Come together for better business

John E. Kaye

- Published

- Home, Sustainability

With people’s finances coming under as much pressure as the environment, Marcelo Vieta and George Cheney explore whether worker cooperatives are the answer

The pandemic brought to the surface, and in some cases exacerbated, long-standing crises. The so-called “great resignation” revealed the disaffection with working life for more and more people. The heightened health risks faced by essential workers, while some of us were able to shelter at home, underscored the marginalising effects of our economic system, including dimensions of race and class. At the same time, the climate enjoyed a bit of breather from incessant economic activity in the first months of lockdown, clearly reminding us of the perils of untethered human production and accumulation on the global ecosystem, as well as the links of some viruses to habitat destruction.

Hidden in plain sight are existing organisations present in most economic sectors around the world that are custom-made to address these crises and make for better working conditions: worker cooperatives (WCs). WCs are companies collectively owned and democratically controlled by workers themselves.

This is why we open our book, Cooperatives at Work with a chapter entitled “Crisis and Opportunities.” In one of our many case studies, “Guerilla Translation”, a Spanish P2P translation and communications co-operative, says: “The crisis is a killer, but also a muse…”

The interrelated economic, social, political, and environmental crises of our age make less-hierarchical and highly participatory organisations like WCs all the more relevant and urgent. For us, worker co-ops approach an ideal work organisation. They thrive during crises better than many conventional firms because of their ownership and governance forms. Collective property and democratic decision-making are central to them. These structures make them strong and firmly rooted in their local communities, less likely to pick up shop and move elsewhere. Their economic and social forms of democracy also make them more agile and more organisationally resilient.

Part of the bigger picture

Cooperatives can’t do it alone, however. We recognise that worker-owned-and-governed co-ops need to be considered in a matrix with other organisation types, including the labour movement, mutual aid initiatives, and the social and solidarity economy. We see WCs as one important realisation of economic democracy and social equity, certainly not as isolated organisational or business forms.

To take one of the book’s cases of co-operatives in the plural economy, the Kola Nut Collaborative facilitates the creation of multiple organisational forms throughout Chicago: time banking, needs and offers exchanges, mutual aid projects, and worker cooperatives, all centred on self-organisation at the neighbourhood level. Which form is used depends on the context, the people involved, and their needs and goals.

We argue that by principle and design, worker cooperatives are well suited to pursue organisational and business paths that can be transformational, even revolutionary. Nurturing democratic economic organisations such as worker co-ops is becoming increasingly essential, we argue, for the long-term survival of humanity and the biosphere. One way WCs flourish is by working within networks of solidarity with other co-ops and related organisations. Examples of these networks around the world include: Canadian-based Black Women Professional Workers’ Co-op, Italy’s Fuorimercato or Emilia Romagna’s dense cooperative economy, the Basque Country’s Mondragón Corporation of co-operatives, Latin America’s Comparte network, the US’s Industrial Commons, and many more.

WCs are also resilient because they are less hierarchical and more equitable in how they design work and share in the business’ returns. Democracy helps give them a coherent, principled legal framework: WCs represent a statute-based democratic work arrangement. As a result, worker co-ops are designed for maximising diversity, equity, inclusion, and justice (DEIJ). Cooperation Jackson, in Jackson Mississippi, fosters social and solidarity networks and creates local wellbeing infrastructures based on community/solidarity economics and DEIJ values.

Transformational

Worker co-ops are transformational for not only for organisations but also for workers’ lives and for their communities. Through business conversions to cooperatives, employees of firms facing ownership succession issues can create democratic and solidarity-based organisations out of formerly hierarchical ones. Examples are Argentina’s empresas recuperadas, Chicago’s New Era Windows, and Italy’s Marcora Law worker buyouts. Some of these even open up their shop floors to the community to use as other spaces of care and social production beyond the daily business of the co-op. In Argentina, for instance, many of these “worker-recuperated companies” include initiatives such as popular high school equivalency programmes, community recreation centres, and free neighbourhood medical clinics.

