A postcard from the future

John E. Kaye

- Published

- Home, Technology

Alejandro Fernández-Cernuda Díaz, Director of Engagement in the Internet Integrity programme at Global Cyber Alliance explores the volatile digital landscape the world has found itself in following the pandemic

Last May 26, the Global Cyber Alliance brought together a group of international experts around one question—Has the pandemic marked a change of era in cybersecurity?

Or, to put it differently—is the future already here?

The new threat landscape

In order to address that question, we must start from an undeniable fact: the massive digitalisation that took place in 2020 was unprecedented. All of a sudden, we discovered that the digital future that had been announced to us for years was already here, within weeks and on a global scale.

Parallel to this —and taking advantage of the immediate global state of shock— cybercrime increased its activities exponentially.

Through a progression of high-impact actions, such as the SolarWinds incident, the attack against the European Medicines Agency or, in my country, Spain, the blocking of the public employment service, we have come to realise that digitalisation has brought vulnerabilities into our lives and that we are just part of a densely intricate chain.

Cybersecurity is no longer confined to the Technology section of the news. It now makes it to the cover stories, sometimes followed by deep geopolitical editorial analyses where concepts such as disinformation, digital warfare, or state-sponsored groups are part of the coverage.

On a more mundane level, the latest reports also show that petty cybercrime has been on the rise.

The growth of phishing —in spite of all our awareness efforts— is unstoppable. Likewise, ransomware is spreading through our supply chains, fuelled by the development of the Crime-as-a-Service industry and, paradoxical as it may seem, by the rise of cyber insurance.

The arrogance and brazenness common to many cybercriminals are now even marketing tools, as shown by DarkSide, the would-be Robin Hoods at the forefront of the Colonial Pipeline incident.

Cybercriminals take advantage of the impunity that still largely accompanies their activities. An impunity that relies upon the moderate effectiveness of cross-border collaboration, either among nations or within the multistakeholder model of internet governance.

The good news is that here, too, things seem to be changing.

Affairs of state

The campaign of attacks suffered by Australia at the onset of the COVID-19 crisis is characteristic of this new future in the present.

Quickly framed by the geostrategic conflict between China and Australia, the campaign received special media treatment. The public tone was raised, the accusations were virtually direct (‘95 per cent or more likely,’ Australian officials said), and China’s reaction was not precisely conciliatory.

Since 2020, either through cyber attacks or disinformation actions, similar episodes of verbal confrontation have occurred. However, even though those attacks are now more intense and disruptive and even though harsh communications are a component of current international relations, the novelty is not there.

The novelty lies in the need for today’s rulers to treat these crises as affairs of state, as opportunities to defend certain values against other antagonistic views. This need to fight for a specific model of internet sovereignty was clearly seen in President Biden’s recent European tour, culminating in a joint G7 statement and a face-to-face with Mr Putin.

Back to Australia, the other major development came in the Prime Minister’s statement in reaction to the incident.

After declaring ‘Cybersecurity is a shared responsibility of us all’ and pointing out the weakness of many Australian organisations in the face of complex cyber attacks, Mr Morrison went on to list a series of basic cyber hygiene tips, such as applying patches and updates or enabling multi-factor authentication. Truly unheard of in an institutional statement.

The relevance of such messages, in spite of their similarities to those of ‘Wash your hands, wear a mask, keep the distance’ of the pandemic, goes beyond political communication. They imply a need to involve the whole of society in the digital protection of the public. Cyber hygiene as an act of patriotism, as a new front in national defence.

The multistakeholder model rolls up its sleeves

The scale of cybercrime, the growing pressure of public opinion, and the Zeitgeist of COVID-19 have given momentum to collaborative cybersecurity projects such as the Charter of Trust, the CyberPeace Institute, the Cybersecurity Tech Accord, or MANRS. All of them have strengthened their activities and their impact during the pandemic.

The change of context has also made it possible to materialise initiatives such as the Ransomware Task Force, which has emerged as a voice of reference in some of the most publicised recent ransomware incidents; Domain Trust, which aims to address domain abuse, one of the pillars of cybercrime; or, on an exclusively state level but with consequences that affect several industries, the Cryptocurrency Enforcement Framework of the US Department of Justice.

The Big Five are also feeling the pressure and are becoming increasingly important and decisive in global cybersecurity.

