Have we the energy for cryptocurrencies?

John E. Kaye

- Published

- Banking & Finance, Executive Education, Home, Technology

A knock-on effect of the recent crisis in Kazakhstan shows that mining may be the achilles heel of the cryptocurrency industry, says Nathalie Janson of NEOMA Business School

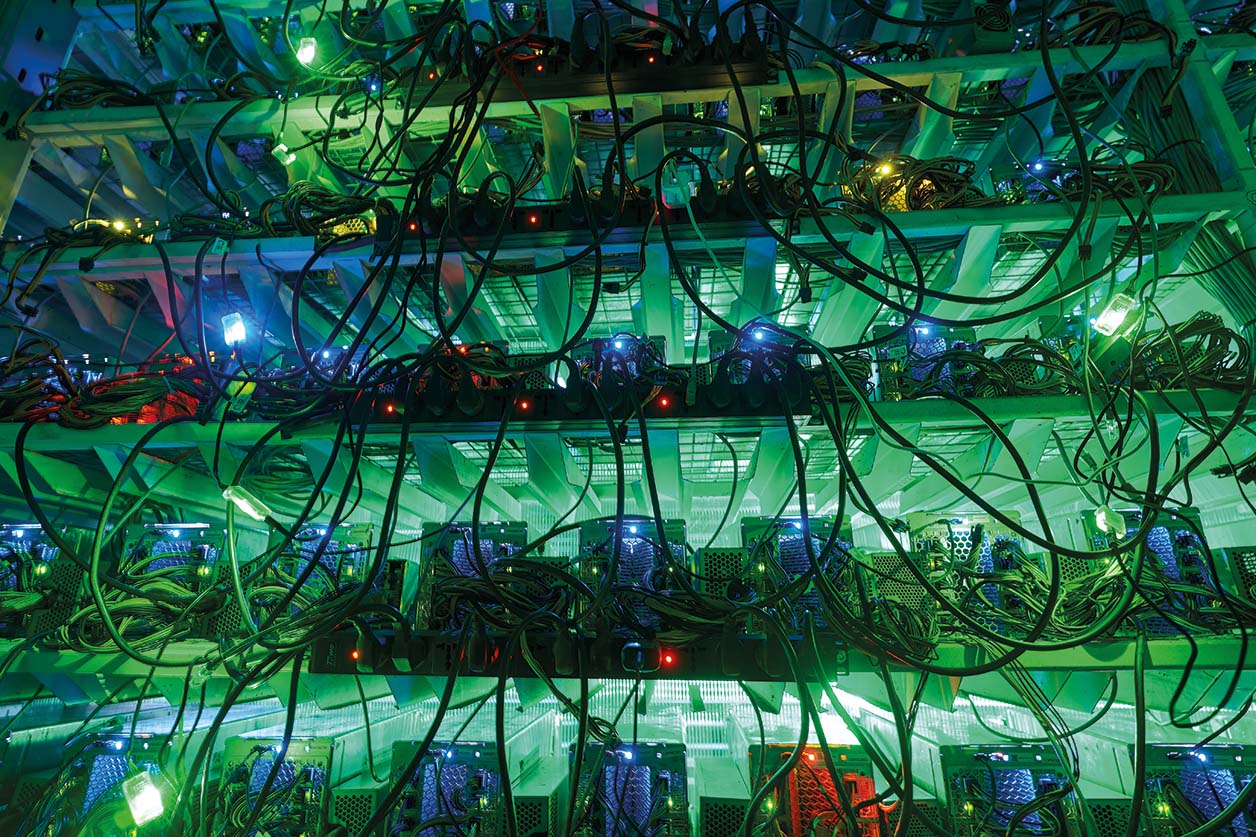

On January 5th 2022 – in the face of violent protests following a sharp increase in energy prices – the Kazak authorities disconnected large parts of the economy from the internet. One unforeseen consequence was that this led to a significant decrease in the price of bitcoin due to a sudden inability of miners to validate transactions and participate to the network. The price of bitcoin dropped from $48,000 on January 2nd to $41,000 on January 9th 2022. It became apparent that Kazakhstan had become a popular place for cryptocurrency mining, representing around 18% of the market share. Indeed, after China first banned the mining of cryptocurrencies in May 2021, followed by a total ban in November 2021, miners moved their supercomputers across the border to the central Asian country. Until May 2021, 75.5% of bitcoin mining was happening in China – but this has changed very quickly.

