Laying the foundations for sustainable cities

John E. Kaye

- Published

- Home, Sustainability

Whilst Europe is at the forefront of developing more environmentally-friendly cities, there is still work to be done, says Jan-Maurits Loecke of architecture firm, CallisonRTKL

Throughout Europe, cities and towns are already being transformed with a strong commitment to environmental and social sustainability and growth. As architects and urban designers, it is quite simple – our commitment to people, planet and positive design is now a necessity, not a luxury.

CallisonRTKL (CRTKL) is already committed to performance driven design, our latest sustainability report “Shaping a Better World” goes even further, applying the greatest available intelligence to create compelling design that improves the value of the built environment, while avoiding impact on the natural environment. We have to measure where we are and where we go to in order to avoid further damage to the planet, and we cannot downplay the importance of data and intelligence we now have available.

While we are making progress globally, there is still a lot more to be done, including better industry-wide collaboration, stricter legislation and more government incentives. We also need more research and training for a true net zero built environment from cradle to grave.

Understanding the challenges

The good news is, that on the world stage, Europe is already leading the way on many fronts. For example, the Council on Tall Buildings highlights that Europe is at the leading edge of a timber construction movement, while also making strong progress in modular construction and additive manufacturing (also known as 3D printing), which is expected to boost the prefabricated construction sector significantly. However, we must not stop there. We need to continually research and test new methods and materials. Just look at the automotive industry as an example of a sector that continues to evolve at pace.

Of course, this race to a sustainable future is not without obstacles. Many European cities have been heavily inhabited over centuries, with their layouts reflecting this heritage. In more dense areas, the existing building infrastructure partly determines how fast new development or retrofitting existing buildings can take place. Where possible, we should be looking at adaptive reuse and restoration, and if new buildings do need to be created then they must be done so with a strict sustainability agenda, both environmentally as well as socially. Eco-friendly buildings are just one part of the equation. For true success, we must consider the mix of buildings and how they integrate with each other and those that use them. The concept of the 15-minute district, where all needs are satisfied within walking or cycling distance from home, is central to our cities’ successful future. At the same time, possible side effects of renewed segregation within the urban texture need to be taken into account and solutions found.

Carlos Moreno, the Franco-Colombian scientist and university professor, first proposed the model in 2016, and cities like Paris and Milan have been at the forefront of actually delivering on this, before the pandemic begun. Now, it is time for other cities including those in the UK, to take note and learn. Remember, there is no point designing the world’s most sustainable building or cluster of buildings, if all of the habitants drive there in emission-heavy petrol or energy hungry cars.

Positive examples of sustainable development in Europe include Merlata Bloom, a vast new “lifestyle centre” that we at CRTKL are working on. The development will blend retail, food & beverage, immersive entertainment, office space and more, all set amongst beautiful landscaping and biodiverse gardens – in fact the building almost merges with the adjacent Merlata park. This project shows a possible way of designing a sustainable building, highly contextual, sympathetic with the local climate using hybrid wood materials and influenced by in depth parametric design exercises, solar studies, material reduction.

In Madrid, we have worked on Torre Europa, a sustainable retrofit of one of the Spanish capital’s most iconic towers to ensure its future legacy, while nearby we have breathed new life into Castellana 66, an office project built in 1990 which now 30 years later needed to be upgraded with current building standards in terms of acoustics, energy efficiency and carbon emissions. Rather than demolish the building and design a new one, a careful design upgrade for the facade has been carried out to create a high-performance envelope with integrated photovoltaics, along with other improvements that create a more appealing development overall.

The road ahead

So, what else can be done to advance sustainability? At policy level, the demand could be very simple indeed, but the industry is not there yet. German Engineer Werner Sobek has suggested the radical idea that governments dictate: “Any emission of carbon dioxide or other greenhouse gases and any other substances that are harmful to people and the environment should be avoided during the production, operation and dismantling of the building (from a point in time to be agreed), while unavoidable process-related emissions are to be offset by compensation measures.”

