Supercharging the green transition

John E. Kaye

- Published

- Home, Sustainability

Tackling climate change requires more positive incentives and fewer taxes, argues Eric Lonergan in a new book. Alex Katsomitros catches up with him.

The semi-final of this year’s French Open between Casper Ruud and Marin Cilic took a wild turn when a young woman entered the court, catching everyone by surprise. After swiftly tying herself to the net, she sat on her knees motionless, letting the message on her T-shirt speak for itself: “We have 1,028 days left”. Unsurprisingly, the interruption elicited a prolonged boo from the crowd.

It is such an unpopular, yet prescient sense of urgency about climate change that we have to embrace, argue Eric Lonergan and Corinne Sawers in their new book Supercharge Me: Net Zero Faster. An acclaimed economist and climate expert respectively, as well as a couple, Lonergan and Sawers praise activists who have a disproportionate influence in changing accepted norms, defying the boos and the heckles. “If you’re more interested in tennis than global warming, history is not on your side,” Lonergan says on a Zoom call from his home in London, adding: “The history of activism tells us that people who are right are usually quite unpopular. Martin Luther King was not necessarily the most popular man in America when he was campaigning, but now he’s a national hero.”

No time to tax

As a fund manager at M&G Investments, a London-based investment firm, Lonergan speaks from a unique vantage point. He acknowledges that, just like the Roland Garros intruder, current measures against climate change can be unpopular. A case in point is France’s Yellow Vest movement, which rose in opposition to a fuel tax rise. If policymakers want to win hearts and minds, he argues, they need to start with the financial impacts of climate policy. “The way to win over the population is by using ethics and making green options cheaper,” he says, adding: “We need to stop all these green taxes, because if people associate the green transition with taxation, it’s a disaster politically. And there’s no reason why they should – it’s bad economics.”

The book, Lonergan reminisces, was born out of frustration with existing literature on climate change. Jargon-filled and often overly theoretical, it is short on practical solutions. “Climate change is a much more solvable problem than frequently presented,” he says with an Irish lilt, betraying his Dublin upbringing.

“Most books about climate change would make you think that we have to make dramatic sacrifices, but we just need to make our life sustainable, and that’s an investment problem.”

An EPIC transition

It is this kind of optimism that permeates the book, written as a dialogue between the two authors, that sets it apart from the techno-utopianism that often taints climate discourse. Unlike many other experts, Lonergan and Sawers believe that we already have the necessary technologies to tackle climate change – we just need the financial incentives to use them. Traditionally, economists treat carbon emissions as an externality that is not captured by markets, so carbon taxes are supposed to set the price right. The problem, according to Lonergan, is that such punitive measures tend to irk people, rather than persuade them to go green. “Carbon taxes are successful at raising revenue, but unsuccessful at changing our behaviour,” he says. An example is the UK where take-up of electric vehicles is still low, despite one of the highest fuel duties in Europe. The reason, Lonergan argues, is that consumers don’t have access to a cheap alternative.

That’s where the book’s big idea kicks in: Extreme Positive Incentives for Change (EPICs), which according to Lonergan are almost the opposite of a carbon tax. For every polluting activity, policymakers need to find a substitute and offer people an incentive to adopt it, notably by making it cheaper. Lonergan cites Norway’s electric vehicle policy as an example, which encourages electric vehicle ownership through discounts on taxes, tolls and parking fees, not to mention the cheaper price of the car itself. The result is that more than nine out of ten new cars sold in the country are electric. The same principle applies to our eating habits: “If you went into McDonald’s or Burger King and the plant-based alternative was 30% cheaper than beef-based cheeseburgers, the evidence says you would get a big change in behaviour,” Lonergan says.