Unsurprisingly, the immediate consequence of China’s decision was a sharp decrease in the price of bitcoin. According to Coindesk, prices fell to $34,707 on May 24th and then $29,790 on July 21st 2021 following a record high in mid-April 2021 of $63,500. On that occasion, the cryptocurrencies market discovered how vital mining activity was despite the sense of security embedded in the design of bitcoin. Confirming transactions requires called miners to solve mathematical problems. The more miners, the more complex the mathematic problem.

The other interesting lesson of China’s mining ban is that the mining industry adapts relatively quickly. The supercomputers have been relocated to countries offering cheap electricity and easy access, such as the US, Kazakhstan, Russia – and also Sweden and Norway due to the availability of green energy. The “hashrate” (how much computing power is being used by a network to process transactions) went back to 90% of its average level as quickly as August 2021, just three months after the Chinese ban.

This relocation of cryptocurrency mining to Kazakhstan’s significantly impacted the country’s energy usage: a surge in consumption was first noticed in October last year. Up until this point, electricity demand had been growing by 1 to 2% a year and suddenly it surged by 8%, even causing black-outs in some areas. According to data collected by the Financial Times, “at least 87,849 power-intensive mining machines were brought to Kazakhstan” and not all of them legally. According the energy ministry 1200MW of electricity is siphoned by illegal miners, so called “grey miners”, twice as much as the registered “white miners”. Obviously, this unexpected increase in demand put huge pressure on the Kazakhstan power grid.

As of 2022, officially registered miners in Kazakhstan have to pay a $0.0023 tax per kWh in order to mitigate the pressure on energy infrastructure, and the country has negotiated to buy more electricity from Russia to match the higher demand.

With 18.2% of the market share, Kazakhstan is now the world’s second most prolific country for mining bitcoin. Any trouble here will have significant consequences on the price of bitcoin as investors understand that mining is, after all, an activity exposed to political risk. Unfortunately, this is only the beginning of the troubles. A growing opposition is developing in Northern European countries, including Sweden and Norway against mining activity. At the end of the UN Climate Change Conference in Paris Conference last November, the director generals at the Swedish Financial Supervisory Authority and the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency called for an EU ban on proof of work (PoW) mining as it threatens to negate transition efforts made by the region towards cleaner energy. In other words, they don’t want to see the production of green energy being consumed by an activity (the mining of cryptocurrencies) with questionable social benefits. Concerns regarding the energy footprint of cryptocurrencies is not new, indeed many studies have illustrated the high electricity consumption of mining activity.

What is proof of work?

Proof of work (PoW) is a form of cryptographic proof in which one party (the prover) proves to others (the verifiers) that a certain amount of a specific computational effort has been expended. Verifiers can subsequently confirm this expenditure with minimal effort on their part. Source, Wikipedia

Green efforts

Yet, over recent years, miners have significant efforts to make the electricity they use greener. This shift in policy started when they were still located in China. Today, opponents of cryptocurrencies still question the legitimacy of the use of green energy by the cryptocurrency industry on the grounds that it doesn’t add any positive value to the economy (since bitcoin are essentially held in portfolios for the sake of financial speculation). It goes against the argument once put forward by Jack Dorsey together with Elon Musk according to which cryptocurrencies represent an opportunity to drive the production of green energy. It is said that bitcoin mining can increase efficiency in renewable energy production by building an ecosystem where the likes of solar and wind power, batteries and bitcoin mining co-exist to form a green grid that runs almost exclusively on renewable energy. This would mitigate the issue that renewable sources often produce excessive supply when demand is low and struggle to meet needs of consumers and industry when demand is high.

According to Cambridge University, on average 39% of proof of work mining is powered by renewable energy, primarily hydroelectric energy. This share is higher than the 25% global average of share of renewables in electricity generation in 2019. “The Bitcoin Mining Network” report from CoinShares Research estimates the share of renewables used in bitcoin proof of work mining is as high as 74%.

Given that climate change is currently top of the political agenda of many developed countries, the big challenge for the cryptocurrency industry is without any doubt to win the battle over its energy consumption relative to its social benefit. Therefore, it will become less and less welcome.

