A snowflake army: why UK conscription is a bad idea

John E. Kaye

- Published

- Opinion & Analysis

Amid growing concerns of global security, the idea of reinstating conscription in the UK has resurfaced as a potential solution to strengthen its dwindling military forces. But the idea of a snowflake-led British Army would damage our credibility as a military power—and give our enemies something to laugh about, warns former Tank Commander and author, Matthew Baldwin

At first glance, it seems like a practical way to strengthen the British armed forces, which have been stretched thin due to global commitments and the changing nature of modern warfare. But the reality is far more complex than simply filling ranks. The UK’s younger generation is far less prepared for the rigours of military life than any previous generation. This fundamental shift in mentality may render conscription unworkable, no matter how much it’s painted as a necessity.

The primary issue with conscription is motivation. The military needs a solid, convincing reason to get people to enlist—and to make sure they don’t try to avoid it. In the event of a national emergency, where the survival of the country is at stake, this could work. But for conscription to succeed in peacetime, or in response to threats like those faced by Ukraine, the idea of signing up must resonate personally with potential recruits.

During wartime, UK conscription initially targeted men aged 18 to 41, as seen during World War II. As the war dragged on, and the need for more soldiers grew, the age range was expanded to include men aged 18 to 51. Women aged 20 to 30 were also required to serve in non-combat roles. However, in peacetime, conscription typically focused on younger age groups, usually between 18 and 30, as seen with the National Service Act of 1948, which required men within this range to serve for around 18 months.

Today, conscription would likely focus on the same age range of 18 to 30, especially for roles like peacekeeping or other less demanding duties. The problem is that this generation is accustomed to comfort. With constant access to smartphones, social media, and instant gratification, many young people have not experienced any physical discomfort, let alone that which military service demands. This isn’t their fault—it’s the product of a society that values comfort over resilience. As a result, convincing young people to enlist, particularly for causes unrelated to national defence, would require a fundamental shift in their mindset.

Then there’s the practical side of things—recruitment logistics. Who would be conscripted? Would the government cast a wide net or target specific demographics, like the regimental systems of the First World War? The government might consider pulling National Insurance numbers at random, but this could lead to public uproar. Would parents accept the conscription of their children, or would we see drawn-out legal battles as families try to prevent their loved ones from being drafted? Forcing young people—many of whom are ill-prepared for the discipline of military life—into the armed forces could spark protests the likes of which we haven’t seen since Brexit.

Even if conscription were enacted and enough recruits were found, the logistical challenges would still be enormous. The British Army currently has around 76,300 full-time soldiers. Even with reserve forces included, the total barely reaches 108,000. This is just enough to maintain the army’s official status, yet the idea of suddenly doubling or tripling the number of soldiers in a short time is an almost impossible task. The government would have to find the funds to train, house, equip, and feed thousands of new recruits—an overwhelming challenge for a system already stretched thin.

In 2003, the UK sent 40,000 troops to Iraq. This operation, of which I was a part, nearly broke the military’s logistical capacity. So, to suddenly accommodate and supply an additional 100,000 to 200,000 soldiers would put an unbearable strain on an already fragile system. The notion of pulling office workers, coffee shop workers, and influencers off the streets and turning them into soldiers within months seems far-fetched, given the time and resources needed to support them.

Then there’s the issue of training. The Army’s current strength is built on a foundation of soldiers who have willingly and actively joined up. These are individuals who have committed to their roles and understand the physical and mental demands they’re likely to face. Many are aged between 18 and 30 and are some of the toughest, most resilient people on the planet. Conscripts, however, would be forced into service, many with no interest in military life and no desire to acquire the necessary skills.

Basic Army training is brutal. Recruits are pushed to their limits both mentally and physically. From day one, they face the intense demands of military life. The fitness requirements are far beyond what most young people are used to. Yes, more young people than ever go to the gym and keep fit. But fewer than ever engage in the kind of physical endurance needed in the Army. Unlike a gym environment, where you can stop whenever you want, Army training is relentless. Recruits must march for miles, carry heavy packs, and endure gruelling exercises in all kinds of weather, often on little sleep. This physical strain is combined with the mental challenges of learning to follow orders without question, work as a team, and quickly adapt to a disciplined, highly structured environment.

For many young people today, this would be a major shock. Millennials and Gen Z-ers, particularly those in urban areas, lack many of the resilience skills that would help them thrive in such a harsh environment. They’re more used to spending time on devices, enjoying the ease of modern life, and have rarely encountered the kind of tough, physical work that military service demands. Suddenly being stripped of their luxuries, with no access to smartphones or social media, would be a jarring experience.

Army recruits go through 12 weeks of basic training, followed by specialised training that can take another 6 to 12 weeks, depending on the role. By the time they are ready for deployment, they’re still at the bottom of a steep learning curve. Now, imagine trying to train a large group of conscripts who have no interest in being there. The soldiers tasked with training them would face a monumental challenge. They’d have to teach people who’d rather be anywhere else and who likely would be focused more on how to escape than on learning what they need to succeed. This is a challenge already faced by the Russian and Ukrainian armies, both of which have struggled with high rates of desertion and low morale among conscripts. Their efforts show just how difficult it is to turn unwilling recruits into effective soldiers, especially when motivation and commitment are lacking.

With only 76,300 full-time soldiers and many of them already stretched thin on operations or training, it would be nearly impossible to find enough experienced trainers for such a large influx of new recruits. Even if former soldiers or older veterans were called up to help, they’d still be working with unwilling conscripts, which would undermine any training programme. The lack of motivation and commitment among conscripts would likely cripple the effectiveness of training, no matter how well-designed it was.