Net zero building cost is something that is regularly flagged as a barrier; there is a parallel analogy to food as eating healthy costs more. However, the reality is that many strategies can be implemented with minimal additional costs and in the long-term, the building will be cheaper to operate. It is only through wider adoption that these costs come down and sustainability can become mainstream, not a luxury.

As a practice, we at CRTKL are dedicated to this mission, however all of the above can only be achieved together with cross-disciplinary collaboration across generations, stakeholders, academia and the end user. This is the only way net zero culture will really work.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jan-Maurits Loecke is Associate Principal and a Global Sustainability Fellow at architecture firm CallisonRTKL.

Further information

RECENT ARTICLES

-

Strong ESG records help firms take R&D global, study finds

Strong ESG records help firms take R&D global, study finds -

How residence and citizenship programmes strengthen national resilience

How residence and citizenship programmes strengthen national resilience -

Global leaders enter 2026 facing a defining climate choice

Global leaders enter 2026 facing a defining climate choice -

EU sustainability rules drive digital compliance push in Uzbekistan ahead of export change

EU sustainability rules drive digital compliance push in Uzbekistan ahead of export change -

China’s BYD overtakes Tesla as world’s largest electric car seller

China’s BYD overtakes Tesla as world’s largest electric car seller -

UK education group signs agreement to operate UN training centre network hub

UK education group signs agreement to operate UN training centre network hub -

Mycelium breakthrough shows there’s mush-room to grow in greener manufacturing

Mycelium breakthrough shows there’s mush-room to grow in greener manufacturing -

Oxford to host new annual youth climate summit on UN World Environment Day

Oxford to host new annual youth climate summit on UN World Environment Day -

Exclusive: Global United Nations delegates meet in London as GEDU sets out new cross-network sustainability plan

Exclusive: Global United Nations delegates meet in London as GEDU sets out new cross-network sustainability plan -

Fast fashion brands ‘greenwash’ shoppers with guilt-easing claims, study warns

Fast fashion brands ‘greenwash’ shoppers with guilt-easing claims, study warns -

Private sector set to overtake government as main driver of corporate sustainability in 2026, report suggests

Private sector set to overtake government as main driver of corporate sustainability in 2026, report suggests -

Sir Trevor McDonald honoured at UWI London Benefit Dinner celebrating Caribbean achievement

Sir Trevor McDonald honoured at UWI London Benefit Dinner celebrating Caribbean achievement -

Historic motorsport confronts its energy future

Historic motorsport confronts its energy future -

Protecting the world’s wild places: Dr Catherine Barnard on how local partnerships drive global conservation

Protecting the world’s wild places: Dr Catherine Barnard on how local partnerships drive global conservation -

