Can investors save the planet?

John E. Kaye

- Published

- Banking & Finance, Home, Sustainability

Alex Katsomitros speaks to FT writer and author of a new book Alice Ross about the green outlook shaping the world of finance, and how investors can steer the planet to safety

Three years ago, Japan’s government pension fund committed itself to an idiosyncratic exercise: gauge the “temperature” of its investment portfolio. The fund’s managers scrutinised its holdings in companies around the world with an eye on whether they aligned with a world of “net zero” carbon emissions. Despite the fund’s reputation for being a leader in sustainable investment, the results were disappointing. Its portfolio would lead to a temperature rise of 3.7C, a far cry from the 2C above pre-industrial levels set by the United Nations as the maximum to avert a climate catastrophe.

The rise of environmental finance

The story is symbolic of a broader shift in finance, argues Alice Ross, Deputy News Editor at the Financial Times, in her book Investing to Save The Planet: How Your Money Can Make a Difference – which looks at investment strategies with a green twist. “I think it is genuine. People know that climate change is here and that we need to do something about it,” Ross says over Zoom from the FT’s office in London. “Companies are worried about investors leaving them if they don’t do something about it.”

Like many other experts writing on the subject, Ross feels that the stakes are both enormous and personal. In the summer of 2019, a perfect storm of ecological pessimism took the world by surprise: the Amazon rainforest was burning; a report from the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change came out, warning about the consequences of inaction; that July was the hottest month on record. It was all just too depressing. “I was feeling quite stressed about it on a personal level,” Ross recalls.

As the Wealth Editor of the Financial Times at the time, she could observe the environmental crisis unfolding from a unique vantage point. Being a frequent interlocutor of some of the world’s richest people, she could discern a subtle change – the heart of the beast was getting softer, and greener. “I was talking to members of the next generation, people who were inheriting money and increasingly were telling me that they were interested in environmental issues. A lot of them were looking into climate tech options,” Ross explains. She realised that the insights and knowledge she could access through her job could help her – and her readers – feel more hopeful about our common future. The result is a book that delves into an up-and-coming wave of investors, funds and firms that dare to look beyond next quarter’s profits.

Fifty shades of green

Despite their enthusiasm and vast resources, green-minded investors face the same problem as journalists covering environmental finance. Large corporations have rushed to ride the wave of green newspeak, blurring the boundaries between fact and fiction. Maersk, Volkswagen and Nestlé have all committed to net zero emissions by 2050, followed by energy firms including Total, BP and Shell. Financial powerhouses have taken notice too. In December 2019, Goldman Sachs became the first major bank to rule out financing for oil and gas drilling operations in the Arctic. So, what is green when everything is “green”?

It is a question that haunts the industry, says Ross, who has been covering financial markets for 13 years. Having received loads of “ridiculous promotions of funds by PR companies and fund management houses”, aiming to “greenwash” activities that are anything but green, she has learned tο be skeptical. The rise of environmental, social and corporate governance (ESG) funds has added substance to what was often regarded as corporate propaganda: “Frequently they will call themselves green. And then it turns out, they are not actually green,” Ross says.

Their performance has also come under scrutiny lately. At the peak of the pandemic, ESG funds were praised for outperforming the market. Since then, their results have been lacklustre at best. Critics also claim that previous success was largely a result of including tech companies, whose stock prices went through the roof during lockdown, into the club of “sustainable” investment options. The jury is still out on whether green initiatives and hunger for profits can go together, Ross says: “ESG funds are relatively new. A lot of the data doesn’t go back more than a few years, while most people invest for a period of 20 years or more.” There are benefits all round, she says, and an ESG-focused investment strategy is not harmful financially. “What studies have shown is that over the medium-term, they don’t seem to perform any worse.”

And yet, Ross acknowledges that investors are no tree-huggers. Profits matter. So what should green-minded investors do if they wish to do good, but make a buck too? One way, she suggests, is to put your chips on “best-in-class” options: firms that, albeit not perfect, are making the best effort in their sector to combat climate change. She singles out the energy company BP as a prominent example. Although still a net polluter, the firm is very popular among green funds, courtesy of its aggressive commitment to renewable energy. It is a pragmatic investment strategy, even if it often surprises unsuspecting investors, Ross says. “That really flummoxes people. Some say ‘hang on, that’s not what I signed up for.’ But just because of how the industry is, a lot of ESG funds will include companies that are ‘best-in-class’.”

Shifting standards

One reason why green-minded investors can find it hard to stick to a strategy is that there is no standard definition of what is green. The problem is no lack of relevant taxonomies, ratings or rankings, but their proliferation. What is an investor supposed to make out of obscure acronyms such as GRESB, UNPRI and SASB? “Τhe book is trying to help people navigate their way through all of that, because there are so many acronyms and promises. When you look at it, it doesn’t really mean anything,” Ross explains.

