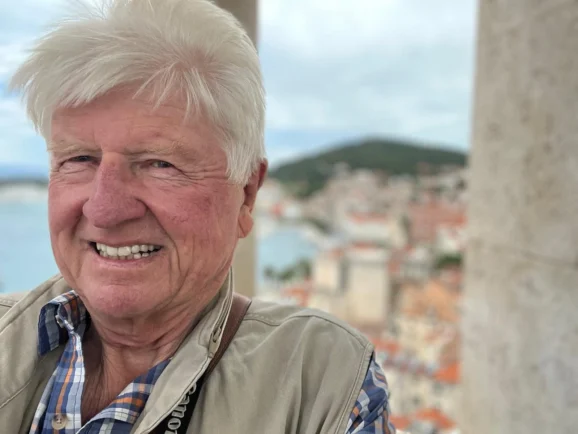

Stanley Johnson discovers the Mediterranean’s best-kept secret

John E. Kaye

- Published

- Business Travel, Opinion & Analysis

With its Roman ruins, Venetian elegance and Europe’s cleanest coastal waters, Croatia’s stunning Dalmatian coast is one of the Mediterranean’s last truly unspoilt escapes. From Diocletian’s Palace in Split to the pine-shaded coves of Hvar and the cliffs of Telašćica, our Editor-at-Large Stanley Johnson journeys through a region of remarkable history and dazzling natural beauty — and reflects on the political and personal ties that bind it to Europe

When my wife, Jenny, and I arrived in Split, Croatia’s second-largest city, one evening last week, we were welcomed warmly by a well-dressed young concierge who introduced himself as Petar.

“Petar, not Peter?” I asked.

“Yes, Petar,” he replied. “Actually, my full name is Petar Krešimir. My parents named me after Petar Krešimir IV, Croatia’s most famous king. He reigned from 1059 until his death in 1074. How long are you here for? Perhaps I can brief you fully after you’ve seen your room.”

Well, the room was superb — a fifth-floor corner room with a view to die for over the harbour and the islands beyond.

Petar Krešimir’s briefing, too, was just what we needed. We sat around a table in the foyer. We were all ears. This young man clearly knew his onions. Context is everything.

“As you may know,” Petar began, “many Roman emperors – the so-called Illyrian Emperors – came from this region. Emperor Diocletian was one of them. He was born in the year 284, in Salona, not far from here. He spent the last twenty years of his life here. Diocletian’s Palace is now a World Heritage site.”

Petar spread a map on the table. He explained that, if Roman rule was one of the key factors in the region’s story, so too was Croatia’s location at the western fringe of another once-great empire: the Ottoman Empire.

“The Battle of Sinj in 1715, for example” – he pointed to the map – “was one of the key moments in world history. If we hadn’t driven back the Ottomans at Sinj, they could have advanced to Venice and beyond, and the whole face of the Western world would have been different.”

Food for thought, indeed.

We arrived at Diocletian’s Palace early the next day. In medieval times the vast area occupied by the palace evolved into a whole mini-city, with shops and houses, stalls and markets. Diocletian’s tomb was converted into one of the world’s smallest cathedrals.

While Jenny tried to decipher the Latin inscriptions inside the dome, I climbed up the narrow stone staircase to the bell tower. What a vantage point! As I stood there, I could look down at the walls and roofs of the palace. I also had a panoramic view of Split harbour. A gigantic P&O cruise ship, dwarfing a hundred other vessels of every size and shape, was nosing its way into its mooring.

Our time in Split coincided with some brilliant early summer weather. The quayside promenade was not yet packed with visitors, but already an infinite variety of refreshments was on offer. You can spend €10 on a pizza at a stall on the quay, or upwards of €100 per head on a fish dinner at some upmarket restaurant with a view of the Adriatic.

On our last day we bought return tickets on a catamaran to Hvar. We headed out to sea, bypassing Brač — a large island with splendid, much-frequented sandy beaches which lies opposite Split — before, an hour or so later, we reached Hvar.

Hvar, the town, has the same name as the island. In the early 15th century, it became the wealthiest town in Dalmatia, when Venice ruled this part of the coast, with all ships to and from that ‘pearl of the Adriatic’ stopping there.

