Drive your own safari: why Kruger is Africa’s most accessible wildlife park

Professor Tim Coulson

- Published

- Lifestyle

With low malaria risk, wide-open roads and wildlife in abundance, now is the ideal time to visit South Africa’s Kruger National Park. Biologist and author Professor Tim Coulson, a near-annual visitor, reveals why this vast, self-drive reserve remains one of Africa’s most accessible — and rewarding — safari destinations

If you want to set your own pace while still seeing Africa at its wildest, there are few better places than South Africa’s Kruger National Park. Set across nearly 20,000 square kilometres of lowveld savannah, bush and riverine forest, Kruger is vast, varied and astonishingly well run. It’s a place where you can spend a morning with elephants, an afternoon identifying eagles, and an evening grilling steaks beneath the stars, all without ever leaving the park.

Unlike many of the continent’s most celebrated safari destinations, Kruger doesn’t require a guide or an organised tour. You can land, pick up a hire car, and within a few hours be parked beside a pride of lions.

That independence makes it unusually accessible and, for my wife Sonya and me, unusually addictive; we return most years, drawn back by the chance to explore on our own terms and the promise of wildlife we’ve yet to see. In July we returned and met up with nine of Sonya’s Australian family and friends who had flown in from Brisbane.

Sonya and I are biologists by profession. Between us, we’ve worked in tropical rainforests and coral reefs, radio-tracked elephants, surveyed turtles, and slept in hammocks or under canvas on almost every continent except Antarctica. These days, though, we favour comfort and continuity, and Kruger delivers both. It’s the only African national park we know where you can track wild dogs before breakfast and be on a golf course by midday — assuming you don’t mind losing the occasional ball to hippos.

Like many protected areas in Africa, Kruger’s past is not without complications. Its history is shaped by colonialism, forced removals and a long struggle over land and access. But none of that detracts from what makes it exceptional today: a vast, well-run wilderness where wild animals live much as they always have, and where visitors are given the rare freedom to navigate it for themselves.

What to see

Kruger is home to all of the Big Five — lion, leopard, buffalo, elephant and rhino — along with more than 500 species of birds and an extraordinary diversity of reptiles, antelope and smaller mammals. For the casual visitor, game drives reliably deliver elephants, giraffes, zebras and hippos. But with a few unhurried days behind the wheel — and with patience — you begin to see so much more besides: mongoose darting across dry roads, lilac-breasted rollers flashing between branches, and vultures jostling for position on carrion.

On our most recent trip, we saw lions feeding on a kill, had two excellent rhino sightings, and were politely (but firmly) blocked by a young bull elephant who claimed the road for twenty minutes. Even in the quiet stretches — and there are some — there’s always something to look for. Identifying hornbills or watching a herd of impala navigate a bend in the river is part of the daily rhythm.

For the serious birder, Kruger is superb. Raptors patrol the thermals; storks, egrets and herons crowd the riverbanks; and even casual observers soon learn to identify a lappet-faced vulture from a white-backed. We recorded over 150 species between us and took more than 10,000 photos, helped in no small part by a rented Canon 400mm lens, worth every euro.

How to explore

What sets Kruger apart is how easily it can be done independently. If you’re driving yourself, the most common route is to fly into Johannesburg, hire a car, and take the four- to five-hour drive east to one of the park’s southern gates such as Paul Kruger or Malelane. We chose a quicker route: flying from London to Johannesburg, then connecting via Airlink into Skukuza Airport, which lies inside the park itself. From there, the 11 of us picked up three large 4x4s (the extra height makes a big difference when trying to spot wildlife in long grass or bush, and it also means you’re not peering up at elephants or buffalo from below) and spent 10 days moving between rest camps.

Kruger’s self-drive model is unusual for Africa. More than 2,400 kilometres of roads — a mix of tar and gravel — give visitors the freedom to plan each day as they choose. Want to spend half an hour identifying vultures? Go ahead. Want to follow a dusty track down to a riverbank on a hunch? No one’s stopping you. The speed limits are 50km/h on tar and 40km/h on gravel, which feels generous until you realise how often you’ll be slowing down to scan the bush or wait for elephants to cross the road.