Co-ops are often innovative. But in the mainstream, the association of innovation with co-ops is not a familiar one because of the unfounded stereotypes about cooperators lacking business sense and because of real barriers to co-ops’ participation in the established arena of small-business development. Yet, there is much evidence for how worker cooperatives, in particular, innovate in traditional and in new, targeted ways, such as creating dynamic horizontal communication systems at work.

In the traditional sense, WCs are often leaders in their fields. For example, the URSSA construction cooperative in the Mondragon group built the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao. Worker cooperatives are also versatile business forms for adopting and adapting technologies in new ways. Distributed Co-operative Organizations (DisCOs), for instance, are

a form of platform cooperative that ethically deploys communication and networking technologies for making connections and doing work across distances via copyleft and open-source protocols. In doing so, they are bringing back notions of “the commons” – spaces and practices owned by no-one but open for many to use and collaborate to get things done.

Creating stronger communities

Worker co-ops are notably innovative by doing business in ways that embrace more equitable labour-management relations. femPROCOMUNS (or “We Make Commons”), based in Catalunya, Spain, is a consultancy multi-stakeholder cooperative that subdivides its work into “Cooperativized Activity Groups,” or CAGs, along four “commons criteria”:

– For everyone (accessible, shared, replicable);

– Produced by everyone (everyone contributes or can contribute to them);

– Sustainable (not exhausting resources/reproduction/fair relationships);

– Managed by everyone (everyone participates or can participate in governance).

Worker-owners in worker co-ops tend to be more secure than non-cooperative workers, in jobs with dignity, longevity, and solidarity. This is in part because a worker co-op member can be said to wear four hats at the same time – owners, workers, patrons, and community members. These enable the building of strong relationships internal and external to the co-op, helping bridge the two common forms of community: relational and territorial.

They help to make for stronger communities, too, witnessed in the high human development indicators in places where they are found aplenty, as in Preston, UK; the Emilia Romagna region of Italy; in the Basque Country; in Kerala, India; in South Korea; and in other parts of the world. They contribute to more secure communities, tackling some of the most pressing issues of our age collectively.

Take, for instance, Manchester, UK’s Unicorn Grocery, practicing a deep form of community while promoting a more sustainable food system founded on the principles of food sovereignty and sociocracy. At Unicorn Grocery, this means strategic decisions are made democratically and based on accessibility to good food sourced ethically, considerations of the environmental impact of transportation and packaging, and the labour practices of the producers and manufacturers. Different “circles of community” ensure this, including: geographic (most of the shoppers live within a two-mile radius); food systems (solidarity with organic/fair trade networks); solidarity economies (actively supporting the development of new cooperatives) and connections to global food sovereignty (networking with initiatives that are working towards more just and equitable food systems).

An overarching issue today is climate change. Much more needs to be done to fully internalise ecological principles in organisations and pursue practices to reshape the economy. WCs such as femPROCOMUNS and Unicorn Grocery could be at the leading edge of designing organisations with the ecology firmly top of mind.

Consider another such worker co-op: Earthworker Cooperative out of Australia’s Latrobe Value. Earthworker, set up as a co-op incubator that also facilitates converting business to co-ops, spearheads a promising network of co-ops attempting to tackle the climate crisis via renewable energy and sustainable industrial and technological practices while creating good green jobs. Dave Kerin, a founder of the co-op with a labour and construction background, insists that we move from “protest to production” in renewable energy and other fields because we are running out of time. A general assembly is scheduled for all of the Earthworker cooperatives with a vision to help foster similar co-op-focused networks in other countries.

Another promising worker co-op tackling environmental justice issues and designed along sociocracy principles is Vancouver, Canada’s Sustainability Solutions Group. Practicing deep ecology both internally and externally, SSG is a consulting firm for organisations, cities and regions. It is a great example of recursive organising with specific cooperative and solidarity values that privilege collaborative work and privilege inclusivity, such as its adoption of a nearly flat wage scale.