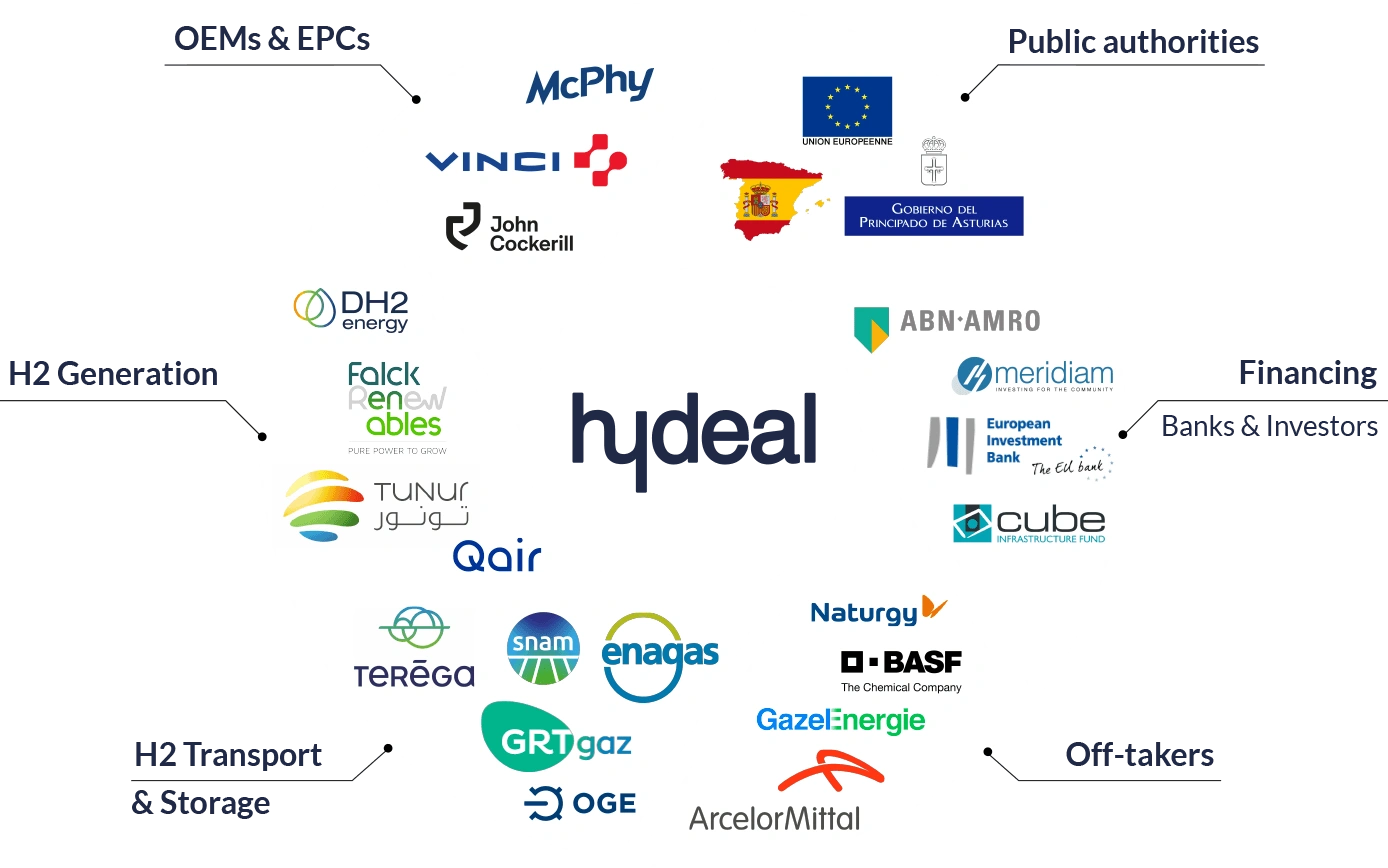

Europe’s HyDeal eyes Africa for low-cost hydrogen link to Europe

Europe’s HyDeal eyes Africa for low-cost hydrogen link to Europe -

Fabric of change

Fabric of change -

Courage in an uncertain world: how fashion builds resilience now

Courage in an uncertain world: how fashion builds resilience now -

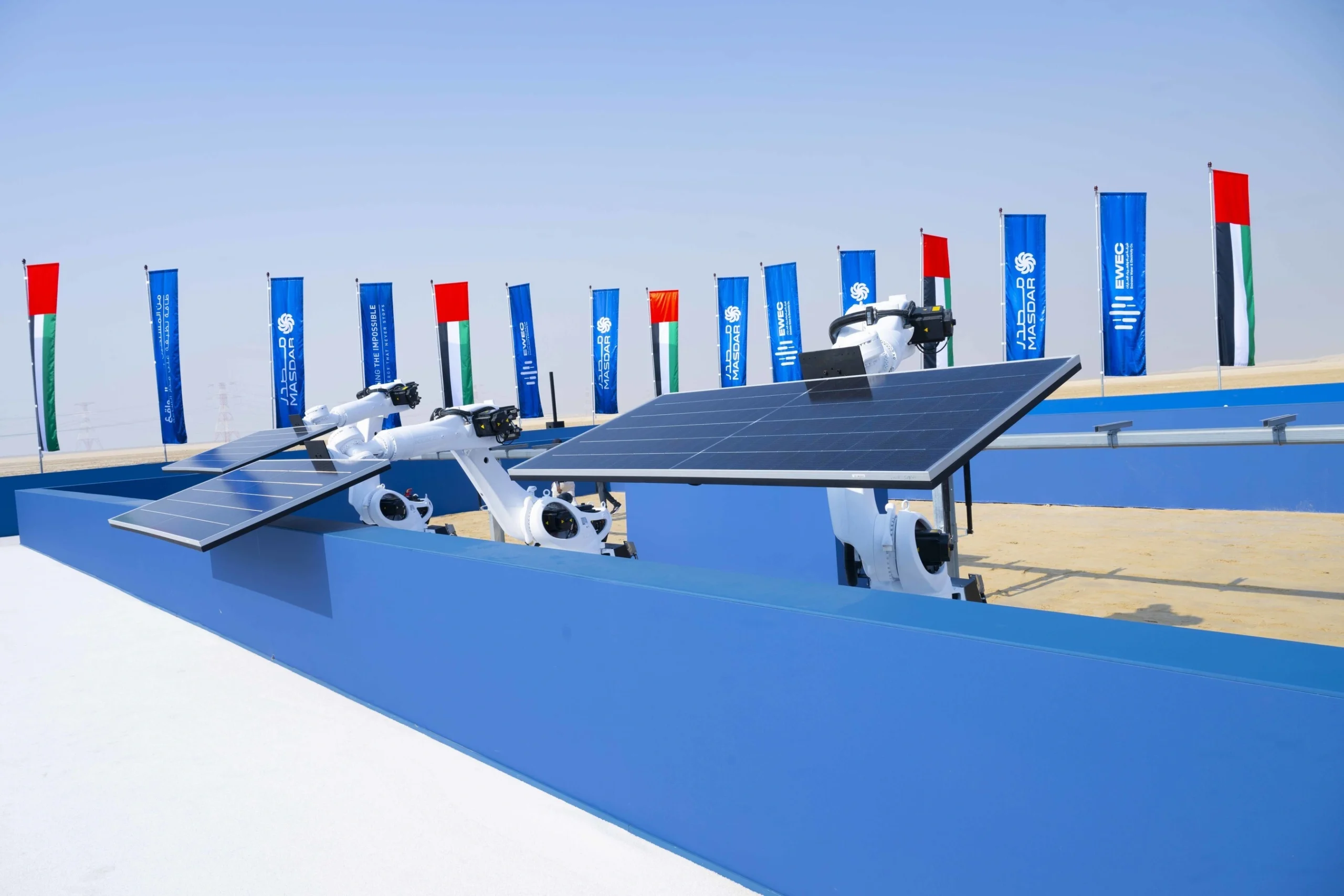

UAE breaks ground on world’s first 24-hour renewable power plant

UAE breaks ground on world’s first 24-hour renewable power plant -

China’s Yancheng sets a global benchmark for conservation and climate action

China’s Yancheng sets a global benchmark for conservation and climate action -

Inside Iceland’s green biotechnology revolution

Inside Iceland’s green biotechnology revolution -

Global development banks agree new priorities on finance, water security and private capital ahead of COP30

Global development banks agree new priorities on finance, water security and private capital ahead of COP30 -

UK organisations show rising net zero ambition despite financial pressures, new survey finds

UK organisations show rising net zero ambition despite financial pressures, new survey finds -

Gulf ESG efforts fail to link profit with sustainability, study shows

Gulf ESG efforts fail to link profit with sustainability, study shows -

Redress and UN network call for fashion industry to meet sustainability goals

Redress and UN network call for fashion industry to meet sustainability goals -

World Coastal Forum leaders warn of accelerating global ecosystem collapse

World Coastal Forum leaders warn of accelerating global ecosystem collapse