, J. Halim, J. Palisaitis, L. Hultman, M.W. Barsoum, P.O.Å. Persson, J. Rosén, Two-dimensional Mo1.33C MXene with divacancy ordering prepared from parent 3D laminate with in-plane chemical ordering, Nature Communications 8 (2017) 14949

[26] A. Thakur, W.J. Highland, B.C. Wyatt, J. Xu, N. Chandran B. S, B. Zhang, Z.D. Hood, S.P. Adhikari, E. Oveisi, B. Pacakova, F. Vega, J. Simon, C. Fruhling, B. Reigle, M. Asadi, P.P. Michałowski, V.M. Shalaev, A. Boltasseva, T.E. Beechem, C. Liu, B. Anasori, Synthesis of a 2D tungsten MXene for electrocatalysis, Nature Synthesis 4 (2025) 888-900

[27] S.K. Nemani, B. Zhang, B.C. Wyatt, Z.D. Hood, S. Manna, R. Khaledialidusti, W. Hong, M.G. Sternberg, S.K.R.S. Sankaranarayanan, B. Anasori, High-entropy 2D carbide MXenes: TiVNbMoC3 and TiVCrMoC3, ACS Nano 15 (2021) 12815-12825

[28] B. Anasori, Y. Xie, M. Beidaghi, J. Lu, B.C. Hosler, L. Hultman, P.R.C. Kent, Y. Gogotsi, M.W. Barsoum, Two-dimensional, ordered, double transition metals carbides (MXenes), ACS Nano 9 (2015) 9507-9516

[29] N. Goossens, B. Tunca, M. Stuer, P.O.Å. Persson, J.W. Seo, S. Huang, K. Lambrinou, J. Vleugels, Sterically stabilised (Zr,Ti)-(Al,Sn,Pb,Bi)-C MAX phase solid solutions with Zn additions and enhanced chemical complexity on the A-site, Journal of the American Chemical Society 147 (2025) 41501-41513

[30] B. Tunca, S. Huang, N. Goossens, K. Lambrinou, J. Vleugels, Chemically complex double solid solution MAX phase-based ceramics in the (Ti,Zr,Hf,V,Nb)-(Al,Sn)-C system, Materials Research Letters 10 (2022) 52-61

[31] B. Anasori, M. Dahlqvist, J. Halim, E.J. Moon, J. Lu, B.C. Hosler, E.A.N. Caspi, S.J. May, L. Hultman, P. Eklund, J. Rosén, M.W. Barsoum, Experimental and theoretical characterisation of ordered MAX phases Mo2TiAlC2 and Mo2Ti2AlC3, Journal of Applied Physics 118 (2015) 094304

[32] R. Windey, N. Goossens, M. Cardous, J. Soete, J. Vleugels, M. Wevers, Exfoliating Ti3AlC2 MAX into Ti3C2Tz MXene: A powerful strategy to enhance high‐voltage dielectric performance of percolation‐based PVDF nanodielectrics, Advanced Materials Interfaces 11 (2024) 2400499

[33] M.A. Tunes, The legacy and future of aluminium alloys: Space exploration and extraterrestrial settlement, ACS Materials Au 6 (2025) 1-27

[34] M.A. Tunes, L. Stemper, G. Greaves, P.J. Uggowitzer, S. Pogatscher, Prototypic lightweight alloy design for stellar‐radiation environments, Advanced Science 7 (2020) 2002397

[35] M.A. Tunes, L. Stemper, G. Greaves, P.J. Uggowitzer, S. Pogatscher, Metal alloy space materials: Prototypic lightweight alloy design for stellar‐radiation environments, Advanced Science 7 (2020) 2070126

[36] W. Lohmann, A. Ribbens, W.F. Sommer, B.N. Singh, Microstructure and mechanical properties of medium energy (600-800 MeV) proton irradiated commercial aluminium alloys, Radiation Effects 101 (1987) 283–299

[37] P.D. Willenshofer, M.A. Tunes, H.T. Vo, L. Stemper, M. Alfreider, O. Renk, G. Greaves, D. Kiener, P.J. Uggowitzer, S. Pogatscher, Radiation-resistant aluminium alloy for space missions in the extreme environment of the solar system, Advanced Materials 2025 (2025) e13450

[email protected]

Further information

This article was produced with the support of Prof. Dr Konstantina Lambrinou, Professor of Advanced Materials at the University of Huddersfield, whose research focuses on materials for advanced nuclear systems, liquid metal corrosion mitigation, and nanostructured MAX, MXene and ZIP phase materials.