For those who prefer more structure, guided options are easy to arrange. Organised morning, sunset and night drives are available from most camps and are often led by expert trackers. Sunset and evening outings offer a chance to see nocturnal species like bush babies, galagos and genets, species that are all but impossible to find on your own during the day. But for us, the greatest pleasure was the quiet routine of self-drive days: watching, waiting, making our own decisions, and learning as we went.

Where to stay

SANParks, which manages the park, operates 13 main camps. We stayed in three: Skukuza (the largest), Olifants (with spectacular river views), and Mopani (quieter and less trafficked). Accommodation is simple but comfortable, with most camps offering a range of bungalows, shops, fuel and a reasonable restaurant.

Some evenings we cooked ourselves on the outdoor braai; other nights we ate out — where even a meal for 11, with drinks, came in under £250. The food is superb (think hearty, not haute cuisine), and vegetarian options are limited but improving.

For a more exclusive experience, private reserves bordering the eastern edge of the park offer luxury safari lodges and guided experiences. On a previous trip, we stayed at Antares Bush Camp, a self-catering lodge (though you can arrange your own private chef) with its own sunken waterhole hide. There, we saw nocturnal species rarely visible in the main park and went on highly personalised game drives with an exceptional guide.

Unexpected extras

Not everything in Kruger is about game viewing, or at least not directly. One afternoon, some of our group played nine holes at Skukuza Golf Club, a rough-but-charming course billed as the wildest in the world. Warthogs grazed the fairways. Any ball that landed near the hippo- or crocodile-infested water hazards was best considered lost.

Other offbeat diversions include wildlife hides, bush walks (available with a ranger), and photographic safaris. Just don’t expect luxury spas or boutique wine tastings. Kruger’s amenities are practical rather than performative.

When to go

Kruger is a year-round destination, but conditions vary by season. The dry winter months (May to October) are best for game viewing: animals cluster around waterholes, and vegetation is sparse. Temperatures are cooler, and there’s less risk of malaria.

The wet summer months (November to April) bring lush greenery, dramatic skies and excellent birdwatching, though some roads can become muddy, and sightings are more spread out.

Practical tips

• Flights: British Airways and Virgin Atlantic run daily services from London to Johannesburg. Airlink flies from Johannesburg to Skukuza Airport inside the park.

• Car Hire: Available from Avis and Europcar at Skukuza. Go for height and comfort — SUV or 4×4 — not speed.

• Costs: Expect to pay around €160/day for a large SUV in peak season.

• Accommodation: Prices vary, but a two-bedroom SANParks bungalow is typically under €80 per night. Book via www.sanparks.org. Private camp rates vary by lodge.

• Take a camera with a telephoto lens. We rented lenses from https://lensesforhire.co.uk

• Health & Safety: Kruger is a low-risk malaria zone. Crime is extremely rare. Stick to the rules — stay in your car, respect wildlife, and make it back to camp before sunset.

Professor Tim Coulson is Professor of Zoology at the University of Oxford, where he has led both the Zoology and Biology departments. He was previously at Imperial College London and has also held positions at Cambridge University and the Institute of Zoology London. A highly decorated scientist with awards from major institutions including the Royal Society, he has edited leading journals and served on Government advisory boards. His first book for general readers, “A Little History of Everything” (Penguin Michael Joseph), traces the 13.8-billion-year story from the Big Bang to human consciousness and is available to buy on Amazon.

READ MORE: ‘Meet Omar Yaghi, the Nobel Prize chemist turning air into water‘. From a childhood in a one-room home in Amman to chemistry’s highest honour, Omar Yaghi’s creation of metal–organic frameworks is reshaping how we draw water from the air and carbon from the atmosphere. The European’s Professor Tim Coulson and Professor Syma Khalid, both of the University of Oxford, spoke with him on their Science of the Times podcast.

Do you have news to share or expertise to contribute? The European welcomes insights from business leaders and sector specialists. Get in touch with our editorial team to find out more.