The big EPIC that could supercharge the green transition is sustainable electricity. Our priority, Lonergan argues, should be to supplant fossil fuels with wind, solar and perhaps nuclear energy and electrify everything, from transport and home heating to manufacturing. Here, the couple’s theory deviates from conventional wisdom. If most pundits believe that tackling climate change requires dramatic sacrifices, Lonergan and Sawers choose to focus on the bright side. All we need to do, Lonergan says, is to consider the high returns on investment in green energy, just like comparing mortgage payments and rent costs before deciding whether to take a mortgage. “In the developed world today, our cost of capital is incredibly low, and the return is higher. With solar and wind energy, we can have a return of at least 4%,” Lonergan says, arguing that making electricity green is a net wealth creator. Incidentally, that would also result in lower electricity prices, given that wind and solar energy generates cheaper electricity than fossil fuels. Spiking oil and gas prices have sent inflation rates through the roof, but according to Lonergan, the war in Ukraine is not the only culprit. “We have had lots of boom-and-bust in agricultural and fossil fuel prices and that’s inherent in the market. The prices will always be volatile,” he says.

Eric Lonergan

Governments take centre stage

For EPICs to work, governments would need to take a more active role. It is a prospect that spooks free-market advocates, fearing a regulatory boom similar to what happened during the pandemic when government officials were dictating the smallest minutiae of economic life. Lonergan, however, is not keen on ideology. If economics has taught him something, it is pragmatism. “There are some broad principles we can apply universally, like sustainable electrification, but questions like whether a country should have a state electricity company should be dealt with on a case-by-case basis,” he says. The problem, he argues, is not capitalism, but institutions captured by vested interests, such as the US coal lobby blocking green regulation: “We can collapse emissions within the current economic structure. It is a question of political will.” His proposed solution includes creating competing vested interests and using the state’s financial firepower and regulation to support green ones, for example through a “contingent carbon tax” on corporate profits for firms that do not comply with best practice on emissions.

One area where that is easier said than done is monetary policy. Many central bankers would laugh at the idea that their institutions should have an environmental mandate. Lonergan believes it should be as important as tackling inflation, pointing out that we should take advantage of low interest rates to invest in green energy, even if the argument may be losing its appeal in an era of rising rates. “The primary function of central banks is price stability, but supporting the environment through intelligent carbon-reducing policies would be complementary to that,” he says. He cites the EU’s sustainable finance policy as an example, which aims to accelerate investment in renewable energy. “Having targeted lending programmes that encourage banks to lend to these sectors [solar and wind] at low rates would help reduce inflation,” he says. Overall, central banks need a long-term plan, rather than sticking plasters on the corpse of the old economy: “Next time there’s a recession, instead of fuelling house and stock prices, which is ultimately deflationary, why not target lending stimulus in those sectors that are more sustainable?”

Tapping into eco-nationalism

Almost counterintuitively, one of the tools Lonergan and Sawers believe we can use to fight climate change is the rise of nationalism. Under the Trump administration the US withdrew from the Paris Agreement, while Poland’s ultra-conservative government has refused to close down coal plants. In his previous book, Angynomics, co-authored with the political economist Mark Blyth, Lonergan explored the economic origins of modern populism. However, staying true to his pragmatist credentials, he argues that we can make a virtue out of the obsession of nationalists with sovereignty, particularly when it comes to China and India. “Renewable electricity can be a form of self-sufficiency,” he says, adding: “People underestimate how motivated China is to collapse its demand for fossil fuels,” notably by becoming a leader in alternative energy technology in areas such as concentrated solar power, which doesn’t require battery storage.

Global action is also necessary. Lonergan and Sawers envisage global trade agreements for emission-heavy sectors like steel and cement, ESG scores for government debt and an overhaul of international organisations to focus on climate change. In other words, a “Green Bretton Woods”, an idea not terribly original but appealing nevertheless. If the cement and the steel industries need to reduce emissions by 90% in the next decade, EU regulators should ban imports that don’t meet the bloc’s standards, Lonergan believes. Surely some constituents may disagree. But overall, the question of who will pay for the green transition is easier to answer than usually thought. “There’s no reason why climate change needs to be a huge burden for the overwhelming majority of the population,” he says. “The people who are going to lose are the owners of the fossil fuel assets. It’s a lot of money, but it’s a small share of global wealth, owned by a small share of the population. The majority should be positive about it.”

