We need to rethink workplace resilience

Sara-Louise Ackrill

- Published

- Opinion & Analysis

From executive retreats to corporate away days, we still expect leaders to socialise, perform and recharge in exactly the same way. But for neurodivergent professionals, and for many others, that expectation is not only unrealistic, it’s unsustainable, warns workplace inclusion specialist, Sara-Louise Ackrill

In the days leading up to a corporate away day or team-building event, I frequently hear concerns from neurodivergent senior leaders who are already trying to calculate the emotional and logistical toll. They are expected to attend back-to-back seminars, manage evening entertaining, maintain professional visibility throughout, and immediately return to work upon arrival home—often late, often drained, often without rest. For many, these events are set in unfamiliar locations and climates that are physically or mentally challenging. While this may be intended as a break from routine, for some it presents a significant source of stress.

These events, whether held domestically or overseas, are often framed as opportunities to “collaborate”, “re-energise”, and “invest in culture”. But in practice, they require careful planning and substantial emotional energy, particularly for those who are balancing ongoing responsibilities at home. Personal lives, including children, partners, caring duties and pets, do not pause to accommodate the extended demands of these corporate excursions. Frequently, those responsibilities are handed over to others, including professionals we may not know well, in order to meet the expectation of being present, focused, and socially engaged outside of typical working hours.

There are many roles in which this kind of additional effort is regarded as a standard part of professional life. For some, the opportunity to work from different locations and connect with colleagues in a more informal setting may feel valuable. For others, it represents a logistical challenge and a personal cost that is rarely acknowledged. The same event can serve as both privilege and pressure, depending entirely on individual circumstances and internal states.

This is where the discussion around neurodiversity becomes particularly relevant.

Approximately 22 per cent of the general population is considered neurodivergent, and within leadership roles and high-performing sectors such as law, consultancy, technology, and the creative industries, that figure is significantly higher. It is estimated that at least 35 per cent of professionals in these environments identify with traits or formal diagnoses that include autism (previously known as Asperger’s Syndrome), ADHD, dyslexia, sensory processing differences, and other neurodevelopmental profiles.

