Why control freaks never build great companies

Andrew Horn

- Published

- Opinion & Analysis

The illusion of control has become management’s deadliest habit, breeding anxiety at the top and apathy below. Every collapsing culture begins with a boss who can’t let go, warns Andrew Horn

In corporate life, control is both a virtue and a vice. The ability to direct outcomes, align teams and impose order is visible proof of ‘leadership’. Yet the modern cult of control — reinforced by dashboards, KPIs and constant oversight — has reached pathological levels. It has produced managers who supervise every action but inspire none, and cultures where fear of failure has replaced the freedom to think.

According to recent research, almost four-in-five employees have experienced micromanagement. Nearly half say it made them unhappy at work, while over a third report being unable to cope with their workload.

Or, in other words, the tighter management’s grip, the less confidence people feel in exercising their own judgement.

A century before the age of metrics, the author Rudyard Kipling wrote If, a poem that every manager would do well to read. “If you can make one heap of all your winnings, and risk it on one turn of pitch and toss… and never breathe a word about your loss…” captures a temperament that remains the rarest of leadership qualities: composure.

Kipling’s line itself echoes an older source — the Bhagavad Gita, whose counsel to “treat alike happiness and distress, loss or gain, victory or defeat” defines the same ideal. Both describe what today’s psychologists call equanimity, or the ability to act decisively without the illusion of total control.

That illusion drives many leadership failures. The executive who believes that every variable can be managed begins to substitute activity for impact. Meetings multiply, delegation shrinks, and subordinates lose initiative. Over time, the organisation mirrors the mind of its leader: anxious, reactive, and brittle. True control — the only kind that lasts — is self-control.

The Sanskrit root of mantra literally means “protection of the mind.” In leadership terms, that is what reflection does: it insulates against distortion. A calm mind is a performance asset in that it helps leaders to pause, to separate emotion from decision, and to recognise limits. This in turn allows us to preserve proportion — the first casualty of stress.

Modern neuroscience reinforces what the ancients observed long ago. High cortisol levels impair risk assessment, memory, and empathy — the very traits most needed in a crisis. Leaders who cannot regulate themselves cannot stabilise others. Composure, then, is not indulgence but shrewd strategy in that it enables sound judgement under uncertainty, and protects organisations from the volatility of ego.

Micromanagement, by contrast, is ego made operational. It reflects the need to control others because one cannot control oneself. It creates dependency where autonomy should exist, and replaces accountability with compliance. The results are predictable: decision fatigue at the top, disengagement below, and a widening gap between effort and outcome.

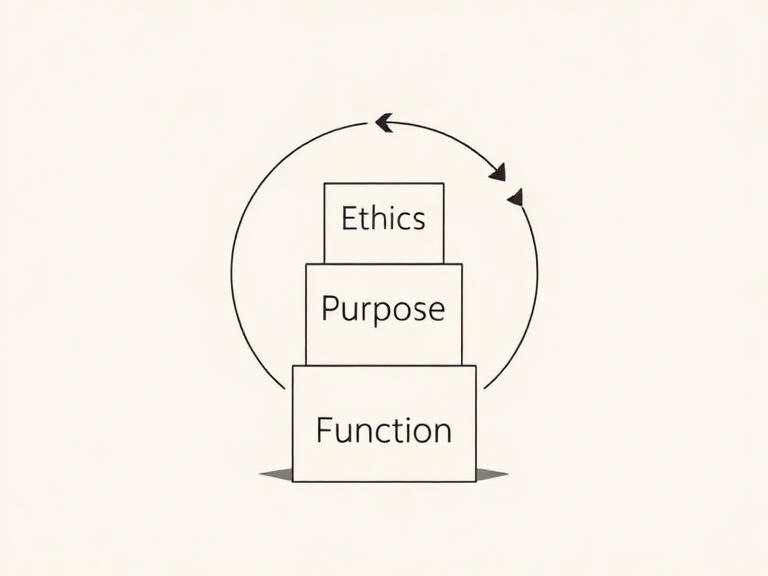

What distinguishes enduring leaders is their grasp of proportion. They know the difference between influence and interference. They set direction, not instruction; they monitor, but do not meddle. They understand, to borrow again from Sanskrit thought, that leadership is upadrashta — the overseer — and anumanta — the permitter. They enable others to act without abdicating responsibility.

This philosophy has practical implications for every boardroom. It means designing systems that assume trust rather than control: fewer approvals, shorter feedback loops, and open access to information. It means recognising that innovation flourishes not through oversight but through psychological safety. And it means accepting that uncertainty is the natural state of any enterprise attempting something new.