After all, it is not the ban of its use that threatened its future, but the ban of its mining. If proof of work becomes outlawed on the grounds that it consumes too much green energy consumption, the DNA of bitcoin is clearly threatened. Bitcoin principles argue that proof of work is what cements its intrinsic value, since it verifies and validates the computational outcomes. Any alternative is less secure and not worth developing. Which is why much is expected of the Lightning Network: first used in 2017 this second layer of technology significantly decreases the energy consumption since the validation of transactions happens only on the balance of transactions and not for each single transaction. It also increases its efficiency in terms of number of transactions per second. It does this without compromising proof of work.

To conclude on a positive note, the cryptocurrency industry has demonstrated its agility over the past 13 years and its resilience through crises. If energy consumption for mining threatens its survival, developers must and will find ways to adapt. Maybe through the use of second layer protocols or maybe through less energy-intensive mining machines (or maybe both). One thing is certain, it will be fascinating to see how the situation pans out, both in terms of technology and policymaking worldwide.

About the author

Nathalie Janson is an Associate Professor at NEOMA Business School specialising in monetary policy, banking regulation and cryptocurrencies.

RECENT ARTICLES

-

Europe opens NanoIC pilot line to design the computer chips of the 2030s

Europe opens NanoIC pilot line to design the computer chips of the 2030s -

Building the materials of tomorrow one atom at a time: fiction or reality?

Building the materials of tomorrow one atom at a time: fiction or reality? -

Universe ‘should be thicker than this’, say scientists after biggest sky survey ever

Universe ‘should be thicker than this’, say scientists after biggest sky survey ever -

Lasers finally unlock mystery of Charles Darwin’s specimen jars

Lasers finally unlock mystery of Charles Darwin’s specimen jars -

Women, science and the price of integrity

Women, science and the price of integrity -

Meet the AI-powered robot that can sort, load and run your laundry on its own

Meet the AI-powered robot that can sort, load and run your laundry on its own -

UK organisations still falling short on GDPR compliance, benchmark report finds

UK organisations still falling short on GDPR compliance, benchmark report finds -

A practical playbook for securing mission-critical information

A practical playbook for securing mission-critical information -

Cracking open the black box: why AI-powered cybersecurity still needs human eyes

Cracking open the black box: why AI-powered cybersecurity still needs human eyes -

Tech addiction: the hidden cybersecurity threat

Tech addiction: the hidden cybersecurity threat -

Parliament invites cyber experts to give evidence on new UK cyber security bill

Parliament invites cyber experts to give evidence on new UK cyber security bill -

ISF warns geopolitics will be the defining cybersecurity risk of 2026

ISF warns geopolitics will be the defining cybersecurity risk of 2026 -

AI boom triggers new wave of data-centre investment across Europe

AI boom triggers new wave of data-centre investment across Europe -

Make boards legally liable for cyber attacks, security chief warns

Make boards legally liable for cyber attacks, security chief warns -

AI innovation linked to a shrinking share of income for European workers

AI innovation linked to a shrinking share of income for European workers -

Europe emphasises AI governance as North America moves faster towards autonomy, Digitate research shows

Europe emphasises AI governance as North America moves faster towards autonomy, Digitate research shows -

Surgeons just changed medicine forever using hotel internet connection

Surgeons just changed medicine forever using hotel internet connection -

Curium’s expansion into transformative therapy offers fresh hope against cancer

Curium’s expansion into transformative therapy offers fresh hope against cancer -

What to consider before going all in on AI-driven email security

What to consider before going all in on AI-driven email security -

GrayMatter Robotics opens 100,000-sq-ft AI robotics innovation centre in California

GrayMatter Robotics opens 100,000-sq-ft AI robotics innovation centre in California -

The silent deal-killer: why cyber due diligence is non-negotiable in M&As

The silent deal-killer: why cyber due diligence is non-negotiable in M&As -

South African students develop tech concept to tackle hunger using AI and blockchain

South African students develop tech concept to tackle hunger using AI and blockchain -

Automation breakthrough reduces ambulance delays and saves NHS £800,000 a year

Automation breakthrough reduces ambulance delays and saves NHS £800,000 a year -

ISF warns of a ‘corporate model’ of cybercrime as criminals outpace business defences

ISF warns of a ‘corporate model’ of cybercrime as criminals outpace business defences -

New AI breakthrough promises to end ‘drift’ that costs the world trillions

New AI breakthrough promises to end ‘drift’ that costs the world trillions