In Africa, hepatitis B is a silent killer. And a $1 test could stop it

John E. Kaye

- Published

- Science, Technology

Hepatitis B kills more than 270,000 people in sub-Saharan Africa each year, yet diagnosis, treatment, and political will remain dangerously low. Most victims are never even tested—despite early detection costing less than a cup of coffee. The time to act is now—before more lives are lost to this preventable and manageable disease, warns Professor Geoffrey Dusheiko

Hepatitis B is a well-known virus, but its full impact is often underestimated, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa where the burden is greatest and access to care is most limited. While global health initiatives have made strides against diseases like HIV, malaria and tuberculosis, hep-B has quietly overtaken them as a major cause of illness and death in the region. It is a leading driver of liver disease and cancer, killing more than 270,000 people annually in the World Health Organization’s African region alone.

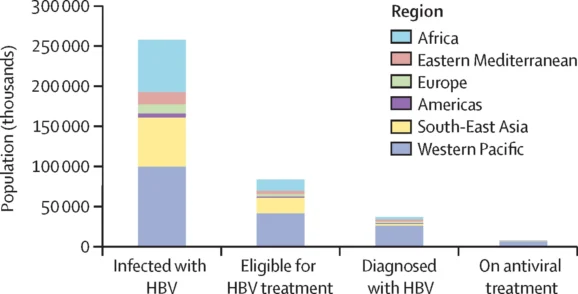

Worldwide, approximately 254 million people are living with chronic hep-B. Of those, around 64 million are in sub-Saharan Africa—one of the most heavily affected regions globally. The average prevalence is 6.5%, but awareness remains strikingly low. Only 2% of infected individuals know their status, and in this region an even smaller number—just 0.2%—are receiving treatment.

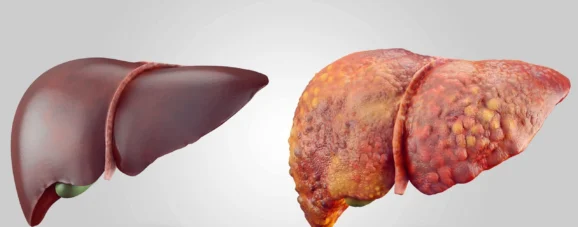

Infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV), primarily attacks the liver. It is transmitted through blood or bodily fluids, with the most common routes including childbirth, unprotected sex, and shared needles. While some people recover fully after an acute infection, others develop a chronic form of the disease that persists for life. This chronic infection may quietly damage the liver for decades, eventually leading to cirrhosis, liver failure or hepatocellular carcinoma, a highly aggressive form of liver cancer.

The course of the disease is often silent until the liver has sustained serious, irreversible damage. By the time symptoms or signs appear patients may already be in the late stages of illness. In many parts of Africa, where access to healthcare services is limited, this often results in extremely poor outcomes. Liver cancer caused by hep-B is now the third most common cause of cancer death among men in the region. The median survival after diagnosis is just three months.

The tragedy is that hep-B is both preventable and treatable. A safe and effective vaccine has been available since the 1980s, and it offers lifelong protection. The World Health Organization recommends administering the vaccine within 24 hours of birth to prevent mother-to-child transmission—one of the most common forms of infection in sub-Saharan Africa. However, only around 18% of infants in the region currently receive this critical birth dose. Weak health systems, gaps in maternal care, and low vaccine coverage continue to drive new cases.

Even after infection, the virus can be managed with low-cost antiviral medications. Tenofovir and entecavir—both available in generic form—are proven to reduce liver inflammation, reverse scarring, and cut the risk of liver cancer by more than 70%. A single tablet taken once daily costs less than $32 per year. These treatments don’t eliminate the virus entirely, but they can halt its progression and dramatically improve quality of life. However, awareness and diagnosis remains a major obstacle. In many areas, testing is either unavailable or unaffordable, and public understanding of the disease is limited. A simple point-of-care test—a USD$1 finger-prick blood test—can confirm infection on the spot, but it is rarely used at scale.

There are also social and structural barriers to overcome. In many communities, hep-B is still associated with shame and stigma. Misconceptions are common. People are unaware of how the virus is spread, or confuse it with HIV, deterring them from seeking care. Health literacy levels are often low, and many healthcare workers lack up-to-date training on diagnosis and treatment.

While global attention and funding have transformed the outlook for HIV in recent decades, hep-B has received far less focus from major international donors. This imbalance has contributed to the perception that it is less problematic, especially since a vaccine exists. But low coverage means that vaccination alone cannot solve the problem, especially with millions of people already living with chronic infection but not linked to treatment.

To change course, several things must happen simultaneously. Governments across the region must prioritise hep-B in their national health strategies and allocate resources to screening and treatment programmes. These services should be offered at the community level, using mobile clinics and digital platforms to extend reach. Integration with HIV programmes—many of which already have well-established infrastructure—offers a practical route to improve hep-B care.

Professional and research networks are beginning to make a difference. Organisations like the Gastroenterology and Hepatology Association of sub-Saharan Africa (GHASSA), the Society of Liver Disease in Africa (SOLDA), the nascent African Hepatitis B Advocacy Coalition and the HEPSANET research consortium are working to expand clinical capacity, adapt international guidelines to local contexts, and share region-specific data. Initiatives like Project ECHO are also helping to train healthcare workers in hepatitis management through virtual learning, even in remote areas.

There is also hope on the research front. New antiviral therapies, with the potential to cure hep-B, are now in advanced stage clinical trials. While these developments are promising, they remain several years away from widespread availability. In the meantime, early diagnosis and access to existing antiviral therapy remain the most powerful tools in reducing illness and death.