Contributing to this piece are Dr Ir. Nick Goossens, Postdoctoral Researcher at the Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology (Empa), whose work centres on the synthesis of chemically complex MAX phases and ZIP phases as precursors to tailored 2D MXene materials, and Assistant Prof, Dr Matheus A. Tunes of Montanuniversität Leoben, Austria, who leads the [X-MAT] Laboratory for Metallurgy in Extreme Environments and specialises in materials design for radiation, corrosion and extraterrestrial conditions.

To find out more about their work and institutions, visit:

University of Huddersfield — www.hud.ac.uk

Empa — www.empa.ch

Montanuniversität Leoben / X-MAT — https://x-mat.unileoben.ac.at

Read More: ‘Women, science and the price of integrity‘. From the shadow of the Acropolis to the forefront of nuclear materials research, Professor Konstantina Lambrinou reflects on ambition, injustice and moral choice in male-dominated scientific institutions. Drawing on a celebrated career spanning international laboratories, leadership roles and hard-won recognition, she examines what it truly costs women to succeed without compromising integrity, and why remaining faithful to one’s principles remains essential for those who wish to lead without losing themselves.

Do you have news to share or expertise to contribute? The European welcomes insights from business leaders and sector specialists. Get in touch with our editorial team to find out more.

Main image: Steve Johnson/Pexels

RECENT ARTICLES

-

Gen Z set to make up 34% of global workforce by 2034, new report says

Gen Z set to make up 34% of global workforce by 2034, new report says -

The ideas and discoveries reshaping our future: Science Matters Volume 3, out now

The ideas and discoveries reshaping our future: Science Matters Volume 3, out now -

Lasers finally unlock mystery of Charles Darwin’s specimen jars

Lasers finally unlock mystery of Charles Darwin’s specimen jars -

Strong ESG records help firms take R&D global, study finds

Strong ESG records help firms take R&D global, study finds -

European Commission issues new cancer prevention guidance as EU records 2.7m cases in a year

European Commission issues new cancer prevention guidance as EU records 2.7m cases in a year -

Artemis II set to carry astronauts around the Moon for first time in 50 years

Artemis II set to carry astronauts around the Moon for first time in 50 years -

Meet the AI-powered robot that can sort, load and run your laundry on its own

Meet the AI-powered robot that can sort, load and run your laundry on its own -

Wingsuit skydivers blast through world’s tallest hotel at 124mph in Dubai stunt

Wingsuit skydivers blast through world’s tallest hotel at 124mph in Dubai stunt -

Centrum Air to launch first European route with Tashkent–Frankfurt flights

Centrum Air to launch first European route with Tashkent–Frankfurt flights -

UK organisations still falling short on GDPR compliance, benchmark report finds

UK organisations still falling short on GDPR compliance, benchmark report finds -

Stanley Johnson appears on Ugandan national television during visit highlighting wildlife and conservation ties

Stanley Johnson appears on Ugandan national television during visit highlighting wildlife and conservation ties -

Anniversary marks first civilian voyage to Antarctica 60 years ago

Anniversary marks first civilian voyage to Antarctica 60 years ago -

Etihad ranked world’s safest airline for 2026

Etihad ranked world’s safest airline for 2026 -

Read it here: Asset Management Matters — new supplement out now

Read it here: Asset Management Matters — new supplement out now -

Breakthroughs that change how we understand health, biology and risk: the new Science Matters supplement is out now

Breakthroughs that change how we understand health, biology and risk: the new Science Matters supplement is out now -

The new Residence & Citizenship Planning supplement: out now

The new Residence & Citizenship Planning supplement: out now -

Prague named Europe’s top student city in new comparative study

Prague named Europe’s top student city in new comparative study -

BGG expands production footprint and backs microalgae as social media drives unprecedented boom in natural wellness

BGG expands production footprint and backs microalgae as social media drives unprecedented boom in natural wellness -

The European Winter 2026 edition - out now

The European Winter 2026 edition - out now -

Parliament invites cyber experts to give evidence on new UK cyber security bill

Parliament invites cyber experts to give evidence on new UK cyber security bill -

EU sustainability rules drive digital compliance push in Uzbekistan ahead of export change

EU sustainability rules drive digital compliance push in Uzbekistan ahead of export change -

AI boom triggers new wave of data-centre investment across Europe

AI boom triggers new wave of data-centre investment across Europe -

Lammy travels to Washington as UK joins America’s 250th anniversary programme

Lammy travels to Washington as UK joins America’s 250th anniversary programme -

China’s BYD overtakes Tesla as world’s largest electric car seller

China’s BYD overtakes Tesla as world’s largest electric car seller -

FTSE 100 posts strongest annual gain since 2009 as London market faces IPO test

FTSE 100 posts strongest annual gain since 2009 as London market faces IPO test