Memories of Tehran, a city of contrasts

Oggy Boytchev

- Published

- Travel and Lifestyle

Oggy Boytchev, former BBC World Affairs producer and long-time colleague of John Simpson, was one of the few Western journalists to report from inside Iran during a critical period in the country’s history. He recently spoke about that experience on Simpson’s BBC Radio 4 podcast, Dictators. With Iran once again in crisis, he looks back on his time in Tehran — a city marked by fear, beauty and contradiction — and wonders if he will ever go back, this time simply as a tourist

It takes at least an hour by taxi from Tehran’s new Imam Khomeini Airport to reach the centre of the Iranian capital. As you approach the city limits, the golden dome of the Tomb of Imam Khomeini looms on the right-hand side, surrounded by four minaret spears.

In Ayatollah Khomeini’s 1979 revolution, arguably as much as ten per cent of the population took an active part, compared to barely one per cent in the Russian Revolution of 1917. Historical accounts suggest many of those participants perpetrated despicable violence on their fellow countrymen. I met one of them a decade and a half ago. He was 45 at the time and a gentle, doting father. But as a weedy sixteen-year-old back in 1979, he had volunteered to be one of Ayatollah Khomeini’s bodyguards. He survived the front line of the brutal Iran–Iraq war, and later fought in Bosnia, Chechnya and Lebanon. His greatest wish, he told me, was to send his young son to school in Britain. I often wonder if he did.

When you reach the city limits, the old Mehrabad Airport lies to your left. If your driver is used to showing tourists the sights, he’ll take a left turn, and the full glory of the Azadi Tower, the symbol of Tehran, will unfold before your eyes.

It’s hard not to be impressed by its scale. Built in 1971 as part of the extravagant celebrations for the 2,500th anniversary of the Persian Empire, it was designed to perpetuate the glory of the last Shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi. Originally named the Shahyad Tower (The Royal Tower), it was renamed the Azadi Tower, or ‘The Freedom Tower’, after the revolution.

From a distance, it looks as if it’s been carved from a single piece of white marble. Like the Eiffel Tower, it gives an impression of lightness. Its four foundation pillars resemble delicate birds’ wings, which evolve elegantly into an octagonal tower — the octagon being a universal symbol of balance and harmony.

If you choose to stay in downtown Tehran, the Laleh Hotel is your best bet. A 1960s structure with nods to Le Corbusier’s functional design, it was originally built as the Intercontinental Hotel. From a distance, it resembles an elegant cigarette box. In the lobby, huge crystal chandeliers sparkle. Men in black suits lounge on large leather sofas, quietly scanning visitors from their vantage points.

In all Iranian hotels, you must leave your passport at reception. You’ll only get it back when you check out.

If you get a room on one of the higher floors facing north, you can enjoy the magnificent view of the Alborz Mountains, which seem so close you could almost touch them. However, when I last stayed there in 2009, the hotel had seen better days. The swimming pool hadn’t worked in years. The carpets in the long, dark corridors were soaked in cigarette smoke, mixed with the whiff of blocked drains. The rooms were badly in need of redecoration. The bathroom tiles had been painted over with white acrylic paint, which was peeling off. There was a stain in the corner of the ceiling. But the bed linen smelled fresh. I’ll always associate that particular mixture of smells with Tehran.

Another abiding memory of Tehran was fear — the butterflies in your stomach that you might be arrested at any moment on trumped-up charges. In every security briefing before travelling to Iran, I was told: Don’t sign any fabricated confessions, even if it means long sleepless nights in prison. A more benign fear was that each visit might be my last. Getting an Iranian visa, especially as a journalist, has always been hit and miss.

I first travelled to Iran in 2005 for the presidential election that brought Mahmoud Ahmadinejad to power. The vote went to a second round, as the first was inconclusive. My visa was extended, and I spent a few weeks there. It was the end of the more liberal, reformist phase in Iran’s recent history. I was invited to parties in North Tehran — the wealthy, middle-class part of the city — that rivalled the wild gatherings in North London, where I lived at the time. Ahmadinejad turned the clock back.

I remember breakfast at the Laleh Hotel being an appalling experience. Middle-aged waiters in stained black suits wandered the dining room without urgency, begrudgingly clearing dirty plates. I usually had a piece of soft Iranian cheese, a few slices of fresh tomato and cucumber, and vast amounts of tea. Takeaways are always the better option in Tehran. I’d recommend the chelo kebab — lamb neck fillet, steamed basmati rice with a crispy saffron crust, and grilled tomato. Wash it down with doogh, a yoghurt drink seasoned with salt and mint.

