Could kibble be responsible for the deaths of one-in-25 pets?

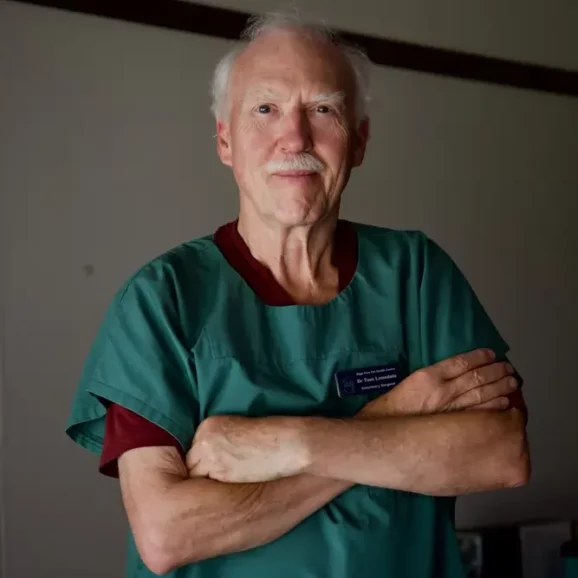

Dr Tom Lonsdale

- Published

- Opinion & Analysis

Thirty years ago, Dr Tom Lonsdale discovered a probable link between diet and terminal illness in the animal kingdom that he believes could have prevented the deaths of one-in-25 domesticated dogs and cats worldwide. His research was ignored

As of 2024, there were 26 million pet cats and dogs in Britain.

At the time of writing, up to one million of those animals will have died prematurely as an indirect result of their owners’ love and affection.

As a vet and scientist, it is my professional view that most, if not all, of those creatures could have been saved.

I have been researching the link between diet and terminal disease in the animal kingdom since the early ’90s and can say, with reasonable certainty, that dry pet food contributes to the deaths of one-in-25 cats and dogs worldwide at the minimum.

At the rate the global pet food market is growing, that number is likely to rise – to perhaps one-in-20 – within a decade.

By my reckoning, the overwhelming majority of those deaths are entirely preventable.

The terrible impact of kibble on animal health may at first seem hard to swallow. I agree it sounds unbelievable. Yet we need only look at nature itself for an explanation.

In the wild, carnivores – the wolves and wild cats from which our domesticated pets derive – eat a diet of predominantly raw meaty bones. The action of gnawing and crunching bones keeps their teeth clean and their gums in optimum condition.

Wild animals that cannot hunt or which are too low down in the pack’s pecking order to get the scraps, soon develop tooth decay and gum disease. Illness inevitably spreads to other organs and, in most cases, leads to premature death.

It’s a harsh reminder of natural selection in action: weaker animals must make way for stronger, fitter, specimens.

Most pets suffer serious gum disease by the time they are three years old. Despite their domestication, pets are still subject to the same laws of nature, and those which are not fed a wild-type diet of raw meaty bones will almost certainly succumb to the same fate.

Gum disease in the animal kingdom is very much an evolutionary instrument of death, and forms the central tenet of the Cybernetic Hypothesis, first presented in 1992.

Yet more than 30 years later, we are still giving our four-legged friends processed foods that lack the toughness and texture that’s needed to clean teeth and massage gums.

Ripping and tearing at the sofa or chair leg doesn’t confer the same benefits.

Ironically, owners are buying kibble because manufacturers tell them it’s not only good for their pets but essential. Many spend a fortune in the process.

Veterinary surgeons know the dangers, too, but ignore them in the pursuit of profit: sales of ‘pet toothbrushes’ (pointless) and processed dog and cat treats (harmful), and the income generated from regular dental cleanings under anaesthetic (entirely preventable), shore-up revenue in most vet practices.

It’s impossible to say with precise scientific accuracy how many cats and dogs die from eating kibble. But of the thousands of animals that I treated for periodontal disease in the course of my career, the majority that did not yet require surgery made a full recovery thanks to a prescription of raw, meaty bones. “It’s a miracle!”, owners would tell me, and I would agree. Nature is, indeed, miraculous.

Now is the time for manufacturers to make it clear on packaging that processed food is not and never will be a healthy replacement of raw, meaty bones.

Dr. Tom Lonsdale BVetMed MRCVS is a distinguished veterinary clinician and author with over 50 years of experience. Known internationally as a pioneer and authority on the nutritional and medicinal features of a natural diet for pets. Tom is a vocal advocate against what he perceives as collusion between the veterinary establishment and the pet food industry. He has earned the moniker, ‘The Whistleblower Vet’, for debunking misinformation about pet health.

Image: Dr Tom Lonsdale

RECENT ARTICLES

-

Why Europe’s finance apps must start borrowing from each other’s playbooks

Why Europe’s finance apps must start borrowing from each other’s playbooks -

Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes

Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes -

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others -

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again -

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart?

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart? -

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing -

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage -

The limits of good intentions in public policy

The limits of good intentions in public policy -

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament?

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament? -

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth -

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours -

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality -

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now -

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day -

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy -

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it -

What if he falls?

What if he falls? -

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world -

Will Trump’s Davos speech still destroy NATO?

Will Trump’s Davos speech still destroy NATO? -

Philosophers cautioned against formalising human intuition. AI is trying to do exactly that

Philosophers cautioned against formalising human intuition. AI is trying to do exactly that -

Life’s lottery and the economics of poverty

Life’s lottery and the economics of poverty -

On a wing and a prayer: the reality of medical repatriation

On a wing and a prayer: the reality of medical repatriation -

Ai&E: the chatbot ‘GP’ has arrived — and it operates outside the law

Ai&E: the chatbot ‘GP’ has arrived — and it operates outside the law -

Keir Starmer, Wes Streeting and the Government’s silence: disabled people are still waiting

Keir Starmer, Wes Streeting and the Government’s silence: disabled people are still waiting -

The fight for Greenland begins…again

The fight for Greenland begins…again