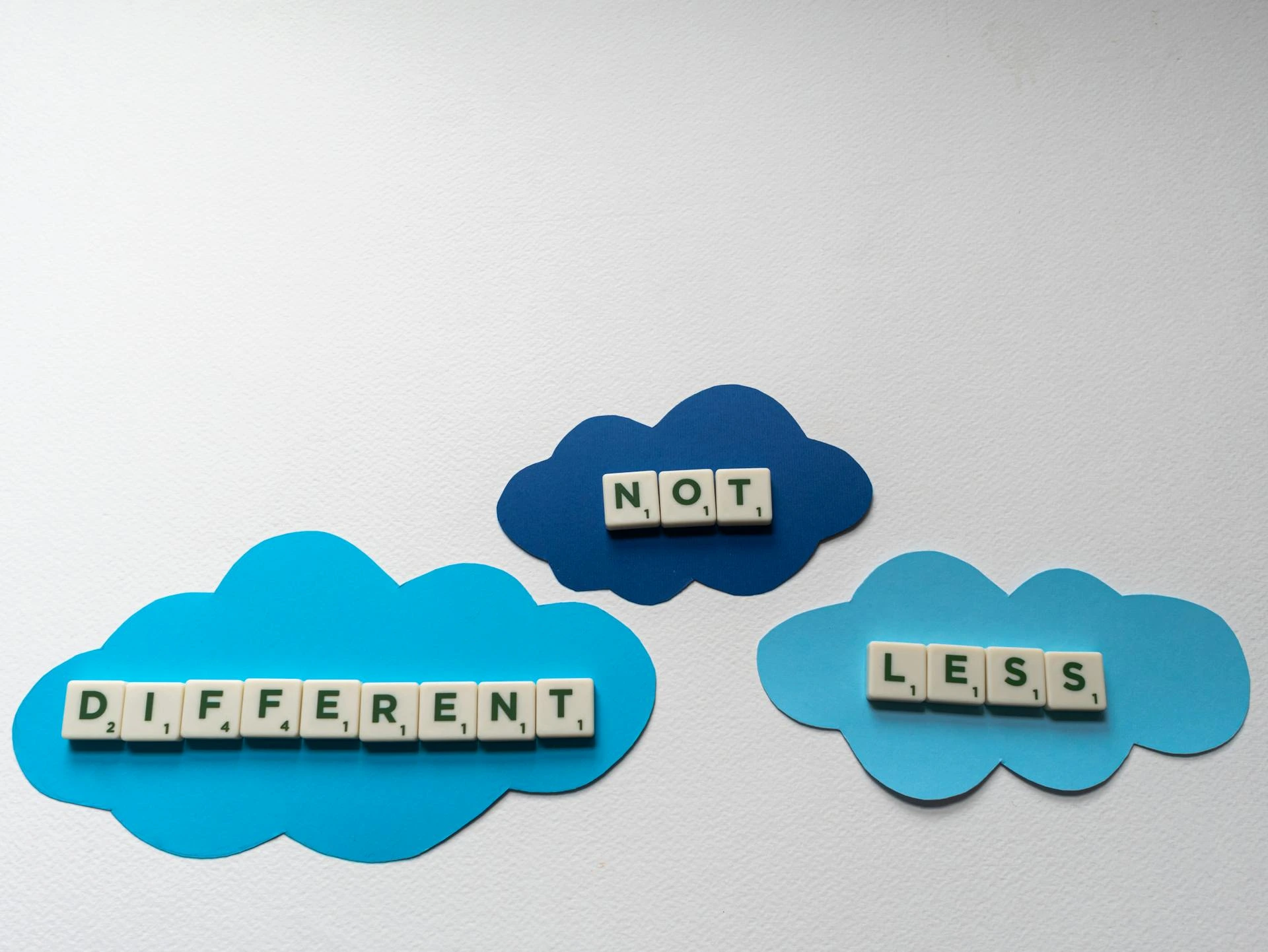

Individuals who are neurodivergent typically have no intellectual impairment although often people assume they go together (which is why neurodivergent professionals are so often an invisible population). In fact, many have exceptional cognitive and creative strengths. However, the way their brains process information, regulate emotion, manage executive function, and communicate socially can differ markedly from what is considered typical. That difference is not inherently disabling, but the expectations imposed by traditional professional environments often are.

There has been growing recognition that not everyone experiences the world in the same way, even when there are no visible signs of difference. However, awareness alone is not enough. The persistent expectation that all professionals should work in the same way, behave in the same way, and respond to pressure in the same way is outdated and exclusionary. It is entirely possible for people to perform well and achieve meaningful outcomes, but they will not all reach those outcomes by following identical routes.

If your organisation has already invested in neurodiversity awareness training or invited external speakers to begin these conversations, you are further ahead than many. That may be because colleagues requested it, because your sector now demands it, or simply because you recognise the importance of doing so. Whatever the motivation, it is a start and a valuable one. Of course, in a just world, this work would have begun far earlier. Neurodivergent and disabled people have always existed. We should not, in 2025, still be having to advocate for these basic recognitions. But we are, and in that context, taking a first step still matters.

One of the patterns I observe most consistently in my work is the unspoken insistence that everyone within an organisation, and particularly those in leadership positions, must demonstrate resilience in the same way. That expectation is rarely made explicit, but it is deeply embedded. It can be heard in remarks like, “You’re in charge – this comes with the role,” or “We rely on you to set the tone.” The implication is clear: strength means uniformity, and resilience means tolerating pressure without complaint.

There is a crucial difference between what a role requires and how that role is performed. Those two things are not the same, and it is important that we stop treating them as if they are. Leadership does not demand emotional suppression or the rejection of personal needs. Rather, it requires clarity, integrity, and sustainability. The ability to recover and remain consistent over time is far more valuable than the ability to perform under duress for short periods while suppressing what one actually requires.

Many professionals, and in particular those who are neurodivergent, require space, time alone, opportunities to process, or the chance to step back from prolonged interaction. While these might sound like mere indulgences, they are in fact essential strategies for maintaining focus, regulating emotional responses, and protecting one’s mental health. Expecting people to function indefinitely without access to these mechanisms is a sign of systemic denial and not, as we are led to believe, one of a strong organisational culture.