Photos: Alex Loh/Sonya Clegg/Tim Coulson

RECENT ARTICLES

-

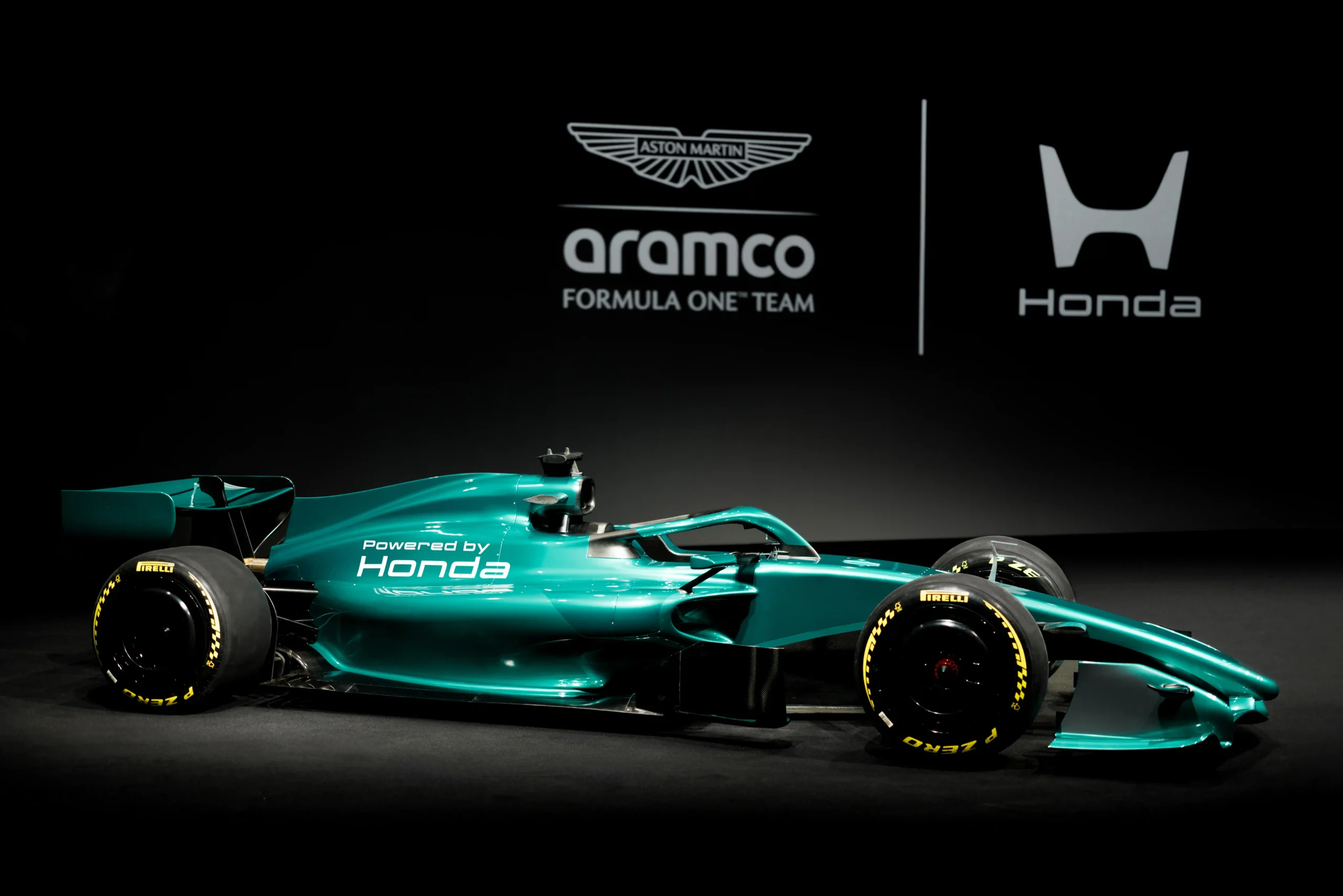

A new green dawn: inside Aston Martin’s turbulent start to Formula 1’s 2026 revolution