Hvar’s main square is a jewel of Venetian architecture — a good place to sit and reflect on events which have made Croatia the unique country it is today, including, of course, its entry — in 2013 — into the European Union.

A few days before our visit to Split, my wife and I had a chance to visit Telašćica National Park, situated at the northern end of the Kornati archipelago. We hiked around a saltwater lake, linked in some mysterious way to the nearby ocean, but without any visible surface connection.

Later, we climbed to the top of Croatia’s biggest cliffs, rising dramatically 180 metres out of the sea.

A sign indicated that the Telašćica National Park was a Natura 2000 site and that Croatia, as a member of the European Union, was proud to be part of that network — which, thirty years earlier, as an official of the European Commission, I had helped create.

As I sat there that morning in Hvar’s idyllic main square, enjoying a local beer, I felt a sudden twinge of nostalgia.

How to Visit Split, Hvar and Croatia’s Dalmatian Coast

Croatia’s Dalmatian coast runs along the eastern Adriatic, stretching roughly from Zadar in the north to Dubrovnik in the south. Split and the island of Hvar sit at its heart, surrounded by a constellation of other islands including Brač, Vis and Korčula. The region is famous for its coastal cities, World Heritage sites, and more than 1,200 islands, islets and reefs.

How to Get There

- Split:

Split Airport (SPU) is around 24km from the city centre — about 40 minutes by taxi or shuttle. It has direct flights from London, Manchester, Dublin and most major European cities, especially during the summer season. Ferries and fast catamarans depart regularly from Split harbour to nearby islands. - Hvar:

There’s no airport on Hvar. Most travellers reach the island by catamaran (1 hour) or ferry (up to 2 hours) from Split. Ferries arrive at Stari Grad; catamarans dock in Hvar Town itself.

Where to Stay

- In Split:

Boutique hotels and heritage apartments are tucked into Diocletian’s Palace and the Old Town. Larger seafront resorts and modern hotels line the coast west of the city centre. - In Hvar Town:

Expect elegant harbourside hotels, stone guesthouses, and a handful of upscale beach clubs. For quieter options, consider Stari Grad or inland villages like Velo Grablje.

What to See

- Split:

- Diocletian’s Palace – A Roman imperial residence turned living city; now a UNESCO World Heritage site.

- Cathedral of St Domnius – Formerly Diocletian’s mausoleum; one of the oldest cathedrals in the world still in use.

- Riva Promenade – A busy waterfront strip ideal for cafés and people-watching.

- Marjan Hill – A forested peninsula with walking trails and spectacular city views.

- Hvar:

- Hvar Town Square (Pjaca) – The largest square in Dalmatia, overlooked by a 16th-century cathedral.

- Fortica Fortress – A hilltop fort with sweeping views of the harbour and Pakleni Islands.

- Dubovica Beach – A picture-perfect pebbled cove 8km east of town.

- Pakleni Islands – A cluster of small islands, just 10–20 minutes by water taxi from Hvar Town.

Top Beaches Nearby

- Zlatni Rat (Golden Horn), Brač – A shapeshifting spit of white pebbles and turquoise water; ideal for windsurfing and sunbathing.

- Murvica Beach, Brač – Quieter and more rustic than Zlatni Rat, with views of Vidova Gora and shaded spots under the pines.

- Punta Rata, Brela – A Blue Flag beach with pine forests and the iconic Brela Stone rising from the sea.

- Stiniva Bay, Vis – A hidden, cliff-framed cove accessible by boat or steep path; voted one of Europe’s best beaches.

- Stončica Beach, Vis – Family-friendly, with shallow clear waters, woods for shade, and a laid-back beach bar.

- Dubovica, Hvar – Small but striking, set beside a 17th-century stone house and reached via a short hike.

- Velika Duba, Makarska Riviera – Remote, pebbled and peaceful, surrounded by pine forest and known for its sunsets.

When to Go

- High Season (July–August):

Hot, busy, and festive, with fully open ferries, tours and nightlife. Best for swimmers and socialites. - Shoulder Season (May–June, September):

Warm weather, fewer crowds, and better prices. Most island services still running. - Low Season (October–April):

Quiet and atmospheric on the mainland, but many island ferries, restaurants and hotels close or reduce hours.