If you tire of the Laleh, there’s always the Esteghlal Hotel on the northern edge of the city. As you approach the hills of North Tehran, you leave behind the austerity of downtown and enter a different world. Here, Islamic dogma didn’t apply to people’s clothes. In a token nod to tradition, women wore their scarves loosely draped at the backs of their heads. Heavy make-up and top Western fashion were the norm. The houses are modern, most of them built to the latest anti-earthquake specifications. Tehran lies on a fault line and has suffered devastation in the past. The air is cleaner, and the Alborz Mountains seem even closer.

The Esteghlal (meaning ‘Independence’) Hotel must have been the place to be seen in the 1960s, when it opened as the Royal Tehran Hilton. What struck me most when I first entered wasn’t the spacious marble lobby or the big windows overlooking a large garden, but the disproportionate number of men in black suits milling about. I had been warned this was one of the most closely monitored places in Tehran. Every room was said to be bugged. The hotel consists of two interconnected towers, joined by the reception lobby. It has both indoor and outdoor swimming pools and boasts clay tennis courts. A third tower is currently under construction. Breakfast at the Esteghlal was a much better experience with more fresh fruit, especially my favourite: sweet watermelon.

I haven’t returned to Iran since the ‘Green Revolution’ in June 2009, when people took to the streets to protest what they saw as stolen elections. Newsgathering became a criminal offence. My visa was revoked, and I’ve not been able to obtain another. I miss the excitement of my time in Iran. But I also miss walking around Tajrish Square in North Tehran, with its designer shops. I miss drinking pomegranate juice in trendy, Western-style cafés with my Iranian friends. I miss trips to Darband, just north of Tajrish, with its amazing restaurants. I miss buying pickled walnuts from the street vendors or ordering ‘Bulgarian kebab’ — lamb chops skewered on a long sword. I’m not sure why they call it ‘Bulgarian’; I’ve never seen it in Bulgaria.

Oggy Boytchev is a celebrated former BBC journalist and producer who has covered the majority of international conflicts over the last 30 years, often with the BBC’s World Affairs Editor, John Simpson. His critically-acclaimed book Simpson & I lifts the lid on the untold stories behind the headlines and documents some of the most memorable reports to appear on BBC News. Today, Oggy is an in-demand public speaker and author. His latest novel, Bullion – The Mystery of Gaddafi’s Gold, is an adventure spy thriller based on research into Gaddafi’s missing wealth.

RECENT ARTICLES

-

Air India and Lufthansa expand codeshare to nearly 100 routes across Europe and India

Air India and Lufthansa expand codeshare to nearly 100 routes across Europe and India -

These European hotels have just been named Five-Star in Forbes Travel Guide’s 2026 awards

These European hotels have just been named Five-Star in Forbes Travel Guide’s 2026 awards -

Wingsuit skydivers blast through world’s tallest hotel at 124mph in Dubai stunt

Wingsuit skydivers blast through world’s tallest hotel at 124mph in Dubai stunt -

Royal Ascot leads the field in sport and style

Royal Ascot leads the field in sport and style -

Slovenia launches digital nomad visa for non-EU remote workers

Slovenia launches digital nomad visa for non-EU remote workers -

Charting confidence at sea with the St. Kitts & Nevis Ship Registry

Charting confidence at sea with the St. Kitts & Nevis Ship Registry -

Luxury travel market set to more than double by 2035 as older, wealthier travellers drive demand

Luxury travel market set to more than double by 2035 as older, wealthier travellers drive demand -

Countdown to Davos 2026 as Switzerland gears up for the most heated talks in years

Countdown to Davos 2026 as Switzerland gears up for the most heated talks in years -

Prague positions itself as Central Europe’s rising MICE powerhouse

Prague positions itself as Central Europe’s rising MICE powerhouse -

Bleisure boom turning Gen Z work travel into ‘life upgrade’

