Unearthing the real dividing line in climate negotiations

John E. Kaye

- Published

- Home, Sustainability

Matthew Bell, Director of Frontier’s Public Policy explains how the real dividing line at COP26 is between those who think further adaptation is possible and those who do not

As the world converges on Glasgow, many unanswered questions remain. Will China’s President, Xi Jinping, attend COP26? Will climate finance pledges from wealthy nations reach US$100 billion? Will the Powering Past Coal Alliance succeed in getting agreements to stop construction of any more coal-fired electricity generation? These fundamental concerns, and others, appear to be the central talking points for COP26. Yet, they obscure the real dividing line in these negotiations.

The negotiators gathered in Glasgow will try to hammer out the next major step in the world’s response to climate change. They will seek to increase pledges to cut emissions, scale up financial assistance and “say it softly” to strengthen measures to adapt to climate change. These measures are vital in the role of adaptation – it is the real difference between those who are pushing for a faster or slower pace to reduce emissions.

Lines drawn in the sand

Almost everyone – even the most recalcitrant, although maybe not the most stubborn—now accepts that we are causing changes to the climate. Changes which have already resulted in conditions not witnessed in the history of human civilisation. Changes which, precisely because we have not experienced them before, will require us to alter buildings to make them liveable in hotter weather, move towns and cities that are too close to emerging flood plains, adjust supply chains and many other measures to adapt to a world that humans have never experienced.

The real dividing line at COP26 is between those who think further adaptation is possible – even if temperatures rise 2-3°C above pre-industrial levels – and those who do not. Those who think it is possible will argue against the more expensive and ambitious options to reduce emissions. Those who do not think the required levels of adaptation are possible – or that they are not desirable – will argue for more ambitious reductions in emissions.

Of course, neither side is likely to articulate their arguments in quite that way. Those in favour of tougher emissions reduction targets will point to the costs – human, financial, cultural – caused by higher temperatures. They will set out estimates of costs and will argue that the benefits from avoiding many of those make reducing emissions worthwhile. Those who argue against tougher targets will point to the same costs: the costs of acting and say they are too high in human, economic or cultural terms. But what the two sides are really saying is: adaptation is not possible or too expensive versus adaptation is possible and preferable.

However it is dressed up, once you accept that humans are causing climate change, governments with lower ambitions to reduce emissions are more confident their populations can adapt to the changes that will happen. Indeed, the people that vote for them are more confident of their ability to adapt. Governments that are more ambitious to reduce emissions believe the limits to adaptation will be reached earlier; and those who vote for them agree.

On a path to an ever-shifting environment

Adapting to climate impacts can take many forms. Some adaptation measures aim to return the environment, whether natural or constructed, to how it was before: re-wetting peatland, cooling existing buildings, staying put in your house but placing electric wiring and sockets half-way up the walls (in case of flooding), planting drought resistant crops. Other adaptation measures aim to preserve the outcome – mainly comfortable living conditions – while recognising it is not possible to return to an earlier state of affairs: abandoning a house in a flood plain in favour for one higher up the hill, fish species migrating further north in search of cooler water, harvesting some crops earlier in the season.

These adaptation options also cost money – just like action to reduce emissions – but who pays is different. Unlike much activity to reduce emissions, many of these costs are borne directly by households rather than through the tax system: flooding, the consequences of higher temperatures on productivity, changes in agricultural practices, and many others are felt first by the individual and only, sometimes, by government – just as they do to provide state-backed flood insurance. In contrast, measures to reduce emissions are faced first by government – through subsidising renewables and electric vehicles, paying to plant more trees. It is always tempting for governments – particularly facing large post-COVID debt – to avoid mitigation and the government spending it requires and, implicitly at least, favour adaptation.

