Drowning in silence: why celebrity inaction can costs lives

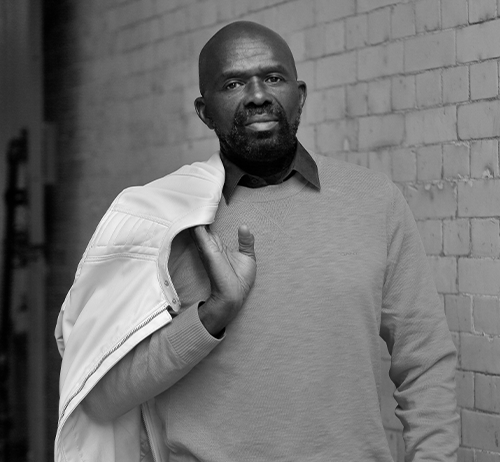

Ed Accura

- Published

- Opinion & Analysis

Campaigner and filmmaker Ed Accura says Britain’s water safety crisis is being met with indifference from those who could make the greatest difference. Despite years of appeals, celebrities and their managers have largely ignored calls to support campaigns such as 3S (Stop, See, Swim) and NO Lifeguard — initiatives that could save lives and change a culture of neglect

In Britain, we have a peculiar relationship with water. For a nation built on maritime history — an island whose prosperity, power, and mythology all stem from the sea — we are oddly disconnected from it. That disconnection is cultural, educational, and, for many, fatal. Every year, dozens of lives are lost in British waters that could have been saved through something as simple as basic water safety and swimming competence.

For years, I have been working to change that. My focus has been on the lack of engagement with aquatics among Black and Asian communities, a crisis that continues to be neglected despite its obvious human cost. The problem is cultural as much as structural, and in today’s world, culture is shaped by influence.

That is why I have repeatedly appealed to celebrities to lend their voices to this cause. The cultural absence surrounding swimming in some communities is reinforced by the absence of relatable figures promoting it. A single high-profile voice could change that.

The transformative power of celebrity involvement cannot be overstated: it can shift perceptions, normalise behaviour, and make life-saving habits aspirational. But for all the moral slogans and social campaigns that dominate celebrity culture, this particular issue has been met largely with silence. My agent and I have written to dozens of household names and to their management teams, celebrities who command enormous followings and who regularly post (and sing) about social justice, diversity, and empowerment.

Not one has meaningfully responded.

They know who they are. I feel profoundly disappointed by that silence. It is not an exaggeration to say that indifference of this kind costs lives.

According to Sport England’s 2024 survey, 97 per cent of Black adults and 82 per cent of Black children in England do not swim. Among Asian communities, the figures are 96 per cent of adults and 79 per cent of children. The correlation between those statistics and the UK’s drowning data is direct and devastating.

Black children are seven times more likely to die from drowning than their white peers. For white or white British children, the fatality rate is 1.87 per million; for Asian and Asian British, it rises to 2.86 per million; and for mixed-heritage children, 3 per million.

These tragic deaths might have been prevented through early exposure, education, and awareness. When an entire section of society grows up without a relationship with water, not knowing how to swim, how to recognise risk, or how to save themselves or others, the consequences are inevitable.

The reasons for it are layered. Some are practical: access, affordability, transport, and the availability of culturally sensitive facilities. Others are psychological and historical. For many families, the fear of water is inherited. Parents who cannot swim often pass on anxiety to their children. Concerns about hair, modesty, and body image create further distance, and one that constantly comes up, the lack of relatability.

And when television, advertising, and social media offer no images of people who look like you enjoying or mastering water, the perception hardens that swimming “isn’t for us”. Representation matters, and the power of seeing someone you identify with doing something once seen as unattainable cannot be overstated. That is precisely where celebrity influence should come in, yet remarkably, it has not.

In an age where social media shapes aspiration more than any textbook or teacher, public figures, or even parents, hold a responsibility commensurate with their reach. A celebrity endorsement can achieve in one week what years of public information campaigns struggle to do. It can render something desirable, fashionable, even.