Bleisure boom turning Gen Z work travel into ‘life upgrade’ -

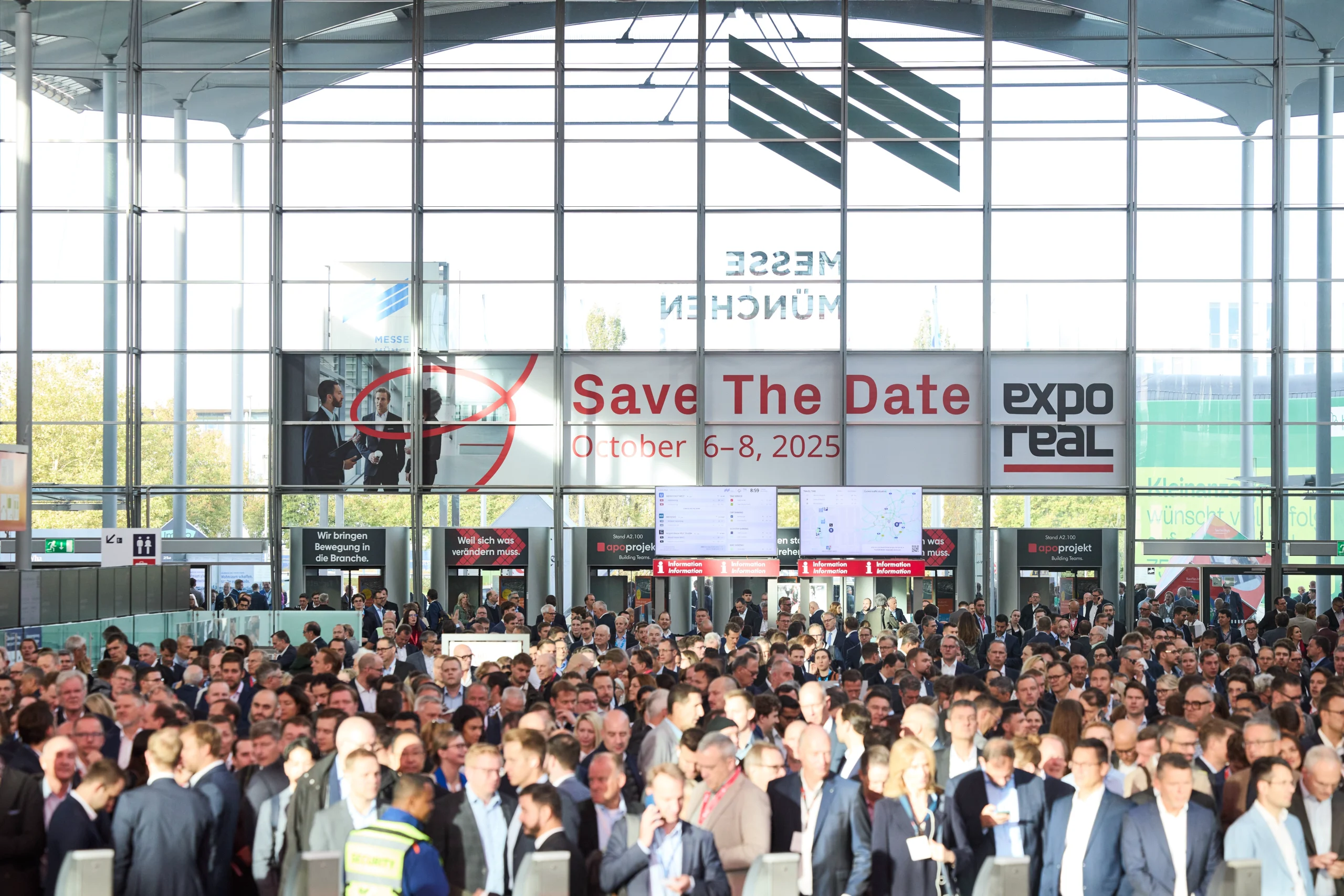

Europe’s property market shows fragile recovery as EXPO REAL survey highlights housing demand and policy strain

Europe’s property market shows fragile recovery as EXPO REAL survey highlights housing demand and policy strain -

Inside London’s £1bn super-hotel with £20k penthouses, private butlers and a gilded eagle

Inside London’s £1bn super-hotel with £20k penthouses, private butlers and a gilded eagle -