Transparent discussions are the new terra incognita

While some may favour adaptation because it places more focus on individual choices and spending, others will point out that some changes are not reversible through any action to adapt: it is not possible to re-wet some dried-out peatland, it is not possible to re-create an extinct species, it will not be possible to reform the ice back in the Arctic or onto the glaciers which provide fresh drinking water to parts of Asia. The non-linearity of climate impacts and the existence of thresholds past which we cannot return places limits on many forms of adaptation. But knowledge of where those thresholds lie is still missing, we are only starting to understand what changes might be irreversible. Many will still think that humans can adapt to anything – particularly wealthier humans.

So whisper it softly: the real difference between those with high ambitions for COP26 and those with lower ambitions is their willingness to rely on adaptation. Once markets and governments can properly; understand the trade-offs, price them into markets, incorporate them into negotiating texts, and put them in the newspaper headlines, we will have a more transparent discussion about how to tackle climate change. We will also have a greater mandate to act on what has been agreed because any agreement will then “say it loudly” to explicitly acknowledge the proper role of mitigation and of adaptation.

For further information:

www.frontier-economics.com

This article is also featured in our Climate Change review, available to view here

RECENT ARTICLES

-

Strong ESG records help firms take R&D global, study finds

Strong ESG records help firms take R&D global, study finds -

How residence and citizenship programmes strengthen national resilience

How residence and citizenship programmes strengthen national resilience -

Global leaders enter 2026 facing a defining climate choice

Global leaders enter 2026 facing a defining climate choice -

EU sustainability rules drive digital compliance push in Uzbekistan ahead of export change

EU sustainability rules drive digital compliance push in Uzbekistan ahead of export change -

China’s BYD overtakes Tesla as world’s largest electric car seller

China’s BYD overtakes Tesla as world’s largest electric car seller -

UK education group signs agreement to operate UN training centre network hub

UK education group signs agreement to operate UN training centre network hub -

Mycelium breakthrough shows there’s mush-room to grow in greener manufacturing

Mycelium breakthrough shows there’s mush-room to grow in greener manufacturing -

Oxford to host new annual youth climate summit on UN World Environment Day

Oxford to host new annual youth climate summit on UN World Environment Day -

Exclusive: Global United Nations delegates meet in London as GEDU sets out new cross-network sustainability plan

Exclusive: Global United Nations delegates meet in London as GEDU sets out new cross-network sustainability plan -

Fast fashion brands ‘greenwash’ shoppers with guilt-easing claims, study warns

Fast fashion brands ‘greenwash’ shoppers with guilt-easing claims, study warns -

Private sector set to overtake government as main driver of corporate sustainability in 2026, report suggests

Private sector set to overtake government as main driver of corporate sustainability in 2026, report suggests -

Sir Trevor McDonald honoured at UWI London Benefit Dinner celebrating Caribbean achievement

Sir Trevor McDonald honoured at UWI London Benefit Dinner celebrating Caribbean achievement -

Historic motorsport confronts its energy future

Historic motorsport confronts its energy future -

Protecting the world’s wild places: Dr Catherine Barnard on how local partnerships drive global conservation

Protecting the world’s wild places: Dr Catherine Barnard on how local partnerships drive global conservation -

