Welcome to the machine

John E. Kaye

- Published

- Home, Technology

SpeedFactory

Five years ago researchers at Manz AG, a German engineering company, came up with an idea. Using a technique called ‘fiber patch placement’, they built bicycle saddles fitting the shape of the cyclist’s backside. Instead of relying on one-size-fits-all designs, a laser would cut the saddle based on the cyclist’s body specifications.

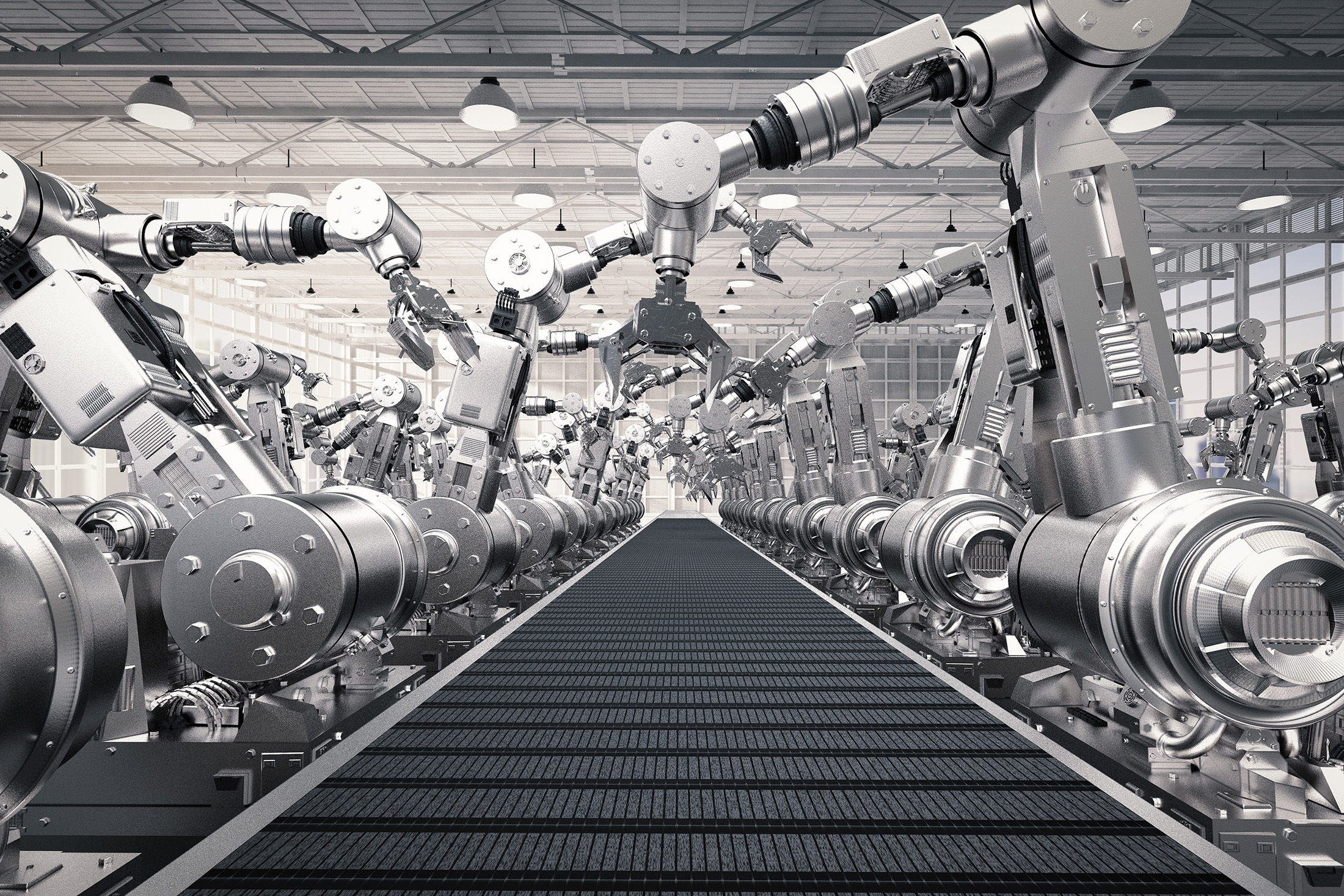

“We never thought that this would be a real market,” says Axel Bartmann, a spokesperson for Manz. But a demonstration of the technique in an exhibition caught the eye of sportswear manufacturer Adidas. That was the beginning of a beautiful friendship between the two companies. In autumn 2016, with a little help from Manz, Adidas launched its first ‘Speedfactory’ – a new type of industrial plant where robots take centre stage.

The Speedfactory concept turns the traditional supply chain on its head. Instead of shipping in ready-made components to be assembled in the factory, robots use basic raw materials to produce trainers layer by layer. Additive manufacturing (also known as 3D printing), as this production technique is called, along with computer-assisted knitting and laser cutting, reduce raw material loss to a minimum and increase precision. The first Speedfactory has been set up in Ansbach, Bavaria, and is expected to produce its first pair of trainers in mid-2017. Adidas has another one in Atlanta in the pipeline and hopes to replicate this model elsewhere.