It is well understood among parents of neurodivergent children that what appears calm or cooperative in public may come at a private cost. A child who holds everything together during school hours may come home and unravel completely. Such responses are not “tantrums” but symptoms of overload. The so-called “fizzy bottle of pop” analogy is often used: the pressure builds gradually, then explodes when the lid is finally removed. That same dynamic plays out in adult life. It happens in hotel rooms, on return flights, in private homes, often witnessed only by loved ones. The context is corporate, but the consequence is deeply personal.

None of this diminishes a person’s competence, intelligence, or professionalism. Neurodivergence does not disappear with seniority. In fact, it remains a part of who someone is, no matter their job title or how polished their presentation may seem.

Not every neurodivergent leader will choose to disclose their identity, and they should never be expected to. However, all leaders have the opportunity to model inclusive practices. These can be simple, deliberate choices: making space in the schedule for personal downtime; offering structured activities that are optional rather than compulsory; signalling openly when one needs quiet or time alone; or giving colleagues the same permission to express their own needs.

Small changes often make a significant difference. The use of noise-cancelling headphones, the availability of fidget tools, quiet breakout areas, clear agendas, or advance materials all allow individuals to plan, regulate and participate more comfortably. Social activities that do not centre around alcohol, structured networking that does not rely entirely on spontaneous small talk, and a choice of formats for engagement also benefit a wide range of people, not only those who identify as neurodivergent.

Much of the leadership development work I do involves unpicking the institutional belief that resilience means silence and sameness. Resilience, in fact, means adaptability. It means recognising your own needs, and supporting others to do the same. Authenticity is, after all, an expression of confidence and maturity and leaders who model this appear more trustworthy.

If we continue to expect senior professionals to absorb all emotional cost quietly and indefinitely, we risk normalising burnout as a marker of commitment. This is neither healthy nor productive. Instead, we must redefine what good leadership looks like. It must include rest. It must include recovery. It must include room for difference.

The next time a senior figure is encouraged to ‘show resilience’ we would do well to consider what that really means. If it amounts to the erasure of their humanity, then it is time to stop calling it a strength. It is simply denial…and it is no longer working.

Sara-Louise Ackrill is a neurodivergent therapist, entrepreneur, and workplace consultant. Founding CEO of Wired Differently and co-founder of Start Differently, a non-profit, Sara-Louise supports neurodivergent individuals personally in employment and as entrepreneurs. Recognised as a ‘Top UK Neurodiversity Evangelist’ and one of Small Business Britain’s #IAlso100 2024 entrepreneurs, Sara specialises in workplace inclusion, neurodiversity awareness, and domestic abuse awareness in the workplace advocacy. She is currently developing wNDerful, an app for neurodivergent people, and strives to create inclusive spaces through psychoeducation and compassion.

Main image: Polina/Pexels

RECENT ARTICLES

-

The era of easy markets is ending — here are the risks investors can no longer ignore

The era of easy markets is ending — here are the risks investors can no longer ignore -

Is testosterone the new performance hack for executives?

Is testosterone the new performance hack for executives? -

Can we regulate reality? AI, sovereignty and the battle over what counts as real

Can we regulate reality? AI, sovereignty and the battle over what counts as real -

NATO gears up for conflict as transatlantic strains grow

NATO gears up for conflict as transatlantic strains grow -

Facial recognition is leaving the US border — and we should be concerned

Facial recognition is leaving the US border — and we should be concerned -

Wheelchair design is stuck in the past — and disabled people are paying the price

Wheelchair design is stuck in the past — and disabled people are paying the price -

Why Europe still needs America

Why Europe still needs America -

Why Europe’s finance apps must start borrowing from each other’s playbooks

Why Europe’s finance apps must start borrowing from each other’s playbooks -

Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes

Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes -

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others -

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again -

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart?

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart? -

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing -

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage -

The limits of good intentions in public policy

The limits of good intentions in public policy -

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament?

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament? -

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth -

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours -

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality -

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now -

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day -

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy -

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it -

What if he falls?

What if he falls? -

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world