Their involvement in some of the previous initiatives, the effectiveness with which they have survived the patching marathon of the past months, and the weight of their decisions on issues affecting global digitalisation, such as cloud security, the end of passwords, or email security, have made them one of the key drivers of change.

Their inescapable presence in our digital lives gives them great transformative power, but also a profound responsibility, a responsibility that, soon, with the intense legislative processes set in motion in both the US and the EU, could become hyper-regulated.

Cybersecurity and progress

Intensified regulation on cybersecurity is a consequence of its greater social relevance and the new threat landscape, but it also shows that the industry is expected to play a role in the recovery plans in the wake of COVID-19.

In this regard, Europe’s Digital Decade, the ambitious strategy recently published by the European Commission, deserves special mention.

Cybersecurity is shown there not only as a protection or defence mechanism but also as an empowerment tool for European citizens and businesses, by means of the development of awareness and cyberskills.

Once again, the novelty is not in the trend itself, but in the use that the EU is making of it to build its own, human-centered internet, where trust will support competitiveness and where normative power will be exercised through mechanisms such as the Horizon Europe funding scheme, the GDPR and NIS regulations, and future projects like DNS4EU.

Wrapping up

Back to the opening question, it seems sensible to state that we are surrounded by signs of change, even in those trends that, although already present in the past, have accelerated their consolidation.

It is probably too early to say whether the changes will be temporary or fundamental, whether we are already in the future, or whether we will end up returning to the immediate past, but one thing is clear—cybersecurity has never been so close to our societies.

It is time for them to take the reins. Whether the actual cyberfuture will be better or worse will depend exclusively on them.

Further information

Sign up to The European Newsletter

RECENT ARTICLES

-

Make boards legally liable for cyber attacks, security chief warns

Make boards legally liable for cyber attacks, security chief warns -

AI innovation linked to a shrinking share of income for European workers

AI innovation linked to a shrinking share of income for European workers -

Europe emphasises AI governance as North America moves faster towards autonomy, Digitate research shows

Europe emphasises AI governance as North America moves faster towards autonomy, Digitate research shows -

Surgeons just changed medicine forever using hotel internet connection

Surgeons just changed medicine forever using hotel internet connection -

Curium’s expansion into transformative therapy offers fresh hope against cancer

Curium’s expansion into transformative therapy offers fresh hope against cancer -

What to consider before going all in on AI-driven email security

What to consider before going all in on AI-driven email security -

GrayMatter Robotics opens 100,000-sq-ft AI robotics innovation centre in California

GrayMatter Robotics opens 100,000-sq-ft AI robotics innovation centre in California -

The silent deal-killer: why cyber due diligence is non-negotiable in M&As

The silent deal-killer: why cyber due diligence is non-negotiable in M&As -

South African students develop tech concept to tackle hunger using AI and blockchain

South African students develop tech concept to tackle hunger using AI and blockchain -

Automation breakthrough reduces ambulance delays and saves NHS £800,000 a year

Automation breakthrough reduces ambulance delays and saves NHS £800,000 a year -

ISF warns of a ‘corporate model’ of cybercrime as criminals outpace business defences

ISF warns of a ‘corporate model’ of cybercrime as criminals outpace business defences -

New AI breakthrough promises to end ‘drift’ that costs the world trillions

New AI breakthrough promises to end ‘drift’ that costs the world trillions -

Watch: driverless electric lorry makes history with world’s first border crossing

Watch: driverless electric lorry makes history with world’s first border crossing -

UK and U.S unveil landmark tech pact with £250bn investment surge

UK and U.S unveil landmark tech pact with £250bn investment surge -

International Cyber Expo to return to London with global focus on digital security

International Cyber Expo to return to London with global focus on digital security -

Cybersecurity talent crunch drives double-digit pay rises as UK firms count cost of breaches

Cybersecurity talent crunch drives double-digit pay rises as UK firms count cost of breaches -

Investors with €39bn AUM gather in Bologna to back Italy’s next tech leaders

Investors with €39bn AUM gather in Bologna to back Italy’s next tech leaders -

Axians and Nokia expand partnership to strengthen communications infrastructure across EMEA

Axians and Nokia expand partnership to strengthen communications infrastructure across EMEA -