The smart factory

The Speedfactory is part of a revolution that is reshaping manufacturing. Benefitting from a combination of technological developments, including artificial intelligence (AI), the Internet of Things (IoT) and big data, manufacturers are building ‘smart factories’ where robots work hand-in-hand with workers.

Germany and the US are pioneers in this new industrial revolution, but other countries are gradually catching up. Chinese manufacturers will be buying around 40% of all industrial robots sold globally by 2019, according to an analysis by the International Federation of Robotics (IFR).

One reason why robots are on the rise is that they are finally cheap. Boston Consulting Group, a US consultancy, forecasts that industrial robots will be cheaper by 20% over the next ten years, while improving their productive capabilities by 5% annually. In 2015 they performed 10% of manufacturing activities that a machine is able to perform, expected to rise to 25% by 2025.

Automation may help Europe and the US address a pressing economic and political challenge: de-industrialisation. Adidas is a case in point. As most sportswear companies, the German multinational has built global supply chains, tapping into cheap manual labour in Asia for production and keeping crucial design and R&D functions closer to home. As Asian labour costs are gradually rising and technology becomes cheaper, ‘onshoring’ production back to Europe, makes more sense. This is a trend that extends far beyond the sportswear industry. “With fully automated production lines, you can bring back production where it used to be, Europe or the US, and also to the place where the product is used,” says Manz’s Axel Bartmann.

Automation follows the old business axiom: customer is king. With the rise of e-commerce, customers have at their disposal a variety of options and expect swift delivery. Global supply chains have struggled to meet demand. It often takes several months between the conception of a product and its delivery to retailers. Shipping from Asia to Europe and America is costly too. “With automated production lines you have all the advantages of local production. You don’t need to order two million yellow shoes in different sizes from the Far East, wait for a year to get them delivered and then realise that yellow is not the right colour. This is a problem facing companies today: production is not flexible and it is far away from the market. People are not willing to wait three months until they get their smartphone or T-shirt. If you need a product in Berlin, making it in Munich is better than making it in Bangladesh,” says Bartmann.

This is also the rationale behind the Speedfactory. “With the Adidas Speedfactory, we break with conventions and set a new status quo for the sporting goods sector. Gone are the days of long lead times, products and materials that had to be shipped across continents and the concept of a centralised, conventional production. It is time to find answers on how, where and why products are made,” says Katja Schreiber, a spokeswoman for Adidas.

Can robots revolt?

The new industrial revolution requires a higher level of connectivity between robots, as well as an increasing amount of data stored on the cloud. However, many manufacturers still hesitate to have factory supply chains connected online, for fear of being hacked. Nine out of ten US manufacturers are worried about cyber attacks, according to a report by BDO USA, an accounting company. Manufacturing was also the second most frequently targeted industry for cyber attacks in 2015, according to a report by IBM.

“Until recently, security was not very high on the agenda of people working in the manufacturing sector. But it becomes a more important issue as information becomes more transparent and visible and many manufacturers have global operations and collaborate with other firms. One solution is to have physical security layers, so that people have to authenticate their identity physically. But it is also useful to have a software layer too, such as multiple firewalls. Security is a journey rather than a single event,” said Thomas Donato, President of EMEA at Rockwell Automation, the world’s leading provider of industrial automation services.

A common threat is ‘ransomware’ software, which penetrates factory systems and blocks access to crucial programmes or data in order to blackmail the owner. Last year, hackers attacked robots used at a plant in Mexico, blocking access to files necessary to operate the assembly line. Attacks of this type can be very effective in low-margin industries where time is money.

Another fear is that robots could physically harm workers, inadvertently or after a cyber attack. “Workers will have to learn how to collaborate with robots. They will not ever behave as humans do, but may come close to this. Although safety standards are improving, robots can always hurt people. It is not dangerous working with them, but it is definitely a different feeling,” said Dr Anselm Blocher, a senior researcher at the German Research Center for Artificial Intelligence (DFKI) who studies the collaboration between people and robots in industrial settings.

The automation conundrum

Automation awakens old fears reminiscent of the original Industrial Revolution. Will machines deprive ordinary folk of secure, well-paid jobs? Many fear so. A study published in January by the McKinsey Global Institute forecasts that robots could replace humans in half of current job positions by 2055, although the pace of automation might be slow.

But rage against the machine might be premature, believes Dr Blocher: “There is no danger that there will be no work for humans at factories over the next three decades, because some of the most crucial tasks cannot be performed by robots. When you have standardised processes like welding a straight line robots are very good, maybe better than humans. But if you have to weld in a position that is difficult to reach, humans are better.”

Thomas Donato, President of EMEA at Rockwell AutomationAutomation might even render work more creative, says his colleague at DFKI, Dr Tim Schwartz: “If you were a carpenter 200 years ago, you probably were much happier than today. Carpenters knew a lot about their craft and work included an artistic element too. With automation, we can get back to that era. The boring, repetitive tasks can be done by robots, giving us more freedom and space for the creative bits. Customers will also want more individualised products, so workers will have to think how to build them.” Robotics could also reduce the need for workers to commute, thinks Dr Schwartz. “It is possible to control robots remotely, so workers could be wearing augmented reality glasses and managing robots from their living room. They wouldn’t have to drive to work and could even work in a factory on a different continent,” he says.