What to Eat and Drink

- Dalmatian cuisine is Mediterranean with a Croatian twist:

- Grilled fish and octopus

- Pasticada (beef stewed in wine)

- Black risotto (crni rižot)

- Pag cheese and Hvar lavender honey

- Local olive oil and sea salt

- Wines: Plavac Mali (red), Pošip and Grk (white)

- Where to eat:

From no-frills konobas (taverns) to fine dining on hotel terraces, Dalmatia caters for all palates — and budgets.

Sea Quality and Sustainability

Croatia’s coastal waters were ranked #1 in Europe for cleanliness in 2023, according to the European Environment Agency, which tested more than 22,000 sites across the EU.

Out of nearly 900 Croatian beaches, over 99% earned ‘excellent’ status — thanks to low industrial pollution and a lack of overdevelopment. Many are part of the Natura 2000 protected network, including Telašćica cliffs and lakes.

Did You Know? The Truth Behind 101 Dalmatians

The iconic spotted breed is named after Dalmatia — the region of Croatia where similar dogs were once bred as carriage escorts and guard dogs. References to the “Canis Dalmaticus” date back to the 17th century. The breed gained global fame with Dodie Smith’s novel The Hundred and One Dalmatians (1956), but its name remains tied to the sunlit shores of southern Croatia.

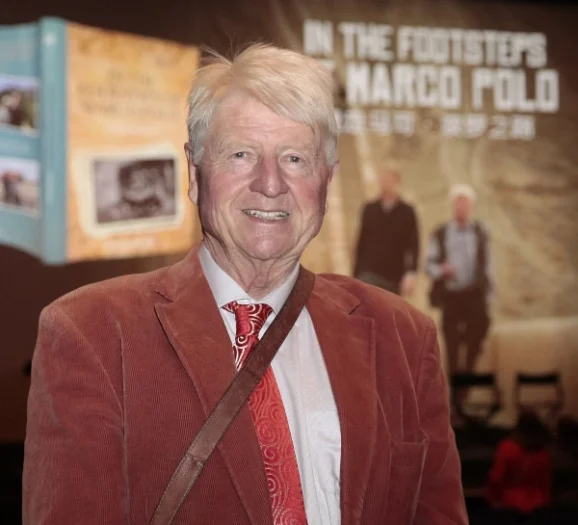

Stanley Johnson is a leading environmentalist, award-winning author and former Member of the European Parliament (MEP). Father of former UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson, Stanley has helped shape major environmental policies in Europe and championed global conservation efforts. He remains a powerful voice on sustainability, climate change and international affairs. He is also a distinguished and prolific author, with more than 20 books to his name spanning environmental protection and global conservation, fiction, and memoir. His latest novel, satirical political thriller Kompromat, has been critically acclaimed by the national press.

Main picture: Split, Croatia’s second-largest city, seen from the harbour — where Roman emperors once ruled, Venetian traders passed through, and today’s travellers set off by catamaran to explore the islands, after wandering the ruins of Diocletian’s Palace and the pine-fringed promenade. Photo: Vladimir Srajber

RECENT ARTICLES

-

Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes

Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes -

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others -

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again -

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart?

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart? -

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing -

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage -

The limits of good intentions in public policy

The limits of good intentions in public policy -

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament?

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament? -

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth -

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours -

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality -

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now -

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day -

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy -

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it -

What if he falls?

What if he falls? -

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world -

Will Trump’s Davos speech still destroy NATO?

Will Trump’s Davos speech still destroy NATO? -

Philosophers cautioned against formalising human intuition. AI is trying to do exactly that

Philosophers cautioned against formalising human intuition. AI is trying to do exactly that -

Life’s lottery and the economics of poverty

Life’s lottery and the economics of poverty -

On a wing and a prayer: the reality of medical repatriation

On a wing and a prayer: the reality of medical repatriation -

Ai&E: the chatbot ‘GP’ has arrived — and it operates outside the law

Ai&E: the chatbot ‘GP’ has arrived — and it operates outside the law -

Keir Starmer, Wes Streeting and the Government’s silence: disabled people are still waiting

Keir Starmer, Wes Streeting and the Government’s silence: disabled people are still waiting -

The fight for Greenland begins…again

The fight for Greenland begins…again -

Failure is how serious careers in 2026 will be shaped

Failure is how serious careers in 2026 will be shaped