Buy Eric’s book, Supercharge Me: Net Zero Faster from: Waterstones | Amazon | WHSmiths

RECENT ARTICLES

-

Strong ESG records help firms take R&D global, study finds

Strong ESG records help firms take R&D global, study finds -

How residence and citizenship programmes strengthen national resilience

How residence and citizenship programmes strengthen national resilience -

Global leaders enter 2026 facing a defining climate choice

Global leaders enter 2026 facing a defining climate choice -

EU sustainability rules drive digital compliance push in Uzbekistan ahead of export change

EU sustainability rules drive digital compliance push in Uzbekistan ahead of export change -

China’s BYD overtakes Tesla as world’s largest electric car seller

China’s BYD overtakes Tesla as world’s largest electric car seller -

UK education group signs agreement to operate UN training centre network hub

UK education group signs agreement to operate UN training centre network hub -

Mycelium breakthrough shows there’s mush-room to grow in greener manufacturing

Mycelium breakthrough shows there’s mush-room to grow in greener manufacturing -

Oxford to host new annual youth climate summit on UN World Environment Day

Oxford to host new annual youth climate summit on UN World Environment Day -

Exclusive: Global United Nations delegates meet in London as GEDU sets out new cross-network sustainability plan

Exclusive: Global United Nations delegates meet in London as GEDU sets out new cross-network sustainability plan -

Fast fashion brands ‘greenwash’ shoppers with guilt-easing claims, study warns

Fast fashion brands ‘greenwash’ shoppers with guilt-easing claims, study warns -

Private sector set to overtake government as main driver of corporate sustainability in 2026, report suggests

Private sector set to overtake government as main driver of corporate sustainability in 2026, report suggests -

Sir Trevor McDonald honoured at UWI London Benefit Dinner celebrating Caribbean achievement

Sir Trevor McDonald honoured at UWI London Benefit Dinner celebrating Caribbean achievement -

Historic motorsport confronts its energy future

Historic motorsport confronts its energy future -

Protecting the world’s wild places: Dr Catherine Barnard on how local partnerships drive global conservation

Protecting the world’s wild places: Dr Catherine Barnard on how local partnerships drive global conservation -