Imagine if even a fraction of the energy spent on promoting fitness products, clothing lines, or charity galas were redirected to promoting swimming competence, water safety, and respect for aquatic environments. One video of a global star learning to swim, encouraging others to do the same, would carry more weight than any poster campaign.

Celebrities frequently use their platforms to speak about inequality, mental health, representation, knife crime, and justice, all of which are admirable. Yet the failure to engage with a crisis that disproportionately affects the same communities they claim to represent reveals a striking inconsistency.

In my documentary series Changing the Narrative, released during Black History Month 2024, I sought to break the silence. The five-part project aimed to show the emotional and cultural roots of aquatic exclusion and to begin a conversation about change. The response was overwhelmingly positive. Viewers recognised themselves in the stories and voiced a desire to do better for the next generation.

Both the “Changing the Narrative” and “Blacks Can’t Swim” documentaries feature young people sharing lived experience, and make clear how celebrity culture and visible role models shape decisions about swimming.

But one campaigner can only do so much, as I have a limited reach. Systemic change requires scale, and scale requires visibility. That visibility could come easily if even a handful of public figures acted.

The same truth underpins the NO Lifeguard campaign, a national awareness initiative aimed at preventing unintentional drownings. Its message is disarmingly simple: swim only in lifeguarded areas. The statistics are once again sobering. In 2023, 63 per cent of accidental drownings in the UK involved men in seas, lakes, or rivers, most of them occasional swimmers, often acting spontaneously on hot days. They were untrained, unsupervised, and unaware of the hidden dangers beneath the surface.

Alongside this sits the 3S Motion Campaign — Stop, See, Swim — a national initiative I developed to promote three simple, life-saving principles. Stop means checking if a lifeguard is present before entering the water. See means checking for dangers, including warning flags. And Swim means ensuring you can be seen in the water and swimming only where lifeguards can see you and keep you safe.

The 3S Motion campaign is built on the principle that small, consistent behavioural changes save lives. It requires repetition, recognition, and reinforcement, precisely the kind of amplification that only celebrity influence can provide. A well-known face sharing a short video about the 3S principles could reach millions in minutes, embedding awareness that might otherwise take years to achieve through traditional education.

To speak out on this issue requires no great courage. It does not risk alienating sponsors or dividing followers. It is a universal cause that cuts across race, class, gender, and politics. Yet, for reasons that may speak to the performative nature of modern celebrity activism, almost no one has taken it on.

The contradiction is glaring. Many of the same figures who lend their voices to “awareness campaigns” that flatter their brand remain silent on a problem that costs lives. They are quick to embrace symbolic causes but reluctant to engage in ones that demand sustained, unglamorous effort, particularly if they fall outside the media’s seasonal spotlight.

Some have questioned the timing of the campaign. Launching it in autumn and winter, when few people swim, may seem counterintuitive. But behavioural change is cumulative. The winter months are the period to educate, to normalise conversations, to lay the groundwork for the summer ahead. By spring, when the first warm weekends draw people to rivers and beaches, the message must already be embedded.

That is why the silence now, in the off-season, is so damaging. Each lost month of inaction risks another preventable summer of tragedy.

No single campaign can undo generations of disengagement from aquatics. But we can shift the trajectory. We can normalise water safety and swimming within communities where it has too often been seen as inaccessible or irrelevant. That shift begins with awareness, and awareness begins with visibility.

If the UK’s celebrity class, the actors, athletes, musicians, influencers, used even a fraction of their reach to promote swimming and water safety, the results would be transformative. They could help create a cultural expectation that knowing how to swim is not optional, but essential.

I have sent countless messages, emails, and formal appeals to individuals and agencies that could have made that difference. Most went completely unanswered, despite being read. Some promised to “pass it on to the talent” and seemingly never did. It is difficult not to conclude that many of those who talk about saving the world have not yet recognised this particular opportunity to help save a child from drowning.