The five superyacht shows that matter most

The five superyacht shows that matter most -

A world in gold: Andersen Genève launches the Communication 45

A world in gold: Andersen Genève launches the Communication 45 -

Uber plots Channel Tunnel disruption with app-bookable high-speed trains

Uber plots Channel Tunnel disruption with app-bookable high-speed trains -

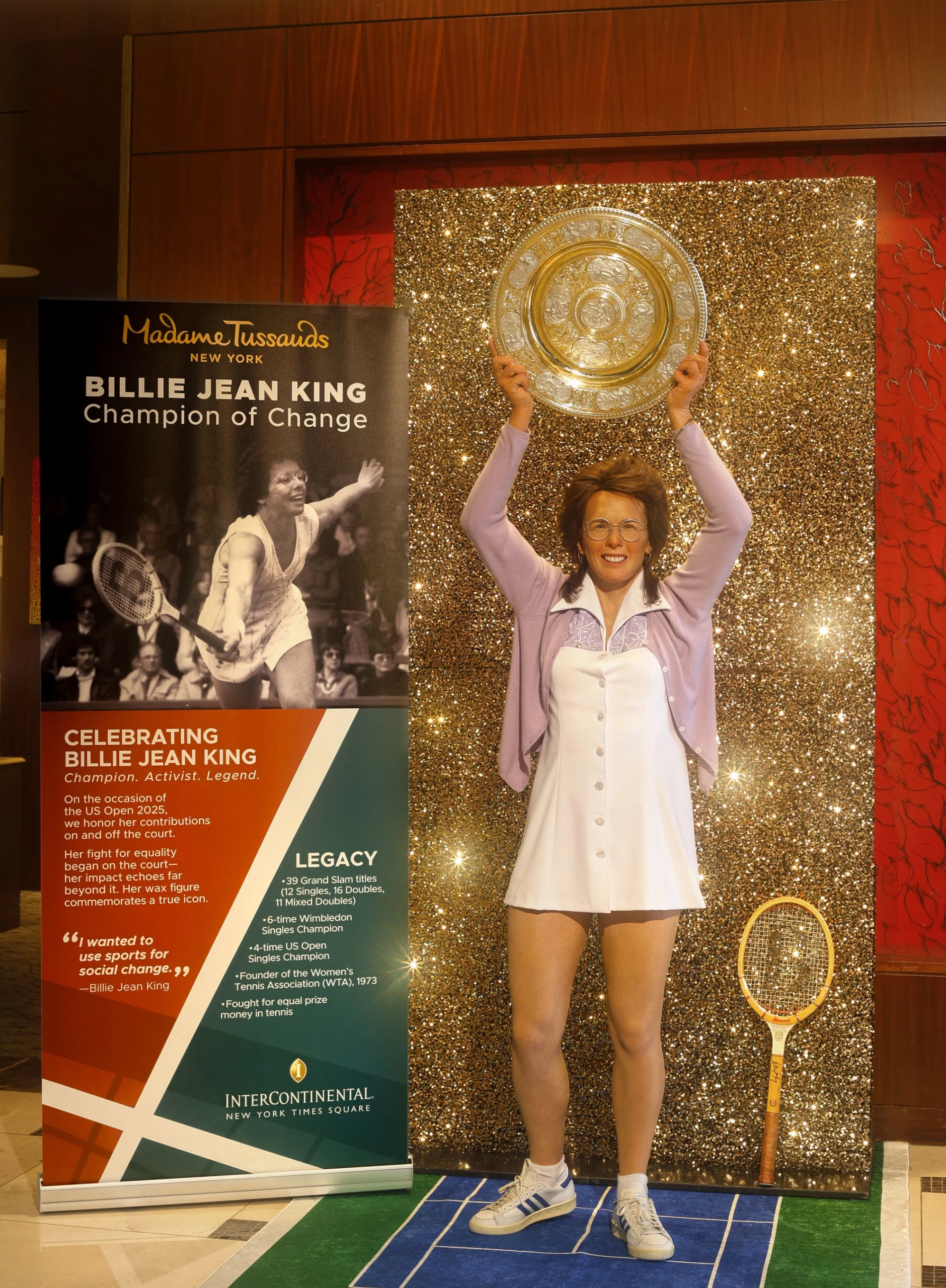

Game, set...wax. Billie Jean King statue unveiled in New York

Game, set...wax. Billie Jean King statue unveiled in New York -

How a tiny Black Forest village became a global watchmaking powerhouse

How a tiny Black Forest village became a global watchmaking powerhouse -

Memories of Tehran, a city of contrasts

Memories of Tehran, a city of contrasts -

Addiction rehab and recovery at Hope Thailand