The corporate obsession with mastery — of markets, data, people — blinds us to a more durable truth that influence is finite and impermanence inevitable. The leader who accepts this recovers the only control that is ever real: mastery over themselves.

That is the genius of Rudyard Kipling’s If, and of the wisdom that preceded it. Success, whether in business or in life, depends less on power than on poise. The serenity to accept what cannot be mastered may yet prove the most strategic skill in a world that mistakes busyness for control.

Author Andrew Horn, the son of the great neuroscientist Sir Gabriel Horn and grandson of the socialist peer Baron Soper, is widely regarded as one of the world’s leading experts on traditional Indian and Sanskrit drama whose English translation of the epic 16th-Century Vidagdha Madhava by Rupa Goswami is considered the most accurate ever published. Despite his notable lineage, Andrew chose a different path, becoming a Hare Krishna monk for 20 years. During this time, he was given the name ‘Arjundas Adhikari’, signifying devotion to the hero Arjuna from the Mahabharata. He also appeared on Top of the Pops with Boy George for the singer’s 1991 hit, Bow Down Mister.

READ MORE: ‘These are the skills that separate leaders who thrive from those who don’t’. Adapting to new conditions is a core business skill. Here, our health and wellbeing correspondent Andrew Horn explains how professionals can approach uncertainty with focus and confidence. Drawing on strategic insight, workplace trends and timeless philosophy, he outlines five practical steps to manage change, sustain performance and turn disruption into progress

Do you have news to share or expertise to contribute? The European welcomes insights from business leaders and sector specialists. Get in touch with our editorial team to find out more.

Main image: Yan Krukau/Pexels

Sign up to The European Newsletter

RECENT ARTICLES

-

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world -

Will Trump’s Davos speech still destroy NATO?

Will Trump’s Davos speech still destroy NATO? -

Philosophers cautioned against formalising human intuition. AI is trying to do exactly that

Philosophers cautioned against formalising human intuition. AI is trying to do exactly that -

Life’s lottery and the economics of poverty

Life’s lottery and the economics of poverty -

On a wing and a prayer: the reality of medical repatriation

On a wing and a prayer: the reality of medical repatriation -

Ai&E: the chatbot ‘GP’ has arrived — and it operates outside the law

Ai&E: the chatbot ‘GP’ has arrived — and it operates outside the law -

Keir Starmer, Wes Streeting and the Government’s silence: disabled people are still waiting

Keir Starmer, Wes Streeting and the Government’s silence: disabled people are still waiting -

The fight for Greenland begins…again

The fight for Greenland begins…again -

Failure is how serious careers in 2026 will be shaped

Failure is how serious careers in 2026 will be shaped -

Poland’s ambitious plans to power its economic transformation

Poland’s ambitious plans to power its economic transformation -

Europe’s space ambitions are stuck in political orbit

Europe’s space ambitions are stuck in political orbit -

New Year, same question: will I be able to leave the house today?

New Year, same question: will I be able to leave the house today? -

A New Year wake-up call on water safety

A New Year wake-up call on water safety -

The digital euro is coming — and Europe should be afraid of what comes with it

The digital euro is coming — and Europe should be afraid of what comes with it -

Make boards legally liable for cyber attacks, security chief warns

Make boards legally liable for cyber attacks, security chief warns -

Why Greece’s recovery depends on deeper EU economic integration

Why Greece’s recovery depends on deeper EU economic integration -

Why social media bans won’t save our kids

Why social media bans won’t save our kids -

This one digital glitch is pushing disabled people to breaking point

This one digital glitch is pushing disabled people to breaking point -

Japan’s heavy metal-loving Prime Minister is redefining what power looks like

Japan’s heavy metal-loving Prime Minister is redefining what power looks like -

Why every system fails without a moral baseline

Why every system fails without a moral baseline -

The many lives of Professor Michael Atar

The many lives of Professor Michael Atar -

Britain is finally having its nuclear moment - and it’s about time

Britain is finally having its nuclear moment - and it’s about time -

Forget ‘quality time’ — this is what children will actually remember

Forget ‘quality time’ — this is what children will actually remember -

Shelf-made men: why publishing still favours the well-connected

Shelf-made men: why publishing still favours the well-connected -

European investors with $4tn AUM set their sights on disrupting America’s tech dominance

European investors with $4tn AUM set their sights on disrupting America’s tech dominance