Through these and dozens of other cases, Cooperatives at Work shows how worker cooperatives are part of “the organisational imagination” needed to re-envision economic possibilities along more inclusive, more equitable, and more ecologically sound directions. It is time we began taking seriously the cooperative possibilities at work and in our communities. Given our current age of intertwined global crises, we have nothing to lose by trying.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

Marcelo Vieta (left) and George Cheney, along with four colleagues, are co-authors of ‘Cooperatives at Work’ in the ‘Future of Work’ series from Emerald Publishing, UK.

RECENT ARTICLES

-

Strong ESG records help firms take R&D global, study finds

Strong ESG records help firms take R&D global, study finds -

How residence and citizenship programmes strengthen national resilience

How residence and citizenship programmes strengthen national resilience -

Global leaders enter 2026 facing a defining climate choice

Global leaders enter 2026 facing a defining climate choice -

EU sustainability rules drive digital compliance push in Uzbekistan ahead of export change

EU sustainability rules drive digital compliance push in Uzbekistan ahead of export change -

China’s BYD overtakes Tesla as world’s largest electric car seller

China’s BYD overtakes Tesla as world’s largest electric car seller -

UK education group signs agreement to operate UN training centre network hub

UK education group signs agreement to operate UN training centre network hub -

Mycelium breakthrough shows there’s mush-room to grow in greener manufacturing

Mycelium breakthrough shows there’s mush-room to grow in greener manufacturing -

Oxford to host new annual youth climate summit on UN World Environment Day

Oxford to host new annual youth climate summit on UN World Environment Day -

Exclusive: Global United Nations delegates meet in London as GEDU sets out new cross-network sustainability plan

Exclusive: Global United Nations delegates meet in London as GEDU sets out new cross-network sustainability plan -

Fast fashion brands ‘greenwash’ shoppers with guilt-easing claims, study warns

Fast fashion brands ‘greenwash’ shoppers with guilt-easing claims, study warns -

Private sector set to overtake government as main driver of corporate sustainability in 2026, report suggests

Private sector set to overtake government as main driver of corporate sustainability in 2026, report suggests -

Sir Trevor McDonald honoured at UWI London Benefit Dinner celebrating Caribbean achievement

Sir Trevor McDonald honoured at UWI London Benefit Dinner celebrating Caribbean achievement -

Historic motorsport confronts its energy future

Historic motorsport confronts its energy future -

Protecting the world’s wild places: Dr Catherine Barnard on how local partnerships drive global conservation

Protecting the world’s wild places: Dr Catherine Barnard on how local partnerships drive global conservation -