Addiction rehab and recovery at Hope Thailand -

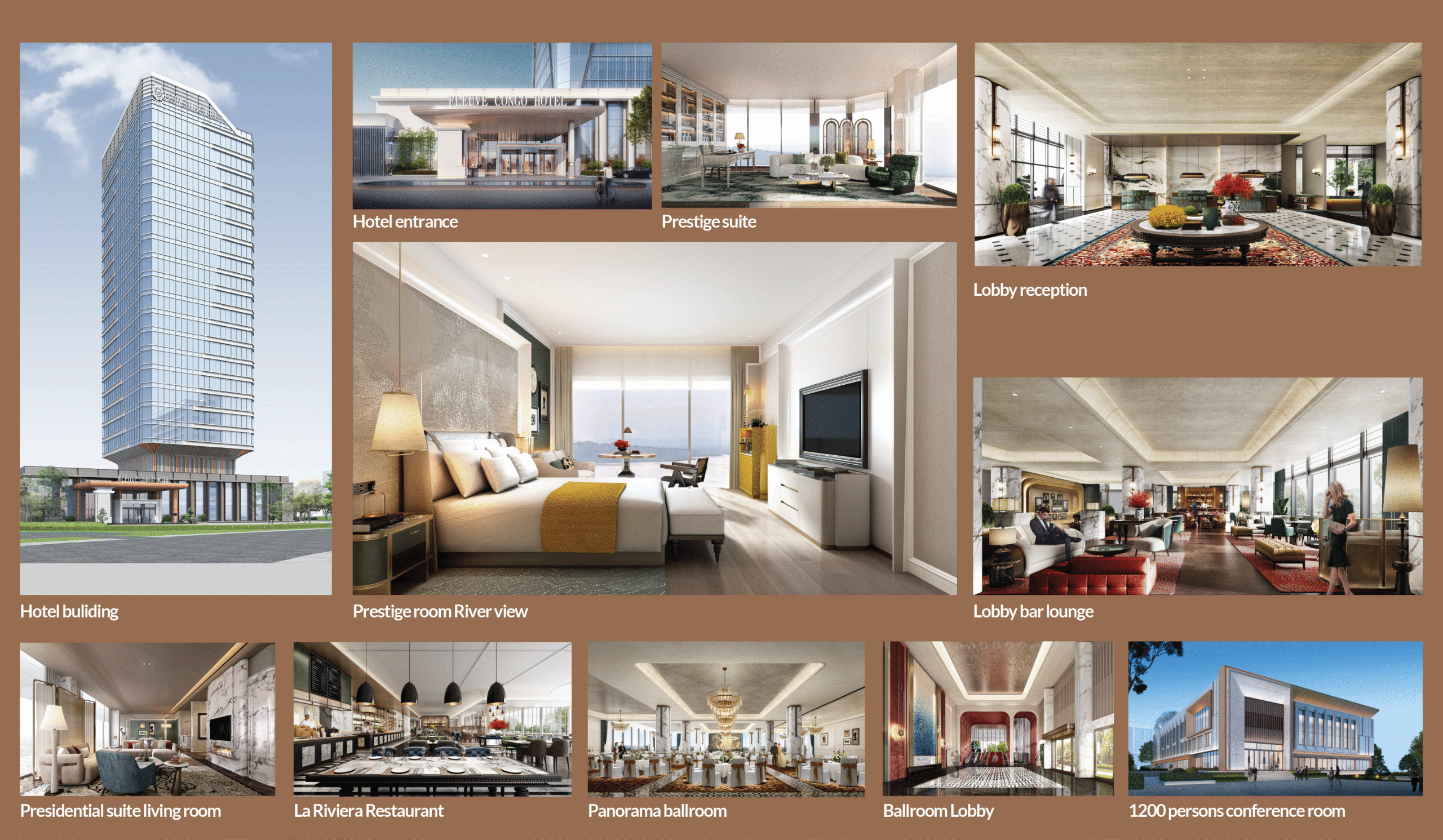

Capital gains: inside Kinshasa’s flagship five-star hotel

Capital gains: inside Kinshasa’s flagship five-star hotel -

This under-the-radar spot is Europe’s best late summer escape

This under-the-radar spot is Europe’s best late summer escape -

Why Madeira is Europe’s ultimate island retreat

Why Madeira is Europe’s ultimate island retreat -

Three resorts, three generations, and one extraordinary family legacy

Three resorts, three generations, and one extraordinary family legacy -

Wellness with a view at Cape of Senses

Wellness with a view at Cape of Senses -

Travel across five European countries by train in under one day

Travel across five European countries by train in under one day