Forterro buys Spain’s Inology to expand southern Europe footprint

Forterro buys Spain’s Inology to expand southern Europe footprint -

Singapore student start-up wins $1m Hult Prize for education platform

Singapore student start-up wins $1m Hult Prize for education platform -

UK businesses increase AI investment despite economic uncertainty, Barclays index finds

UK businesses increase AI investment despite economic uncertainty, Barclays index finds -

Speed-driven email security: effective tactics for phishing mitigation

Speed-driven email security: effective tactics for phishing mitigation -

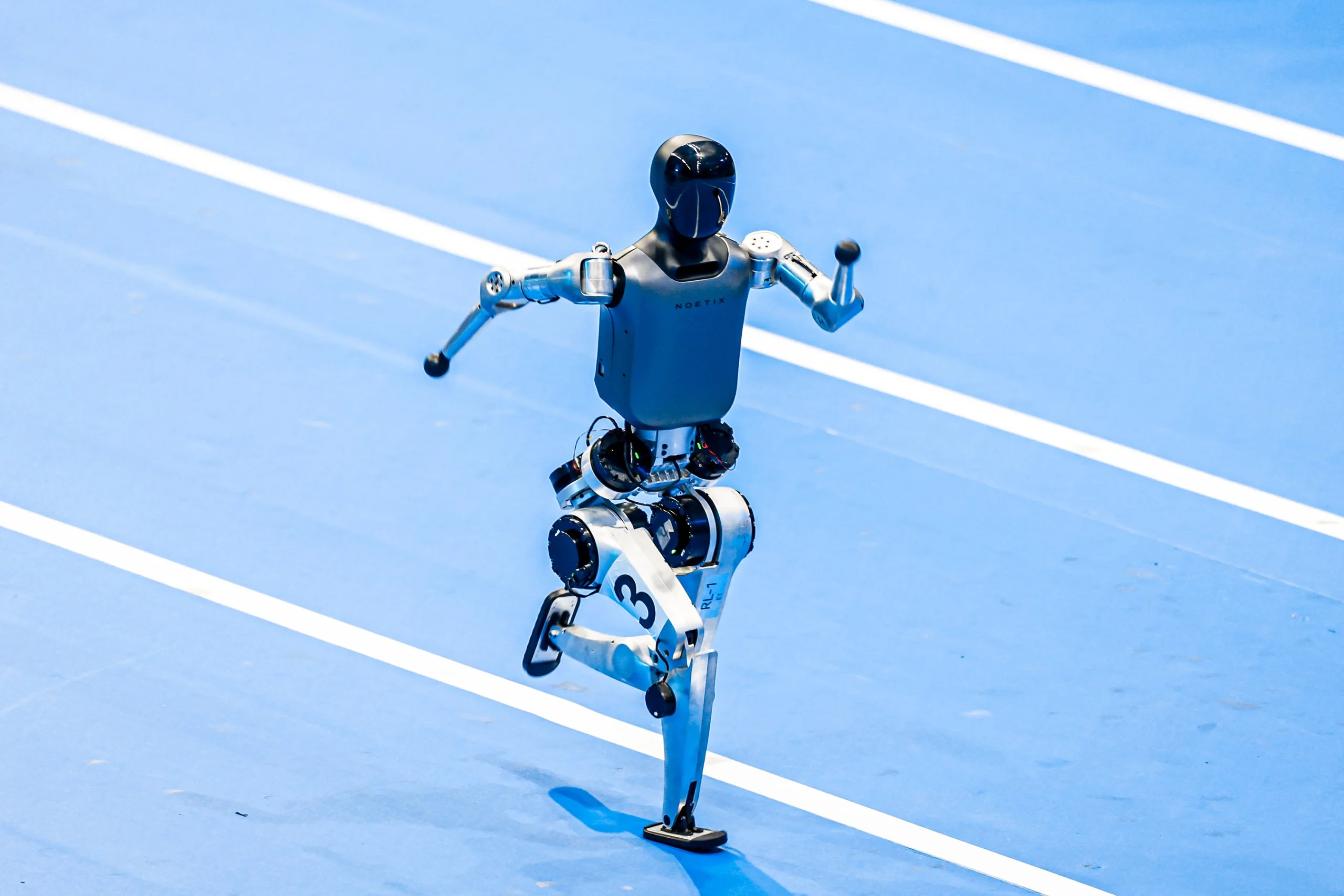

Short circuit: humanoids go for gold at first 'Olympics for robots'