Another major issue is desertion and conscientious objection. Given today’s climate, it’s highly likely that a large number of conscripts would try to avoid service. Some would simply refuse to enlist, challenging the conscription in court or turning to the media to voice their opposition. Social media would also play a major role in this. Those who try to desert or conscientiously object could quickly become social pariahs, using social media to gain support for their stance. The combination of legal

battles and widespread social media support would likely create a significant divide in society, intensifying public pressure and further straining the military’s ability to function effectively.

So, what would conscripts actually be trained to do? In the event of an overseas war, would they be sent to fight in dangerous, volatile environments? Or would they remain in the UK, tasked with domestic defence? If it’s the latter, then the necessity for conscription becomes even more questionable.

The idea of a half-trained, largely unmotivated force being sent into combat is frightening, especially considering the immense sacrifices required in modern warfare. The idea of conscripts, who are more familiar with TikTok than tactics, trying to form a credible military force would make us a target for ridicule. Any potential adversary would see a weakened, unprepared force, and that perception alone could embolden them.

This brings us back to the fundamental issue: motivation. If conscription is seen as a way to fight another country’s war, it’s likely to fail. No one wants to send their sons and daughters to fight a foreign conflict—especially when those soldiers have been conscripted and aren’t mentally or emotionally prepared for the realities of war. History shows that conscription can lead to massive public unrest, as seen during the Vietnam War in the United States. People don’t want to fight wars they don’t believe in, and they certainly don’t want to send unwilling individuals to do so.

However, if conscription were viewed as a means to defend the UK against an immediate threat—such as an invasion or direct attack—the situation might be different. In this case, the urgency and personal stakes would likely shift the mindset of conscripts. The “Dunkirk spirit” would kick in, and people might be more willing to endure the hardships of military life for the sake of their country and loved ones.

Even so, the challenges of training, equipping, and motivating a conscript army remain. The harsh, relentless world of military training would be a jarring shock to a generation that’s never had to push beyond its limits. It’s hard to imagine today’s young people willingly stepping into a world that strips away the luxuries they’ve come to depend on—especially when that world demands so much more than they’ve ever been asked to give. They’re like flowers grown in a greenhouse—protected, pampered, and sheltered from the storms. Asking them to suddenly endure the harsh conditions of military life would be like expecting them to survive in a blizzard. And the UK’s young snowflakes wouldn’t just struggle in the cold—they’d quickly melt away.

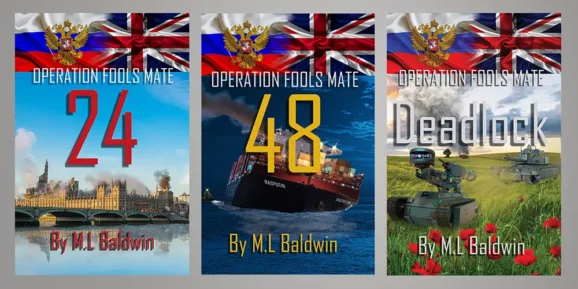

Matthew Baldwin is a decorated former Tank Commander who joined the Second Royal Tank Regiment in 1996. Over his 19-year career, he served on operations in Northern Ireland, Kosovo, Iraq, and Afghanistan, earning a Mention in Despatches (MiD) during his final tour in Afghanistan. After leaving the military, he turned to writing and began his journey as an author. His acclaimed Operation Fools Mate series—24, 48, and Deadlock—is inspired by his extensive military experience. The books are available on Amazon, Waterstones, and other major retailers.

RECENT ARTICLES

-

The era of easy markets is ending — here are the risks investors can no longer ignore

The era of easy markets is ending — here are the risks investors can no longer ignore -

Is testosterone the new performance hack for executives?

Is testosterone the new performance hack for executives? -

Can we regulate reality? AI, sovereignty and the battle over what counts as real

Can we regulate reality? AI, sovereignty and the battle over what counts as real -

NATO gears up for conflict as transatlantic strains grow

NATO gears up for conflict as transatlantic strains grow -

Facial recognition is leaving the US border — and we should be concerned

Facial recognition is leaving the US border — and we should be concerned -

Wheelchair design is stuck in the past — and disabled people are paying the price

Wheelchair design is stuck in the past — and disabled people are paying the price -

Why Europe still needs America

Why Europe still needs America -

Why Europe’s finance apps must start borrowing from each other’s playbooks

Why Europe’s finance apps must start borrowing from each other’s playbooks -

Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes

Why universities must set clear rules for AI use before trust in academia erodes -

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others

The lucky leader: six lessons on why fortune favours some and fails others -

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again

Reckon AI has cracked thinking? Think again -

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart?

The new 10 year National Cancer Plan: fewer measures, more heart? -

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing

The Reese Witherspoon effect: how celebrity book clubs are rewriting the rules of publishing -

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage

The legality of tax planning in an age of moral outrage -

The limits of good intentions in public policy

The limits of good intentions in public policy -

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament?

Are favouritism and fear holding back Germany’s rearmament? -

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth

What bestseller lists really tell us — and why they shouldn’t be the only measure of a book’s worth -

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours

Why mere survival is no longer enough for children with brain tumours -

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality

What Germany’s Energiewende teaches Europe about power, risk and reality -

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now

What the Monroe Doctrine actually said — and why Trump is invoking it now -

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day

Love with responsibility: rethinking supply chains this Valentine’s Day -

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy

Why the India–EU trade deal matters far beyond diplomacy -

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it

Why the countryside is far safer than we think - and why apex predators belong in it -

What if he falls?

What if he falls? -

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world

Trump reminds Davos that talk still runs the world