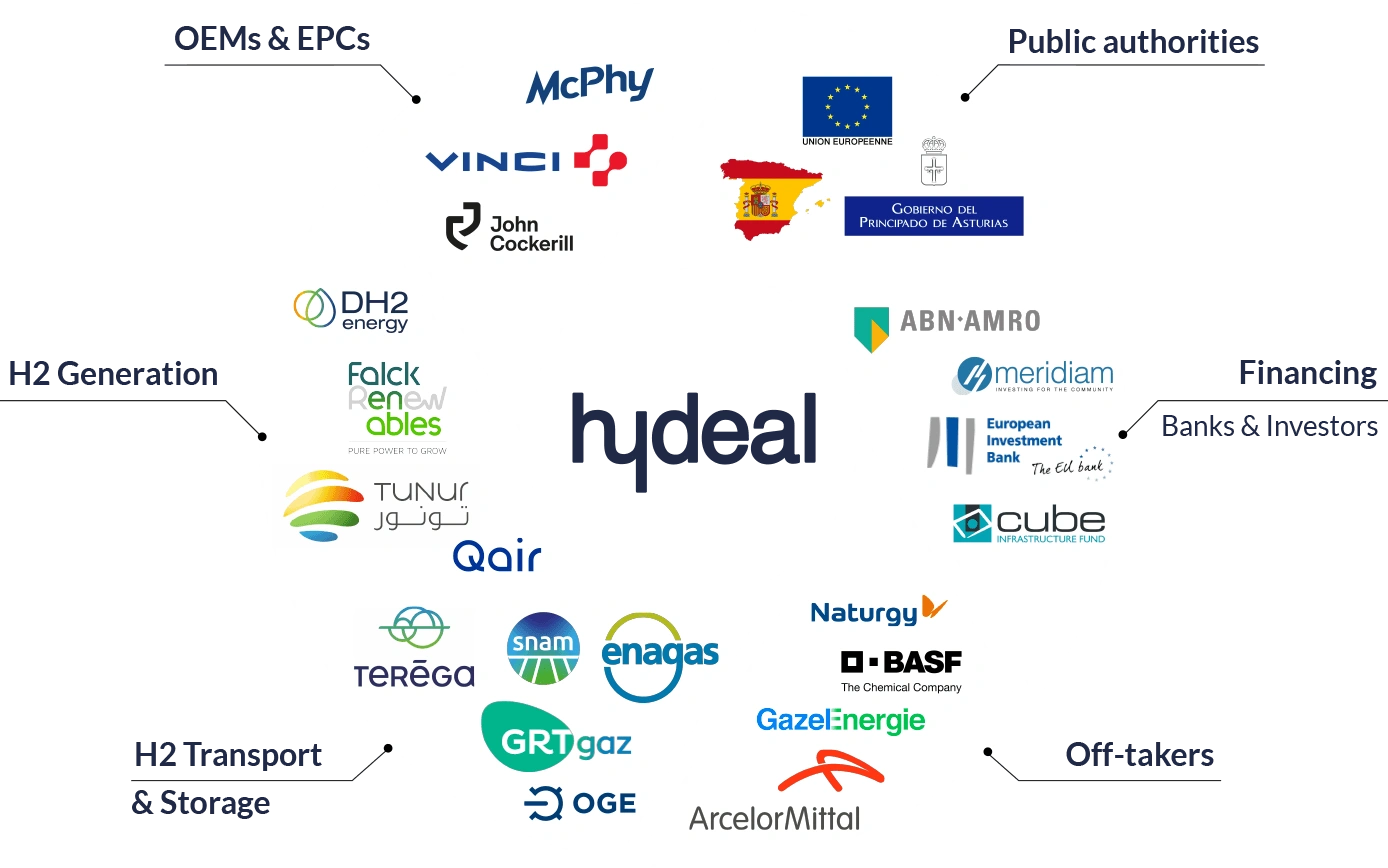

Europe’s HyDeal eyes Africa for low-cost hydrogen link to Europe

Europe’s HyDeal eyes Africa for low-cost hydrogen link to Europe -

Fabric of change

Fabric of change -

Courage in an uncertain world: how fashion builds resilience now

Courage in an uncertain world: how fashion builds resilience now -

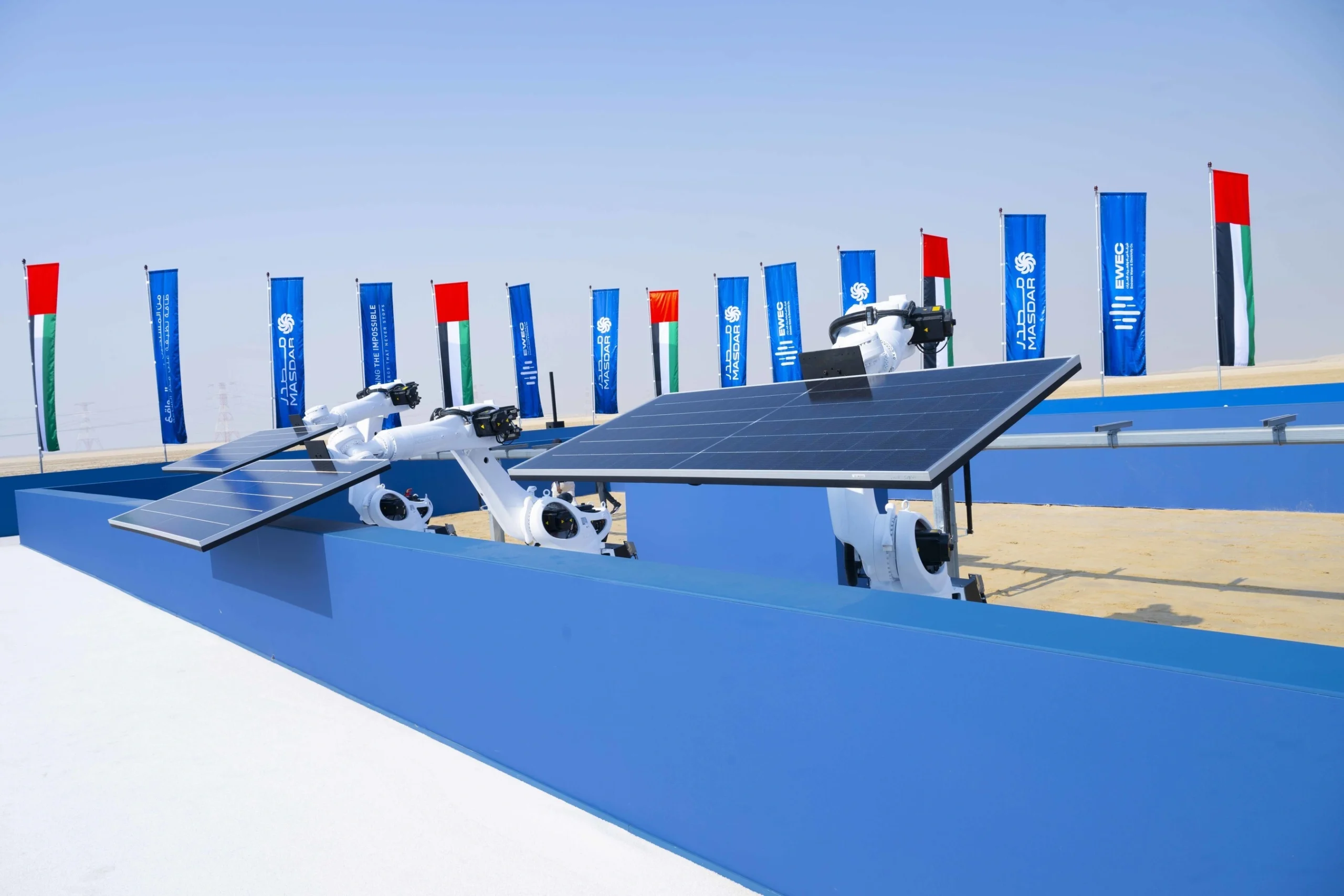

UAE breaks ground on world’s first 24-hour renewable power plant

UAE breaks ground on world’s first 24-hour renewable power plant -

China’s Yancheng sets a global benchmark for conservation and climate action

China’s Yancheng sets a global benchmark for conservation and climate action -

Inside Iceland’s green biotechnology revolution

Inside Iceland’s green biotechnology revolution -

Global development banks agree new priorities on finance, water security and private capital ahead of COP30

Global development banks agree new priorities on finance, water security and private capital ahead of COP30 -

UK organisations show rising net zero ambition despite financial pressures, new survey finds

UK organisations show rising net zero ambition despite financial pressures, new survey finds -

Gulf ESG efforts fail to link profit with sustainability, study shows

Gulf ESG efforts fail to link profit with sustainability, study shows -

Redress and UN network call for fashion industry to meet sustainability goals

Redress and UN network call for fashion industry to meet sustainability goals -

World Coastal Forum leaders warn of accelerating global ecosystem collapse

World Coastal Forum leaders warn of accelerating global ecosystem collapse