The day we spoke, Morningstar, a US data provider, announced that it would remove from its European sustainable investment list more than 1,200 funds, previously labelled as ESG-compliant. Its decision, according to Ross, was partly a response to a new EU taxonomy of green investments. At the end of the day, green investment remains a personal choice, based on each investor’s values and goals. “You still have to still do a lot of homework yourself, because the fund management industry is not making it easy for people right now.”

Woke corporations

Green finance is part of a broader movement pushing for a more responsible form of capitalism, often ridiculed by critics as hopelessly self-righteous, or “woke”. Large corporations are increasingly receptive to calls from shareholders, customers and employees for environmental or socially-oriented action. In 2020, Amazon’s Jeff Bezos pledged to donate $10bn to environmental causes, widely interpreted as a response to a letter signed by Amazon staff that criticised the firm’s efforts to reduce its carbon footprint.

The pandemic has offered a new lease of life to this movement. During lockdowns, activists unleashed brutal campaigns of naming and shaming companies laying off employees. Ross has been speaking to fund managers who have sold holdings in firms they felt were not addressing their concerns over how they treated workers. “Suddenly everyone thought that the ‘S’ in ESG was really important,” she says. “Some people will be very happy with owning a company that allows its workers to unionise and gives them great sick pay or maternity leave. But if you want to invest in the environment, it might not be your top priority.”

For ethical investors, divestment is becoming a popular pressure method. “Big fund managers are in a position to have meetings with board members,” Ross says. “A lot of these discussions happen behind the scenes in private meetings. Then, the board members will come out with some sort of commitment. Or they won’t, and the investors will warn them that they are going to vote against them, because fund managers themselves are often accountable to pension funds.” Positive engagement can be even more effective. In the book, Ross tells the story of Jenny Edwards, a retired civil servant who owned shares of large companies such as Shell and Marks & Spencer. Deeply concerned over her responsibility to future generations, she used her public speaking skills at shareholder meetings to convince these companies to change course. Cumulatively, small acts of kindness like this can make a big difference, Ross argues. Just a few months after Edwards had spoken at a Shell shareholder meeting, the firm announced its commitment to net zero emissions, despite financial pressures from the pandemic.

The pandemic’s green legacy

With energy prices hitting record levels, courtesy of the Russia-Ukraine war and post-pandemic blues, energy transition seems to be taking a back seat. And as the French government found out in 2018 with the rise of the Yellow Vest movement, carbon taxes can be massively unpopular. “In the past few months, governments have realised that the energy transition is not going to be smooth,” Ross says. “We need energy transition funds, net zero targets and companies to invest in renewable energy. But we also need protections in place for vulnerable members of society.”

Has the pandemic woken up investors to the dangers of inaction? Ross, who wrote much of the book during lockdown at her home in London with her two children out of school, thinks so: “The pandemic has changed investors’ perspective on things, insofar as you see how quickly change can happen,” she says. Oddly enough, its legacy might be positive, serving as a wake-up call for a much bigger challenge humanity faces. “We know that climate change is already here, and we know that it is going to get worse. But we don’t know how much worse, and companies need to prepare for that.”

About the author

Alice Ross, Deputy News Editor at the Financial Times is the author of Investing to Save The Planet: How Your Money Can Make a Difference

RECENT ARTICLES

-

Strong ESG records help firms take R&D global, study finds

Strong ESG records help firms take R&D global, study finds -

How residence and citizenship programmes strengthen national resilience

How residence and citizenship programmes strengthen national resilience -

Global leaders enter 2026 facing a defining climate choice

Global leaders enter 2026 facing a defining climate choice -

EU sustainability rules drive digital compliance push in Uzbekistan ahead of export change

EU sustainability rules drive digital compliance push in Uzbekistan ahead of export change -

China’s BYD overtakes Tesla as world’s largest electric car seller

China’s BYD overtakes Tesla as world’s largest electric car seller -

UK education group signs agreement to operate UN training centre network hub

UK education group signs agreement to operate UN training centre network hub -

Mycelium breakthrough shows there’s mush-room to grow in greener manufacturing

Mycelium breakthrough shows there’s mush-room to grow in greener manufacturing -

Oxford to host new annual youth climate summit on UN World Environment Day

Oxford to host new annual youth climate summit on UN World Environment Day -

Exclusive: Global United Nations delegates meet in London as GEDU sets out new cross-network sustainability plan

Exclusive: Global United Nations delegates meet in London as GEDU sets out new cross-network sustainability plan -

Fast fashion brands ‘greenwash’ shoppers with guilt-easing claims, study warns

Fast fashion brands ‘greenwash’ shoppers with guilt-easing claims, study warns -

Private sector set to overtake government as main driver of corporate sustainability in 2026, report suggests

Private sector set to overtake government as main driver of corporate sustainability in 2026, report suggests -