In the short term, automation might make things easier for workers with the right qualifications. “Manufacturing requires well-trained workers, but it is not easy to find them. Just 20% of graduates today have a STEM degree, and by 2020 there will be an extra 900,000 open vacancies in the EU’s ICT sector. So manufacturers will have to automate not just to increase competitiveness, but also to attract the right talent, because these graduates will expect to have more interesting, state-of-the-art jobs,” says Rockwell’s Thomas Donato.

The picture might be different in industries where low-skilled work is the norm, such as retail, hospitality or the restaurant industry. Multinationals in these areas are already experimenting with AI solutions to replace workers. McDonald’s, a fast food chain, launched in January its first Big Mac ATM: a machine that dishes out burgers rather than bank notes. Andrew Puzder, CEO of CKE Restaurants and Donald Trump’s original choice for the position of Labour Secretary, said in an interview with Business Insider, that robots are “always polite, they always upsell, they never take a vacation, they never show up late, there’s never a slip-and-fall, or an age, sex, or race discrimination case.” Advancements in speech recognition technology may also wipe out jobs in areas involving verbal communication, such as customer service.

What happens next is a matter of political choice, believes Dr Schwartz: “Society has to think about what we are trying to accomplish through automation. Work is an important aspect of everyone’s life. Would full automation of production be a good thing? If most people are not employed and do not have any money to buy stuff, who are we producing for? This is not just an issue for IT and business people to think about. Politicians will have to think about it too.”

RECENT ARTICLES

-

AI now trusted to plan holidays more than work, shopping or health advice, survey finds

AI now trusted to plan holidays more than work, shopping or health advice, survey finds -

Could AI finally mean fewer potholes? Swedish firm expands road-scanning technology across three continents

Could AI finally mean fewer potholes? Swedish firm expands road-scanning technology across three continents -

Government consults on social media ban for under-16s and potential overnight curfews

Government consults on social media ban for under-16s and potential overnight curfews -

Twitter co-founder Jack Dorsey cuts nearly half of Block staff, says AI is changing how the company operates

Twitter co-founder Jack Dorsey cuts nearly half of Block staff, says AI is changing how the company operates -

AI-driven phishing surges 204% as firms face a malicious email every 19 seconds

AI-driven phishing surges 204% as firms face a malicious email every 19 seconds -

Deepfake celebrity ads drive new wave of investment scams

Deepfake celebrity ads drive new wave of investment scams -

Europe eyes Australia-style social media crackdown for children

Europe eyes Australia-style social media crackdown for children -

Europe opens NanoIC pilot line to design the computer chips of the 2030s

Europe opens NanoIC pilot line to design the computer chips of the 2030s -

Building the materials of tomorrow one atom at a time: fiction or reality?

Building the materials of tomorrow one atom at a time: fiction or reality? -

Universe ‘should be thicker than this’, say scientists after biggest sky survey ever

Universe ‘should be thicker than this’, say scientists after biggest sky survey ever -

Lasers finally unlock mystery of Charles Darwin’s specimen jars

Lasers finally unlock mystery of Charles Darwin’s specimen jars -

Women, science and the price of integrity

Women, science and the price of integrity -

Meet the AI-powered robot that can sort, load and run your laundry on its own

Meet the AI-powered robot that can sort, load and run your laundry on its own -

UK organisations still falling short on GDPR compliance, benchmark report finds

UK organisations still falling short on GDPR compliance, benchmark report finds -

A practical playbook for securing mission-critical information

A practical playbook for securing mission-critical information -

Cracking open the black box: why AI-powered cybersecurity still needs human eyes

Cracking open the black box: why AI-powered cybersecurity still needs human eyes -

Tech addiction: the hidden cybersecurity threat

Tech addiction: the hidden cybersecurity threat -

Parliament invites cyber experts to give evidence on new UK cyber security bill

Parliament invites cyber experts to give evidence on new UK cyber security bill -

ISF warns geopolitics will be the defining cybersecurity risk of 2026

ISF warns geopolitics will be the defining cybersecurity risk of 2026 -

AI boom triggers new wave of data-centre investment across Europe

AI boom triggers new wave of data-centre investment across Europe -

Make boards legally liable for cyber attacks, security chief warns

Make boards legally liable for cyber attacks, security chief warns -

AI innovation linked to a shrinking share of income for European workers

AI innovation linked to a shrinking share of income for European workers -

Europe emphasises AI governance as North America moves faster towards autonomy, Digitate research shows

Europe emphasises AI governance as North America moves faster towards autonomy, Digitate research shows -

Surgeons just changed medicine forever using hotel internet connection

Surgeons just changed medicine forever using hotel internet connection -

Curium’s expansion into transformative therapy offers fresh hope against cancer

Curium’s expansion into transformative therapy offers fresh hope against cancer