The economic case for action is strong. Treating end-stage liver disease or advanced cancer is far more expensive than preventing it. By investing in testing, education, vaccination, and low-cost treatment now, governments and international partners can prevent more costly interventions down the line.

With the right commitment, sub-Saharan Africa can make real progress toward hep-B elimination targets. The tools are available. But what is needed now is urgency, investment, and a shift in public health priorities. Hep-B has long been overlooked, but its impact is undeniable. The question is no longer whether we can do something about it—but whether we will.

Fact-File: Hepatitis B

What is it?

A virus that infects the liver. It can cause long-term illness, liver scarring (cirrhosis), and cancer.

How is it spread?

Through infected blood or bodily fluids—often during childbirth, unprotected sex, or shared needles.

Can it be prevented?

Yes. A safe, effective vaccine offers lifelong protection. The first dose at birth is crucial to prevent mother-to-child transmission, but antiviral therapy is needed for highly viremic mothers to prevent mother-to-child transmission.

Is there a cure?

No licenced cure yet, but a single, daily antiviral tablet can control the virus and reduce the risk of liver cancer by over 70%.

How common is it?

254 million people live with chronic hepatitis B globally—64 million in sub-Saharan Africa.

Why does it matter?

It often causes no symptoms until serious liver damage has occurred. In Africa, it’s a leading cause of liver cancer and death.

Professor Geoffrey Dusheiko, FCP(SA), FRCP, is Emeritus Professor of Medicine, University College London and Consultant Hepatologist at King’s College Hospital, London. He is a global authority on viral hepatitis, with research interests including hepatitis B and C, liver cancer, and antiviral therapies. He has served as an advisor to the World Health Organization and the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, and has authored more than 500 scientific publications.

Additional contributors:

Wendy Spearman (University of Cape Town)

Mark Sonderup (University of Cape Town)

Chris Kassianides (GHASSA)

RECENT ARTICLES

-

WPSL targets £16m-plus in global sponsorship drive with five-year SGI partnership

WPSL targets £16m-plus in global sponsorship drive with five-year SGI partnership -

Dubai office values reportedly double to AED 13.1bn amid supply shortfall

Dubai office values reportedly double to AED 13.1bn amid supply shortfall -

€60m Lisbon golf-resort scheme tests depth of Portugal’s upper-tier housing demand

€60m Lisbon golf-resort scheme tests depth of Portugal’s upper-tier housing demand -

2026 Winter Olympics close in Verona as Norway dominates medal table

2026 Winter Olympics close in Verona as Norway dominates medal table -

Europe’s leading defence powers launch joint drone and autonomous systems programme

Europe’s leading defence powers launch joint drone and autonomous systems programme -

Euro-zone business activity accelerates as manufacturing returns to expansion

Euro-zone business activity accelerates as manufacturing returns to expansion -

Deepfake celebrity ads drive new wave of investment scams

Deepfake celebrity ads drive new wave of investment scams -

WATCH: Red Bull pilot lands plane on moving freight train in aviation first

WATCH: Red Bull pilot lands plane on moving freight train in aviation first -

Europe eyes Australia-style social media crackdown for children

Europe eyes Australia-style social media crackdown for children -

These European hotels have just been named Five-Star in Forbes Travel Guide’s 2026 awards

These European hotels have just been named Five-Star in Forbes Travel Guide’s 2026 awards -

McDonald’s Valentine’s ‘McNugget Caviar’ giveaway sells out within minutes

McDonald’s Valentine’s ‘McNugget Caviar’ giveaway sells out within minutes -

Europe opens NanoIC pilot line to design the computer chips of the 2030s

Europe opens NanoIC pilot line to design the computer chips of the 2030s -

Zanzibar’s tourism boom ‘exposes new investment opportunities beyond hotels’

Zanzibar’s tourism boom ‘exposes new investment opportunities beyond hotels’ -

Gen Z set to make up 34% of global workforce by 2034, new report says

Gen Z set to make up 34% of global workforce by 2034, new report says -

The ideas and discoveries reshaping our future: Science Matters Volume 3, out now

The ideas and discoveries reshaping our future: Science Matters Volume 3, out now -

Lasers finally unlock mystery of Charles Darwin’s specimen jars

Lasers finally unlock mystery of Charles Darwin’s specimen jars -

Strong ESG records help firms take R&D global, study finds

Strong ESG records help firms take R&D global, study finds -

European Commission issues new cancer prevention guidance as EU records 2.7m cases in a year

European Commission issues new cancer prevention guidance as EU records 2.7m cases in a year -

Artemis II set to carry astronauts around the Moon for first time in 50 years

Artemis II set to carry astronauts around the Moon for first time in 50 years -

Meet the AI-powered robot that can sort, load and run your laundry on its own

Meet the AI-powered robot that can sort, load and run your laundry on its own -

Wingsuit skydivers blast through world’s tallest hotel at 124mph in Dubai stunt

Wingsuit skydivers blast through world’s tallest hotel at 124mph in Dubai stunt -

Centrum Air to launch first European route with Tashkent–Frankfurt flights

Centrum Air to launch first European route with Tashkent–Frankfurt flights -

UK organisations still falling short on GDPR compliance, benchmark report finds

UK organisations still falling short on GDPR compliance, benchmark report finds -

Stanley Johnson appears on Ugandan national television during visit highlighting wildlife and conservation ties

Stanley Johnson appears on Ugandan national television during visit highlighting wildlife and conservation ties -

Anniversary marks first civilian voyage to Antarctica 60 years ago

Anniversary marks first civilian voyage to Antarctica 60 years ago