Short circuit: humanoids go for gold at first 'Olympics for robots' -

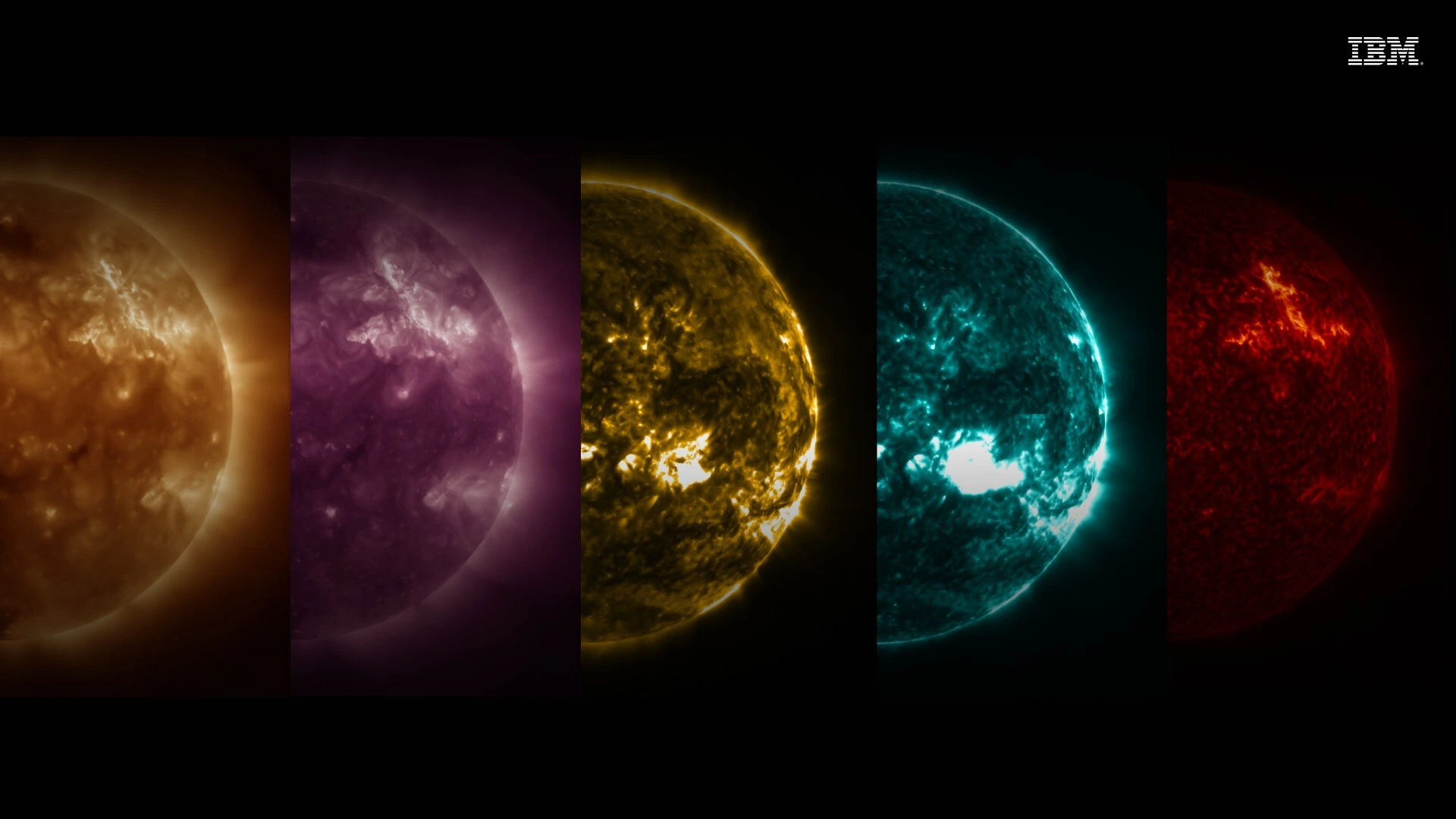

New IBM–NASA AI aims to forecast solar flares before they knock out satellites or endanger astronauts

New IBM–NASA AI aims to forecast solar flares before they knock out satellites or endanger astronauts -

AI is powering the most convincing scams you've ever seen

AI is powering the most convincing scams you've ever seen