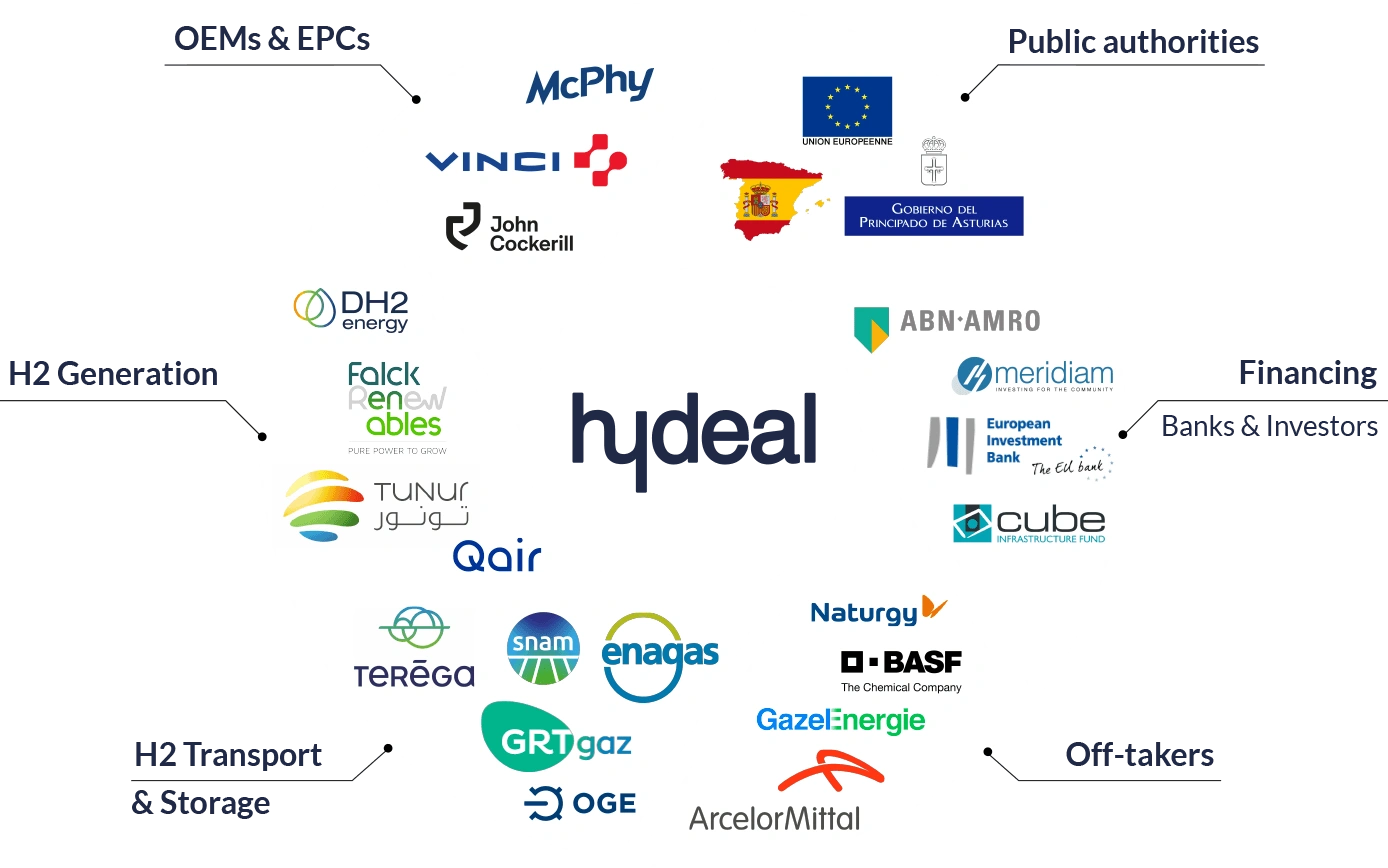

Europe’s HyDeal eyes Africa for low-cost hydrogen link to Europe

Europe’s HyDeal eyes Africa for low-cost hydrogen link to Europe -

Fabric of change

Fabric of change -

Courage in an uncertain world: how fashion builds resilience now

Courage in an uncertain world: how fashion builds resilience now -

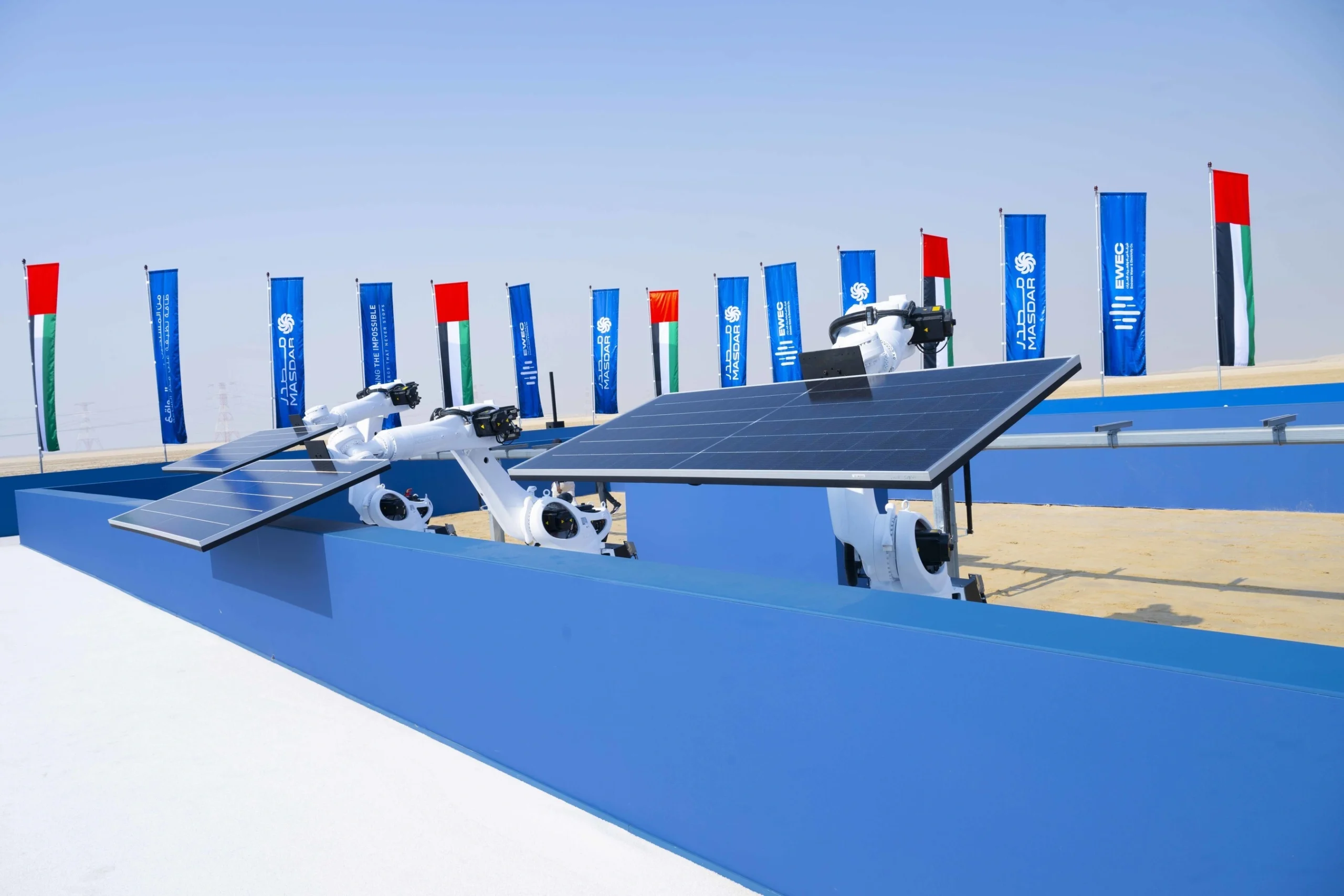

UAE breaks ground on world’s first 24-hour renewable power plant

UAE breaks ground on world’s first 24-hour renewable power plant -

China’s Yancheng sets a global benchmark for conservation and climate action

China’s Yancheng sets a global benchmark for conservation and climate action -

Inside Iceland’s green biotechnology revolution

Inside Iceland’s green biotechnology revolution -

Global development banks agree new priorities on finance, water security and private capital ahead of COP30

Global development banks agree new priorities on finance, water security and private capital ahead of COP30 -

UK organisations show rising net zero ambition despite financial pressures, new survey finds

UK organisations show rising net zero ambition despite financial pressures, new survey finds -

Gulf ESG efforts fail to link profit with sustainability, study shows

Gulf ESG efforts fail to link profit with sustainability, study shows -

Redress and UN network call for fashion industry to meet sustainability goals

Redress and UN network call for fashion industry to meet sustainability goals -

World Coastal Forum leaders warn of accelerating global ecosystem collapse

World Coastal Forum leaders warn of accelerating global ecosystem collapse