The next time a tragedy makes headlines, and the same public figures post condolences on social media, I hope they remember this: they were invited to act long before the headlines.

Ed Accura is a British filmmaker, musician and advocate whose work focuses on public safety, community inclusion and cultural change. He is the co-founder of the Black Swimming Association, which promotes diversity in aquatics through education and awareness, and the creator of the Blacks Can’t Swim and Changing the Narrative documentary series. His films, released on platforms including Amazon Prime, Sky, Apple TV and Google Play, have been credited with transforming national conversations around water safety and representation. For The European, he writes on public safety, inclusion and the social impact of culture.

READ MORE: ‘Drowning is a public health crisis. Governments must treat it that way‘. From children in Spain to athletes in Portugal and actors in Costa Rica, 2025 has already seen too many lives lost to water. Filmmaker Ed Accura, co-founder of the Black Swimming Association, argues that drowning must finally be treated as a global public health emergency.

Do you have news to share or expertise to contribute? The European welcomes insights from business leaders and sector specialists. Get in touch with our editorial team to find out more.

Sign up to The European Newsletter

RECENT ARTICLES

-

Drowning in silence: why celebrity inaction can costs lives

Drowning in silence: why celebrity inaction can costs lives -

The lost frontier: how America mislaid its moral compass

The lost frontier: how America mislaid its moral compass -

Why the pursuit of fair taxation makes us poorer

Why the pursuit of fair taxation makes us poorer -

In turbulent waters, trust is democracy’s anchor

In turbulent waters, trust is democracy’s anchor -

The dodo delusion: why Colossal’s ‘de-extinction’ claims don’t fly

The dodo delusion: why Colossal’s ‘de-extinction’ claims don’t fly -

Inside the child grooming scandal: one officer’s story of a system that couldn’t cope

Inside the child grooming scandal: one officer’s story of a system that couldn’t cope -

How AI is teaching us to think like machines

How AI is teaching us to think like machines -

The Britain I returned to was unrecognisable — and better for It

The Britain I returned to was unrecognisable — and better for It -

We built an education system for everyone but disabled students

We built an education system for everyone but disabled students -

Justice for sale? How a £40 claim became a £5,000 bill in Britain’s broken Small Claims Court

Justice for sale? How a £40 claim became a £5,000 bill in Britain’s broken Small Claims Court -

Why control freaks never build great companies

Why control freaks never build great companies -

I quit London’s rat race to restore a huge crumbling estate in the Lake District

I quit London’s rat race to restore a huge crumbling estate in the Lake District -

The grid that will decide Europe’s future

The grid that will decide Europe’s future -

Why Gen Z struggles with pressure — and what their bosses must do about it

Why Gen Z struggles with pressure — and what their bosses must do about it -

What Indian philosophy can teach modern business about resilient systems

What Indian philosophy can teach modern business about resilient systems -

AI can’t swim — but it might save those who do

AI can’t swim — but it might save those who do -

The age of unreason in American politics

The age of unreason in American politics -

Digitalization, financial inclusion, and a new era of banking services: Uzbekistan’s road to WTO membership

Digitalization, financial inclusion, and a new era of banking services: Uzbekistan’s road to WTO membership -

Meet Omar Yaghi, the Nobel Prize chemist turning air into water

Meet Omar Yaghi, the Nobel Prize chemist turning air into water -

Behind the non-food retail CX Benchmark: what the numbers tell us about Europe’s future

Behind the non-food retail CX Benchmark: what the numbers tell us about Europe’s future -

Why NHS cancer care still fails disabled people

Why NHS cancer care still fails disabled people -

Echoes of 1936 in a restless and divided Britain

Echoes of 1936 in a restless and divided Britain -

Middle management still holds the power leaders need

Middle management still holds the power leaders need -

Trump and painkillers: The attack on science is an attack on democracy

Trump and painkillers: The attack on science is an attack on democracy -

The end of corporate devotion? What businesses can learn from Gen Z

The end of corporate devotion? What businesses can learn from Gen Z