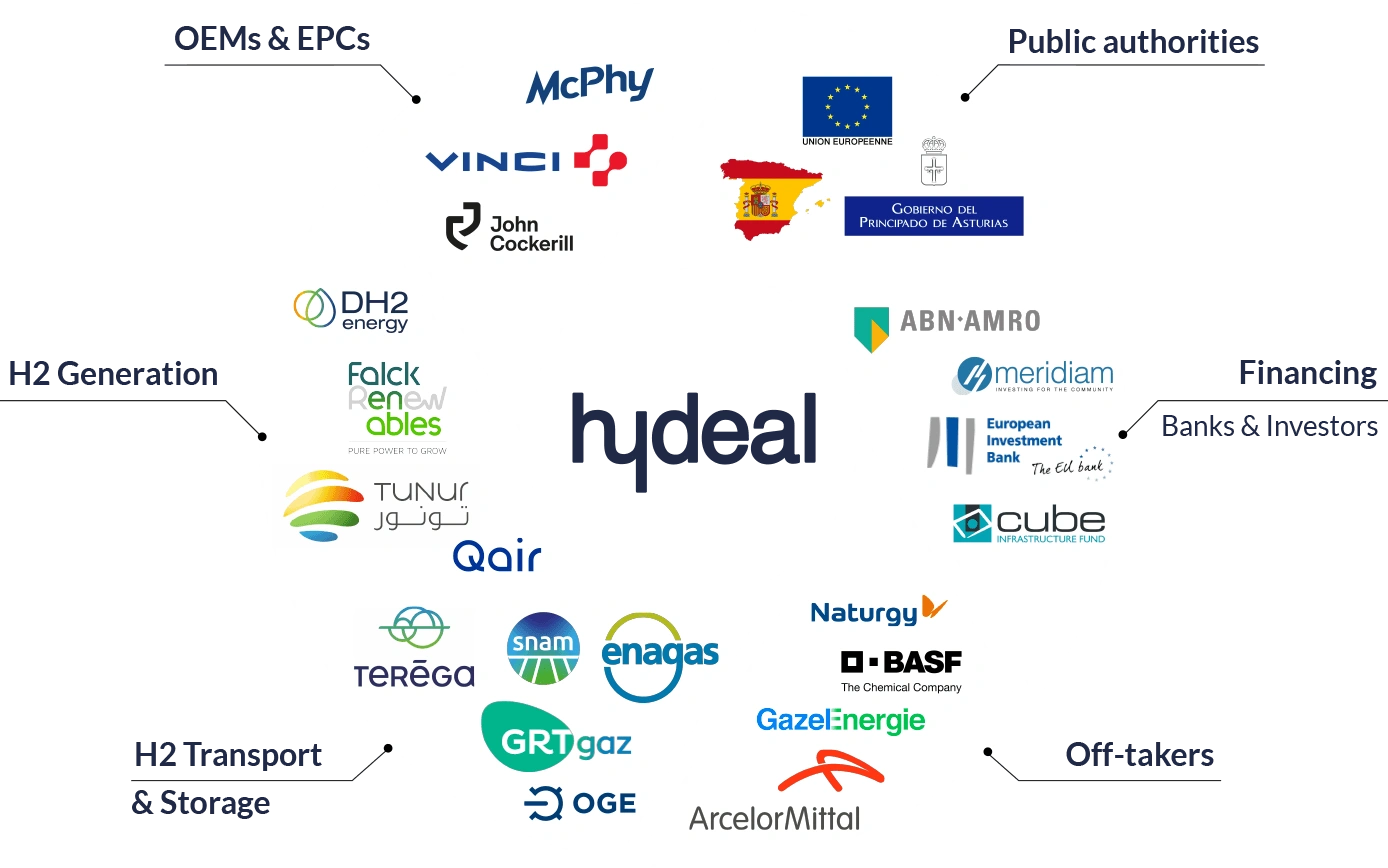

Europe’s HyDeal eyes Africa for low-cost hydrogen link to Europe

Europe’s HyDeal eyes Africa for low-cost hydrogen link to Europe -

Fabric of change

Fabric of change -

Courage in an uncertain world: how fashion builds resilience now

Courage in an uncertain world: how fashion builds resilience now -

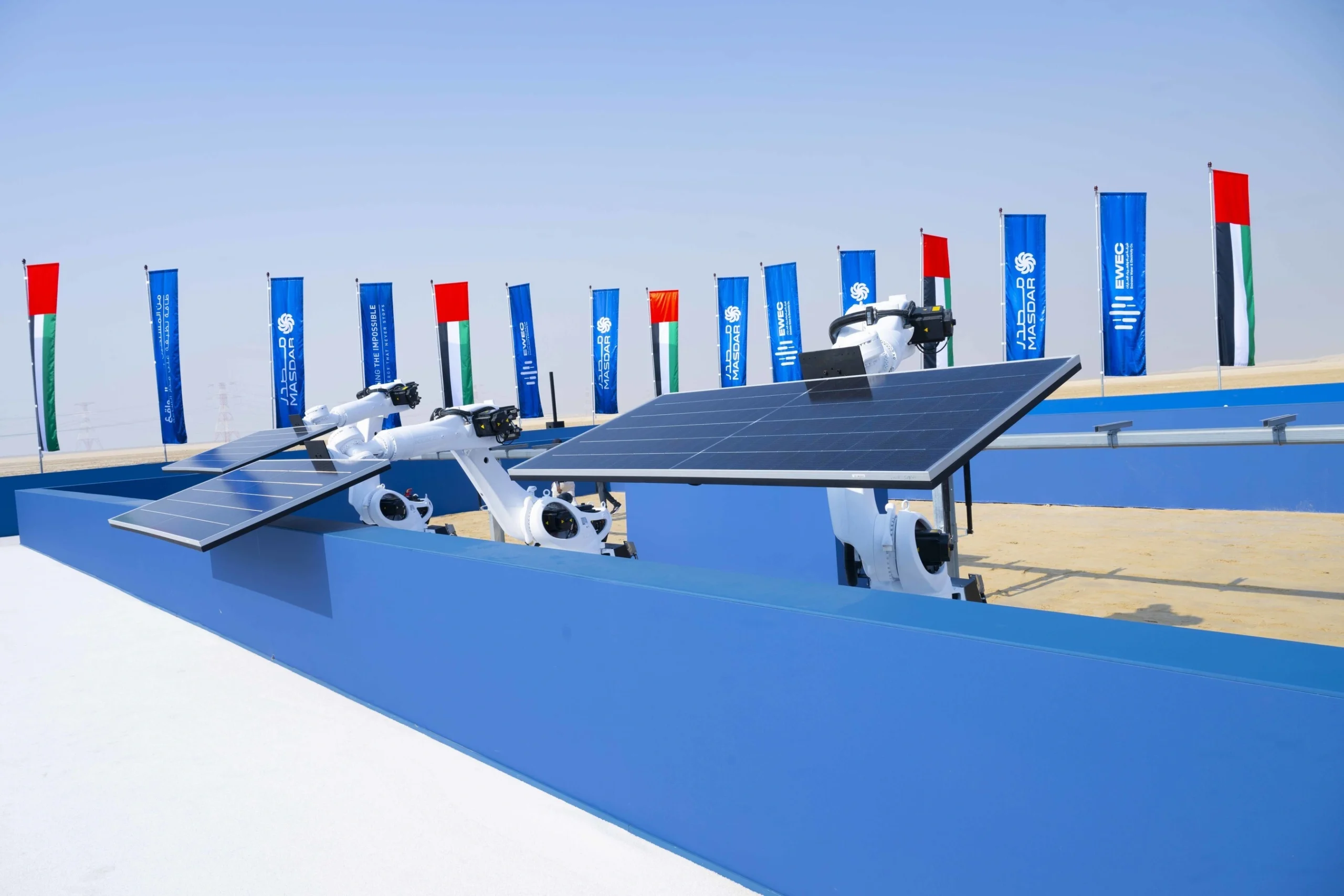

UAE breaks ground on world’s first 24-hour renewable power plant

UAE breaks ground on world’s first 24-hour renewable power plant -

China’s Yancheng sets a global benchmark for conservation and climate action

China’s Yancheng sets a global benchmark for conservation and climate action -

Inside Iceland’s green biotechnology revolution

Inside Iceland’s green biotechnology revolution -

Global development banks agree new priorities on finance, water security and private capital ahead of COP30

Global development banks agree new priorities on finance, water security and private capital ahead of COP30 -

UK organisations show rising net zero ambition despite financial pressures, new survey finds

UK organisations show rising net zero ambition despite financial pressures, new survey finds -

Gulf ESG efforts fail to link profit with sustainability, study shows

Gulf ESG efforts fail to link profit with sustainability, study shows -

Redress and UN network call for fashion industry to meet sustainability goals

Redress and UN network call for fashion industry to meet sustainability goals -

World Coastal Forum leaders warn of accelerating global ecosystem collapse

World Coastal Forum leaders warn of accelerating global ecosystem collapse