A new green dawn: inside Aston Martin’s turbulent start to Formula 1’s 2026 revolution -

WPSL targets £16m-plus in global sponsorship drive with five-year SGI partnership

WPSL targets £16m-plus in global sponsorship drive with five-year SGI partnership -

Need some downtime? Head to Nerja for some serious decompression

Need some downtime? Head to Nerja for some serious decompression -

How a book becomes a ‘bestseller' (and it’s not what you think)

How a book becomes a ‘bestseller' (and it’s not what you think) -

Fipronil: the silent killer in our waterways

Fipronil: the silent killer in our waterways -

Addiction remains misunderstood despite clear medical consensus

Addiction remains misunderstood despite clear medical consensus -

New guide to the NC500 calls time on 'tick-box tourism'

New guide to the NC500 calls time on 'tick-box tourism' -

Bon anniversaire, Rétromobile: Paris’ great motor show turns 50

Bon anniversaire, Rétromobile: Paris’ great motor show turns 50 -

Ski hard, rest harder: inside Europe’s new winter-wellness boom

Ski hard, rest harder: inside Europe’s new winter-wellness boom -

Baden-Baden: Europe’s capital of the art of living

Baden-Baden: Europe’s capital of the art of living -

Salzburg in 2026: celebrating 270 years of Mozart’s genius

Salzburg in 2026: celebrating 270 years of Mozart’s genius -

Sea Princess Nika – the ultimate expression of Adriatic elegance on Lošinj

Sea Princess Nika – the ultimate expression of Adriatic elegance on Lošinj -

Hotel Bellevue, Lošinj, Croatia – refined wellness by the Adriatic

Hotel Bellevue, Lošinj, Croatia – refined wellness by the Adriatic -