Sir Trevor McDonald honoured at UWI London Benefit Dinner celebrating Caribbean achievement

Sir Trevor McDonald honoured at UWI London Benefit Dinner celebrating Caribbean achievement -

Historic motorsport confronts its energy future

Historic motorsport confronts its energy future -

Protecting the world’s wild places: Dr Catherine Barnard on how local partnerships drive global conservation

Protecting the world’s wild places: Dr Catherine Barnard on how local partnerships drive global conservation -

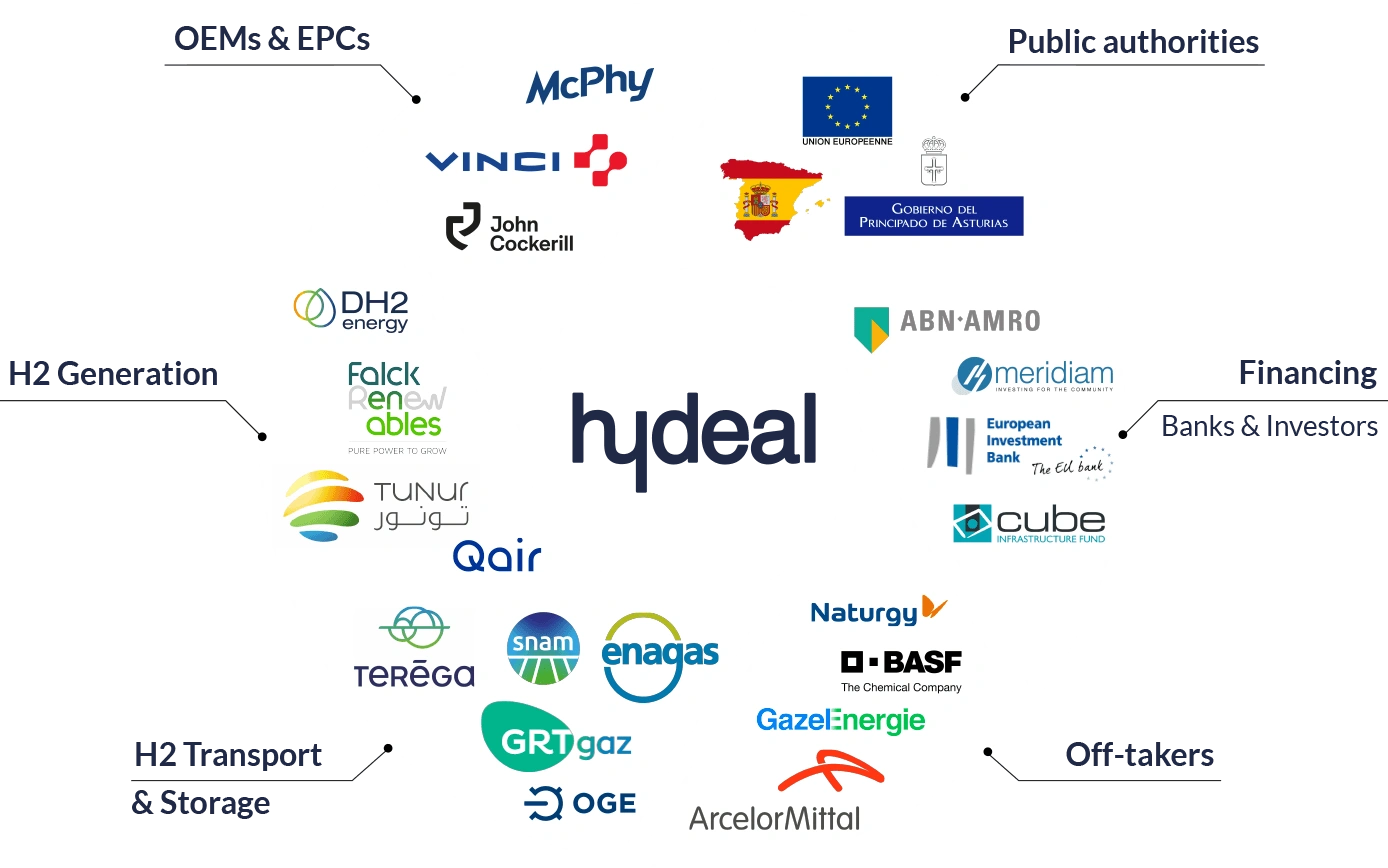

Europe’s HyDeal eyes Africa for low-cost hydrogen link to Europe

Europe’s HyDeal eyes Africa for low-cost hydrogen link to Europe -

Fabric of change

Fabric of change -

Courage in an uncertain world: how fashion builds resilience now

Courage in an uncertain world: how fashion builds resilience now -

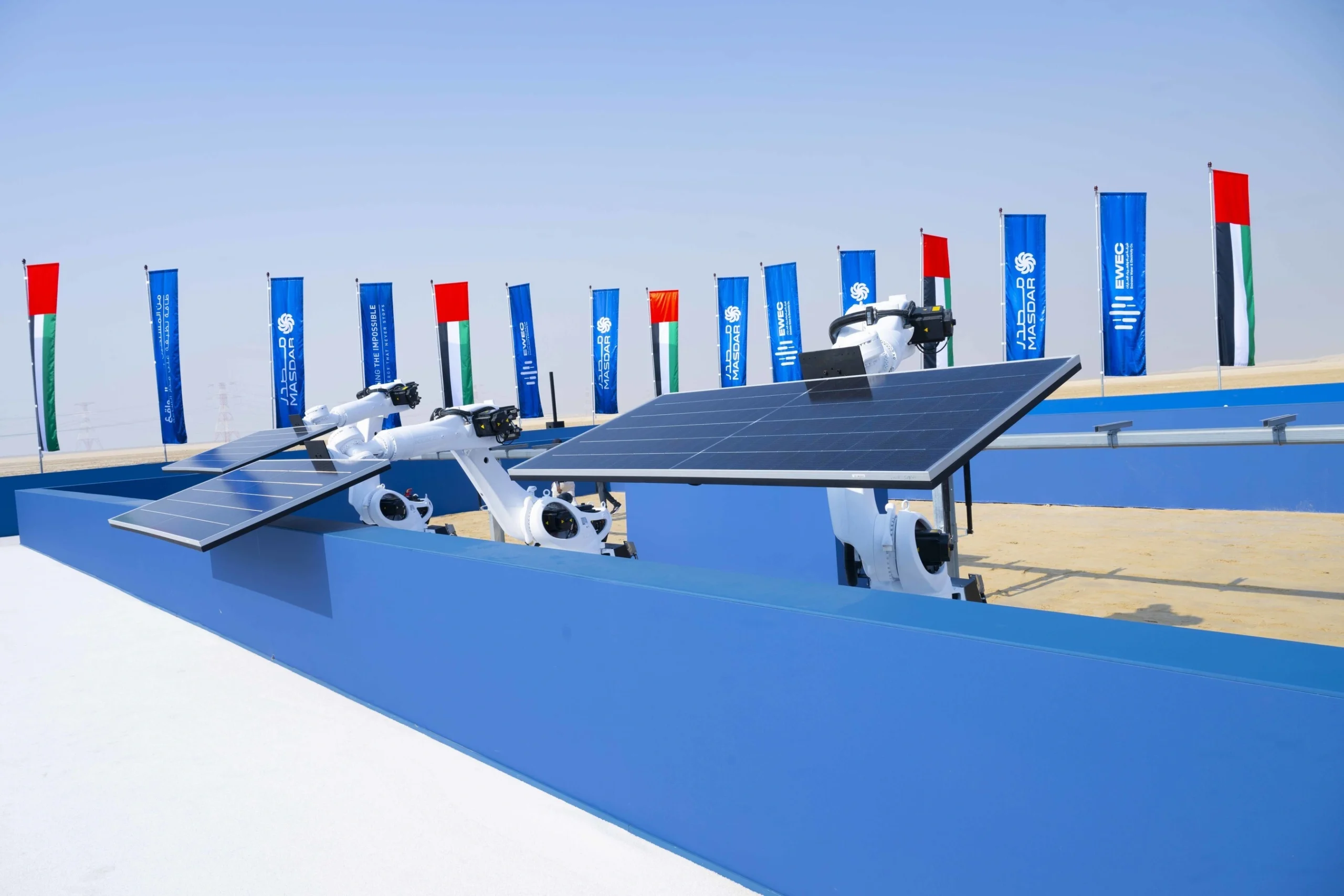

UAE breaks ground on world’s first 24-hour renewable power plant

UAE breaks ground on world’s first 24-hour renewable power plant -

China’s Yancheng sets a global benchmark for conservation and climate action

China’s Yancheng sets a global benchmark for conservation and climate action -

Inside Iceland’s green biotechnology revolution

Inside Iceland’s green biotechnology revolution -

Global development banks agree new priorities on finance, water security and private capital ahead of COP30

Global development banks agree new priorities on finance, water security and private capital ahead of COP30 -

UK organisations show rising net zero ambition despite financial pressures, new survey finds

UK organisations show rising net zero ambition despite financial pressures, new survey finds -

Gulf ESG efforts fail to link profit with sustainability, study shows

Gulf ESG efforts fail to link profit with sustainability, study shows -

Redress and UN network call for fashion industry to meet sustainability goals

Redress and UN network call for fashion industry to meet sustainability goals -

World Coastal Forum leaders warn of accelerating global ecosystem collapse

World Coastal Forum leaders warn of accelerating global ecosystem collapse