Padstow beyond Stein is a food lover’s dream

Padstow beyond Stein is a food lover’s dream -

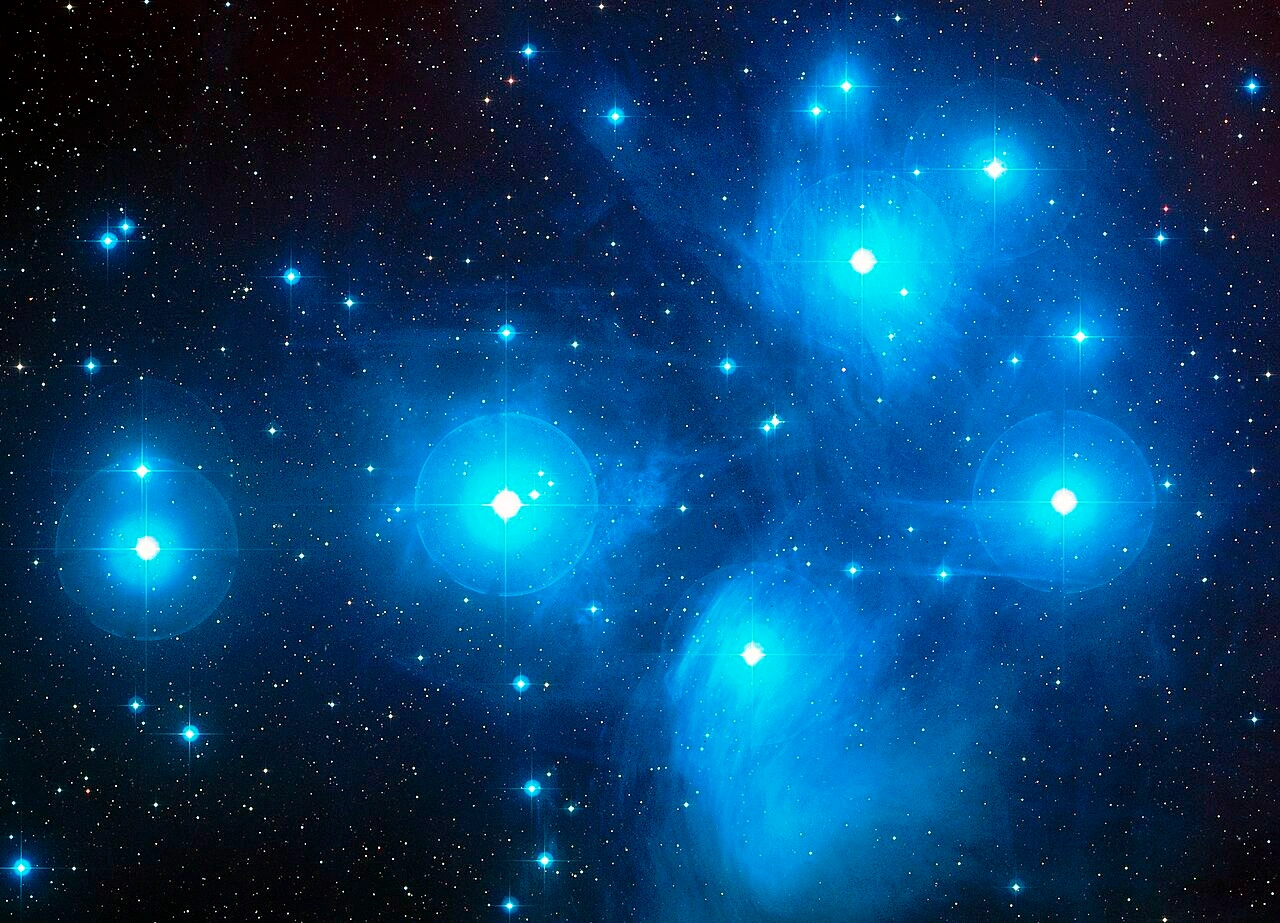

Love really is in the air. How to spot a sky full of heart-stealing stars this Valentine's Day

Love really is in the air. How to spot a sky full of heart-stealing stars this Valentine's Day -

Cora Cora Maldives – freedom, luxury and a celebration of island life

Cora Cora Maldives – freedom, luxury and a celebration of island life -

Hotel Ambasador: the place to stay in Split

Hotel Ambasador: the place to stay in Split -

Maslina Resort, Hvar – mindful luxury in the heart of the Adriatic

Maslina Resort, Hvar – mindful luxury in the heart of the Adriatic -

The bon hiver guide to Paris

The bon hiver guide to Paris -

Villa Mirasol – timeless luxury and discreet elegance on the island of Lošinj

Villa Mirasol – timeless luxury and discreet elegance on the island of Lošinj -

Lošinj’s Captain’s Villa Rouge sets a new standard in private luxury hospitality

Lošinj’s Captain’s Villa Rouge sets a new standard in private luxury hospitality -

Villa Nai 3.3: A Michelin-recognised haven on Dugi Otok

Villa Nai 3.3: A Michelin-recognised haven on Dugi Otok -

The European road test: The Jeep Wrangler Rubicon

The European road test: The Jeep Wrangler Rubicon -

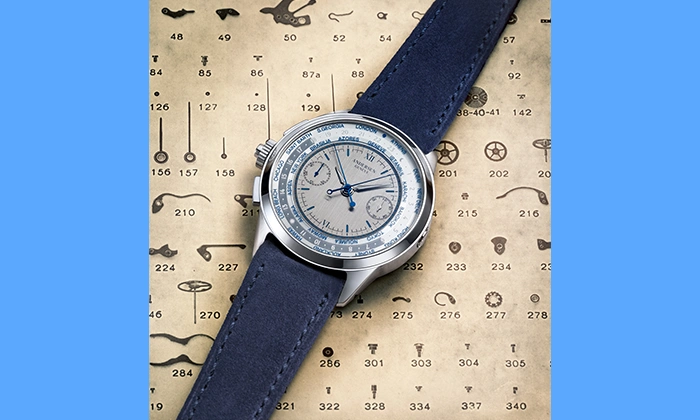

Rattrapante Mondiale – Split-Seconds Worldtimer

Rattrapante Mondiale – Split-Seconds Worldtimer -

Adaaran Select Meedhupparu & Prestige Water Villas: a Raa Atoll retreat

Adaaran Select Meedhupparu & Prestige Water Villas: a Raa Atoll retreat